Stores and Services in Bridgewater, 1900-1910 Benjamin A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bossier City-Parish Metropolitan Planning Commission

** APPLICANT OR REPRESENTATIVE MUST BE PRESENT AT THE MPC MEETING ** BOSSIER CITY-PARISH METROPOLITAN PLANNING COMMISSION PUBLIC HEARING AND PRELIMINARY HEARING – AGENDA MONDAY, JANUARY 9, 2017, 2:00 P.M. CITY COUNCIL CHAMBERS, BOSSIER CITY HALL 620 BENTON ROAD, BOSSIER CITY, LOUISIANA A. ROLL CALL B. APPROVE AGENDA C. PUBLIC HEARING/ ACTION 1. C-75-16 - The application of Ashe Broussard Weinzettle Architects, LLP for a Conditional Use Approval for a Parking Reduction and Reduction of Landscape Buffer for Cypress Point Nursing and Rehabilitation Center, a certain tract of land located in the Northeast Corner of Airline Drive and Wemple Road, Bossier Parish, Louisiana. 2. C-82-16 - The application of Mohr and Associates for a Minor Plat, Jeanette Place, Unit No. 4, Bossier City, Louisiana. 3. C-59-16 - The application of DG Louisiana dba Dollar General Store #4749 for a Conditional Use Approval for the sale of high and low content alcohol for off-premise consumption at a Dollar General Store located at 1310 Swan Lake Road, Bossier City, Louisiana. 4. C-56-16 – The application of DG Louisiana dba Dollar General Store #10632 for a Conditional Use Approval for the sale of high and low content alcohol for off-premise consumption at a Dollar General Store located at 2100 Stockwell Road, Bossier City, Louisiana. Bossier Planning Commission Agenda January 9, 2017 Page 2 5. C-58-16 - The application of DG Louisiana dba Dollar General Store #4748 for a Conditional Use Approval for the sale of high and low content alcohol for off-premise consumption at a Dollar General Store located at 2314 Barksdale Boulevard, Bossier City, Louisiana. -

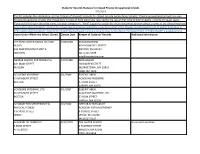

Students' Records Statuses for Closed Private Occupational Schools 7/2

Students' Records Statuses for Closed Private Occupational Schools 7/2/2019 This list includes the information on the statuses of students' records for closed, private occupational schools. Private occupational schools are non- Private occupational schools that closed prior to August 2012 were only required by the law at that time to hold students' records for seven years; If you don't find your school by name, use your computer's "Find" feature to search the entire document by your school's name as the school may have Information about students' records for closed degree-granting institutions may be located at the Massachusetts Department of Higher Education is Information about students' records for closed hospital-based nursing programs may be located at the Department of Public Health is available here. Name Under Which the School Closed Closure Date Keeper of Students' Records Additional Information 7TH ROW CENTER HANDS-ON! CAR 7/28/2008 KEVAN BUDROW AUDIO 60 BLOOMFIELD STREET 325 NEW BOSTON ST UNIT 6 BOSTON, MA 02124 WOBURN (617) 265-6939 [email protected] ABARAE SCHOOL FOR MODELING 4/20/1990 DIDA HAGAN 442 MAIN STREET 18 WARREN STREET MALDEN GEORGETOWN, MA 01833 (508) 352-7200 ACADEMIE MODERNE 4/1/1989 EILEEN T ABEN 45 NEWBURY STREET ACADEMIE MODERNE BOSTON 57 BOW STREET CARVER, MA 02339 ACADEMIE MODERNE, LTD. 4/1/1987 EILEEN T ABEN 45 NEWBURY STREET ACADEMIE MODERNE, LTD. BOSTON 57 BOW STREET CARVER, MA 02339 ACADEMY FOR MYOTHERAPY & 6/9/1989 ARTHUR SCHMALBACH PHYSICAL FITNESS ACADEMY FOR MYOTHERAPY 9 SCHOOL STREET 9 SCHOOL STREET LENOX LENOX, MA 01240 (413) 637-0317 ACADEMY OF LEARNING 9/30/2003 THE SALTER SCHOOL No records available. -

