The Inheritance of Black, Yellow and Tortoiseshell Coat-Colour in Cats Is Both Complicated and Interesting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abyssinian Cat Club Type: Breed

Abyssinian Cat Association Abyssinian Cat Club Asian Cat Association Type: Breed - Abyssinian Type: Breed – Abyssinian Type: Breed – Asian LH, Asian SH www.abycatassociation.co.uk www.abyssiniancatclub.com http://acacats.co.uk/ Asian Group Cat Society Australian Mist Cat Association Australian Mist Cat Society Type: Breed – Asian LH, Type: Breed – Australian Mist Type: Breed – Australian Mist Asian SH www.australianmistcatassociation.co.uk www.australianmistcats.co.uk www.asiangroupcatsociety.co.uk Aztec & Ocicat Society Balinese & Siamese Cat Club Balinese Cat Society Type: Breed – Aztec, Ocicat Type: Breed – Balinese, Siamese Type: Breed – Balinese www.ocicat-classics.club www.balinesecatsociety.co.uk Bedford & District Cat Club Bengal Cat Association Bengal Cat Club Type: Area Type: PROVISIONAL Breed – Type: Breed – Bengal Bengal www.thebengalcatclub.com www.bedfordanddistrictcatclub.com www.bengalcatassociation.co.uk Birman Cat Club Black & White Cat Club Blue Persian Cat Society Type: Breed – Birman Type: Breed – British SH, Manx, Persian Type: Breed – Persian www.birmancatclub.co.uk www.theblackandwhitecatclub.org www.bluepersiancatsociety.co.uk Blue Pointed Siamese Cat Club Bombay & Asian Cats Breed Club Bristol & District Cat Club Type: Breed – Siamese Type: Breed – Asian LH, Type: Area www.bpscc.org.uk Asian SH www.bristol-catclub.co.uk www.bombayandasiancatsbreedclub.org British Shorthair Cat Club Bucks, Oxon & Berks Cat Burmese Cat Association Type: Breed – British SH, Society Type: Breed – Burmese Manx Type: Area www.burmesecatassociation.org -

November 2020 Newsletter

November SEASONS GREETINGS FROM TEN LIVES CLUB! 2020 Dear Friends of Ten Lives Club, Throughout this whirlwind of a year, you made amazing things happen. You made sure that over 2,000 cats, who had nowhere else to go, got the chance at life that they deserved. It is said that cats have “nine lives”. Ten Lives Club makes sure they have ten lives…their forever and final home when they leave our shelter. Whether entering our program through a hoarding case or brought to us because their families could no longer care for them, you made sure these cats had somewhere they could turn to. When most other shelters closed during the pandemic we stayed open to help and you made that possible. When we had to cancel most annual fundraising events, you stepped up financially to help. Without you, cats would not be able to receive the extra time and resources they need to learn to trust again. Thanks to you, cats who were left abandoned and starving received immediate care. Cats that were sick were healed with the proper attention and medical treatments. Innocent animals on death-row at kill-shelters were gladly taken in. Kittens just days old received individual care in foster homes. You make our mission and work possible. Your support ensures that we can provide the very best care for each cat who is brought to our shelter. You save lives. You, our community, are the reason our organization is so successful and has grown to be the unbelievable shelter we have become over the almost twenty years in existence. -

A Journey to Home: Quinn’S Story Impact by the Numbers Quinn, a Beautiful Tortoiseshell Cat, Or “Tortie”, Is the Picture Purr-Fect Example of a Rescue Success Story

