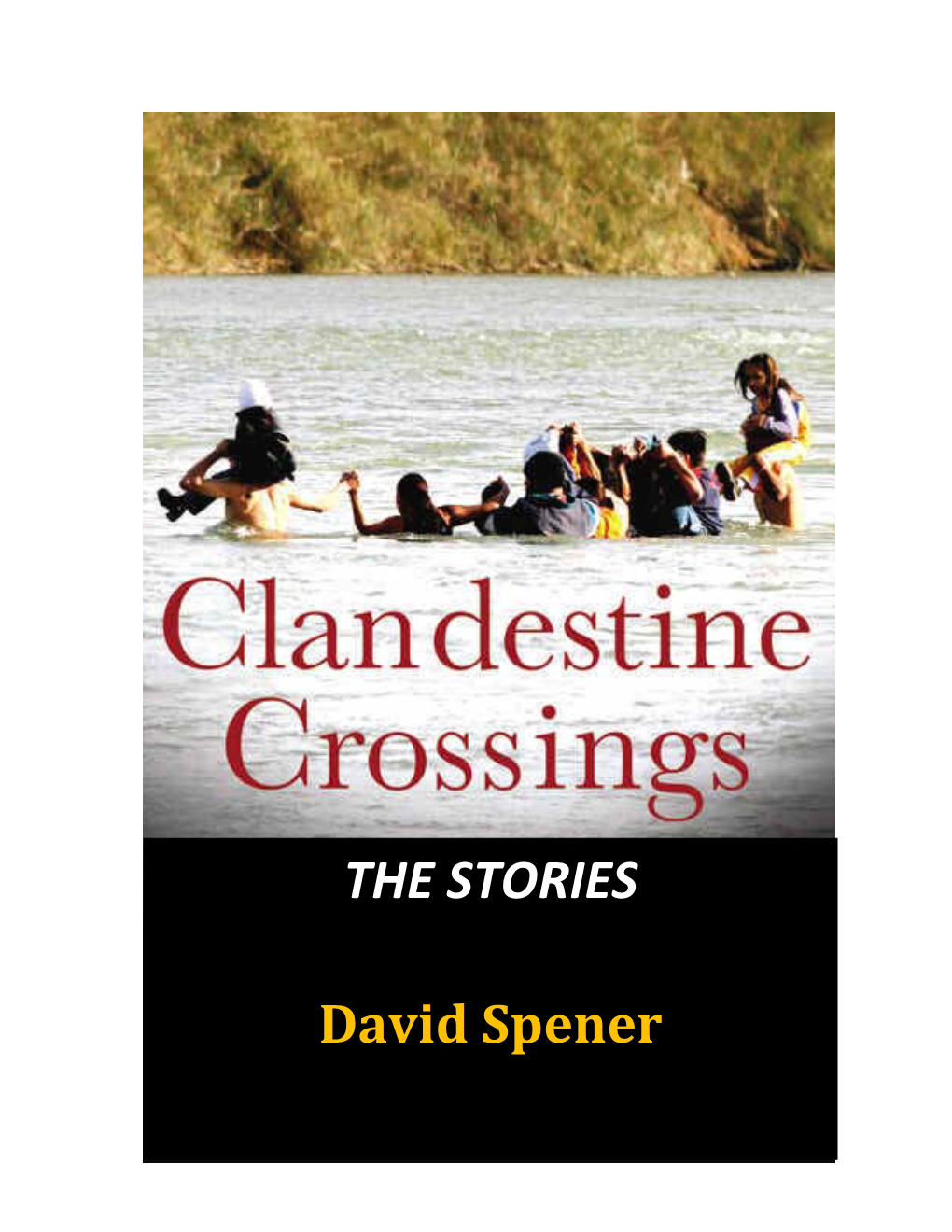

THE STORIES David Spener

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9111-14 Department of Homeland

