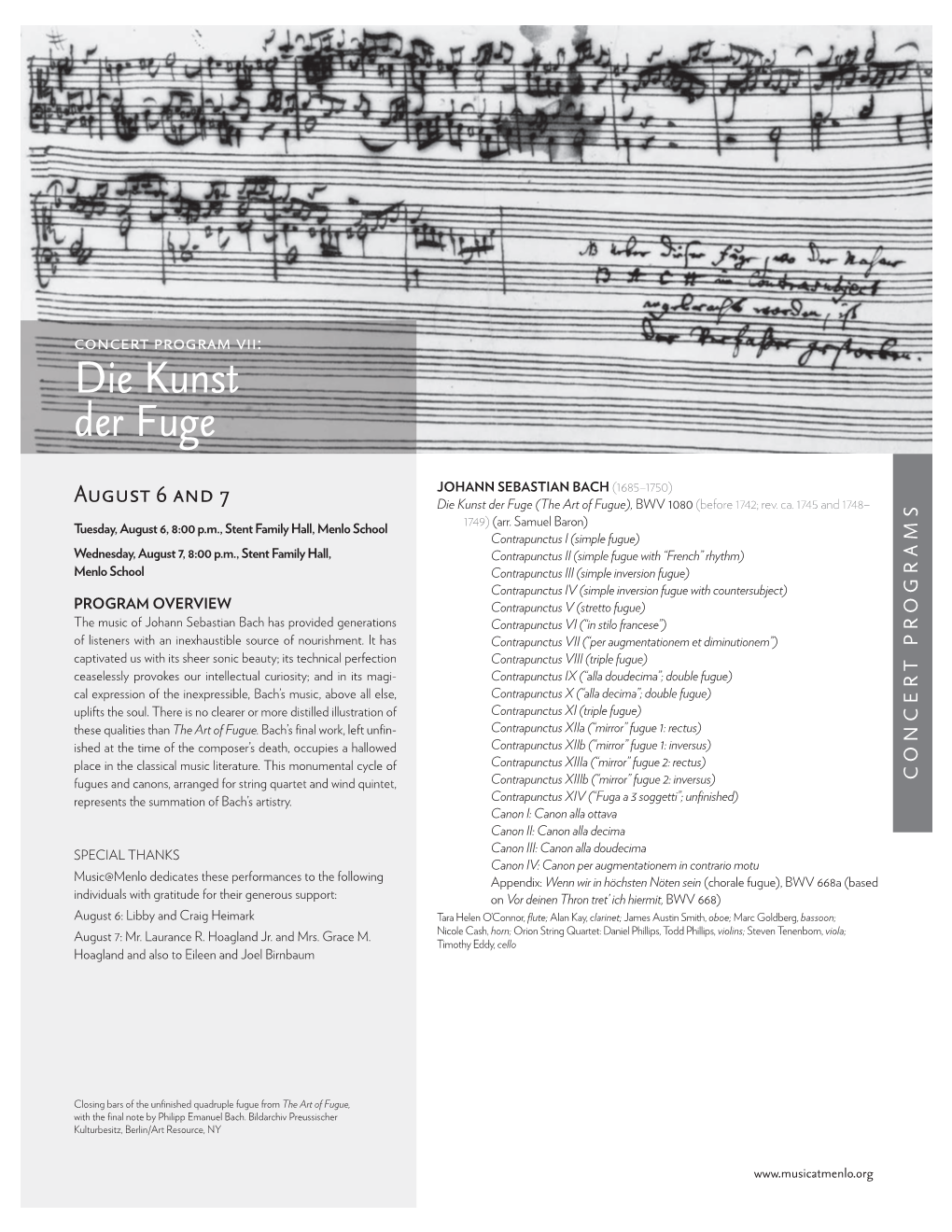

Die Kunst Der Fuge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bach Experience

