Wilson's Creek National Battlefield Geologic Resources Inventory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pennsylvanian Crinoids of New Mexico

Pennsylvanian crinoids of New Mexico Gary D. Webster, Department of Geology, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164, and Barry S. Kues, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131 Abstract north of Alamogordo; (2) Morrowan and groups present on the outcrop were sam- Atokan specimens from the La Pasada For- pled, often repeatedly over the years. Crinoids from each of the five Pennsylvanian mation in the Santa Fe area; and (3) a mid- These collections, reposited at the Univer- epochs are described from 26 localities in dle Desmoinesian species from the Alami- sity of New Mexico (UNM), testify to the New Mexico. The crinoid faunas occupied tos Formation, north of Pecos. Bowsher rarity of identifiable crinoid cups and diverse shelf environments around many intermontane basins of New Mexico during and Strimple (1986) described 15 late crowns in these assemblages, even in cases the Pennsylvanian. The crinoids described Desmoinesian or early Missourian crinoid where crinoid stem elements are common. here include 29 genera, 39 named species, species (several not named) from near the In nearly all collections, crinoid cups rep- and at least nine unnamed species, of which top of the Bug Scuffle Member of the Gob- resent only a small fraction of 1% of the one genus and 15 named species are new. bler Formation south of Alamogordo in the total identifiable specimens. The only This report more than doubles the number of Sacramento Mountains. Kietzke (1990) exception is the fauna from the Missourian previously known Pennsylvanian crinoid illustrated a Desmoinesian microcrinoid Sol se Mete Member, Wild Cow Formation, species from New Mexico; 17 of these species from the Flechado Formation near Talpa. -

Some Crinoids from the Argentine Limestone (Late Pennsylvania- Missourian) of Southeastern Nebraska and Southwestern Iowa

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societies Nebraska Academy of Sciences 1980 Some Crinoids from the Argentine Limestone (Late Pennsylvania- Missourian) of Southeastern Nebraska and Southwestern Iowa Roger K. Pabian University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Harrell L. Strimple University of Iowa Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tnas Part of the Life Sciences Commons Pabian, Roger K. and Strimple, Harrell L., "Some Crinoids from the Argentine Limestone (Late Pennsylvania-Missourian) of Southeastern Nebraska and Southwestern Iowa" (1980). Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societies. 288. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tnas/288 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nebraska Academy of Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societiesy b an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1980. Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences, VIII: 155-186. SOME CRINOIDS FROM THE ARGENTINE LIMESTONE (LATE PENNSYLVANIAN-MISSOURIAN) OF SOUTHEASTERN NEBRASKA AND SOUTHWESTERN IOWA Roger K. Pabian and Harrell L. Strimple Conservation and Survey Division, Department of Geology Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources University of Iowa University of Nebraska-Lincoln Iowa City, Iowa 52242 Lincoln, Nebraska 68588 Familial diversity of crinoids is relatively constant throughout positions in cyclothems or to provide ecological interpreta the Missourian Series of southeastern Nebraska and southwestern Iowa. tions based on cyclothemic models sensu Heckel and Baese Beginning with the deposition of the Argentine Limestone, there ap mann (1975), or Heckel (1977). -

Xerox University Microfiims

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they a e spiiced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complote continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corrser of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority o f users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Paleontological Contributions

THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS PALEONTOLOGICAL CONTRIBUTIONS November 24, 1971 Paper 56 FOSSIL CRINOID STUDIES HARRELL L. STRIMPLE, RAYMOND C. MOORE, RICHARD C. ALLISON, GARY L. KLINE, A. S. HOROWITZ, D. R. BOARDMAN II, and JAMES F. MILLER CONTENTS PAGE PART I. THE FAMILY DIPHUICRINIDAE (Harrell L. Strimple, Raymond C. Moore) 2 PART 2. PENNSYLVANIAN CRINOIDS FROM ALASKA (Harrell L. Strimple, Richard C. Allison, Gary L. Kline) 9 PART 3. THE OCCURRENCE OF HYDRIOCRINUS IN OKLAHOMA AND RUSSIA (Harrell L. Strimple) . 16 PART 4. NOTES ON DELOCRINUS AND ENDELOCRINUS FROM THE LANE SHALE (MISSOURIAN) OF KANSAS CITY (Harrell L. Strimple, Raymond C. Moore) 19 PART 5. A NEW MISSISSIPPIAN AMPELOCRINID (Harrell L. Strimple, A. S. Horowitz) 23 PART 6. NOTES ON STENOPECRINUS AND PERIMESTOCRINUS (Harrell L. Strimple, D. R. Boardman II) 27 PART 7. AGNOSTOCRINUS FROM THE UPPER PERMIAN OF TEXAS (Harrell L. Strimple) 31 PART 8. A CRINOID CROWN FROM D ' ORBIGNY ' S FAMOUS FOSSIL LOCALITY AT YAURICHAMPI, BOLIVIA (Harrell L. Strimple, Raymond C. Moore) 33 PART 9. PENNSYLVANIAN CRINOIDS FROM THE PINKERTON TRAIL LIMESTONE, MOLAS LAKE, COLORADO (Harrell L. Strimple, James F. Miller) 35 2 The University of Kansas Paleontological Contributions—Paper 56 PART 1 THE FAMILY DIPHUICRINIDAE HARRELL L. STRIMPLE and RAYMOND C. MOORE The University of Iowa, Iowa City; The University of Kansas, Lawrence ABSTRACT The present study is for the purpose of stabilizing the family Diphuicrinidae STRIMPLE & KNAPP, 1966. The lineage is first known from the Bloyd Formation, Lower Pennsyl- vanian (Morrowan), of Oklahoma and Arkansas. Parallelocrinus KNAPP, 1969, from the Burgner Formation, Lower Pennsylvanian (Atokan), of Missouri, is placed in synonymy with Diphuicrinus MOORE & PLUMMER. -

A Handbook of the Invertebrate Fossils of Nebraska

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Conservation and Survey Division Natural Resources, School of 6-1970 Record in Rock: A Handbook of the Invertebrate Fossils of Nebraska Roger K. Pabian University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/conservationsurvey Part of the Natural Resources and Conservation Commons Pabian, Roger K., "Record in Rock: A Handbook of the Invertebrate Fossils of Nebraska" (1970). Conservation and Survey Division. 1. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/conservationsurvey/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Natural Resources, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Conservation and Survey Division by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A Handbook of the Invertebrate Fossils of Nebraska /} / ~>,\\1 ' 6fJ By ) ROGER K. PABIAN \ \ I t ~ <-' ) \!\. \/ \J... Illustrated By , n ~ SALLY LYNNE HEALD f.1 I EDUCATIONAL CIRCULAR No.1 ( NIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA-CONSERVATION AND SURVEY DIVISION \ f / / EDUCATIONAL CIRCULAR NUMBER 1 JUNE 1970 RECORD IN ROCK A Hamlbook of the Invertebrate Fossils of Nebraska By ROGER K. PABIAN Illustrated By SALLY LYNNE HEALD PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA CONSERVATION AND SURVEY DIVISION, LINCOLN THE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA DURWARD B. VARNER, Chancellor JOSEPH SOSHNIK, President, Lincoln Campuses and Outstate Activities BOARD OF REGENTS ROBERT RAUN, Minden, Pres. J. G. ELLIOTT, Scottsbluff B. N. GREENBERG, M.D., York, Vice Pres. RICHARD HERMAN, Omaha RICHARD ADKINS, Osmond EDWARD SCHWARTZKOPF, Lincoln CONSERVATION AND SURVEY DIVISION V. H. DREESZEN, Director and State Geologist M. -

