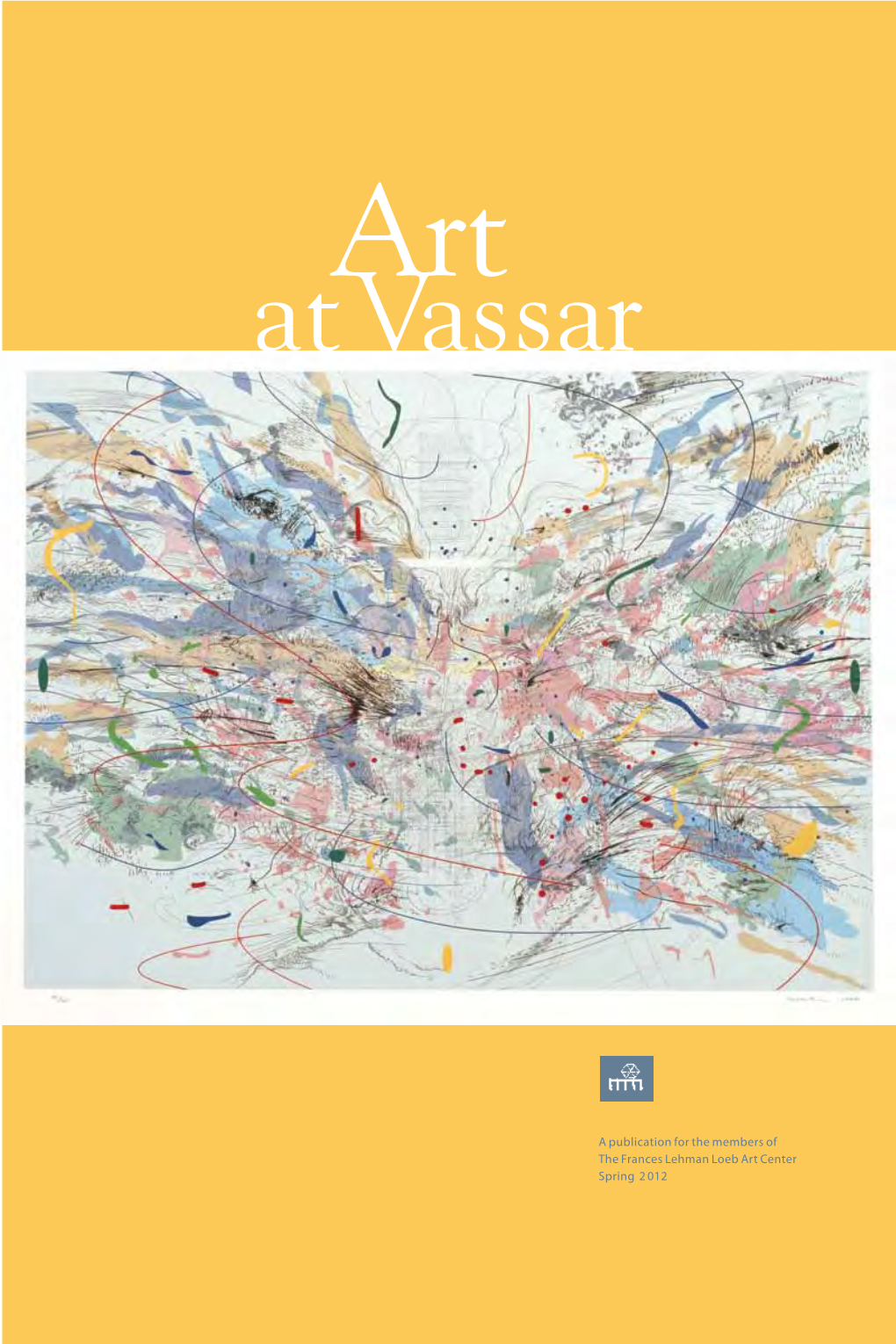

Art at Vassar, Spring 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Massimo Campigli - Biography

