The Unlearning Organisation: Cultural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KARLA BLACK Born 1972 in Alexandria, Scotland Lives And

KARLA BLACK Born 1972 in Alexandria, Scotland Lives and works in Glasgow Education 2002-2004 Master of Fine Art, Glasgow School of Art 1999-2000 Master of Philosophy (Art in Organisational Contexts), Glasgow School of Art 1995-1999 BA (Hons) Fine Art, Sculpture, Glasgow School of Art Solo Exhibitions 2021 Karla Black: Sculptures 2000 - 2020, FruitMarket Gallery, Edinburgh 2020 Karla Black: 20 Years, Des Moines Art Centre, Des Moines 2019 Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne 2018 The Power Plant, Toronto Karla Black / Luke Fowler, Capitain Petzel, Berlin 2017 Stuart Shave / Modern Art, London Festival d’AutoMne, Musée des Archives Nationales and École des Beaux-Arts, Paris MuseuM Dhondt-Dhaenens, Deurle 2016 Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milan A New Order (with Kishio Suga), Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh David Zwirner, New York Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne 2015 Irish MuseuM of Modern Art, Dublin 2014 Stuart Shave / Modern Art, London Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milan David Zwirner, New York 2013 Kestner Gesellschaft, Hannover Institute of ConteMporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne GeMeenteMuseuM, The Hague 2012 Concentrations 55, Dallas MuseuM of Art, Dallas Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin Gallery of Modern Art, Glasgow Stuart Shave / Modern Art, London 2011 Scotland + Venice 2011 (curated by The FruitMarket Gallery), Palazzo Pisani, 54th Venice Biennale, Venice 2010 Capitain Petzel, Berlin WittMann Collection, Ingolstadt -

'The Neo-Avant-Garde in Modern Scottish Art, And

‘THE NEO-AVANT-GARDE IN MODERN SCOTTISH ART, AND WHY IT MATTERS.’ CRAIG RICHARDSON DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (BY PUBLISHED WORK) THE SCHOOL OF FINE ART, THE GLASGOW SCHOOL OF ART 2017 1 ‘THE NEO-AVANT-GARDE IN MODERN SCOTTISH ART, AND WHY IT MATTERS.’ Abstract. The submitted publications are concerned with the historicisation of late-modern Scottish visual art. The underpinning research draws upon archives and site visits, the development of Scottish art chronologies in extant publications and exhibitions, and builds on research which bridges academic and professional fields, including Oliver 1979, Hartley 1989, Patrizio 1999, and Lowndes 2003. However, the methodology recognises the limits of available knowledge of this period in this national field. Some of the submitted publications are centred on major works and exhibitions excised from earlier work in Gage 1977, and Macmillan 1994. This new research is discussed in a new iteration, Scottish art since 1960, and in eight other publications. The primary objective is the critical recovery of little-known artworks which were formed in Scotland or by Scottish artists and which formed a significant period in Scottish art’s development, with legacies and implications for contemporary Scottish art and artists. This further serves as an analysis of critical practices and discourses in late-modern Scottish art and culture. The central contention is that a Scottish neo-avant-garde, particularly from the 1970s, is missing from the literature of post-war Scottish art. This was due to a lack of advocacy, which continues, and a dispersal of knowledge. Therefore, while the publications share with extant publications a consideration of important themes such as landscape, it reprioritises these through a problematisation of the art object. -

Download Press Release

LUCY SKAER CAROL RHODES HANNELINE VISNES HEAVY WEATHER May 18 – July 13, 2019 Opening Saturday May 18th Frans Halsstraat 26 From 6pm until 8pm GRIMM is proud to present Heavy Weather, an exhibition showers’ and ‘Violent Thunder’. These works function as an organised by Lucy Skaer (UK, 1975) with selected works by exploration of the role of feeling, emotion and subjectivity in Carol Rhodes (UK, 1959-2018) and Hanneline Visnes (NO, how we experience history, objects, images, or situations, 1972). The works in the show are united by the theme of despite degrees of abstraction or transmutation. temporality and landscape, meditating on nature, how it is altered and effected by human vision and action. This is In the paintings of Hanneline Visnes, which surround Skaer’s Skaer’s second exhibition with the gallery in Amsterdam La Chasse, stylised motifs of animals and plants are used to and follows her recent collaborative exhibition The Green comment on the representation and control of nature. Visnes Man held at the Talbot Rice Gallery in Edinburgh (UK). merges disparate patterns, motifs, and subjects into her meticulously crafted paintings. She explores and harnesses Lucy Skaer’s main body of work in the exhibition is titled the power of colour, utilising complementary hues that bounce La Chasse, after Le Livre du Chasse, a hunting manual by and fight off the surface, causing her still lifes to dance with Gaston Phébus from the fourteenth century. Skaer was agitated energy. By treating her ‘subject’ and background compelled by illustrations in this medieval manuscript with the same process, the traditional focal point of the work for their representation of time and form. -