Downtown Crossing 19-21 School Street, Boston, MA 02108 Space for Lease

Downtown Crossing 19-21 School Street, Boston, MA 02108 Space for Lease DESCRIPTION n 8,131 SF available for lease n Located across from Boston’s 24,000 SF Walgreens, within blocks of Millennium Tower, the Paramount Theater, Boston Opera House n Three-story (plus basement) building located and the Omni Parker House Hotel on School Street near the intersection of Washington Street on the Freedom Trail in Boston’s Downtown Crossing retail corridor n Area retailers: Roche Bobois, Loews Theatre, Macy’s, Staples, Eddie Bauer Outlet, Gap Outlet; The Merchant, Salvatore’s, Teatro, GEM, n Exceptional opportunity for new flagship location Papagayo, MAST’, Latitude 360, Pret A Manger restaurants; Boston Common Coffee Co. and Barry’s Bootcamp n Two blocks from three MBTA stations - Park Street, Downtown Crossing and State Street FOR MORE INFORMATION Jenny Hart, [email protected], 617.369.5910 Lindsey Sandell, [email protected], 617.369.5936 351 Newbury Street | Boston, MA 02115 | F 617.262.1806 www.dartco.com 19-21 School Street, Boston, MA Cambridge East Boston INTERSTATE 49593 North End 1 N Beacon Hill Charles River SITE Financial W E District Boston Common INTERSTATE S 49593 INTERSTATE 49590 Seaport District INTERSTATE Chinatown 49590 1 SITE DATA n Located in the Downtown Crossing Washington Street Shopping District n 35 million SF of office space within the Downtown Crossing District n Office population within 1/2 mile: 190,555 n 2 blocks from the Financial District with approximately 50 million SF of office space DEMOGRAPHICS Residential Average -

A Geotourism Analysis in Spring Green, Wisconsin

Jennifer Reece Maggie Strassman Sara Dorsey Mike Kenyon Creativity Shining Through: A Geotourism Analysis in Spring Green, Wisconsin Introduction Canoeing down the Lowe Wisconsin River, paddlers encounter a variety ofthe state's natural and cultural wonders; blue herons stepping through marshes, rolling bluffs set against the open sky, and local residents casting lines off wooden docks. Our group's research interests span the discipline of geography, linking people with environment and evaluating ways in which they use their space, much like a paddler observes his or her surroundings. Our particular interests include sustainable tourism, working to provide incentives to protect natural areas, encouraging a vested interest in conserving biodiversity, urban parks and green space, and ecotourism as a form of community development. Combining our interests, we analyzed geotourism in Spring Green, as defined by National Geographic's Center for Sustainable Destinations, a forerunner in the emerging field ofgeotourism. Our research and conclusions are valuable to the Spring Green community, whose motto is "Creativity Shining Through" because they shed light on the impact ofthe area's tourist industry. The geotourism industry is a phenomenon generally applied to international or well-known places. However, we feel this project is an interesting complement to existing research, as well as our personal research endeavors. Literature Review Geotourism was first introduced as an idea in 2002 by National Geographic Traveler Magazine and the Travel Industry Association ofAmerica. Jonathan B. Tourtellot, editor of National Geographic, and wife Sally Bensusen coined the term a few years earlier due to the need for a concept more encompassing than simply sustainable tourism or ecotourism. -

