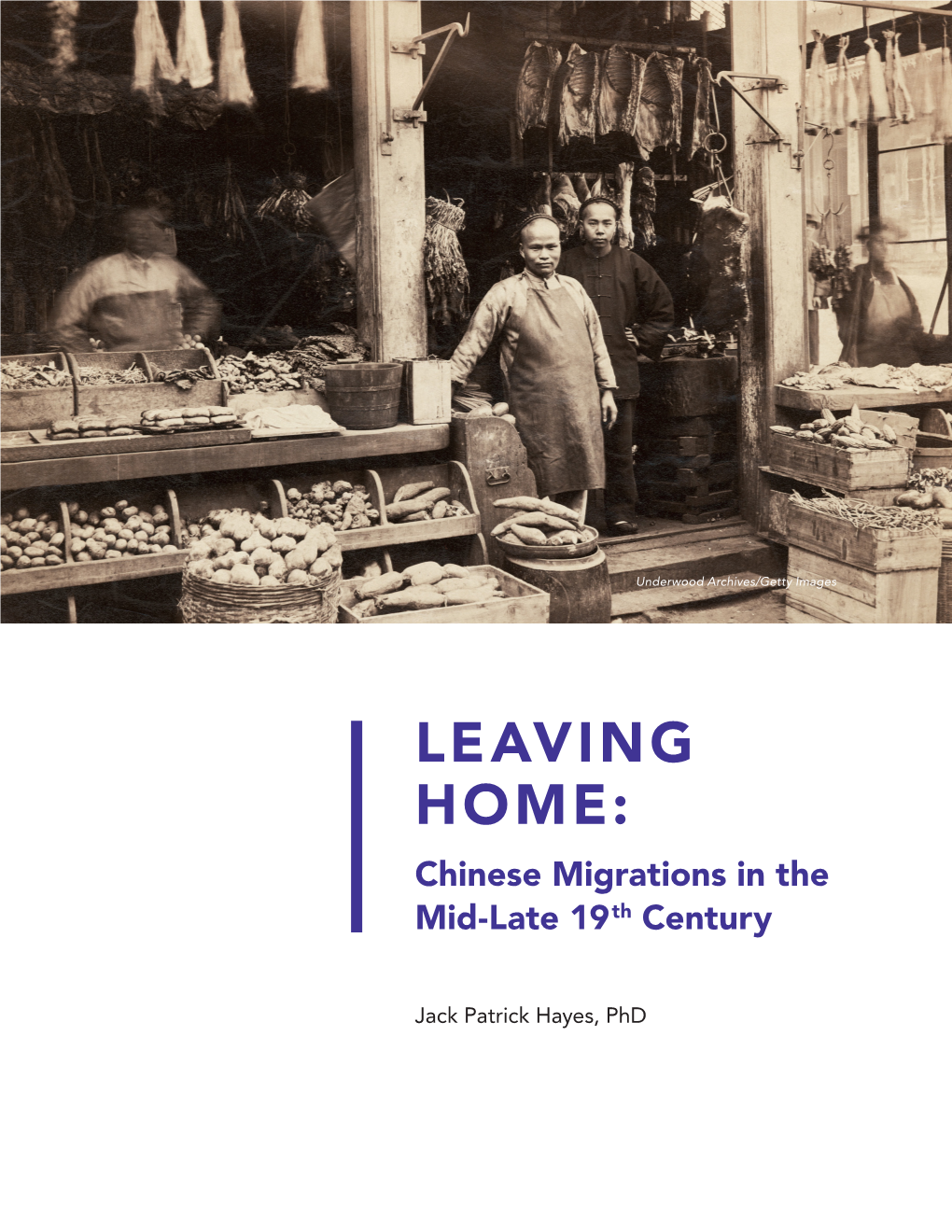

LEAVING HOME: Chinese Migrations in the Mid-Late 19Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taiping Rebellion PMUNC 2017