Graeme Todd the View from Now Here

GRAEME TODD The View from Now Here 1 GRAEME TODD The View from Now Here EAGLE GALLERY EMH ARTS ‘But what enhanced for Kublai every event or piece of news reported by his inarticulate informer was the space that remained around it, a void not filled by words. The descriptions of cities Marco Polo visited had this virtue: you could wander through them in thought, become lost, stop and enjoy the cool air, or run off.’ 1 I enjoy paintings that you can wander through in thought. At home I have a small panel by Graeme Todd that resembles a Chinese lacquer box. In the distance of the image is the faint tracery of a fallen city, caught within a surface of deep, fiery red. The drawing shows only as an undercurrent, overlaid by thinned- down acrylic and layers of varnish that have been polished to a silky patina. Criss-crossing the topmost surface are a few horizontal streaks: white tinged with purple, and bright, lime green. I imagine they have been applied by pouring the paint from one side to the other – the flow controlled by the way that the panel is tipped – this way and that. I think of the artist in his studio, holding the painting in his hands, taking this act of risk. Graeme Todd’s images have the virtue that, while at one glance they appear concrete, at another, they are perpetually fluid. This is what draws you back to look again at them – what keeps them present. It is a pleasure to be able to host The View from Now Here at the Eagle Gallery, and to work in collaboration with Andrew Mummery, who is a curator and gallerist for whom I have a great deal of respect. -

Jim Lambie Education Solo Exhibitions & Projects

FUNCTIONAL OBJECTS BY CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS ! ! ! ! !JIM LAMBIE Born in Glasgow, Scotland, 1964 !Lives and works in Glasgow ! !EDUCATION !1980 Glasgow School of Art, BA (Hons) Fine Art ! !SOLO EXHIBITIONS & PROJECTS 2015 Anton Kern Gallery, New York, NY (forthcoming) Zero Concerto, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, Australia Sun Rise, Sun Ra, Sun Set, Rat Hole Gallery, Tokyo, Japan 2014 Answer Machine, Sadie Coles HQ, London, UK The Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland 2013 The Flowers of Romance, Pearl Lam Galleries, Hong Kong! 2012 Shaved Ice, The Modern Institute, Glasgow, Scotland Metal Box, Gerhardsen Gerner, Berlin, Germany you drunken me – Jim Lambie in collaboration with Richard Hell, Arch Six, Glasgow, Scotland Everything Louder Than Everything Else, Franco Noero Gallery, Torino, Italy 2011 Spiritualized, Anton Kern Gallery, New York, NY Beach Boy, Pier Art Centre, Orkney, Scotland Goss-Michael Foundation, Dallas, TX 2010 Boyzilian, Galerie Patrick Seguin, Paris, France Jupiter Artland, Edinburgh, Scotland Metal Urbain, The Modern Institute, Glasgow, Scotland! 2009 Atelier Hermes, Seoul, South Korea ! Jim Lambie: Selected works 1996- 2006, Charles Riva Collection, Brussels, Belgium Television, Sadie Coles HQ, London, UK 2008 RSVP: Jim Lambie, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA ! Festival Secret Afair, Inverleith House, Ediburgh, Scotland Forever Changes, Glasgow Museum of Modern Art, Glasgow, Scotland Rowche Rumble, c/o Atle Gerhardsen, Berlin, Germany Eight Miles High, ACCA, Melbourne, Australia Unknown Pleasures, Hara Museum of -