MUSIC AT MARSH CHAPEL 10|11 Scott Allen Jarrett Music Director Sunday, December 12, 2010 – 9:45A.M. The Bach Experience BWV 62: ‘Nunn komm, der Heiden Heiland’ Marsh Chapel Choir and Collegium Scott Allen Jarrett, DMA, presenting General Information - Composed in Leipzig in 1724 for the first Sunday in Advent - Scored for two oboes, horn, continuo and strings; solos for soprano, alto, tenor and bass - Though celebratory as the musical start of the church year, the cantata balances the joyful anticipation of Christ’s coming with reflective gravity as depicted in Luther’s chorale - The text is based wholly on Luther’s 1524 chorale, ‘Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland.’ While the outer movements are taken directly from Luther, movements 2-5 are adaptations of the verses two through seven by an unknown librettist. - Duration: about 22 minutes Some helpful German words to know . Heiden heathen (nations) Heiland savior bewundert marvel höchste highest Beherrscher ruler Keuschheit purity nicht beflekket unblemished laufen to run streite struggle Schwachen the weak See the morning’s bulletin for a complete translation of Cantata 62. Some helpful music terms to know . Continuo – generally used in Baroque music to indicate the group of instruments who play the bass line, and thereby, establish harmony; usually includes the keyboard instrument (organ or harpsichord), and a combination of cello and bass, and sometimes bassoon. Da capo – literally means ‘from the head’ in Italian; in musical application this means to return to the beginning of the music. As a form (i.e. ‘da capo’ aria), it refers to a style in which a middle section, usually in a different tonal area or key, is followed by an restatement of the opening section: ABA. -

Introduction

Copyright © Thomas Braatz, 20071 Introduction This paper proposes to trace the origin and rather quick demise of the Andreas Stübel Theory, a theory which purportedly attempted to designate a librettist who supplied Johann Sebastian Bach with texts and worked with him when the latter composed the greater portion of the 2nd ‘chorale-cantata’ cycle in Leipzig from 1724 to early 1725. It was Hans- Joachim Schulze who first proposed this theory in 1998 after which it encountered a mixed reception with Christoph Wolff lending it some support in his Bach biography2 and in his notes for the Koopman Bach-Cantata recording series3, but with Martin Geck4 viewing it rather less enthusiastically as a theory that resembled a ball thrown onto the roulette wheel and having the same chance of winning a jackpot. 1 This document may be freely copied and distributed providing that distribution is made in full and the author’s copyright notice is retained. 2 Christoph Wolff, Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician (Norton, 2000), (first published as a paperback in 2001), p. 278. 3 Christoph Wolff, ‘The Leipzig church cantatas: the chorale cantata cycle (II:1724-1725)’ in The Complete Cantatas volumes 10 and 11 as recorded by Ton Koopman and published by Erato Disques (Paris, France, 2001). 4 Martin Geck, Bach: Leben und Werk, (Hamburg, 2000), p. 400. 1 Andreas Stübel Andreas Stübel (also known as Stiefel = ‘boot’) was born as the son of an innkeeper in Dresden on December 15, 1653. In Dresden he first attended the Latin School located there. Then, in 1668, he attended the Prince’s School (“Fürstenschule”) in Meißen. -

Ctspubs Brochure Nov 2005

THE MUSIC OF CLAUDE T. SMITH CONCERT BAND WORKS ENJOY A CD RECORDING CTS = Claude T. Smith Publications WJ = Wingert-Jones HL = Hal Leonard TITLE GRADE PUBLISHER TITLE GRADE PUBLISHER $1 OF THE MUSIC OF 7.95 each Acclamation..............................................................5 ..............Kalmus Intrada: Adoration and Praise ..................................4 ................CTS All 6 for Across the Wide Missouri (Concert Band) ................3..................WJ Introduction and Caccia............................................3 ................CTS $60 Affirmation and Credo ..............................................4 ................CTS Introduction and Fugato............................................3 ................CTS Claude T. Smith Allegheny Portrait ....................................................4 ................CTS Invocation and Jubiloso ............................................2 ..................HL Allegro and Intermezzo Overture ..............................3 ................CTS Island Fiesta ............................................................3 ................CTS America the Beautiful ..............................................2 ................CTS Joyance....................................................................5..................WJ CLAUDE T. SMITH: CLAUDE T. SMITH: American Folk Trilogy ..............................................3 ................CTS Jubilant Prelude ......................................................4 ..................HL A SYMPHONIC PORTRAIT -