Together, we are making sure making sure are we Together, they ALL journey HOME they A Journey There is no doubt that our theme this year was 2020 has been a year of significant change at The Bangor Maine 04401 Bangor, 693 Mount Hope Ave. ‘overcoming challenges’. From construction to Humane Society. We saw the successful conclusion of our Capital quarantine, our staff, our dedicated volunteers, and Campaign and the completion of the much-needed renovations to Home you, our loyal and generous donors, tenaciously to our building. For years to come, these changes will benefit the adapted to an ever-shifting landscape. thousands of animals that pass through our doors looking for their In the face of these changes, we lived and forever homes. breathed our mission to champion humane treatment and adoption A phrase that has been used a lot in the past 9 months is “We are of companion animals. Together, and during a time defined by the all in this together”. This feeling has been one that I have always importance of home, we improved outcomes, finding homes for 98% felt as a supporter of the Bangor Humane Society. Everything we of pets that came through our doors; prioritizing specialized care; and go through, we go through with the help of the offering programming to help our friends and neighbors keep their communities we serve. Donors, volunteers, and beloved pets where they belong--with family. staff work together to make sure that our mission When I think of the dedication and flexibility put forth by our of helping all animals can be carried out. -

Norwegian Forest Cat

Norwegian Forest Cat solid and bicolor cats. Type and quality of coat is of primary Norwegian Forest Cat importance; color and pattern are secondary. POINT SCORE PATTERNS: every color and pattern is allowable with the excep- tion of those showing hybridization resulting in the colors choco- HEAD (50) late, sable, lavender, lilac, cinnamon, fawn, point-restricted Nose profile............................................................................. 10 (Himalayan type markings), or these colors with white. Muzzle..................................................................................... 10 Ears......................................................................................... 10 COLORS AND PATTERN: the color and pattern should be clear Eye shape ................................................................................ 5 and distinct. In the case of the classic, mackerel and spotted tab- Eye set ..................................................................................... 5 bies the pattern should be well-marked and even. Neck......................................................................................... 5 DISQUALIFY: severe break in nose, square muzzle, whisker Chin.......................................................................................... 5 pinch, long rectangular body, cobby body, incorrect number of BODY (30) toes, crossed eyes, kinked or abnormal tail, delicate bone struc- Torso....................................................................................... 10 ture, malocclusion -

Inheritance of Coat-Color in Cats

AUTHOR'S .4B$TRACT OF THIS PAPER ISSOED BY THE BIBLIOGRAPIIIC! SERVICE, FEBXUAXY 16 INHERITANCE OF COAT-COLOR IN CATS P. W. WHITING Zoological Laboratory of the University of Pennsylvania TWO PLATES CONTENTS I. Introduction: The color-factors of domestic cats.. .......... 539 11. Presentation and discussion of data.. ................................. 541 .4. Maltese dilution.. ............................................... 541 B. White and white-spotting. C. Solid yellow and yellow-sp D. Siamese dilution.. ........ E. Banding and ticking.. ............. a. Statement of factorial diffcren acters ..................................................... 550 h. Experimental data c. The number of loc d. Physiology of color-production.. 111. The origin of color varieties of the cat.. .... IV. Summary.. ........... V. Literature cited.. .................................................... 564 I. INTRODUC'I'IOS: THE COLOIt FACTORS OF DOMESTIC CATS In a series of experiments begun at the University of Penn- sylvania in the autumn of 1914 and extending up to the present time, the inheritance of coat-color in cats has been investigated. Although the number of litters obtained has not been large, it has been found possible to determine several points in regard to the mechanism of heredity by means of critical crosses. This has been largely due to the fact that the characters studied seg- regate for the most part cleanly from each other so that it has been easy to classify the animals. My thanks are due to Dr. McClung and to Dr. Colton for the kindly interest which they have taken in the work and to the 539 540 P. W. WHITING University of Pennsylvania for the expense of the experiments. I also wish to thank the Zoological Society of Philadelphia for the opportunity of crossing my cats with the Caffre cat. -

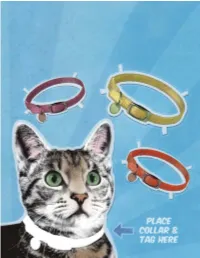

COLLARS and SENSE Stray and Lost Cats Fill Shelters (But a Movement to Identify Kitties Could Stem the Tide)