Edinburgh Galleries Artist Training Programme

Copyright © Art, Design & Museology Department, 2005 Published by: Art, Design & Museology Department School of Arts & Humanities Institute of Education University of London 20 Bedford Way London WC1H 0AL UK All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN: 0-9546113-1-4 This project was generously supported by: The National Lottery, The City of Edinburgh Council and National Galleries of Scotland 1 The Edinburgh Galleries Artist Training Programme in collaboration with the Art, Design & Museology department, School of Arts & Humanities, Institute of Education, University of London A pilot programme supported by The National Lottery, The City of Edinburgh Council and National Galleries of Scotland Course Directors: Lesley Burgess, Institute of Education, University of London (IoE) Maureen Finn, National Galleries of Scotland Course Co-ordinator: Kirsty Lorenz Course Venues: Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh Participating Organisations: The Collective Gallery Edinburgh Printmakers Workshop Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop The Fruitmarket Gallery Stills Gallery Talbot Rice Gallery Course Leader: Lesley Burgess, IoE Session contributors: Nicholas Addison, IoE Lesley Burgess, IoE Anne Campbell, SAC Barbara Clayton Sucheta Dutt, SAC Fiona Marr Sue Pirnie, SAC Roy Prentice, IoE Helen Simons Rebecca Sinker, DARE and inIVA Sally Tallant, Serpentine Gallery, London Leanne Turvey, Chisenhale Gallery, London Research Report by: Lesley Burgess and Emily Pringle Photographs by: Lesley Burgess 2 EDINBURGH GALLERIES ARTIST TRAINING PROGRAMME RESEARCH EVALUATION REPORT OCTOBER 2003 1. -

Scottish Art: Then and Now

Scottish Art: Then and Now by Clarisse Godard-Desmarest “Ages of Wonder: Scotland’s Art 1540 to Now”, an exhibition presented in Edinburgh by the Royal Scottish Academy of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture tells the story of collecting Scottish art. Mixing historic and contemporary works, it reveals the role played by the Academy in championing the cause of visual arts in Scotland. Reviewed: Tom Normand, ed., Ages of Wonder: Scotland’s Art 1540 to Now Collected by the Royal Scottish Academy of Art and Architecture, Edinburgh, The Royal Scottish Academy, 2017, 248 p. The Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) and the National Galleries of Scotland (NGS) have collaborated to present a survey of collecting by the academy since its formation in 1826 as the Scottish Academy of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. Ages of Wonder: Scotland’s Art 1540 to Now (4 November 2017-7 January 2018) is curated by RSA President Arthur Watson, RSA Collections Curator Sandy Wood and Honorary Academician Tom Normand. It has spawned a catalogue as well as a volume of fourteen essays, both bearing the same title as the exhibition. The essay collection, edited by Tom Normand, includes chapters on the history of the RSA collections, the buildings on the Mound, artistic discourse in the nineteenth century, teaching at the academy, and Normand’s “James Guthrie and the Invention of the Modern Academy” (pp. 117–34), on the early, complex history of the RSA. Contributors include Duncan Macmillan, John Lowrey, William Brotherston, John Morrison, Helen Smailes, James Holloway, Joanna Soden, Alexander Moffat, Iain Gale, Sandy Wood, and Arthur Watson. -

Janice Mcnab — Curriculum Vitae

Janice McNab — Curriculum vitae Born in Aberfeldy, Scotland. Lives and works in The Hague. EDUCATION 2019 PhD, Amsterdam School for Cultural Analysis, University of Amsterdam 1997 MFA, Glasgow School of Art. Exchange to Hunter College of the Arts, New York 1986 BA, Edinburgh College of Art EMPLOYMENT 2020–2022 Post-doc researcher, ACPA, University of the Arts, The Hague and Leiden University 2015–ongoing Head, MA Artistic Research, The Royal Academy of Art, The Hague Previous teaching experience includes: 2013–2015 Thesis supervisor, Piet Zwart Masters Institute, Rotterdam 2011–2015 Thesis supervisor, Gerrit Rietveld Academy, Amsterdam 2009–2015 Studio tutor, The Royal Academy of Art, The Hague 2006–2008 Thesis supervisor, Piet Zwart Masters Institute, Rotterdam 1997–1999 Studio tutor, Glasgow School of Art External examiner, visiting artist and guest lecturer at various art schools across Britain and Europe, including, in 2020, lectures for DutchCulture.nl Brexit debates and ASCA, University of Amsterdam 30th anniversary conference. OTHER PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2018–ongoing Chair, Board of 1646 Experimental Art Space, The Hague 2009–2015 Co-editor, If I Can’t Dance Publications, Amsterdam 2008–2009 Mentor, My Miyagi Young Curator programme, Stichting Mama, Rotterdam 2006–2009 Co-curator, Artis Den Bosch, Art Space, ‘s Hertogenbosch 1/4 SELECTED EXHIBITIONS AND PROJECTS 2020 Slits and a Skull, Bradwolff Projects, Amsterdam A New World, Stroom, The Hague 2016 Hollandaise, The Dutch Embassy and New Art Projects, London 2015 Undone, Bradwolff -