MTO 19.3: Brody, Review of Matthew Dirst, Engaging Bach

Volume 19, Number 3, September 2013 Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory Review of Matthew Dirst, Engaging Bach: The Keyboard Legacy from Marpurg to Mendelssohn (Cambridge University Press, 2012) Christopher Brody KEYWORDS: Bach, Bach reception, Mozart, fugue, chorale, Well-Tempered Clavier Received July 2013 [1] Historical research on Johann Sebastian Bach entered its modern era in the late 1950s with the development, spearheaded by Alfred Dürr, Georg von Dadelsen, and Wisso Weiss, of the so-called “new chronology” of his works.(1) In parallel with this revolution, the history of the dissemination and reception of Bach was also being rewritten. Whereas Hans T. David and Arthur Mendel wrote, in 1945, that “Bach and his works ... [were] practically forgotten by the generations following his” (358), by 1998 Christoph Wolff could describe the far more nuanced understanding of Bach reception that had arisen in the intervening years in terms of “two complementary aspects”: on the one hand, the beginning of a more broadly based public reception of Bach’s music in the early nineteenth century, for which Mendelssohn’s 1829 performance of the St. Matthew Passion represents a decisive milestone; on the other hand, the uninterrupted reception of a more private kind, largely confined to circles of professional musicians, who regarded Bach’s fugues and chorales in particular as a continuing challenge, a source of inspiration, and a yardstick for measuring compositional quality. (485–86) [2] In most respects it is with the latter (though chronologically earlier) aspect that Matthew Dirst’s survey Engaging Bach: The Keyboard Legacy from Marpurg to Mendelssohn concerns itself, serving as a fine single-volume introduction to the “private” side of Bach reception up to about 1850. -

Bach: a Beautiful Mind Sun 19 Jan, Milton Court Concert Hall 2 Bach: a Beautiful Mind Sun 19 Jan, Milton Court Concert Hall Important Information Allowed in the Hall

Sun 19 Jan, Milton Court Milton Concert Jan, Hall 19 Sun Bach: A Beautiful Mind Sat 18 & Sun 19 Jan Milton Court Concert Hall Part of Barbican Presents 2019–20 Bach: A Beautiful Mind 1 Important information When does the I’m running late! Please… Sun 19 Jan, Milton Court Milton Concert Jan, Hall 19 Sun concert start Latecomers will be Switch any watch and finish? admitted if there is a alarms and mobile The first concert begins suitable break in the phones to silent during at 2pm. performance. the performance. The second concert begins at 7.30pm. Please don’t… Use a hearing aid? Need a break? Take photos or Please use our induction You can leave at any recordings during the loop – just switch your time and be readmitted if performance – save it hearing aid to T setting there is a suitable break for the curtain call. on entering the hall. in the performance, or during the interval. Looking for Looking for Carrying bags refreshment? the toilets? and coats? Bars are located on The nearest toilets, Drop them off at our free Levels 1 and 2. Pre-order including accessible cloak room on Level -1. interval drinks to beat the toilets, are located on the queues. Drinks are not Ground Floor and Level Bach: A Beautiful Mind allowed in the hall. 2. There are accessible toilets on every level. 2 Welcome to today’s performances Today sees the concluding part of Accademia Bizantina under its director Bach: A Beautiful Mind, our weekend Ottavio Dantone. exploring the multi-faceted genius of The final concert celebrates Bach’s J S Bach, curated by Mahan Esfahani. -

The Neumeister Collection of Chorale Preludes of the Bach Circle: an Examination of the Chorale Preludes of J

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 "The eumeiN ster collection of chorale preludes of the Bach circle": an examination of the chorale preludes of J. S. Bach and their usage as service music and pedagogical works Sara Ann Jones Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Sara Ann, ""The eN umeister collection of chorale preludes of the Bach circle": an examination of the chorale preludes of J. S. Bach and their usage as service music and pedagogical works" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 77. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/77 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE NEUMEISTER COLLECTION OF CHORALE PRELUDES OF THE BACH CIRCLE: AN EXAMINATION OF THE CHORALE PRELUDES OF J. S. BACH AND THEIR USAGE AS SERVICE MUSIC AND PEDAGOGICAL WORKS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music and Dramatic Arts Sara Ann Jones B. A., McNeese State University -

Rethinking J.S. Bach's Musical Offering

Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering By Anatoly Milka Translated from Russian by Marina Ritzarev Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering By Anatoly Milka Translated from Russian by Marina Ritzarev This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Anatoly Milka All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-3706-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-3706-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... vii List of Schemes ....................................................................................... viii List of Music Examples .............................................................................. x List of Tables ............................................................................................ xii List of Abbreviations ............................................................................... xiii Preface ...................................................................................................... xv Introduction ............................................................................................... -