SOUVENIR MARKETING in TOURISM RETAILING SHOPPER and RETAILER PERCEPTIONS by KRISTEN K

SOUVENIR MARKETING IN TOURISM RETAILING SHOPPER AND RETAILER PERCEPTIONS by KRISTEN K. SWANSON, B.S., M.S. A DISSERTATION IN CLOTHING, TEXTILES, AND MERCHANDISING Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Accepted August, 1994 1 o t.i.H" ^b^/ •b C'J ® 1994 Kristen Kathleen Swanson ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The researcher would like to thank Dr. Patricia Horridge, advisor and friend, for her guidance and support at Texas Tech University. Dr. Horridge continually gives of herself to encourage and inspire her students. Additionally, this researcher would like to thank Dr. Claud Davidson, Dr. linger Eberspacher, Dr. Lynn Huffman, and Dr. JoAnn Shroyer for allowing this exploratory research to take place, and keep the study grounded. Each committee member took time to listen, evaluate and strengthen this study. Thank you to Tom Combrink, Arizona Hospitality Research and Resource Center, Northern Arizona University, for assisting with the statistical analysis. Further, this researcher would like to thank all of the graduate students who came before her, for it is by their accomplishments and mistakes that the present study was enhanced. The researcher would like to thank her husband James Power, her parents Richard and Bonnie Swanson, and Bill and Ruby Power, and special friends Chris and Judy Everett for their constant support in accomplishing this study and the degree which comes with the work. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii ABSTRACT vii LIST OF TABLES ix CHAPTER L INTRODUCTION 1 Theoretical Framework 2 Statement of Problem 3 Purposes of the Study 6 Research Objectives and Questions 7 Research Objectives 7 Research Questions 8 Limitations 9 Definition of Terms 9 II. -

THE Opportunlty of a Generation: the Litimate Score on A, Oigita Go D Mine

THE OPPORTUnlTY OF A GEnERATIOn: The Litimate Score on a, Oigita Go d Mine ...,:: ------- . ....... ' ,,,.,, .. ,,,,,. , ..... TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.............................................................................................3 Demographic Shifts and Opportunities………..........................................5 The Millennial Hotspot............................................................................6 The Future of the Video Game Industry.................................................8 The Evolution of Sports……………….........................................................11 eSports Celebrities - 8-Figure Digital Athletes......................................14 An Enormous Money-Making Opportunity...........................................16 Microtransactions..................................................................................18 Market Sector Size.................................................................................21 Video Games - A Well-Kept Secret........................................................23 Featured Investment Opportunity........................................................24 Management and Ownership......................................................24 Portfolio of Assets.......................................................................27 Target Market and Comparables................................................32 Chinese e-Gaming Comparables.................................................36 Game Analysis: Revenue and Cashflow Targets.........................40 -

Massachusetts Schools of Cosmetology, Barbering and Electrology Private & Vocational Schools

MASSACHUSETTS SCHOOLS OF COSMETOLOGY, BARBERING AND ELECTROLOGY PRIVATE & VOCATIONAL SCHOOLS COSMETOLOGY Blackstone Valley Regional Voc Tech School-Cosmetology Dept Aesthetic Institute of Boston Cosmetology Program 47 Spring Street 65 Pleasant Street West Roxbury, MA 02132 Upton, MA 01568 617-327-4550 508-529-7758 Alexander Academy Inc. Blessing Channels Nail Academy Cosmetology and Barbering Program Manicuring Program 112 River Street 76 Winn St #1C Fitchburg, MA 01420 Woburn, MA 01801 978-345-0011 781-729-8868 Aliano School of Cosmetology, Inc. Blue Hills Regional Tech Sch. Cosmetology Program Cosmetology/Aesthetic Program 541 West Street 800 Randolph Street PO Box 4740 Canton, MA 02021 Brockton, MA 02303 781-828-5800 508-583-5433 BMC Durfee High School Ali May Aesthetic Academy Cosmetology Program Aesthetic Program 360 Elsbree Street 1459 Hancock St Fall River, MA 02720 Quincy, MA 02169 508-675-8100 617-438-2753 Bojack Academy of Beauty Culture Ali May Aesthetic Academy Cosmetology/Aesthetic Programs Manicuring Program 47 Spring Street 1459 Hancock St W. Roxbury, MA 02132 Quincy, MA 02169 617-323-0844 617-438-2753 Bristol-Plymouth Reg Tech Sch. Assabet Valley Regional HS Cosmetology Program Cosmetology/Aesthetic Program 940 County Street, Route 140 215 Fitchburg Street Taunton, MA 02780 Marlboro, MA 01752 508-823-5151 508-485-9430 x 1447 C.H. McCann Tech. High School Bay Path Voc. Tech HS Cosmetology Program Cosmetology Program Hodges Cross Road 57 Old Mugget Hill Road North Adams, MA 01247 Charlton, MA 01507 413-663-8424 508-248-5971 1 of 8 (rev. 4/19/2016) MASSACHUSETTS SCHOOLS OF COSMETOLOGY, BARBERING AND ELECTROLOGY PRIVATE & VOCATIONAL SCHOOLS Cali for Nails Academy Digrigoli School of Cosmetology Manicuring Program Cosmetology Program 204 Adams Street 1578 Riverdale Street Dorchester, MA 02122 W. -