Taiping Rebellion PMUNC 2017 Princeton Model United Nations Conference 2017 The Taiping Rebellion Chair: Nicholas Wu Director: [Name] 1 Taiping Rebellion PMUNC 2017 CONTENTS Letter from the Chair……………………………………………………………… 3 The Taiping Rebellion:.…………………………………………………………. 4 History of the Topic………………………………………………………… 4 Current Status……………………………………………………………….7 Country Policy……………………………………………………………… 9 Keywords…………………………………………………………………...11 Questions for Consideration………………………………………………...12 Positions:.………………………………………………………………………. 14 2 Taiping Rebellion PMUNC 2017 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR Dear Delegates, Welcome to PMUNC 2017! This will be my fourth and final PMUNC. My name is Nicholas Wu, and I’m a senior in the Woodrow Wilson School, pursuing certificates in American Studies and East Asian Studies. It’s my honor to chair this year’s crisis committee on the Taiping Rebellion. It’s a conflict that fascinates me. The Taiping Rebellion was the largest civil war in human history, but it barely receives any attention in your standard world history class. Which is a shame — it’s a multilayered conflict. There are ethnic, economic, and religious issues at play, as well as significant foreign involvement. I hope that you all find it as interesting as I do. On campus, I’m currently figuring out how to write my thesis, and I’m pretty sure that I’m going to be researching the implementation of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). I’m also involved with the International Relations Council, the Daily Princetonian, the Asian American Students Association, and Princeton Advocates for Justice. I also enjoy cooking. Best of luck at the conference! Please don’t hesitate to reach out if you have any questions. You can email me anytime at [email protected]. -

China's 1911 Revolution

www.hoddereducation.co.uk/historyreview Volume 23, Number 1, September 2020 Revision China’s 1911 Revolution Nicholas Fellows Test your knowledge of the 1911 Revolution in China and the events preceding it with these multiple-choice questions. Answers on the final page Questions 1 When did the First Opium War start? 1837 1838 1839 1840 2 What term was used to describe the agreements China was forced to sign with the West following its defeat? Unfair Treaties Unequal Treaties Concession Treaties Compromise Treaties 3 Which dynasty ruled china at the time of the Opium Wars? Ming Qing Yuan Song 4 When did the Second Opium War start? 1856 1857 1858 1859 5 What event started the war? Macartney incident Beijing affair Dagu Fort clash Arrow Incident 6 Which country destroyed a Chinese fleet in Fuzhou in 1884? Britain Germany France Spain 7 Which country took Korea from China in 1894? France Japan Britain Russia 8 Which country occupied much of Manchuria? Russia Japan Britain France 9 Which country took the port of Weihaiwei? Russia Japan Britain France 10 When did the Boxer rising start? 1899 1900 1901 1902 11 What provoked the start of the Boxer Rising? Loss of land Increase in the opium trade Western missionaries Development of railways Hodder & Stoughton © 2019 www.hoddereducation.co.uk/historyreview www.hoddereducation.co.uk/historyreview 12 Whose ambassador was shot at the start of the rising? German French British Russian 13 Who wrote 'The Revolutionary Army' in 1903 Sun Yat-sen Zou Rong Li Hongzhang Lu Xun 14 Who organised the Revolutionary -

International Security Cyber Issues Workshop Series

International Security Cyber Issues Workshop Series: The Future of Norms to Preserve and Enhance International Cyber Stability 9–10 February 2016 Palais des Nations, Geneva, Switzerland List of Participants Australia Costa Rica Henry FOX Roberto LEMAÎTRE PICADO Director Abogado Cyber and Space Policy International Security Dirección de Concesiones y Normas de Division Telecomunicaciones Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) Ministerio de Telecomunicaciones Hugh WATSON Jonny PAN SANABRIA First Secretary/Legal Adviser Chief Information Officer Australian Permanent Mission to the United Ministry of Science, Technology and Nations in Geneva Telecommunications Brazil Cuba Carlos Guilherme SAMPAIO FERNANDES Luis Alberto AMORÓS NUÑEZ Second Secretary Head of Department of Social and Humanitarian Permanent Representation of Brazil to the Affairs of the General Directorate on Multilateral Conference on Disarmament Affairs and International Law Ministry of Foreign Affairs Canada Chrystiane ROY Claudia PÉREZ ALVAREZ First Secretary Counsellor Cyber Policy Issues Permanent Mission of the Republic of Cuba to the Permanent Mission of Canada in Geneva United Nations, Geneva Michael WALMA* Egypt Director Hossam Eldeen Mohamed ALY Foreign Policy Planning Division and Coordinator for Deputy Assistant Minister for Disarmament Affairs Canada's Foreign Cyber Policy Ministry of Foreign Affairs Global Affairs Canada Estonia China Peter PEDAK FU Cong* Senior Lawyer Ambassador for Disarmament Affairs International Law Division, Legal Department Deputy -