The Treatment of the Chorale Wie Scan Leuchtet Der Iorgenstern in Organ Compositions from the Seven Teenth Century to the Twentieth Century

379 THE TREATMENT OF THE CHORALE WIE SCAN LEUCHTET DER IORGENSTERN IN ORGAN COMPOSITIONS FROM THE SEVEN TEENTH CENTURY TO THE TWENTIETH CENTURY THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Paul Winston Renick, B. M. Denton, Texas August, 1961 PREFACE The chorale Wie schn iihtet derMorgenstern was popular from its very outset in 1589. That it has retained its popularity down to the present day is evident by its continually appearing in hymnbooks and being used as a cantus in organ compositions as well as forming the basis for other media of musical composition. The treatment of organ compositions based on this single chorale not only exemplifies the curiously novel attraction that this tune has held for composers, but also supplies a common denominator by which the history of the organ chorale can be generally stated. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE . * . * . * . * * * . * . LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . .0.0..0... 0 .0. .. V Chapter I. THE LUTHERAN CHORALE. .. .. The Development of the Chorale up to Bach The Chorale Wie sch8n leuchtet der Morgenstern II. BEGINNINGS OF THE ORGAN CHORALE . .14 III* ORGAN CHORALS BASED ON WIE SCHN IN THE BAROQUE ERA .. *. .. * . .. 25 Samuel Scheidt Dietrich Buxtehude Johann Christoph Bach Johann Pachelbel Johann Heinrich Buttstet Andreas Armsdorf J. S. Bach IV. ORGAN COMPOSITIONS BASED ON WIE SCHON ...... 42 AFTER BACH . 4 Johann Christian Rinck Max Reger Sigf rid Karg-Elert Heinrich Kaminsky Ernst Pepping Johann Nepomuk David Flor Peeters and Garth Edmund son V. -

'Modern Baroque'

‘Modern Baroque’ ‘Approaches and Attitudes to Baroque Music Performance on the Saxophone’ Jonathan Byrnes 4080160 Masters of Music Projecto Cientifico IV ESMAE 2010 1 Contents Page ‘Introduction’ (Prelude) 4 ‘Education’ (Allemande) 7 ‘Performance’ (Courante) 12 ‘Morality – Responsibility and Reasons.’ (Sarabande) 18 ‘Transcription or adaptation’ – note for note transcription (Minuet I) 36 ‘Transcription or adaptation’ – adaptation (Minuet II) 58 Conclusion (Gigue) 70 ‘Bibliography’ 73 ‘Discography’ 77 ‘Internet Resourses’ 78 2 Thank you. This Masters Thesis would not have been possible without the help and assistance from the people below. I would like to thank them sincerely for all their guidence and support. Sofia Lourenço, Henk Van Twillert, Fernando Ramos, Gilberto Bernardes, Madelena Soveral, Dr. Cecília, Filipe Fonseca, Luís Lima, Nicholas Russoniello, Cláudio Dioguardi, Cármen Nieves, Alexander Brito, Donny McKenzie, Andy Harper, Thom Chapman, Alana Blackburn, Paul Leenhouts, Harry White, And of course my family. Without these people, I am sure I would not have achieved this work. 3 1. Introduction (Prelude) Baroque music has been part of the saxophone repertoire in one form or another since the instruments creation, as it so happened to coincide with the Baroque revival. ‘It was Mendelssohn's promotion of the St Matthew Passion in 1829 which marked the first public "revival" of Bach and his music’ 1, either through studies or repertoire the music of the baroque period has had an important role in the development of the majority of all saxophonists today. However the question remains. What function does this music have for a modern instrumentalist and how should this music be used or performed by a saxophonist? Many accolades have been given of saxophone performances of Baroque music. -