The Structure, Classification and Arrange Ment Of

THE STRUCTURE, CLASSIFICATION AND ARRANGE MENT OF AMEqlCAN PAL;£OZOIC CRINOIDS INTO FAMILIES. BY S. A. MILLER. There have been described from North American Palreozoic rocks 1,100 species of crinoids, which are referred to about 110 genera. The arrange ment of these genera into families, based upon uniform and consistent rules, is· the object of this article. 'Vhen I published my work on North American Geology and Palreon tology I proposed a few new family names, but as my object then was to present the state of tlie science as it existed, and not to write an original treatise on anyone branch, I generally followed the classification of others, and as they were not in accord as to family characters, the families as there given are not of equal value. The new family names which I pro posed were not defined and hence were used only provisionally, and be cause I could not refer the genera to families that had been limited and defined. Indeed, I did nothavc the time to properly classify the genera into families nor access to the fossils for the purpose of verifying such classification if I had taken the time from other duties. Since that work was done 1 have had an opportunity to inspect a large lot of crinoids from Mr. Gurley's collection, in addition to those in my own cabinet, and to review the various systems of classification in use .in this country, and now propose to present my views of family classification. I would desire to state, in the first place, that, in many instances. -

Endelocrinus Kieri, a New Crinoid from the Ames Limestone1

ENDELOCRINUS KIERI, A NEW CRINOID FROM THE AMES LIMESTONE1 J. J. BURKE2 Ohio Division of Geological Survey, Columbus, Ohio ABSTRACT A new species of cladoid inadunate crinoid, Endelocrinus kieri sp. n. from the Ames Limestone, Conemaugh Group, Pennsylvanian, is described. The Conemaugh form is closely related to Endelocrinus rectus Moore and Plummer from the Strawn Group of Texas, although more specialized than the Texas species. The retention of ornamented species in Endelocrinus is advocated. The validity of the Strimple genera Tholiacrinus and Graffhamicrinus, which are based on surface ornamentation, is questioned. The new species of Endelocrinus described in the following pages is based on specimens collected from the Ames Limestone, Conemaugh Group, Pennsylvanian, in Guernsey County, Ohio, and in Brooke County, West Virginia. The type material shows growth stages and variations that are pertinent to an understanding of Endelocrinus in general, and because the species is more specialized than the related Endelocrinus rectus Moore and Plummer of Desmoinesian age, it may prove of value in stratigraphic correlation. I am indebted to Dr. E. R. Eller of the Carnegie Museum and Mr. Thomas J. M. Schopf of the Orton Museum of the Ohio State University for the loan of crinoid material to supplement this study. Dr. Porter M. Kier of the United States National Museum, for whom this new species is named, has been especially kind in permitting me to have access to the crinoid collections of that institution during my visits to Washington. I also wish to thank Mr. Calvin Colson of Ohio University, for making the photographs from which the illustrations were prepared. -

Download Link

THE GEOLOGICAL CURATOR VOLUME 7, NO. 10 & INDEX VOLUME 7, NUMBERS 1–10 CONTENTS SOME EARLY COLLECTORS AND COLLECTIONS OF FOSSIL SPONGES REPRESENTED IN THE NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM, LONDON by S.L. Long, P.D. Taylor, S. Baker and J. Cooper....................................................................................................353 COMMENT ON ‘TYPE AND FIGURED SPECIMENS IN THE GEOLOGY MUSEUM, UNIVERSITY OF THE WEST INDIES, MONA CAMPUS, JAMAICA’ by S.K. Donovan.....................................................................................................................................................363 CURATION OF PALYNOLOGICAL MATERIAL: A CASE STUDY ON THE BRITISH PETROLEUM MICROPALAEONTOLOGICAL COLLECTION by J. Dunn........................................................................................................................................................365 UPPER CARBONIFEROUS CRINOIDS: AN EXTRAORDINARY COLLECTION BY LATE 19TH CENTURY AMATEUR PALAEONTOLOGISTS, KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI, U.S.A. by R.J. Gentile........................................................................................................................................................373 JOHN NORTON 1924–2002: AN APPRECIATION by P. Toghill........................................................................................................................................................381 LOST & FOUND.......................................................................................................................................................383 -