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 12/28/2012 and available online at http://federalregister.gov/a/2012-31328, and on FDsys.gov 9111-14 DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY 8 CFR Part 100 U.S. Customs and Border Protection 19 CFR Part 101 Docket No. USCBP-2011-0032 CBP Dec. No. 12-23 RIN 1651-AA90 Opening of Boquillas Border Crossing and Update to the Class B Port of Entry Description AGENCY: U.S. Customs and Border Protection, DHS. ACTION: Final rule. SUMMARY: This rule establishes a border crossing in Big Bend National Park called Boquillas and designates it as a Customs station for customs purposes and a Class B port of entry (POE) for immigration purposes. The Boquillas crossing will be situated between Presidio and Del Rio, Texas. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and the National Park Service (NPS) are partnering on the construction of a joint use facility in Big Bend National Park where the border crossing will operate. This rule also updates the description of a Class B port of entry to reflect current border crossing documentation requirements. EFFECTIVE DATE: [Insert date 30 days after date of publication of this document in the Federal Register.] FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Colleen Manaher, Director, Land Border Integration, CBP Office of Field Operations, telephone 202-344-3003. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: This rule establishes a border crossing in Big Bend National Park called Boquillas and designates it as a Customs station for customs purposes and a Class B port of entry for immigration purposes. -

THE STORIES David Spener

THE STORIES David Spener CCllaannddeessttiinnee CCrroossssiinnggss:: TThhee SSttoorriieess © 2010 by David Spener, Ph.D. Department of Sociology and Anthropology Trinity University San Antonio, Texas U.S.A. Published electronically by the author at http://www.trinity.edu/clandestinecrossings as a companion to the book Clandestine Crossings: Migrants and Coyotes on the Texas-Mexico Border (Cornell University Press, 2009). Direct correspondence to [email protected]. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1 It Was a Lot of Money, but It Was Worth It 6 Chapter 2 El Carpintero 32 Chapter 3 Divided Lives 36 Chapter 4 Se batalla mucho 78 Chapter 5 You Can Cross Any Time You Want 108 Chapter 6 From Matamoros to Houston 128 Chapter 7 I Helped Them Because I Had Suffered, Too 157 Chapter 8 Criminal Enterprise or Christian Charity? 176 Chapter 9 Sandra, in San Antonio, on Her Way to Seattle 198 Bilingual Glossary of Migration-Related Terms 215 Entre tu pueblo y mi pueblo Between your people and my people, hay un punto y una raya. there are a dot and a dash. La raya dice “No hay paso,” The dash says, “No Crossing,” y el punto “Vía cerrada.” and the dot, “Road Closed.” Y así entre todos los pueblos And that’s how it is between all the raya y punto, punto y raya. peoples: Dash and dot, dash and dot. Con tantas rayas y puntos With so many dashes and dots, el mapa es un telegrama. the map is a telegram. Caminando por el mundo Walking through this world, se ven ríos y montañas you’ll see rivers and mountains. -

Foundation Document Big Bend National Park Texas May 2016 Foundation Document

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Big Bend National Park Texas May 2016 Foundation Document Unpaved road Trail Ruins S A N 385 North 0 5 10 Kilometers T Primitive road Private land within I A Rapids G 0 5 10 Miles (four-wheel-drive, park boundary O high-clearance Please observe landowner’s vehicles only) BLACK GAP rights. M WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT AREA Persimmon Gap O U N T A Stillwell Store and RV Park Graytop I N S Visitor Center on Dog Cany Trail d o a nch R 2627 TEXAS Ra a u ng Te r l i 118 Big Bend Dagger Mountain Stairway Mountain S I National Park ROSILLOS MOUNTAINS E R R A DAGGER Camels D r Packsaddle Rosillos e FLAT S Hump E v i l L I Mountain Peak i E R a C r R c Aqua Fria A i T R B n A Mountain o A e t CORAZONES PEAKS u c lat A L ROSILLOS gger F L S Da O L O A d RANCH ld M R n G a Hen Egg U O E A d l r R i Mountain T e T O W R O CHRI N R STM I A Terlingua Ranch o S L L M O a e O d d n U LA N F a TA L r LINDA I A N T G S Grapevine o d Fossil i a Spring o Bone R R THE Exhibit e Balanced Rock s G T E L E P d PAINT GAP l H l RA O N n SOLITARIO HILLS i P N E N Y O a H EV ail C A r Slickrock H I IN r LL E T G Croton Peak S S Mountain e n Government n o i I n T y u Spring v Roys Peak e E R e le n S o p p a R i Dogie h C R E gh ra O o u G l n T Mountain o d e R R A Panther Junction O A T O S Chisos Mountains r TERLINGUA STUDY BUTTE/ e C BLACK MESA Visitor Center Basin Junction I GHOST TOWN TERLINGUA R D Castolon/ Park Headquarters T X o o E MADERAS Maverick Santa Elena Chisos Basin Road a E 118 -