The Bach Experience

MUSIC AT MARSH CHAPEL 10|11 Scott Allen Jarrett Music Director Sunday, January 30, 2011 – 9:45A.M. The Bach Experience BWV 171: ‘Gott, wie dein Name, so ist auch dein Ruhm’ Marsh Chapel Choir and Collegium Scott Allen Jarrett, DMA, presenting BWV 171: ‘Gott, wie dein Name, so ist auch dein Ruhm’ - Composed and performed as early as January 1, 1729 for New Year or Feast of the Circumcision; first movement appears later in the Credo of the B Minor Mass: ‘Patrem omnipotentem’ - Scored for three trumpets, timpani, two oboes, and strings; solos for soprano, alto, tenor and bass - Central message is the name of Christ – the purity of Jesus’ name as a means of intercession, power and strength - The libretto is compiled and authored by Picander, drawing on Psalm 48:10 for the opening movement. - Duration: about 21 minutes Some helpful German words to know . Ruhm fame Wolken clouds Süsser sweet Trost comfort Ruh rest or peace Kreuze cross lauf laugh verfolget persecuted Heliand savior See the morning’s bulletin for a complete translation of Cantata 171. Some helpful music terms to know . Continuo – generally used in Baroque music to indicate the group of instruments who play the bass line, and thereby, establish harmony; usually includes the keyboard instrument (organ or harpsichord), and a combination of cello and bass, and sometimes bassoon. Da capo – literally means ‘the head’ in Italian; in musical application this means to return to the beginning of the music. As a form (i.e. ‘da capo’ aria), it refers to a style in which a middle section, usually in a different tonal area or key, is followed by an exact restatement of the opening section: ABA. -

10.-Baroque-J.S.Bach.Pdf

The HIGH BAROQUE:! J. S. BACH Johann Sebastian Bach, 1685-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! J. S. BACH J. S. BACH was best-known during his lifetime as a keyboard virtuoso Born into family of musicians. Lives a provincial life, never traveling out of Germany The youngest of eight children, Bach was educated by his brother, Johann Christoph. The HIGH BAROQUE:! J. S. BACH CAREER Arnstadt 1707 Organist Weimar 1708-1717 Organist, Konzertmeister Cöthen 1717-1723 Kapellmeister Leipzig 1723- Kapellmeister, Teacher The HIGH BAROQUE:! J. S. BACH Bach wrote in almost ALL the genres of music in the late Baroque EXCEPT the most important of that era, OPERA. Bach tended to write in sets of compositions, systematically pursuing the invention of an idea, elaborating it through every possible permutation. The HIGH BAROQUE:! J. S. BACH Bach’s compositions spring from his jobs: Many secular compositions for his court positions at WEIMAR and CöTHEN, and religious music for his later position at LEIPZIG. As a virtuoso keyboardist, Bach writes keyboard music through out his life. The HIGH BAROQUE:! J. S. BACH 1707 Bach obtains his first position of organist at the Arnstadt Neukirche. Obtains permission to travel Lübeck to hear the organist Buxtehude… and stays away for 4 months! The HIGH BAROQUE:! J. S. BACH 1708-1717 (Weimar) Position at court of Weimar, first as organist, and then as Konzertmeister in 1714. During his Weimar years Bach gets to know G. P. TELEMANN, who is working nearby in Eisenach. Bach marries Maria Barbara who has his first children. The HIGH BAROQUE:! J. -

ONW Choirs! Spending Time with Her Husband and Family

About the Students About the Director Pamela Williamson is the Olathe Northwest choir students are a wonderful Choral Music Director at representation of the diverse student body as a Olathe Northwest High whole. Students are talented, friendly, positive, School. Pam has been a and there is a spirit of teamwork present in our music educator in Kansas daily rehearsals and performances. Throughout public schools for over 28 our school history, ONW Choirs have consistent- years, and has been at ly earned superior (1) ratings at State Large ONW since 2006, where Group Contest, and Regional and State Solo and she is also the Performing Ensemble Festivals. We have also had a large Arts Department Chair. Under her leadership, the number of students earn places in the KMEA ONW Choirs have consistently earned superior Northwest District and Kansas Statewide Honor ratings at Regional and State Music festivals and Choirs. With more than 200 students in our cho- contests. The ONW Da Capo Singers were ral program, there are many things happening selected by audition to perform at the 2011 KMEA that we encourage you to become involved in! Statewide In-service Workshop. Students in Mrs. Welcome to Williamson’ program have performed with Kansas District and Statewide Honor Choirs, SWACDA and National ACDA Honor Choirs, with the Kansas City Chorale and the Kansas City Symphony. The Olathe Northwest choirs earned the top award at Festival Disney as ‘Best in Show” in 2010 and First Place in their division in Orlando, Florida where they also earned Raven Choral Superior ratings in 2016. Our choir earned Superior Musical Performance and Outstanding in Class Music awards at the 2013 Alamo Showcase of Music Festival in San Antonio, Texas.