Culture and Arts: Bridges to Solidarity (CABS) Project Number: 2019-1-DE02-KA204-006113 Project Number: 2019-1-DE02-KA204-006113 Activity: Evolution of Arts in Europe – Massimo Campigli - Biography Author Volkshochschule Olching e.V. – Hélène Sajons Name: Massimo Campigli Born in Berlin/Germany under the name of Max Ihlenfeldt on July 4th, 1895 Died on the 31st of May 1971 (aged 75) in Saint- Tropez, France Nationality: Italian Profession: Painter and journalist Art Movement: Expressionism and Fauvism 1 Massimo Campigli was an Italian journalist and painter. He was born as Max Ihlenfeldt in Berlin but his mother moved to Florence where he spent his childhood. In 1909 they moved to Milan where Campigli started later to work for the “Letteratura magazine” as journalist. He used to frequent avant-garde circles and met Umberto Boccioni and Carlo Carrà who were leading figures of the Futurism movement in Italy. Deported to Hungary, Campigli was a prisoner of war from 1916–18. After the war (1919) he went to Paris where he was foreign correspondent for the “Corriere della Sera”. It was there that he started to paint and became in 1926 a member of the "Paris Italians", a group of artists including e.g. de Chirico, de Pisis, Renato Paresce, Savinio, Severini and Mario Tozzi. Frequent visits to Le Louvre deepened Campigli's interest in ancient Egyptian art, which became a lasting source of his own paintings. The Etruscan collection that he discovered at the National Etruscan Museum in Rome, had also an important influence on his art. In his first figurative works Campigli made use of geometrical designs to represent human figures; in these paintings the influence of Pablo Picasso and Fernand Léger is easily recognizable. -

Ode Info Sheet

Ode (World Premiere – 2019) Choreography: Jamar Roberts Rehearsal Associate: Marion-Skye Brooke Logan Music: Don Pullen Costume design: Jamar Roberts Lighting design: Brandon Stirling Baker Set design: Libby Stadstad A meditation on the beauty and fragility of life in a time of growing gun violence, Ode is the first in a series of three new dance works that company member Jamar Roberts is creating in his role as Ailey’s first-ever Resident Choreographer. Like his critically-acclaimed Members Don’t Get Weary (2017), this work for six dancers will feature a jazz score – Don Pullen’s “Suite (Sweet) Malcolm (Part 1 Memories and Gunshots)” – and Roberts’ own costume designs. “… a powerful and poetic exploration of the effects of gun violence…” Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in The New York Times Jamar Roberts’ Ode. Photo by Paul Kolnik. “’Ode’ feels like another revelation for Ailey. [Robert] Battle is smart to give Roberts a platform to develop… Works such as “Ode” constitute a powerful new direction for the company.” The Washington Post “It’s delicate, daring, and heartbreaking… says something hopeful about the present and future of this company. It now has a resident choreographer with talent and guts.” The New York Times Jamar Roberts Miami native Jamar Roberts graduated from the New World School of the Arts after beginning his studies at the Dance Empire of Miami, where he continues to teach and mentor students each year. He received a fellowship to The Ailey School before becoming a member of Ailey II, Complexions Contemporary Ballet and Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in 2002. -

Reggie Workman Working Man

APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM REGGIE WORKMAN WORKING MAN JIM JONNY RICHARD EDDIE McNEELY KING WYANDS JEFFERSON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JIM Mcneely 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JONNY KING 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : REGGIE WORKMAN 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : RICHARD WYANDS by marilyn lester Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest WE Forget : EDDIE JEFFERSON 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : MINUS ZERO by george grella US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviews 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne -

Rare Artists' Books with Etchings Lithographs and Pochoirs, Signed

Rare Artists’ Books with etchings lithographs and pochoirs, signed and limited editions, by: Braque, Chagall, Dali, Gauguin, Leger, Manet, Matisse, Miro’, Picasso, Renoir, and others Masters Etchings and Lithographs by: Chagall, Picasso, and Renoir. THE RED FINCH Reston Auction House is a new branch of the well- established MARNINART Rare Art Books & Modern and Contemporary Art. Since 2000 Marninart has operated on the market of rare books and contemporary art, accomplishing a worldwide clientele that includes Collectors, Museums, and Art Galleries. Marninart is recognized as one of the most specialized libraries for Illustrated Art Books of Picasso, Chagall, Matisse, and the Impressionists, and is a member of two prestigious worldwide bookseller’s associations specializing in rare books: ABAA Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America, and ILAB the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers. The latest trend for online art dealers and booksellers has evolved into online auctions, in order to reach a larger audience and visibility in the surreal internet world. Marninart is ready to begin this new adventure in the online auction market with great excitement and enthusiasm, presenting THE RED FINCH Reston Auction House as result of its expertise, knowledge and reliability. Visit Marninart @ www.marninart.net to learn more about us Our Goal is to provide the same dedicated costumer service, maintaining a real relationship with our clientele, buyers or consignors, in the wish of giving an enjoyable experience through our auction service. 1 Francis Bacon. Derriere le Miroir 162 - Francis Bacon Deluxe Edition. Michel Lereis, David Sylvester Maeght, Paris 1966 – Deluxe edition of Derriere le Miroir # 162 dedicated to Francis Bacon. -