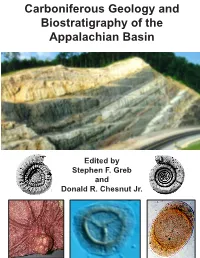

Carboniferous Geology and Biostratigraphy of the Appalachian Basin

Carboniferous Geology and Biostratigraphy of the Appalachian Basin Edited by Stephen F. Greb and Donald R. Chesnut Jr. Kentucky Geological Survey James C. Cobb, State Geologist and Director University of Kentucky, Lexington Carboniferous of the Appalachian and Black Warrior Basins Edited by Stephen F. Greb and Donald R. Chesnut Jr. Special Publication 10 Series XII, 2009 Our Mission Our mission is to increase knowledge and understanding of the mineral, energy, and water resources, geologic hazards, and geology of Kentucky for the benefit of the Commonwealth and Nation. Earth Resources—Our Common Wealth www.uky.edu/kgs Technical Level General Intermediate Technical © 2009 University of Kentucky For further information contact: Technology Transfer Officer Kentucky Geological Survey 228 Mining and Mineral Resources Building University of Kentucky Lexington, KY 40506-0107 ISSN 0075-5613 Contents Foreward ...................................................................................................................................................................1 1: Introduction Donald R. Chesnut Jr. and Stephen F. Greb ............................................................................................3 2: Carboniferous of the Black Warrior Basin Jack C. Pashin and Robert A. Gastaldo ..................................................................................................10 3: The Mississippian of the Appalachian Basin Frank R. Ettensohn ....................................................................................................................................22 -

Atokan Crinoids

Oklahoma Geological Survey Bulletin 1.16, 1984 ATOKAN CRINOIDS H. L. STRIMPLEl Abstract-Articulated crinoids are not as prolific in the Atokan Stage as they are in the younger Desmoinesian; however, the Atokan crinoids appear to have closer affinities with them ~han with crinoids of the preceding Morrowan Stage. Conditions for the establishment of widespread "gardens" or "colonies," or for their preservation, were relatively rare in the At~kan. The largest faunas are from the Llano Uplift in north-central Texas, from southwestern MISSOUri, and from Coal County in south-central Oklahoma. Sporadic and limited occurrences of Atokan crinoids are now known from Alaska, northwest ern Spain, northern China, Ellesmere Island (Canadian Arctic), eastern Kentucky, Colorado, and New Mexico. Some species reported by Termier and Termier from Morocco are probably of Atokan age, although they are not so recorded. In addition, crinoids from Algeria and the Island of Crete are under study. INTRODUCTION and Watkins (1969, p. 150) noted the genera in a large crinoid fauna from the Atoka Formation of Conditions were seldom favorable for the pres Coal County, Oklahoma, but systematic de ervation of crinoids during the Atokan. The first scriptions were not made until later (Strimple, Atokan crinoids appear to have been described by 1975). Tien (1924, 19261, from the Houkou Limestone, Several important occurrences of Atokan cri Taiyuan Series of north China (age assignment noids have been reported since 1969. Webster and suggested by Strimple and Watkins, 19691. Lane (1970) reported the occurrence of the camer Laudon (1937) described a crown of a flexible cri ate crinoid Platycrinites sp., based on dis noid with a poorly preserved cup from the Bost articulated segments, and described two species of wick Formation of Love County, Oklahoma, which inadunate crinoids from the Atokan part of the he named Synerocrinus farishi. -

Classification, Paleoecology, and Biostratigraphy of Crinoids from the Stull Shale (Late Pennsylvanian) of Nebraska, Kansas, and Iowa Roger K

