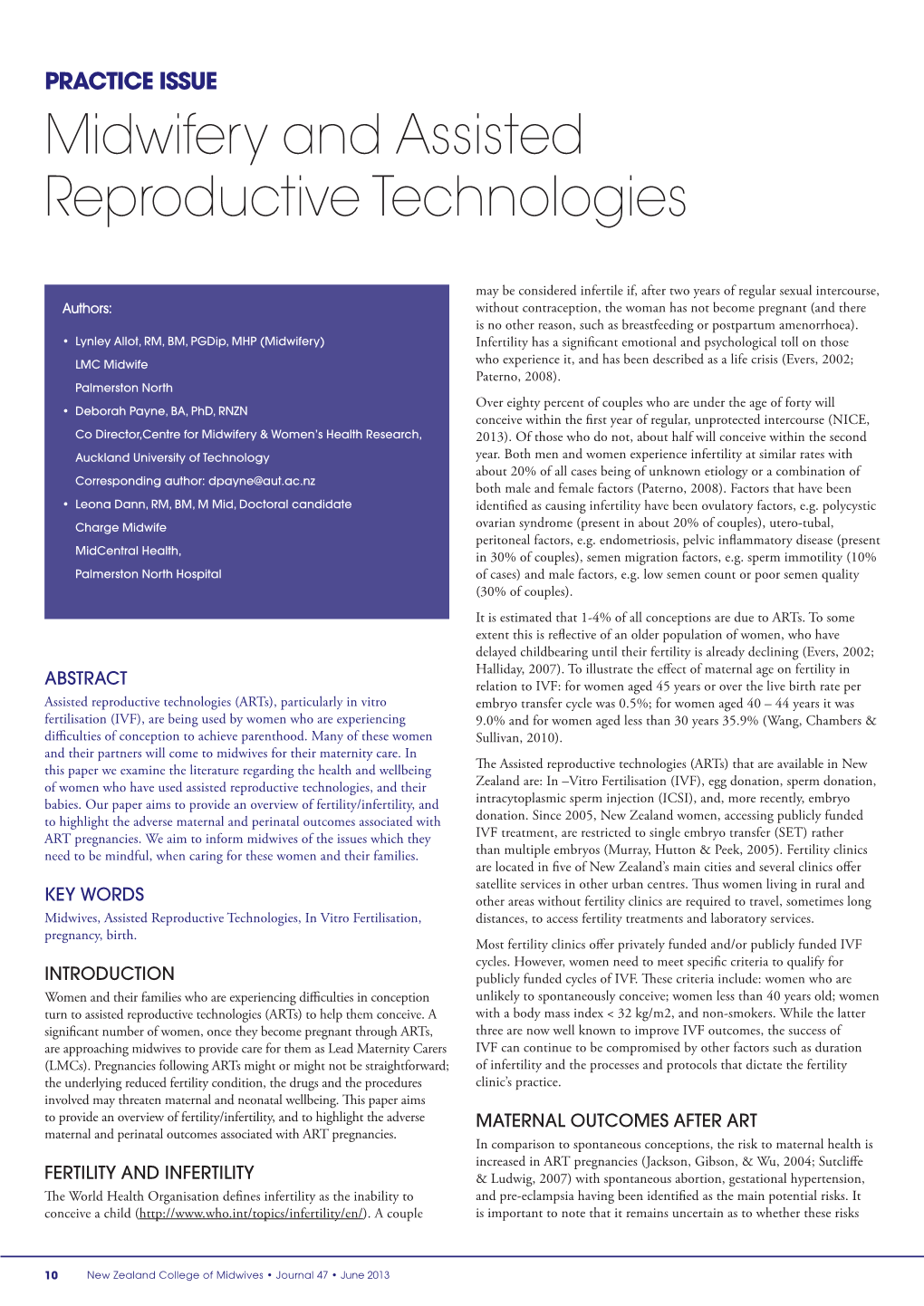

Midwifery and Assisted Reproductive Technologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of a Midwife in Assisted Reproductive Units