Le Cas De Monsieur Sarmiento Et Les Artistes Italiens Résidant À Paris Dans Les Années Trente

Le cas de Monsieur Sarmiento et les artistes italiens résidant à Paris dans les années Trente. Plusieurs peintres italiens vivant à Paris en 1928 décident de former le groupe des « Italiens de Paris ». Ce groupe est composé d’artistes dont quelques-uns sont déjà reconnus dans le milieu culturel méditerranéen, entre le Futurisme et la Métaphysique : Giorgio de Chirico, Alberto Savinio, Gino Severini, Massimo Campigli, René Paresce, Mario Tozzi et Filippo de Pisis. Jusqu’en 1933, ils inaugureront plusieurs expositions ensemble. Au début, ce fut un groupe de petite taille sans chef de file, mais la plupart n’était que de passage. Bien que Giorgio de Chirico pouvait être l’unique à pouvoir créer une place aux artistes Italiens dans l’Ecole de Paris, son tempérament trop instable et lunatique ne pût le permettre. C’est en 1926 que Mario Tozzi fonde le « Groupe des sept » avec Severini, Campigli, de Pisis, Paresce, Savinio et de Chirico pour encourager une série de manifestations d’art italien à Paris. Quelques-uns sont déjà parisiens lorsque la Première Guerre Mondiale éclate. Plusieurs ont déjà trouvé leur consécration. Bien que Gino Severini quitte la capitale française en 1926, il envoie une série de tableaux pour l’exposition « Les italiens de Paris » organisée par Mario Tozzi en 1927, et participera également au « Salon des Indépendants ». Giorgio de Chirico de retour à Paris trouvera la gloire en participant à la naissance du Surréalisme en 1924, dont il est par ailleurs considéré comme étant l’un des pères fondateurs. Alberto Savinio, frère de Giorgio de Chirico, arrive à Paris en 1926 et avec le soutien de Jean Cocteau, il dévoilera ses talents de peintre. -

Italiani a Parigi

italiani a Parigi Da Severini a S a v i n i o Da De ChiriCo a CamPigli Birolli Boldini Bucci campigli de chirico de pisis levi magnelli m e n z i o m o d i g l i a n i p a r e s c e pirandello prampolini rossi savinio severini soffici Tozzi zandomeneghi ItalIanI a ParIgI D a S e v e r I n I a S AVI n IO Da De ChIrico a CaMPIGLI Bergamo, 10 - 30 maggio 2014 Palazzo Storico Credito Bergamasco Curatori Angelo Piazzoli Paola Silvia Ubiali Progetto grafico Drive Promotion Design Art Director Eleonora Valtolina Indicazioni cromatiche VERDE BLU ROSSO C100 M40 Y100 C100 M80 Y20 K40 C40 M100 Y100 PANTONE 349 PANTONE 281 PANTONE 187 R39 G105 B59 R32 G45 B80 R123 G45 B41 ItalIanI a ParIgI Da Severini a SAVINIO Da De Chirico a Campigli p r e C u r so r i e D e r e D i Opere da collezioni private Birolli, Boldini, Bucci Campigli, de Chirico de Pisis, Levi, Magnelli Menzio, Modigliani Paresce, Pirandello Prampolini, Rossi Savinio, Severini, Soffici Tozzi, Zandomeneghi 1 I g ri a P a P r e f a z I o n e SaggIo CrItICo I a n li a T I 2 P r e f a z I o n e SaggIo CrItICo 3 Italiani a Parigi: una scoperta affascinante Nelle ricognizioni compiute tra le raccolte private non abbiamo incluso invece chi si mosse dall’Italia del territorio, nell’intento di reperire le opere che soltanto per soggiorni turistici o per brevi comparse. -

Les Italiens De Paris

GRAPEVINE November 2015 - 7 Les Italiens de Paris etween 1928 and 1933, a group of seven Italian artists lived and worked in Paris: Giorgio de Chirico, his brother Andrea de Chirico (who took the name Alberto Savinio), Massimo Campigli, Filippo De Pisis, René Paresce, Gino Severini and Mario Tozzi. They followed on the footsteps of Amedeo Modigliani (also Italian), who lived Band worked in Paris from 1906 until his death. These artists developed new concepts of art, distancing themselves from Futurism and re-affirming the importance of the Italian tradition, while at the same time establishing themselves firmly in the here and now. Much of their work is an homage to classicism but re-visited often in a disturbing, surrealistic or metaphysical way. The Lucca Center for Contemporary Art has brought some of these fascinating paintings to Lucca where they are now on display. Le muse inquietanti by Giorgio de Chirico depicts two classical statues with eyeless sartorial Giorgio de Chirico mannequins for heads, situated in the foreground of a broad, grimly-lit piazza with the Estense Le Muse Inquietanti, 1950 ca. Castle of Ferrara in the distance, alongside a factory. olio su tela, 97x66 cm Both Giorgio and his brother were born in Greece, and the classical tradition figures strongly in their Fondazione Carima art, but this is transformed by the historical context in which they lived, between the two world wars. – Museo Palazzo Ricci, Macerata Photo © Stefano Ciocchetti Le navire perdu by Alberto Savinio offers the colorful and playful vision of a ship filled with toys, but which has hit the reefs while an ominous grey sky hovers in the background. -