COLLARS AND SENSE Stray and lost cats fill shelters (but a movement to identify kitties could stem the tide) BY ARNA COHEN Echoing in the classifieds and online postings of desper- Johnson, front office supervisor at the Sacramento SPCA in ate people in search of their loved ones is a sad refrain of California. “... None had collars.” remorse: Compare that with the shelter’s much higher reunion Lost: Small shorthair tortoiseshell cat… no collar. rate for stray dogs—almost 580 out of about 1,700—and Found: Siamese, very friendly, wants to be indoors the situation for cats looks particularly bleak. And that’s just badly… no collar. one shelter in one state. At a time when the homeless cat Lost: Ragdoll, looks like long-haired Siamese, blue population is at crisis levels nationwide, only 2 to 5 percent eyes… no collar. of the millions entering shelters each year are reunited with Found: Female tortoiseshell, hungry, crying, very their families. For dogs, the figure can be eight times as sweet… no collar. high. The endless recitation of regrettable omissions and last- The statistics mirror the disparities between the pres- ditch hopes reveals the one thing that most often foils the ence of visible identification on dogs versus cats: One recent reunion of a stray cat and his family—the absence of a sim- study found that only 14 percent of lost cats were wearing ple collar and ID tag that could serve as his ticket home. any ID, compared with 43 percent of dogs. The oversight may seem minor in the case of a single “If every pet cat in the country had a collar and tag, cat and a single owner. -

Adopt Rescue Donate Foster Volunteer

Adopt ♥ Rescue ♥ Donate ♥ Foster ♥ Volunteer August 2019 Priceless TM Expanding Families One Pet at a Time PawPrints Magazine's Homeless Cover Models Photo by: Michael Cline Photography Hi, everyone! I’m Poppy, a Walker Hound puppy, and this is my feline friend, Cleo. We’re inviting you to the 14th Annual Wilmington Fur Ball! This joyful and fun evening benefits rescue animals (like us) from New Hanover, Brunswick and Pender Counties. You’ll come together with other animal lovers while enjoying lavish hors d’oeuvres, wine, beer, champagne, a live band, and the opportunity to bid on many live and silent auction items. The event will be held on August 24, 2019, from 6:30 pm to 10:30 pm at The Terraces on Sir Tyler. The theme will be “The Roaring Twenties Speakeasy.” Tickets are $100 each and are available online at www.wilmingtonfurball.com. So dust off your dancing shoes and prepare for a night of great entertainment. It’s an event you won’t want to miss! Please see the ad on page 27. Cleo and I got all glammed up for our cover shoot, but normally we’re quite casual at Pender Humane Society, which is where we’re living while waiting for a home. I’m a 6-month-old boy and every bone in my body is sweet, sweet, sweet! I never meet a stranger and I love to get attention. I play well with other dogs and am neutered, vaccinated and microchipped. Am I the puppy you’re searching for? As for Cleo, she’s a 3-year-old Seal Point Siamese mix girl. -

The First Case of 38,XX (SRY-Positive) Disorder of Sex Development in A

Szczerbal et al. Molecular Cytogenetics (2015) 8:22 DOI 10.1186/s13039-015-0128-5 CASE REPORT Open Access The first case of 38,XX (SRY-positive) disorder of sex development in a cat Izabela Szczerbal1, Monika Stachowiak1, Stanislaw Dzimira2, Krystyna Sliwa3 and Marek Switonski1* Abstract Background: SRY-positive XX testicular disorder of sex development (DSD) caused by X;Y translocations was not yet reported in domestic animals. In humans it is rarely diagnosed and a majority of clinical features resemble thosewhicharetypicalforKlinefeltersyndrome(KS).HerewedescribethefirstcaseofSRY-positive XX DSD in a tortoiseshell cat with a rudimentary penis and a lack of scrotum. Results: Molecular analysis showed the presence of two Y-linked genes (SRY and ZFY)andanormalsequenceofthe SRY gene. Application of classical cytogenetic techniques revealed two X chromosomes (38,XX), but further FISH studies with the use of the whole X chromosome painting probe and BAC probes specific to the Yp chromosome facilitated identification of Xp;Yp translocation. The SRY gene was localised at a distal position of Xp. The karyotype of the studied case was described as: 38,XX.ish der(X)t(X;Y)(p22;p12)(SRY+). Moreover, the X inactivation status assessed by a sequential R-banding and FISH with the SRY-specific probe showed a random inactivation of the derivative XSRY chromosome. Conclusions: Our study showed that among DSD tortoiseshell cats, apart from XXY trisomy and XX/XY chimerism, also SRY-positive XX cases may occur. It is hypothesized that the extremely rare occurrence of this abnormality in domestic animals, when compared with humans, may be associated with a different organisation of the Yp arm in these species. -