The General Store Era: Memoirs of Arthur and Harold Mittelstaedt

Copyright © 1978 by the South Dakota State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. The General Store Era: Memoirs of Arthur and Harold Mittelstaedt ROBERT A. MITTELSTAEDT Editor From colonial times to the early twentieth century, the general store was an important part of almost every rural community and small town in America. Although there is a tendency to em- phasize its social role, either as a gathering of Yankee story tellers around a potbellied stove with a cat dozing in an open cracker barrel or as the basis for a "leading family's" power in some Faulkneresque Deep South village, the general store sur- vived in rural America because it performed two important economic functions. First, it made available a diversified inven- tory of nonlocally produced goods and, second, it served as a marketing agency for locally produced commodities and crafts.' While bearing some resemblance to their Yankee and Southern predecessors, the general stores of the small towns in South Dakota reflected a different set of conditions. Their origins were as part of a business district in a town, probably founded by the railroad as the tracks were laid, which had been consciously in- tended as a trading center for the simultaneously developing cash farming operations that would surround it.^ Since these new towns also included single-line competitors, such as drug stores, apparel stores, and hardware stores, in addition to hotels, 1. Gerald Carson, The Old Country Store (New York: Oxford University Press, 1954); Lewis E. Atherton, The Southern Country Store, 1800-1860 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1949). -

The Healthy Convenience Store Project

THE HEALTHY CONVENIENCE STORE PROJECT PROVIDED BY: Southern Illinois Healthy Convenience Store Project: A Toolkit for LHDs, Organizers and Store Owners This toolkit was developed for Southern Illinois local health departments and community organizers to assist in encouraging local convenience stores to adopt healthier food choices. For more information, please contact: Questions specific to the toolkit: Jackson County Health Department Miriam Link-Mullison [email protected] 618-684-3143 x100 Southern Illinois What is in the Toolkit? Healthy Convenience Store Project Introduction Organizer Toolkit What is a Healthy Convenience Store Project? Project Process Store Selection Process Marketing Tools Technical Assistance Healthy Convenience Store Toolkit What is the Healthy Convenience Store Project? Project Expectations Making the Store Project Plan Marketing Healthy Foods Stocking, Displaying, & Purchasing Fresh Fruit and Vegetables What are Healthy Foods? WIC & Food Stamps (SNAP) Resources Appendix Southern Illinois Introduction Healthy Convenience Store Project The Project This project focuses on making healthy food more accessible to rural residents, particularly those who must travel a long distance to grocery shopping. Residents in these areas must rely on convenience stores for grocery shopping in between periodic supermarket shopping trips. As a result, making healthy food available to these residents depends on improving what is stocked on the shelves of convenience stores. This project attempts to address this problem by encouraging retailers to incorporate more healthy food options into their stores through a healthy convenience store program. Who We Are: The Healthy Southern Illinois Delta Network (HSIDN) is a grassroots effort established to build consensus on the health needs of residents in southernmost Illinois. -