Italian Painting in Between the Wars at MAC USP

MODERNIDADE LATINA Os Italianos e os Centros do Modernismo Latino-americano Classicism, Realism, Avant-Garde: Italian Painting In Between The Wars At MAC USP Ana Gonçalves Magalhães This paper is an extended version of that1 presented during the seminar in April 2013 and aims to reevaluate certain points considered fundamental to the research conducted up to the moment on the highly significant collection of Italian painting from the 1920s/40s at MAC USP. First of all, we shall search to contextualize the relations between Italy and Brazil during the modernist period. Secondly, we will reassess the place Italian modern art occupied on the interna- tional scene between the wars and immediately after the World War II —when the collection in question was formed. Lastly, we will reconsider the works assem- bled by São Paulo’s first museum of modern art (which now belong to MAC USP). With this research we have taken up anew a front begun by the museum’s first director, Walter Zanini, who went on to publish the first systematic study on Brazilian art during the 1930s and 40s, in which he sought to draw out this relationship with the Italian artistic milieu. His book, published in 1993, came out at a time when Brazilian art historiography was in the middle of some important studies on modernism in Brazil and its relationship with the Italian artistic milieu, works such as Annateresa Fabris’ 1994 Futurismo Paulista, on how Futurism was received in Brazil, and Tadeu Chiarelli’s first articles on the relationship between the Italian Novecento and the São Paulo painters. -

Export / Import: the Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2016 Export / Import: The Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969 Raffaele Bedarida Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/736 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by RAFFAELE BEDARIDA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 RAFFAELE BEDARIDA All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Emily Braun Chair of Examining Committee ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Rachel Kousser Executive Officer ________________________________ Professor Romy Golan ________________________________ Professor Antonella Pelizzari ________________________________ Professor Lucia Re THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by Raffaele Bedarida Advisor: Professor Emily Braun Export / Import examines the exportation of contemporary Italian art to the United States from 1935 to 1969 and how it refashioned Italian national identity in the process. -

Alberto Savinio and the "Years of Consent:" the Experience of "Colonna" (1933–34)

ITALIAN MODERN ART | ISSUE 2: Alberto Savinio ISSN 2640-8511 and the “Years of Consent:” The Experience of “Colonna” (1933–34) ALBERTO SAVINIO AND THE "YEARS OF CONSENT:" THE EXPERIENCE OF "COLONNA" (1933–34) italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/alberto-savinio-and-the-years-of-consent-the-experience- 0 of-colonna-1933-34 Lucilla Lijoi Alberto Savinio, Issue 2, July 2019 https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/alberto-savinio/----------------. - ---- Abstract This presentation considers the significant role Alberto Savinio played in the production and promotion of Italian culture during the early thirties, focusing specifically on Savinio’s founding and directing of the monthly review Colonna. Periodico di civiltà italiana. Although Colonna folded after only five issues, during its run the periodical served as a vehicle for Savinio to actively contribute to the revival of Italian culture as well as the movement around the “uomo nuovo italiano,” which was promoted by Fascism in the so-called “years of consent.” Crucial to confronting the delicate relationship of Alberto Savinio to fascism in the early thirties is the consideration of his decision to establish Colonna (figure 1), a monthly journal of art and culture that was partially in line with the cultural direction being promoted by Benito Mussolini. An important date in this history is 1933, the year in which Savinio moved to Italy with his family after several years in Paris. The Italy of the early thirties was very different from the country Savinio had left in 1926. In fact, Mussolini was pursuing the total “renovation” of the Italian people in his attempt to create “the new fascist man,” a protagonist for both the Mediterranean and Europe. -