Lost, Stolen, Surrendered and Sold How Pets Land in Labs

A PUBLICATION OF THE AMERICAN ANTI-VIVISECTION SOCIETY 2013 | Number 1-3 magazine AVLOST, STOLEN, SURRENDERED AND SOld HOW PETS LAND IN LABS +Animal Dealers ROOTS IN THE 19TH CENTURY pg 4 POUND SEIZURE PROFILES pg 8 2013 Number 1—3 HOW PETS LAND IN LAbs Lost, Stolen, Surrendered & Sold FEATURES 4 ANIMAL DEALERS: 4 ROOTS in THE 19TH CenTURY Archaic and corrupt, random source Class B dealers typify an antiquated science. With their dwindling numbers, these animal dealers are destined to be obsolete. By Crystal Schaeffer 8 Pound Seizure Profiles Personal stories of tragedy and triumph. 10 Research Faces the Facts The animal research community acknowledges that biomedical research will not be impeded if random source Class B dealers are put out of business. 2 By Sue Leary 12 Random Source Class B Dealers: A Sordid History of Dirty Dealings DEPARTMENTS Profiting from animal suffering, these animal brokers have rightly earned their 1 First Word dubious reputation. Calling for an end to random source By Vicki Katrinak Class B dealers. 15 Class B Dealers Selling Innocent Lives 2 Briefly Speaking Charting the business of Class B dealers. AAVS Supports Petitions to Protect By Vicki Katrinak Chimps; EU Bans Cosmetics Tested on Animals; Nearly 2 Million Urge FDA to 16 Ban on Pound Seizure Stop Sale of GE Salmon; United and Air A grassroots look at efforts to end the sale of shelter animals to research. Canada Say No to Primate Research; By Amy Draeger, Allie Phillips, and Crystal Schaeffer Animalearn Honors Humane Students. 9 Giving 18 Interview Profile: Stephanie Shain Confront cruelty by supporting humane Chief Operating Officer, Washington Humane Society science education. -

SABCCI Schedule

CORK CAT CLUB TH 36 Championship Show *************************************************** (Held under rules of Governing Council of the Cat Fancy of Ireland) To be held on SUNDAY 17TH SEPTEMBER 2017 at Scoil Mhuire Gan Smal, 1 Old Blarney Rd, Shean Lower, Blarney, Co. Cork Pedigree Judges Mrs Janet Green (England) FIFE Mr P Collin (England) GCCF Mme Veronique Sangin (France) LOOF Non Pedigree Judge Ms M Lenihan & Ms. E. Callan SHOW MANAGER ASSISTANT SHOW MANAGER Miss M Baker Mr C Noonan Arbutus 26 Elderwood Avenue Carrigloe Boreenmanna Road Cobh Co Cork Cork Tel: 00353 21 3811773 Tel: 086 8588821 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] CLOSING DATE FOR ENTRIES IS 23rd AUGUST 2017 This date must be strictly adhered to as the catalogue is being prepared in UK. Entries with correct fees should be sent to Show Manager Miss M Baker, address as above 1 Committee Mr C Noonan (Chairperson), Mrs. P Starkey (Vice-Chair), Ms C McCarthy (Secretary), Mrs L Anderson (Treasurer), Ms M Baker, Mrs R Murphy, Mr J Neligan, Mr D Hickey (Logistics Manager), Mrs M McSweeney, Mrs G Bowles, Mrs L Gash Hickey, Mr C Collins, Mrs L Buckley ************************************* Honorary Veterinary Surgeons Ms Clare Meade MVB, MRCVS, The Cat Hospital, Glanmire, Co. Cork. Mr. Richard Healy, MVB, MRCVS, Westside Vet Clinic, Model Farm Road, Cork Show Manager: Ms Margaret Baker, Arbutus, Carrigloe, Cobh, Co Cork Asst Show Manager: Mr Colm Noonan, 26 Elderwood Ave, Boreenmanna Rd, Cork GENERAL INFORMATION Registrations, transfers etc should be put in order AT ONCE, if you have not already done so. -