BULLETIN OF VOLUME 11, NUMBER 1 The University 0/ Nebraska State Museum MARCH,1985 Roger K. Pabian and Harrell L. Strimple Classification, Paleoecology, and Biostratigraphy of Crinoids from the Stull Shale (Late Pennsylvanian) of Nebraska, Kansas, and Iowa Roger K. Pabian and Harrell L. Strimple Classification, Paleoecology, and Biostratigraphy of Crinoids from the Stull Shale (Late Pennsylvanian) of Nebraska, Kansas, and Iowa BULLETIN OF The University of Nebraska State Museum VOLUME 11, NUMBER 1 MARCH,1985 Copyright © 1985 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska Library of Congress Catalog Card Number ISSN 0093-6812 Manufactured in the United States of America BULLETIN OF VOLUME 11, NUMBER 1 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA STATE MUSEUM March,1985 Pg. 1-81, Tables 1-20 Figs. 1-27 Abstract Classification, Paleoecology, and Biostratigraphy of Crinoids from the Stull Shale (Late Pennsylvanian) of Nebraska, Kansas, and Iowa Roger K. Pabian and Harrell L. Strimple Thirteen species of crinoids representing the families Diphuicrinidae, catacrinidae, Pirasocrinidae, Erisocrinidae, Cromyocrinidae, Cymbiocrinidae, Scytalocrinidae, and Ampelocrinidae have been collected from the Stull Shale Member of the Kanwaka Formation in the Shawnee Group of the Virgil Series (Upper Pennsylvanian) from near Weeping Water and Plattsmouth, Nebraska, and near Pacific Junction, Iowa. Exposures of the Stull Shale near Melvern, Kansas, have yielded 14 species of crinoids representing the families Diphuicrinidae, Catacrinidae, Pirasocrinidae, Lophocrinidae Allagecrinidae, Cymbiocrinidae, Erisocrinidae, Apographiocrinidae, and Stella rocrinidae. All but two of the species present in the Stull Shale have been previously reported from other stratigraphic horizons, including the Vinland Shale in Kansas, the lola and Winterset Limestones in Kansas, the Plattsburg, Oread, and Lecompton Formations of Nebraska and Iowa, the Kanawa Formation of Oklahoma, the Harpersville, Brad, and Mineral Wells Formations of Texas. -

Carboniferous Echinoderm Zonation in the Appalachian Basin, Eastern USA

Wong, Th. E. (Ed.): Proceedings of the XVth International Congress on Carboniferous and Permian Stratigraphy. Utrecht, the Netherlands, 10–16 August 2003. Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Carboniferous echinoderm zonation in the Appalachian Basin, eastern USA F.R. Ettensohn 1,W.I.Ausich2,T.W.Kammer3, W.K. Johnson 1 & D.R. Chesnut, Jr. 4 1 Department of Earth & Environmental Sciences, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40506, USA; e-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Geological Sciences, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA 3 Department of Geology and Geography, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV 26506, USA 4 Kentucky Geological Survey, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40506, USA Abstract The Carboniferous was a period of major echinoderm evolution, especially during Mississippian (Early Car- boniferous) time when crinoids, blastoids, and echinoids increased dramatically in abundance and diversity. The high degree of structural organization and distinctive morphologies of echinoderms make them ideal zonal indicators, and for parts of the Appalachian Basin Mississippian section, they provide greater biostratigraphic resolution than do conodonts or foraminifera. The occurrence of various echinoderm groups in time and space, however, is clearly related to the tectonic and sedimentologic differentiation of the Appalachian Basin through time. By Early Mississippian time on the Laurussian continent, most echinoderms had already made the shift to clastic-rich environments, which predominated in the basin until Middle Mississippian time. Although present, well-preserved Kinderhookian, Osagean, and Meramecian echinoderms are rare in the Appalachian Basin, and most are endemic forms with little diagnostic value. Echinoderms did, however, become especially abundant in the succeeding, late Middle and early Late Mississippian (Late Meramecian–Middle Chesterian), carbonate-rich seas, and it is for this time interval that biostratigraphic resolution, based especially on crinoids and blastoids, is best.