Clinical Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Medicine Research Article ISSN: 2059-4828 The role of a midwife in assisted reproductive units O Tsonis1, F Gkrozou2*, V Siafaka3 and M Paschopoulos1 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Hospital of Ioannina, Greece 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, university Hospitals of Birmingham, UK 3Department of Speech and Language Therapy, School of Health Sciences, University of Ioannina, Greece Abstract Problem: The role of midwifery in Assisted Reproductive Units remains unclear. Background: Midwives are valuable health workers in every field or phase of women’s health. Their true value has been consistently demonstrated and regards mainly their function in labour. Infertility is a quite new territory in which a great deal of innovating approaches has been made through the years. Aim: The aim of this study is to present the role of midwifery in Assisted Reproductive Units based on scientific data Methods: For this review 3 (three) major search engines were included MEDLINE, PubMed and EMBASE focusing on the role of midwives in the assisted reproductive units. Findings: It seems that midwives have three distinct roles, when it comes to emotional management of the infertile couple, being the representative of the infertile couple and also, performing assisted reproductive techniques in some cases. Their psychomedical support is profound and, in this review, we try to research their potential role in the assisted reproductive units. Discussion: In the literature, only few scientific articles have been conducted in search of the role of Midwifery in Infertility. Their importance is once again undeniable and further research needs to be conducted in order to increase their adequate participation into this medical field. -

Experiences of Transition to Motherhood Among Pregnant Women Following Assisted Reproductive Technology: a Systematic Review Protocol of Qualitative Evidence

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW PROTOCOL Experiences of transition to motherhood among pregnant women following assisted reproductive technology: a systematic review protocol of qualitative evidence 1,2 1,2 1,2 1,2 1,2 Kunie Maehara Hiroko Iwata Mai Kosaka Kayoko Kimura Emi Mori 1Graduate School of Nursing, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan, 2The Chiba University Centre for Evidence Based Practice: a Joanna Briggs Institute Affiliated Group ABSTRACT Objective: This systematic review aims to identify and synthesize available qualitative evidence related to the experiences of transition to motherhood during pregnancy in women who conceived through assisted reproductive technology (ART). Introduction: Women who conceived through ART experience pregnancy-specific anxiety and paradoxical feelings, and face unique challenges in their identity transition to motherhood. It is important for healthcare professionals working with these women to understand the context and complexity of this special path to parenthood, including the emotional adaptation to pregnancy following ART. A qualitative systematic review can provide the best available evidence to inform development of nursing interventions to meet the needs of pregnant women after ART. Inclusion criteria: This review will consider any qualitative research data from empirical studies published from 1992–2019 in English or Japanese that described experiences of transition to motherhood during pregnancy in women who conceived with ART. Methods: This review will follow the JBI approach for qualitative systematic reviews. Databases that will be searched for published and unpublished studies include MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, ProQuest Health & Medical Collection, Google Scholar and Open Access Theses and Dissertations (in English), and Ichushi-Web, CiNii and the Institutional Repositories Database (in Japanese). -

The Factors Affecting Amniocentesis Decision by Pregnant Women in the Risk Group and the Influence of Consultant

A L J O A T U N R I N R A E L P Original Article P L E R A Perinatal Journal 2019;27(1):6–13 I N N R A U T A L J O ©2019 Perinatal Medicine Foundation The factors affecting amniocentesis decision by pregnant women in the risk group and the influence of consultant Kanay Yararbafl1 İD , Ayflegül Kuflkucu2 İD 1Department of Medical Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, Ac›badem Mehmet Ali Ayd›nlar University, Istanbul, Turkey 2Department of Medical Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, Yeditepe University, Istanbul, Turkey Abstract Özet: Risk grubundaki gebelerin amniyosentez karar› almas›ndaki faktörler ve genetik dan›flman›n etkisi Objective: The most frequent goal for prenatal diagnosis is to Amaç: Do¤um öncesi tan›da günümüzde en s›k amaçlanan hedef detect pregnancies with Down syndrome. Since karyotyping, which Down sendromlu gebelikleri tespit etmektir. Tan›da alt›n standart is the golden standard for the diagnosis, has not been replaced with yöntem olan karyotiplemenin yerini henüz non-invaziv bir yön- a non-invasive method, pregnant women in the risk group should tem dolduramad›¤›ndan, CVS, amniyosentez gibi bir yöntem için choose the method such as CVS and amniocentesis. Therefore, risk alt›ndaki gebelerin seçimi gereklidir. Bu amaçla giriflimsel ol- screening tests are performed by non-invasive method, and preg- mayan yöntemlerle tarama testleri yap›lmakta, riskli gebelere ge- nant women under risk are provided genetic consultation and the netik dan›flma verilerek invaziv giriflim karar› aileye b›rak›lmakta- family is expected to make a decision for invasive procedure. -