How to Find Us

THE GLASGOW SCHOOL OF ART LOCATIONS Whisky Bond Possil Road Dawson Road Stow Building Garscube Road West Graham Street COWCADDENS Garnethill Craighall Road Craighall Cathedral Street Eastvale Place BUCHANAN STREET Kelvinhaugh Street North Hanover Street ST ENOCH The Pacific Quay Hub IBROX Garnethill Campus Highlands & Islands Campus (not pictured) See detailed section on reverse page Innovation School studios and workshops Visitor information at gsadesigninnovation.com Stow Building Altyre Estate, Forres IV36 2SH School of Fine Art studios and workshops 43 Shamrock Street, G4 9LD GSofA Singapore (not pictured) Communication Design and Interior Design studios The Hub and workshops School of Simulation and Visualisation studios and workshops Visitor information at gsa.ac.uk/singapore Visitors should report to the reception on the ground floor SIT@TP, Singapore 528694 70 Pacific Quay, G51 1EA Whisky Bond Archives & Collections Centre Access by appointment – contact [email protected] 2 Dawson Road, G4 9SS Contact The Glasgow School of Art 167 Renfrew Street Glasgow G3 6RQ +44(0)141 353 4500 [email protected] THE GLASGOW SCHOOL OF ART GARNETHILL CAMPUS ENTRANCE SHAMROCK STREET 14 WEST GRAHAM STREET GARNETHILL STREET GARNETSTREET 6 BUCCLEUCH STREET STREET DALHOUSIE 7 4-5 HILL STREET ROSE STREET ROSE CAMBRIDGE STREET 9 2 1 10 ENTRANCE RENFREW STREET 3 STREET SCOTT 13 GFT 8 SAUCHIEHALL STREET BATH STREET 11 12 WEST REGENT STREET Road closures Road closures 1 Reid Building 8 Rose Street 3D Making Workshops, Fashion + Textiles Workshops, Administration Offices for Specialist Schools, Laser Cutting, Media Studio + Store, Photo Print Development, Finance, Health and Safety, Prototyping Workshop, School of Design Studios, HR, Information Technology, Registry Silversmithing & Jewellery Workshop 9 No. -

Dalziel + Scullion – CV

Curriculum Vitae Dalziel + Scullion Studio Dundee, Scotland + 44 (0) 1382 774630 www.dalzielscullion.com Matthew Dalziel [email protected] 1957 Born in Irvine, Scotland Education 1981-85 BA(HONS) Fine Art Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design, Dundee 1985-87 HND in Documentary Photography, Gwent College of Higher Education, Newport, Wales 1987-88 Postgraduate Diploma in Sculpture and Fine Art Photography, Glasgow School of Art Louise Scullion [email protected] 1966 Born in Helensburgh, Scotland Education 1984-88 BA (1st CLASS HONS) Environmental Art, Glasgow School of Art Solo Exhibitions + Projects 2016 TUMADH is TURAS, for Scot:Lands, part of Edinburgh’s Hogmanay Festival, Venue St Pauls Church Edinburgh. A live performance of Dalziel + Scullion’s multi-media art installation, Tumadh is Turas: Immersion & Journey, in a "hauntingly atmospheric" venue with a live soundtrack from Aidan O’Rourke, Graeme Stephen and John Blease. 2015 Rain, Permanent building / pavilion with sound installation. Kaust, Thuwai Saudia Arabia. Nomadic Boulders, Permanent large scale sculptural work. John O’Groats Scotland, UK. The Voice of Nature,Video / film works. Robert Burns Birthplace Museum. Alloway, Ayr, Scotland, UK. 2014 Immersion, Solo Festival exhibition, Dovecot Studios, Edinburgh as part of Generation, 25 Years of Scottish Art Tumadh, Solo exhibition, An Lanntair Gallery, Stornoway, Outer Hebrides, as part of Generation, 25 Years of Scottish Art Rosnes Bench, permanent artwork for Dumfries & Galloway Forest 2013 Imprint, permanent artwork for Warwick University Allotments, permanent works commissioned by Vale Of Leven Health Centre 2012 Wolf, solo exhibition at Timespan Helmsdale 2011 Gold Leaf, permanent large-scale sculpture. Pooley Country Park, Warwickshire. -