Appendices, Notes

APPENDIX 1: Sample Confessions CH'U SSU ygo was a sect teacher from a village southeast of Peking. He was arrested in the fall of 1813. The rebels had considered and then rejected a plan for Ch'u Ssu to lead his men in an attack upon the imperial entourage as it returned from Jehol, and Ch'u was interrogated repeatedly about this plan. His various confessions about this and other matters, taken together with those of some of his associates, illustrate the kinds of information contained in con fessions, the reliability of such testimony, and the judicial process that produced them. A. First Interrogation of Ch'ii Ssu Memorial from the Grand Council and the Board of Punishments (KKCK 207.1, CC 18/9/24): On 9/23 we received a report from the censors for the south city [of Peking] saying that they had seized the criminal Ch'ii Ssu and [others]. They have been interrogated. The text of Ch'ii Ssu's confession is attached. Confession of Ch'ii Ssu (KKCK 208.1, 18/9/24) From T'ung district. Age thirty-six. Mother Miss Meng. Older brother Ch'ii Wen-hsiang. Wife Miss Ts'ai. My son Ch'ang-yu-r is ten. I was born the son of Ch'u Te-hsin but then I was adopted by Ch'u Wu. When I was nineteen, Liu Ti-wu brought me and Ch'ii Wen hsiang to take Ku Liang (who has since died) as our teacher. I entered the sect and recited the eight characters "Eternal Progenitor in Our Original Home in the World of True Emptiness." On the 14th day of the 8th month [of 1813] Lin Ch'ing told Liu Ti-wu to put me in charge of one to two hundred men and lead them to Yen-chiao [outside Peking] to rise up there. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX Aodayixike Qingzhensi Baisha, 683–684 Abacus Museum (Linhai), (Ordaisnki Mosque; Baishui Tai (White Water 507 Kashgar), 334 Terraces), 692–693 Abakh Hoja Mosque (Xiang- Aolinpike Gongyuan (Olym- Baita (Chowan), 775 fei Mu; Kashgar), 333 pic Park; Beijing), 133–134 Bai Ta (White Dagoba) Abercrombie & Kent, 70 Apricot Altar (Xing Tan; Beijing, 134 Academic Travel Abroad, 67 Qufu), 380 Yangzhou, 414 Access America, 51 Aqua Spirit (Hong Kong), 601 Baiyang Gou (White Poplar Accommodations, 75–77 Arch Angel Antiques (Hong Gully), 325 best, 10–11 Kong), 596 Baiyun Guan (White Cloud Acrobatics Architecture, 27–29 Temple; Beijing), 132 Beijing, 144–145 Area and country codes, 806 Bama, 10, 632–638 Guilin, 622 The arts, 25–27 Bama Chang Shou Bo Wu Shanghai, 478 ATMs (automated teller Guan (Longevity Museum), Adventure and Wellness machines), 60, 74 634 Trips, 68 Bamboo Museum and Adventure Center, 70 Gardens (Anji), 491 AIDS, 63 ack Lakes, The (Shicha Hai; Bamboo Temple (Qiongzhu Air pollution, 31 B Beijing), 91 Si; Kunming), 658 Air travel, 51–54 accommodations, 106–108 Bangchui Dao (Dalian), 190 Aitiga’er Qingzhen Si (Idkah bars, 147 Banpo Bowuguan (Banpo Mosque; Kashgar), 333 restaurants, 117–120 Neolithic Village; Xi’an), Ali (Shiquan He), 331 walking tour, 137–140 279 Alien Travel Permit (ATP), 780 Ba Da Guan (Eight Passes; Baoding Shan (Dazu), 727, Altitude sickness, 63, 761 Qingdao), 389 728 Amchog (A’muquhu), 297 Bagua Ting (Pavilion of the Baofeng Hu (Baofeng Lake), American Express, emergency Eight Trigrams; Chengdu), 754 check -