Maderas Del Carmen

PROGRAMA DE MANEJO MADERAS DEL CARMEN I. PRESENTACIÓN El 7 de noviembre de 1994, se publicó en el Diario Oficial de la Federación el decreto mediante el cual se establece el Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Maderas del Carmen. En dicho decreto se justifica la creación de una nueva área natural protegida de 208,381 ha. de superficie, como una estrategia para conservar los valores naturales de un sitio en el que actualmente existen organismos de gran importancia biológica y también porque estas montañas forman parte de un corredor natural a través del cual se desplazan numerosas especies de animales y se dispersan diversas especies de plantas. La creación de esta nueva área protegida, es la respuesta a la demanda de investigadores, manejadores de áreas protegidas, políticos y organizaciones no gubernamentales, que durante 60 años han alentado la idea de proteger estas sierras: tanto por su valor intrínseco, como por la posibilidad de que, junto con el Parque Nacional Big Bend, el Área de Manejo de Black Gap, y el Parque Estatal Big Bend Ranch, en Texas, y ahora con el Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Cañón de Santa Elena, en Chihuahua, sean en conjunto una de las superficies protegidas más extensas entre los dos países. De esta forma, los recursos más representativos del Desierto Chihuahuense quedarían prácticamente asegurados. Las intenciones de proteger este lugar se inician en 1935 y, aunque no se presentan de una forma constante durante todo ese tiempo, se manifiestan repetidamente hasta alcanzar su propósito en 1994. La región más estudiada en esa área por nacionales y extranjeros, es Maderas del Carmen, debido a las características que como "Isla del Cielo" tiene, y posteriormente, al reconocimiento de su valor como centro de dispersión y refugio para muchas especies. -

A Little Fish in Big Bend Rio Grande Silvery Minnow Showing Signs of Reproduction in Texas

By Aimee Roberson A Little Fish in Big Bend Rio Grande silvery minnow showing signs of reproduction in Texas The Rio Grande silvery minnow life; they provide clean water and flashes silver in sunlight, but it’s no abundant fisheries, and buffer people trophy fish. Too small in size to be from flooding. However, people have of interest to anglers, the silvery taken their toll on the Rio Grande—it minnow is a little fish with a big story. is fundamentally different than the At one time, the silvery minnow wild, free-flowing river it once was. swam in large schools and was one Many species, including the silvery of the most common fishes in the minnow, have declined. Rio Grande from Española, New Mexico, to the Gulf of Mexico. But In the current chapter of the silvery the Rio Grande was bigger then, más minnow’s story, the U.S. Fish and grande. Today, the silvery minnow Wildlife Service returned it to its is an endangered species, and until former home in the Big Bend reach recently, existed in only seven of the Rio Grande, taking a critical percent of its historic range near step toward the fish’s recovery. The Albuquerque, New Mexico. Big Bend reach flows through the heart of the northern Chihuahuan The silvery minnow’s absence from Desert, surrounded by nearly three most of its historic range reflects the million acres of public and private fact that the Rio Grande where the conservation lands in Texas and silvery minnow once thrived, suffers. Mexico. The river courses through The story of the Rio Grande and its Big Bend National Park and is the silvery minnow is similar to stories essence of the 196-mile-long Rio all over the world, where people take Grande Wild and Scenic River. -

APORTE NUTRICIONAL DEL ECOSISTEMA DE MADERAS DEL CARMEN, COAHUILA, PARA EL OSO NEGRO (Ursus Americanas Eremicus)"