Report Title: Celebrating Birth – Aboriginal Midwifery in Canada

Report title: Celebrating Birth – Aboriginal Midwifery in Canada © Copyright 2008 National Aboriginal Health Organization ISBN: 978-1-926543-11-6 Date Published: December 2008 OAAPH [now known as the National Aboriginal Health Organization (NAHO)] receives funding from Health Canada to assist it to undertake knowledge-based activities including education, research and dissemination of information to promote health issues affecting Aboriginal persons. However, the contents and conclusions of this report are solely that of the authors and not attributable in whole or in part to Health Canada. The National Aboriginal Health Organization, an Aboriginal-designed and -controlled body, will influence and advance the health and well-being of Aboriginal Peoples by carrying out knowledge-based strategies. This report should be cited as: National Aboriginal Health Organization. 2008. Celebrating Birth – Aboriginal Midwifery in Canada. Ottawa: National Aboriginal Health Organization. For queries or copyright requests, please contact: National Aboriginal Health Organization 220 Laurier Avenue West, Suite 1200 Ottawa, ON K1P 5Z9 Tel: (613) 237-9462 Toll-free: 1-877-602-4445 Fax: (613) 237-1810 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.naho.ca Under the Canadian Constitution Act, 1982, the term Aboriginal Peoples refers to First Nations, Inuit and Métis people living in Canada. However, common use of the term is not always inclusive of all three distinct people and much of the available research only focuses on particular segments of the Aboriginal population. NAHO makes every effort to ensure the term is used appropriately. Acknowledgements The original Midwifery and Aboriginal Midwifery in Canada paper was published by the National Aboriginal Health Organization (NAHO) in May 2004. -

Statement on Unassisted Birth Attended by a Doula

Statement On Unassisted Birth Attended by a Doula _______________________________________________________ Definition Unassisted childbirth – the process of intentionally giving birth without the assistance of a medical or professional birth attendant – is a decision made by a very small percentage of parents. DONA International certified and member doulas provide physical, informational and emotional support. Any type of medical or clinical assistance is outside the scope of practice agreed upon by DONA International certified and member doulas. DONA International opines herein on the considerations a doula must make when accepting clients planning an unassisted birth. Introduction Unassisted childbirth (UC) refers to the process of intentionally giving birth without the assistance of a medical or professional birth attendant. UC is also sometimes referred to as free birth, DIY (do-it-yourself) birth, unhindered birth and couples birth. In response to the recent growth in interest over UC, several national medical societies, including the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canadai, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologistsii, and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologistsiii, have issued strongly worded public statements warning against the practice. Professional midwives' associations, including the Royal College of Midwivesiv and the American College of Nurse-Midwivesv also caution against UC. Those who promote UCvi claim the practice offers mothers-to-be a natural way of welcoming their child into the world, free from drugs, machinery and medical intervention. They also note that UC allows a woman to listen to her body's signals rather than coaching from an outsider. The women who are choosing UC may do so because they do not feel supported and respected in the obstetrical care facilities available in their areas, or they are unable to afford or obtain home midwifery or physician support, which is more in line with their philosophies. -