Canada Announces That It Is Ratifying the Canada-UK Trade Continuity

https://www.canada.ca/en/global-affairs/news/2021/03/minister-ng-announces-canada-is-ratifying- the-canada-united-kingdom-trade-continuity-agreement.html Minister Ng announces Canada is ratifying the Canada-United Kingdom Trade Continuity Agreement From: Global Affairs Canada News release March 19, 2021 - Ottawa, Ontario - Global Affairs Canada Canada and the United Kingdom share a profound and positive relationship – one that is built on shared history and values, and strong economic and people-to-people ties. Today, the Honourable Mary Ng, Minister of Small Business, Export Promotion and International Trade, during a call with Elizabeth Truss, the United Kingdom’s Secretary of State for International Trade, announced that Canada is ratifying the Canada-United Kingdom (U.K.) Trade Continuity Agreement (TCA). This announcement follows the Royal Assent of Bill C-18: An Act to implement the Agreement on Trade Continuity between Canada and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in the House of Commons. The Canada-U.K. TCA will provide Canadian exporters and businesses with continued preferential access to the U.K. market and 98% of Canadian products will continue to be exported to the UK tariff-free. The agreement provides much needed predictability and stability, and will support workers and businesses on both sides of the Atlantic. Canada and the U.K. are taking all necessary steps required to implement this agreement for April 1, 2021. As the Canada-U.K. TCA is meant to be an interim measure, Canada and the U.K. look forward to engaging in future negotiations on a new, high-standard and ambitious free trade agreement that will best reflect the bilateral relationship and trade priorities. -

Canada-United Kingdom Trade Continuity Agreement Economic Impact Assessment December 9, 2020

Canada-United Kingdom Trade Continuity Agreement Economic Impact Assessment December 9, 2020 Summary The Canada-United Kingdom Trade Continuity Agreement (CANADA-UK TCA) replicates the Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) on a bilateral basis. The CANADA-UK TCA, therefore, is meant to maintain the status quo in the Canada-U.K. trade relationship. In order to examine the impact of the CANADA-UK TCA, we must analyze the potential economic impact of a situation where no CANADA-UK TCA is in place and the U.K. is no longer part of the CETA. The United Kingdom officially left the European Union (EU) on January 31, 2020, and CETA will cease to apply to Canada–U.K. trade on January 1, 2021. To avoid a gap in preferential trade access into each other’s markets, Canada and the United Kingdom negotiated a trade continuity agreement - the CANADA- UK TCA - that provides Canadian exporters, services providers, and farmers with continued preferential access to the U.K. market carried over from CETA. CETA removed 98% of tariffs on Canadian goods and over time will remove approximately 99% of tariffs, in addition to the other CETA benefits including improved access for services, greater certainty and transparency, protection for investments and intellectual property. In the absence of CANADA-UK TCA, bilateral trade between the two countries would be governed by the World Trade Organization (WTO) rules alone, and goods trade between the United Kingdom and Canada would be subject to WTO most-favoured nation (MFN) duties. In May 2020, the United Kingdom announced the applied MFN tariffs, which it refers to as the UK Global Tariff (UKGT), that would take effect on January 1, 2021. -

The Interaction Between Ethnic Relations and State Power: a Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Georgia State University Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Sociology Dissertations Department of Sociology 5-27-2008 The nI teraction between Ethnic Relations and State Power: A Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911 Wei Li Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_diss Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Li, Wei, "The nI teraction between Ethnic Relations and State Power: A Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2008. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_diss/33 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Sociology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INTERACTION BETWEEN ETHNIC RELATIONS AND STATE POWER: A STRUCTURAL IMPEDIMENT TO THE INDUSTRIALIZATION OF CHINA, 1850-1911 by WEI LI Under the Direction of Toshi Kii ABSTRACT The case of late Qing China is of great importance to theories of economic development. This study examines the question of why China’s industrialization was slow between 1865 and 1895 as compared to contemporary Japan’s. Industrialization is measured on four dimensions: sea transport, railway, communications, and the cotton textile industry. I trace the difference between China’s and Japan’s industrialization to government leadership, which includes three aspects: direct governmental investment, government policies at the macro-level, and specific measures and actions to assist selected companies and industries. -

The Diary of a Manchu Soldier in Seventeenth-Century China: “My

THE DIARY OF A MANCHU SOLDIER IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY CHINA The Manchu conquest of China inaugurated one of the most successful and long-living dynasties in Chinese history: the Qing (1644–1911). The wars fought by the Manchus to invade China and consolidate the power of the Qing imperial house spanned over many decades through most of the seventeenth century. This book provides the first Western translation of the diary of Dzengmeo, a young Manchu officer, and recounts the events of the War of the Three Feudatories (1673–1682), fought mostly in southwestern China and widely regarded as the most serious internal military challenge faced by the Manchus before the Taiping rebellion (1851–1864). The author’s participation in the campaign provides the close-up, emotional perspective on what it meant to be in combat, while also providing a rare window into the overall organization of the Qing army, and new data in key areas of military history such as combat, armament, logistics, rank relations, and military culture. The diary represents a fine and rare example of Manchu personal writing, and shows how critical the development of Manchu studies can be for our knowledge of China’s early modern history. Nicola Di Cosmo joined the Institute for Advanced Study, School of Historical Studies, in 2003 as the Luce Foundation Professor in East Asian Studies. He is the author of Ancient China and Its Enemies (Cambridge University Press, 2002) and his research interests are in Mongol and Manchu studies and Sino-Inner Asian relations. ROUTLEDGE STUDIES -