FACULTAD DE QENCXAS KMIKSTAIJES "Arnim* mmaciONäi« OKÍ« vmsssmmk i>K MADERAS DKi« C&UMHN, OOAHOBA OSO NËXM) {V/hm» mmvmvwn mmewmm)" TESIS DE MAESTRIA COMO RfiQuisrro PARCIAL PARA OBTENER EL GRADO DE Mfw'tmio m oîmoas mwtsTAiss (W*. Disama F, Hcama Gauáb. !( «tnan», Nwïvo 11 ¿xtu N(T6W:MÎmî do 2003 TM Z59y i FCF 2003 • H4 1020149286 C/AN U "APORTE NUTRICIONAL DEL ECOSISTEMA DE MADERAS DEL CARMEN, COAHUILA, PARA EL OSO NEGRO (Ursus americanas eremicus)" TESIS DE MAESTRIA COMO REQUISITO PARCIAL PARA OBTENER EL GRADO DE MAESTRO EN CIENCIAS FORESTALES POR: MVZ. Diana E. Herrera González Linares, Nuevo León. Noviembre de 2003 Wf » FONDO TESIS "APORTE NUTRICIONAL DEL ECOSISTEMA DE MADERAS DEL CARMEN, COAHUILA, PARA EL OSO NEGRO (Ursus ameritan us eremicus)" TESIS DE MAESTRIA PARA OBTENER EL GRADO DE MAESTRO EN CIENCIAS FORESTALES COMITE DE TESIS INDICE DE TEXTO 1. INTRODUCCIÓN 1 2. OBJETIVOS 2 2.1. General 2 2.2. Específicos 2 3. ANTECEDENTES 3 3.1. Clasificación taxonómica 3 3.2. Distribución 4 33. Densidad poblacional 7 3.4. Hábitat utilizado 10 3.5. Alimentación y nutrición estacional 10 3.6. Hábitos alimenticios 13 3.7. Producción de alimento 17 3.8. Requerimientos energéticos y capacidad de carga 19 4. MATERIALES Y MÉTODOS 21 4.1. Área de estudio 21 4.1.1. Descripción geográfica 22 4.1.2. Clima 22 4.1.3. Hidrología 24 4.1.4. Geología 24 4.1.5. Suelos 25 4.1.6. Características bióticas 25 4.1.6.1. Comunidades animales 25 4.1.6.2. Comunidades vegetales 26 4.2. -

Handbook on Marketing Transnational Tourism Themes and Routes

Handbook on Marketing Transnational Tourism Themes and Routes Fundada en 1948, la Comisi—n Europea de Turismo (CET) es una organizaci—n sin ‡nimo de lucro cuyo papel es comercializar y p romover Europa como destino tur’stico en los mercados extranjeros. Los miembros de la CET son las organizaciones nacionales de turismo (ONTs) de treinta y tres pa’ses europeos. Su misi—n es proporcionar valor a–adido a los miembros alentando el intercambio de informaci—n y habilidades de gesti—n as’ como concienciar sobre el papel que juegan las ONTs. http://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284419166 - Monday, January 15, 2018 6:44:02 AM Université du Québec à Montréal IP Address:132.208.45.83 http://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284419166 - Monday, January 15, 2018 6:44:02 AM Université du Québec à Montréal IP Address:132.208.45.83 Handbook on Marketing Transnational Tourism Themes and Routes http://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284419166 - Monday, January 15, 2018 6:44:02 AM Université du Québec à Montréal IP Address:132.208.45.83 Copyright © 2017, World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and European Travel Commission (ETC) Cover photo: Copyright © Olga Danylenko Handbook on Marketing Transnational Tourism Themes and Routes ISBN UNWTO: printed version: 978-92-844-1915-9 electronic version: 978-92-844-1916-6 ISBN ETC: printed version: 978-92-95107-11-3 electronic version: 978-92-95107-10-6 Published by the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and the European Travel Commission (ETC). Printed by the World Tourism Organization, Madrid, Spain. -