Robert Maclaurin

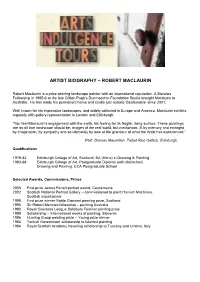

ARTIST BIOGRAPHY – ROBERT MACLAURIN Robert Maclaurin is a prize winning landscape painter with an international reputation. A Menzies Fellowship in 1995-6 at the late Clifton Pugh's Dunmoochin Foundation Studio brought Maclaurin to Australia. He has made his permanent home and studio just outside Castlemaine since 2001. Well known for his impressive landscapes, and widely collected in Europe and America, Maclaurin exhibits regularly with gallery representation in London and Edinburgh. “You feel Maclaurin’s engagement with the earth, his feeling for its fragile, living surface. These paintings are as all true landscape should be; images of the real world, but metaphoric, lit by memory and enlarged by imagination, by sympathy and so ultimately by awe at the grandeur of what the Artist has experienced.” Prof. Duncan Macmillan, Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh. Qualifications 1979-83 Edinburgh College of Art, Scotland, BA (Hons) in Drawing & Painting 1983-84 Edinburgh College of Art, Postgraduate Diploma (with distinction) Drawing and Painting, ECA Postgraduate School Selected Awards, Commissions, Prizes 2005 First prize James Farrell portrait award, Castlemaine 2002 Scottish National Portrait Gallery – commissioned to paint Hamish MacInnes, Scottish mountaineer 1998 First prize winner Noble Grossart painting prize, Scotland 1995 Sir Robert Menzies fellowship – painting Australia 1990 Royal Overseas League Salisbury Festival painting prize 1989 Scholarship – International weeks of painting, Slovenia 1986 Hunting Group painting prize – Young -

Helen Flockhart CV

HELEN FLOCKHART Arusha Gallery | [email protected] | 0131 557 1412 BIOGRAPHY Following her attainment of a first-class undergraduate degree in painting at the Glasgow School of Art in 1984, Helen Flockhart took up postgraduate study with the British Council at the State Higher School of Fine Art in Poznan, Poland. Boasting an impressive resume of solo exhibitions, spanning both Scotland and England, as well as group shows in New York, Ontario, Rotterdam, London and Truro, Flockhart was recently awarded the Concept Fine Art Award (2016), the Royal Scottish Academy’s Maude Gemmel Hutchinson Prize (2012), and the Lyon and Turnbull Award presented by the Royal Glasgow Institute (2012). A fellow of the Glasgow Art Club (as of 1997), Flockhart’s works belong to such prestigious collections as the Fleming Collection, the Scottish Arts Council, Strathclyde University and the Lillie. Bill Hare, teaching fellow of Modern and Contemporary Scottish Art at the University of Edinburgh, praises her work. ‘Nobody paints like Helen Flockhart’, he writes: ‘here the mundane and the mythical are at one with each other’. Hers are works which break with established convention -- a blend of portrait and landscape, Flockhart’s paintings are verdant, fantastical paeans to that particularist genre of British myth making centered on pastures, mountains and divinity. Indeed, there is something Blakean about her work -- a warmth of vision borne of what appears simultaneous ancient and modern. EDUCATION 1985-1986 Studied painting at the State Higher School of