Open Windows 10

Leticia de Cos Martín Martín Cos de Leticia Beckmann Beckmann Frau than Quappi, much more more much Quappi, pages 47 — 64 47 — 64 pages Clara Marcellán Marcellán Clara in California in California Kandinsky and Klee Klee and Kandinsky of Feininger, Jawlensky, Jawlensky, of Feininger, and the promotion promotion the and Galka Scheyer Galka Scheyer ‘The Blue Four’: Four’: Blue ‘The pages 34 — 46 34 — 46 pages Manzanares Manzanares Juan Ángel Lpez- Ángel Juan ~' of modern art as a collector as a collector Bornemisza’s beginnings beginnings Bornemisza’s - ~~.·;•\ Thyssen Baron On ~ .. ;,~I il~ ' r• , ~.~ ··v,,,:~ ' . -1'\~J"JJj'-': . ·'-. ·•\.·~-~ . 13 — 33 pages Nadine Engel Engel Nadine Expressionist Collection Collection Expressionist Thyssen-Bornemisza’s German German Thyssen-Bornemisza’s Beginning of Hans Heinrich Heinrich Hans of Beginning 1, 1 ~- .,.... Museum Folkwang and the the and Folkwang Museum ,..~I,.. '' i·, '' ·' ' ' .·1,.~.... Resonance Chamber. Chamber. Resonance . ~I•.,Ji'•~-., ~. pages 2 — 12 2 — 12 pages ~ -~~- . ., ,.d' .. Ali. .~ .. December 2020 2020 December 10 10 Open Windows Windows Open Open Windows 10 Resonance Chamber. Museum Folkwang and the Beginning of Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza’s German Expressionist Collection Nadine Engel Emil Nolde Young Couple, c. 1931–35 22 HollandischerDirektor bracht ✓ Thyssen-Schatzenach Essen Elnen kaum zu bezifiernden Wert bat elne Ausslellung des Folkwang-Museums, die btszum 20. Marz gezelgt wird: sie ent hiilt hundertzehn Melsterwerke der europaisdlen Malerei des 14. bis 18. Jahrhunderts aus der beriihmten Sammlung Sdtlo8 Roboncz, die heute Im Besitz des nodt Jungen Barons H. H. Thys sen-Bornemisza ist und in der Villa Favorlta bei Lugano ihr r Domlzil hat. Insgesamt mnfafll sie 350 Arbeiten. -

Jazz Collection: George Adams

Jazz Collection: George Adams Dienstag, 29. April 2014, 21.00 - 22.00 Uhr Samstag, 03. Mai 2014, 22.00 - 24.00 Uhr (Zweitsendung) Seine Improvisationen sind expressiv und explosiv, dann wieder spielt er fast wie im Swingzeitalter - und seine Stücke sind äusserst melodiös. In George Adams versöhnen sich die Gegensätze wie im Märchen Fuchs und Hase. Sein Sound war ebenso körperlich wie sein ganzes Spiel, dazu seine nach hinten geneigte Postur, die Augen, von denen man oft nur das Weisse sah: George Adams spielte das Saxophon so kraftvoll und bestimmt, dass ihm auch die Lehrjahre in der Band des unberechenbaren Charles Mingus nichts anhaben konnten. Im Gegenteil: Sie kanalisierten seine Kräfte und brachten sie so sehr auf den Punkt, dass er mit seiner eigenen Band erfolgreich viele Platten einspielen und auch noch auftreten konnte, als er den Kampf gegen den Krebs im Grunde schon verloren hatte. Schon als Teenager weggeblasen von George Adams Saxophonspiel und -sound wurde der Zürcher Saxophonist Omri Ziegele – er ist Gast von Jodok Hess. Redaktion: Jodok Hess George Adams: Paradise Space Shuttle ( 1978) CD Timeless Records Track 1: Intentions Charles Mingus: Mingus Moves (1973) CD Atlantic Track 2: Opus 4 George Adams: Melodic Excursions (1982) CD Timeless Track 2: God Has Smiled On Me George Adams-Don Pullen Quartet: City Gates (1983) CD Timeless Track 5: City Gates Phalanx: Got Something Good For You (1985) CD Moers Music Track 4: A Night Out Track 1: Upside Down Phalanx: In Touch (1988) CD DIW Track 5: Look ans See Bonustracks – nur in der Samstagsausgabe George Adams: Paradise Space Shuttle ( 1978) CD Timeless Records Track 3 : Send In The Clowns Gil Evans & The Monday Night Orchestra: Live at Sweet Basil CD Gramavision Track 3: Orange Was the Color of Her Dress George Adams / Don Pullen: Decisions CD Timeless Records Track 1: Trees and Grass and Thangs Phalanx : Original Phalanx CD DIW Track 7: Playground Charles Mingus Orchestra: Charles Mingus.