Zonificación Del Área De Protección De Flora Y Fauna Maderas Del

Zonificación del Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Maderas del Carmen, Coahuila Secretaría de Medio Ambiente, Recursos Superficie total: 208, 381 ha Naturales y Pesca SPP H13-9, H13-12 N Ej. Melchor Múzquiz 1Aa O E Estados Unidos de América 2A 1Ab S 2B Río Bravo 3B 1Ba Boquillas del Carmen 3Cb 3A Ej. J. Ma. Morelos 4Ca 1Ac 4Ba 4Ca 3Ca 4Ac Simbología / Zonificación Norias de Boquillas Zona Natural sobresaliente Zona silvestre 4Cb Zona de aprovechamiento Zona de recuperación Simbología Convencional Carretera Estatal No. 2 1Ad Múzquiz-Boquillas 4Ab Camino de Terracería Jaboncillos 4Aa Santo Domingo Camino Secundario 4Cc El Mezquite 4Bb Unidades Ambientales 1Aa Río Bravo Ej. San Francisco 1Ab Melchor Múzquiz 1Ac Carranza-Morelos 1Ad Guadalupe-Sto. Domingo 1Ae Los Lirios-San Francisco 4Cc 1Af La Florida-Los Venados Los Pilares 1Ae 1Ba Boquillas-Jaboncillos 1Bb 1Bb Torreoncito-Morteros 2A Cañón de Boquillas 2B Cañón del Diablo 3A Jardín Oeste Ej. Los Lirios 3B Jardín Este 3C Cañón Jardín 3Ca Cañón Oeste, La Rinconada 3Cb Cañón Este 4Aa Aserraderos 1Af Coahuila 4Ab Pilote del Mábrico 4Ac El Centinela 4Ba El Centinela 4Bb Maderas del Carmen 4Ca El Centinela Coahuila 4Cb Cañón del Burro 4Cc Cañón El Álamo Programa de Manejo del Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Maderas del Carmen Julia Carabias Lillo Secretaria de Medio Ambiente, Recursos Naturales y Pesca Gabriel Quadri de la Torre Presidente del Instituto Nacional de Ecología Javier de la Maza Elvira Jefe de la Unidad Coordinadora de Áreas Naturales Protegidas © 1a edición: mayo de 1997 Instituto Nacional de Ecología Av. -

Foundation Document, Big Bend National Park

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Big Bend National Park Texas May 2016 Foundation Document Unpaved road Trail Ruins S A N 385 North 0 5 10 Kilometers T Primitive road Private land within I A Rapids G 0 5 10 Miles (four-wheel-drive, park boundary O high-clearance Please observe landowner’s vehicles only) BLACK GAP rights. M WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT AREA Persimmon Gap O U N T A Stillwell Store and RV Park Graytop I N S Visitor Center on Dog Cany Trail d o a nch R 2627 TEXAS Ra a u ng Te r l i 118 Big Bend Dagger Mountain Stairway Mountain S I National Park ROSILLOS MOUNTAINS E R R A DAGGER Camels D r Packsaddle Rosillos e FLAT S Hump E v i l L I Mountain Peak i E R a C r R c Aqua Fria A i T R B n A Mountain o A e t CORAZONES PEAKS u c lat A L ROSILLOS gger F L S Da O L O A d RANCH ld M R n G a Hen Egg U O E A d l r R i Mountain T e T O W R O CHRI N R STM I A Terlingua Ranch o S L L M O a e O d d n U LA N F a TA L r LINDA I A N T G S Grapevine o d Fossil i a Spring o Bone R R THE Exhibit e Balanced Rock s G T E L E P d PAINT GAP l H l RA O N n SOLITARIO HILLS i P N E N Y O a H EV ail C A r Slickrock H I IN r LL E T G Croton Peak S S Mountain e n Government n o i I n T y u Spring v Roys Peak e E R e le n S o p p a R i Dogie h C R E gh ra O o u G l n T Mountain o d e R R A Panther Junction O A T O S Chisos Mountains r TERLINGUA STUDY BUTTE/ e C BLACK MESA Visitor Center Basin Junction I GHOST TOWN TERLINGUA R D Castolon/ Park Headquarters T X o o E MADERAS Maverick Santa Elena Chisos Basin Road a E 118 -