Midwifery: a Career for Men in Nursing

Midwifery: A career for men in nursing It may not be a common path men take, but how many male midwives are there? By Deanna Pilkenton, RN, CNM, MSN, and Mavis N. Schorn, RN, CNM, PHD(C) Every year, faculty at Vanderbilt University School of there are so few men in this profession. In fact, these Nursing reviews applications to the school’s nurse- conversations often lead to the unanimous sentiment midwifery program. The applicants’ diversity is always that men shouldn’t be in this specialty at all. Scanning of interest. A wide spectrum of age is common. A pleas- the web and reviewing blog discussions on this topic ant surprise has been the gradual improvement in the confirms that it’s a controversial idea, even among Eethnic and racial diversity of applicants. Nevertheless, midwives themselves. male applicants are still rare. It’s common knowledge that the profession of nurs- Many people wonder if there’s such thing as a male ing is female dominated, and the challenges and com- midwife. There are male midwives; there just aren’t plexities of this have been explored at length. many of them. When the subject of men in midwifery is Midwifery, however, may be one of the most exclusive- discussed, it usually conjures up perplexed looks. The ly and disproportionately female specialties in the field very idea of men in midwifery can create quite a stir, of nursing and it’s time to acknowledge the presence of and most laypeople don’t perceive it as strange that male midwives, the challenges they face, and the posi- www.meninnursingjournal.com February 2008 l Men in Nursing 29 tive attributes they bring to the pro- 1697, is credited with innovations fession. -

Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring This Document Should Be Read in Conjunction with the Disclaimer

King Edward Memorial Hospital Obstetrics & Gynaecology CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE Fetal heart rate monitoring This document should be read in conjunction with the Disclaimer This guideline must be read in conjunction with the Department of Health WA Mandatory Policy: MP 0076/18: Cardiotocography Monitoring Policy. The following Clinical Guideline complies with the Cardiotocography Monitoring Standard. Contents General requirements ........................................................................... 2 Indications for performing a cardiotocograph (CTG) ............................................... 2 Review, interpretation and signing of traces ........................................................... 4 Education and Fetal Surveillance Education Program (FSEP) practitioner levels ... 4 Storage ................................................................................................................... 4 Antenatal fetal heart rate (FHR) monitoring ........................................ 5 Key points ............................................................................................................... 5 Procedure ............................................................................................................... 5 Documentation ........................................................................................................ 5 Monitoring and additional information ..................................................................... 6 Escalation of care- antenatal .................................................................................. -

Consensus Statement: Alcohol and Pregnancy

Consensus Statement: Alcohol and Pregnancy The New Zealand College of Midwives recognises that there is no known safe level of alcohol consumption at any stage of pregnancy. Therefore parents planning a pregnancy and women who are pregnant should be advised not to drink alcohol. Rationale: • Women’s drinking does not happen in isolation. It is shaped by their social, environmental and cultural context. In New Zealand, this context includes the normalisation of alcohol consumption within our culture, particularly at social events. 1,4 • Alcohol passes freely through the placenta and reaches concentrations in the fetus that are as high as those in the mother. 1,2,3 • Alcohol is a teratogen – a substance that may affect the development of a fetus. 1,2, 3 • Drinking alcohol during pregnancy can cause the baby to be born with a range of alcohol-related birth impairments known as Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) 1,2,4. o FASD is an umbrella term for a range of lifelong physical, cognitive and behavioral impairments of varying severity including Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS). • Drinking alcohol during pregnancy also increases the risks of miscarriage, prematurity and stillbirth. • Risk of alcohol harm to the fetus is proportional to the amount of alcohol consumed. Damage to the fetus is more likely to occur with high blood alcohol levels. 1,3,4 • There is no known safe level of alcohol consumption during pregnancy 1,3,4 • There is no known safe time to drink alcohol during pregnancy. 1,2,4 Practice Guidance: Midwives have a role in advising women against alcohol consumption during pregnancy, explaining the potential consequences and supporting women to address their alcohol use during pregnancy. -