Chinese Redemptive Societies and Salvationist Religion: Historical

Redemptive Societies: Historical Phenomenon or Sociological Category? Chinese Redemptive Societies and Salvationist Religion: Historical Phenomenon or Sociological Category? David A. Palmer Assistant Professor University of Hong Kong Dept. of Sociology and Centre for Anthropological Research1 PRE-PUBLICATION VERSION Published in Journal of Chinese Theatre, Ritual and Folklore/ Minsu Quyi 172 (2011), pp. 21-72. Abstract This paper outlines a conceptual framework for research on Chinese redemptive societies and salvationist religion. I begin with a review of past scholarship on Republican-era salvationist movements and their contemporary communities, comparing their treatment in three bodies of scholarly literature dealing with the history and scriptures of “sectarianism” in the late imperial era, the history of “secret societies” of the republican period, and the ethnography of “popular religion” in the contemporary Chinese world. I then assess Prasenjit Duara’s formulation of “redemptive societies” as a label for a constellation of religious groups active in the republican period, and, after comparing the characteristics of the main groups in question (such as the Tongshanshe, Daoyuan, Yiguandao and others), argue that an anaytical distinction needs to be made between “salvationist movements” as a sociological category, which have appeared throughout Chinese history and until today, and redemptive societies as one historical instance of a wave of salvationist movements, which appeared in the republican period and bear the imprint of the socio-cultural conditions and concerns of that period. Finally, I discuss issues for future research and the significance of redemptive societies in the social, political and intellectual history of modern China, and in the modern history of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. -

The Ming Dynasty

The East Asian World 1400–1800 Key Events As you read this chapter, look for the key events in the history of the East Asian world. • China closed its doors to the Europeans during the period of exploration between 1500 and 1800. • The Ming and Qing dynasties produced blue-and-white porcelain and new literary forms. • Emperor Yong Le began renovations on the Imperial City, which was expanded by succeeding emperors. The Impact Today The events that occurred during this time still impact our lives today. • China today exports more goods than it imports. • Chinese porcelain is collected and admired throughout the world. • The Forbidden City in China is an architectural wonder that continues to attract people from around the world. • Relations with China today still require diplomacy and skill. World History Video The Chapter 16 video, “The Samurai,” chronicles the role of the warrior class in Japanese history. 1514 Portuguese arrive in China Chinese sailing ship 1400 1435 1470 1505 1540 1575 1405 1550 Zheng He Ming dynasty begins voyages flourishes of exploration Ming dynasty porcelain bowl 482 Art or Photo here The Forbidden City in the heart of Beijing contains hundreds of buildings. 1796 1598 1644 1750 White Lotus HISTORY Japanese Last Ming Edo is one of rebellion unification emperor the world’s weakens Qing begins dies largest cities dynasty Chapter Overview Visit the Glencoe World History Web site at 1610 1645 1680 1715 1750 1785 tx.wh.glencoe.com and click on Chapter 16–Chapter Overview to preview chapter information. 1603 1661 1793 Tokugawa Emperor Britain’s King rule begins Kangxi begins George III sends “Great 61-year reign trade mission Peace” to China Japanese samurai 483 Emperor Qianlong The meeting of Emperor Qianlong and Lord George Macartney Mission to China n 1793, a British official named Lord George Macartney led a mission on behalf of King George III to China. -

The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933

The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Schluessel, Eric T. 2016. The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493602 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933 A dissertation presented by Eric Tanner Schluessel to The Committee on History and East Asian Languages in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History and East Asian Languages Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April, 2016 © 2016 – Eric Schluessel All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Mark C. Elliott Eric Tanner Schluessel The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933 Abstract This dissertation concerns the ways in which a Chinese civilizing project intervened powerfully in cultural and social change in the Muslim-majority region of Xinjiang from the 1870s through the 1930s. I demonstrate that the efforts of officials following an ideology of domination and transformation rooted in the Chinese Classics changed the ways that people associated with each other and defined themselves and how Muslims understood their place in history and in global space.