Border-Wall-Comment-Congressman

I. The border wall will have a detrimental effect on U.S. – Mexico relations. The United States and Mexico are geographically, economically, historically, and culturally connected. We are trading partners, allies, brothers, sisters, and cousins whose relationship spans familial connection and security cooperation. Border towns in South Texas and beyond – where the border wall is planned to be built – are the epicenter of this multifaceted and longstanding relationship. Having already witnessed the adverse economic, social, and political effects of physical barriers that harshly divide our intrinsically connected communities, those of us in living and working along the U.S.-Mexico border know that a border wall will weaken and sever the strong ties between our two countries. The town of Boquillas del Carmen, Coahuila, Mexico, located across the Rio Grande River from Big Bend National Park, is just one example of the damage that could be done, and mistakes that do not bear repeating. Until 2002, Boquillas del Carmen relied heavily on tourist traffic.1 In 2002, when the border crossing connecting Las Boquillas to the U.S. was shut down, the town was devastated. Without the economic stimulation of tourism and travel, Boquillas del Carmen came to depend on food donations from charitable organizations. Eleven years later, the entry was re-opened, allowing visitors with a valid passport, and enough money to pay for a ride in a rowboat, to cross the border.2 Boquillas del Carmen now boasts a record number of visitors from around the world. If a physical barrier is erected, this border town and many like it, will fade away. -

9111-14 Adm-9-03 Ot:Rr:Rd:Bs H141399 Maw Department

9111-14 ADM-9-03 OT:RR:RD:BS H141399 MAW DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY U.S. Customs and Border Protection 8 CFR Part 100 19 CFR Part 101 Docket No. USCBP-2011-0032 RIN 1651-AA90 Opening of Boquillas Border Crossing and Update to the Class B Port of Entry Description AGENCY: U.S. Customs and Border Protection, DHS. ACTION: Notice of Proposed Rulemaking. SUMMARY: This notice of proposed rulemaking proposes to create a border crossing in Big Bend National Park to be called Boquillas. The Boquillas crossing would be situated between Presidio and Del Rio, Texas. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and the National Park Service plan to partner on the construction of a joint use facility in Big Bend National Park where the border crossing would operate. This NPRM proposes to designate the Boquillas border crossing as a “Customs station” for customs purposes and a Class B port of entry for immigration purposes. This NPRM also proposes to update the description of a Class B port of entry to reflect current border crossing documentation requirements. DATES: Comments must be received on or before [INSERT DATE 60 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER] ADDRESSES: You may submit comments identified by docket number, by one of the following methods: • Federal eRulemaking Portal: http://www.regulations.gov. Follow the instructions for submitting comments via docket number USCBP-2011-0032. • Mail: Border Security Regulations Branch, Office of International Trade, Customs and Border Protection, Regulations and Rulings, Attention: Border Security Regulations Branch, 799 9th Street, NW, 5th Floor, Washington, DC 20229-1179. -

You Can Cross Any Time You Want

You Can Cross Any Time You Want ©2010 by David Spener1 Beto was a coyote who had been deported from the United States after being arrested while driving a van full of migrants near Alpine, Texas, just north of Big Bend National Park. He had lived and worked for five years in Austin, Texas in the late 1990s before his arrest. When I met him in 2002, Beto was living back home in the small town of La Cancha, Nuevo León, working as a recruiter of customers for a group of coyotes based at the border in Piedras Negras, Coahuila. In our interviews he told me how he came to be a coyote, how the groups he had worked with operated, how the business of moving migrants across the border had changed in recent years, and how he viewed his future as a coyote. I wound up in the small town of La Cancha, Nuevo León in 2002 by traveling there with the father of a Mexican American woman I knew in San Antonio, Texas. She was from the McAllen area in South Texas and her father, Rigoberto, had grown up in La Cancha before moving to the United States as an adult.2 I had told her about my interest in hearing migrants’ border‐crossing stories and she directed me to her father, who offered to go with me to La Cancha to introduce me to his friends and family there, who could tell me more about the town’s experience with sending its residents to live and work in the United States.