UVRA GPS Field/Gym Locations & Directions

UVRA GPS Field/Gym Locations & Directions CCBA Witherell Center – 1 Campbell Street, Lebanon NH 03766 From the North: I-89 south to Exit 18 (DHMC/Lebanon High School). Bear right off the exit and continue on Route 120 to stop sign. Turn left onto Hanover St. Follow Hanover St. for approximately 1/2 mile and take a left into the parking lot next to Village Pizza/Peking Tokyo/Lebanon Floral mini-mall. Stay to the left and go down a slight hill bearing to the right at the bottom of the hill. Continue around the municipal parking lot onto Taylor St. The Witherell Center will be on you left. From the South: I-89 to Exit 17 (Enfield/Lebanon).Take a left off the exit and follow Route 4 into downtown Lebanon. Approx. 3 miles. At the green take your first right onto Campbell St. Turn right at the end of Campbell St. onto Parkhurst St. Take your first left onto Spencer St., go approx. 100 yards and drive straight into the Witherell Center's parking lot. CLAREMONT From I-91 south or north: to Exit #8, route 103 to the center of Claremont. At the rotary/parking in center of town, take the third right (city hall on the left). You are now on Broad Street. Broad Street Park (gazebo in center) is on your left. Now follow the directions to the place you are playing at: Monadnock Park – Broad Street, Claremont NH 03743 Go ¼ mile down Broad Street. Stevens High School is on the right. After passing Stevens High take your first left which is the access road leading down into Monadnock Park. -

DECISION the Log Cabin General Store

Application by Tracey Skeet for a special licence for the premises The Log Cabin General Store, at 59 Burgess Street, Bicheno, 7215. Decision: Licence refused Date: 08 December 2020 The application The applicant seeks authority to sell Tasmanian liquor products under a special licence for consumption off the premises. The applicant describes the locality of the premises as a popular tourist destination for short-term accommodation, including camping. The current use of the premises is described as a general and hardware convenience store that provides a wide array of products, with a focus on providing items from the east coast and Tasmania generally. Opening hours are 9am to 3pm on weekdays and 10am to 2pm on weekends and public holidays. Off-street parking is available. The applicant indicates that the use of the premises will be modified in order to provide a wider range of Tasmanian products, including Tasmanian wine, beer and spirits to further enhance the customer experience. Liquor products would be incorporated without the need for substantial modifications. The applicant indicates that in the immediate local area liquor suppliers are limited, with only The Farm Shed providing a similar service to her proposal. The applicant states that the premises is more of a tourist and souvenir shop. Milk has only been stocked due to the coronavirus pandemic to meet local demand. Other than that she does not sell convenience store items. Online sites for the business confirm that stocks include homeware, souvenirs, hardware, art and garden supplies, camping and fishing products, gourmet goods and a few grocery items. -

Transportation, Traffic and Parking

Chapter from DPIR/DEIR dated 2-18-20 Bunker Hill Housing Redevelopment – DEIR-NPC/DPIR 5 Transportation This chapter provides an assessment of the Project’s transportation characteristics. The chapter includes evaluations of existing conditions and projected future conditions without and with the proposed Project (i.e., No-Build and Build conditions, respectively). Transportation improvements and mitigation measures are identified to address existing transportation problems in the area in addition to minimizing potential impacts of the Project. In addition to physical multi-modal transportation infrastructure improvements, the mitigation package includes a robust Transportation Demand Management (TDM) plan designed to reduce single- occupant vehicle (SOV) travel and encourage use of alternative transportation modes. The Proponent will commit to these improvements through the execution of a Transportation Access Plan Agreement (TAPA) with the City of Boston. Key Findings The key findings of the transportation analysis include the following: The Proponent seeks to obtain a Phase 1 waiver in order to start construction on the first phase of construction while the Full Build Master Plan continues through the MEPA regulatory review process: This transportation analysis has been completed for both Phase 1 and the Full Build Master Plan (inclusive of Phase 1). The Phase 1 Project is expected to generate approximately 702 net new daily vehicle trips, with approximately 58 and 82 net new vehicle trips occurring in the morning and evening peak hours, respectively; The Full Build Master Plan is expected to generate approximately 5,006 net new daily vehicle trips, with approximately 382 and 533 net new vehicle trips occurring in the morning and evening peak hours, respectively.