New Animal Shelter Will Touch the Lives of Thousands of Pets and Their People Page 3

“Uniting Pets and People Since 1947” March 2015 New animal shelter will touch the lives of thousands of pets and their people page 3 Inside this issue Bow Wow Boogie 7 Year in Review 8 Memorial Gifts 10 All in a Day’s Work 12 Happy Tails 13 Contact Us THE PAW PRINT POST BOARD OF DIRECTORS John Gessner, Vice President Anna Marie Ohler, Secretary A Home for Marleigh Audra Caplan Pete Hicks Dr. Andrew Holloway arleigh is a 3½-year-old female Hound Claudia Holman M mix who was surrendered to The Hu- Dr. Amy Hubbard mane Society of Harford County on March Elliot Kleinman Lawrence Kreis, Jr. 11, 2014 because of her separation anxiety Mary Leavens issues. Her prior family said that other than Stephen Nolan the separation anxiety, she was the perfect Dr. Robert Silcox Andrew Tress dog, but recently she had destroyed some mer volunteer & outreach coordinator, Nicky Linda Walls furniture and they could no longer keep her. Wetzelberger. Nicky owns a young outgoing Charles R. Wellington When she arrived at our shelter, Marleigh Australian Shepherd named Darra, who EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR was beyond terrified. Our shelter quickly bonded with Marleigh and Mary Leavens technicians were able to examine drew her out of her shell. It was SHELTER MANAGER her, but for days, she laid in her amazing to watch the transfor- Blaine Lang kennel, barely eating, not making mation! Outside in our play yard, ADMINISTRATION STAFF eye contact, and not responding to Marleigh and Darra would run, Becky Archer, Volunteer & touch or affection. She was reluc- romp and wrestle with each other. -

Standards 05-06

$9.00 SHOW STANDARDS MAY 1, 2019 - APRIL 30, 2020 THE CAT FANCIERS’ ASSOCIATION, INC.® PREFACE What is a standard? It is not a cat. A standard is an abstract aesthetic ideal. The realization of a good standard would result in a work of art or, at the very least, an object possessing artistic unity. Artistic unity requires that individual parts be in harmony with one another; that they possess balance and proportion; that together they enhance each other and strengthen the whole. A good work of art has its own inner logic. There is a feeling of inevitability and rightness about each detail. With a standard we aim at some satisfying visual shape that possesses a certain style. Style, too, implies an inner harmony and consisten- cy between the parts. In the realm of aesthetics, the whole is really greater than the sum of its parts, but each part enhances or detracts from the whole. Its realization should possess aesthetic and artistic validity. Nothing grotesque or distorted or ugly is implicit in the standard. Why then do some winning cats look ugly or distorted? Because they violate in some way the basic concept. A cat can have individual “good” features, and yet not fulfill the ideal of the standard. In a poor or amateurish work of art, some parts clash or can not be harmonized with other parts. There can be much brilliance coupled with abysmal weakness. Artistic unity is impaired or absent. If one analyzes any cat that appears “ugly,” one will discover that some feature or combination of features does not blend in well, or abruptly interferes, with the basic overall pattern of lines and planes.