Information for Patients

Information for patients Planning for your Home Birth This section is for the patient to make notes if they so wish: Name: _______________________________ Who to contact and how: _______________________________ Notes: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Diana, Princess of Scunthorpe General Goole & District Wales Hospital Hospital Hospital Scartho Road Cliff Gardens Woodland Avenue Grimsby Scunthorpe Goole DN33 2BA DN15 7BH DN14 6RX 03033 306999 03033 306999 03033 306999 www.nlg.nhs.uk www.nlg.nhs.uk www.nlg.nhs.uk For more information about our Trust and the services we provide please visit our website: www.nlg.nhs.uk Information for patients Introduction This information leaflet has been produced for women who are considering a home birth. It includes details on the benefits and risks of a home birth, what to expect, and what you will need in preparation for a home birth. If you decide to plan a home birth, your community midwife should support you in your choice and help you prepare for your birth (NHS, 2017). During a home birth, a community midwife will come to your home to look after you during labour and for a short while after the birth of your baby. There are community midwives on call 24 hours, so the midwife will come to your home to assess you when you think you are in labour (NHS, 2017). What are the advantages of having a home birth? • Women report feeling much more satisfied with their birth experience at home when compared to a -

Amniocentesis and CVS UHL Obstetric Guideline

Amniocentesis and Chorionic Villus Sampling Maternity 1. Introduction and Scope This guideline is intended for the use of obstetric and midwifery staff involved in the care of pregnant women undergoing amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling (CVS). It is estimated that around 5% of the pregnant population (approximately 30,000 women per annum in the UK) are offered a choice of invasive prenatal diagnostic tests. The type of test offered is dependent on several factors including gestational age, indication and placental position. Amniocentesis is the most common invasive antenatal diagnostic procedure undertaken in the United Kingdom (UK). Most amniocenteses are performed to obtain amniotic fluid for karyotyping. It is a procedure to remove amniotic fluid from the uterus. CVS involves aspiration or biopsy of placental villi and can be done via trans abdominal or trans cervical methods. In UHL this is done by a trans abdominal approach. 2. Recommendations 1. Women undergoing amniocentesis or CVS should be fully counselled prior to the procedure of the risks involved and informed consent documented. 2. Amniocentesis and CVS should be performed at the appropriate gestation. 3. A safe technique should be used to perform amniocentesis and CVS. 4. Operators performing amniocentesis and CVS should be trained to the local competencies expected, those expected by the Royal College of Obstetricians (RCOG) or an international equivalent. 5. Clinical considerations for performing amniocentesis or CVS for multiple pregnancy / in the third trimester / IUD / BBI. 1. Women undergoing amniocentesis or CVS should be fully counselled prior to the procedure and informed consent documented. Women should be advised of the risks of undergoing amniocentesis or CVS. -

PRECONCEPTION and HEALTH Research & Strategies

PRECONCEPTION and HEALTH RESEARCH & STRATEGIES PRECONCEPTION and HEALTH research & strategies Best Start: Ontario’s Maternal, Newborn and Early Child Development Best Start: Ontario’s Maternal, Newborn Resource Centre and Early Child Development Resource Centre 180 Dundas St., West, Suite 1900 TORONTO, ON M5G 1Z8 www.beststart.org 2001 $&.12:/('*(0(176 The Best Start: Ontario’s Maternal, Newborn and Early Child Development Resource Centre would like to thank the many people who helped develop this resource. Their input was invaluable in ensuring accurate and up-to-date content and a practical format. Susan Taylor-Clapp conducted the literature review, under the direction of the working group. “Preconception and Health: Research and Strategies” was prepared by the Perinatal Partnership Program of Eastern and Southeastern Ontario in collaboration with the following individuals and organizations: (OL]DEHWK%HUU\2QWDULR0LQLVWU\RI+HDOWKDQG/RQJWHUP&DUH -DQHWWH%RZLH+DOWRQ+HDOWK8QLW :HQG\%XUJR\QH%HVW6WDUW2QWDULR·V0DWHUQDO1HZERUQDQG(DUO\&KLOG'HYHORSPHQW5HVRXUFH&HQWUH .DWK\&URZH&LW\RI2WWDZD+HDOWK'HSDUWPHQW .DUHQ)XQJ.HH)XQJ2WWDZD*HQHUDO+RVSLWDO &ODXGHWWH1DGRQ&LW\RI2WWDZD+HDOWK'HSDUWPHQW 3DWULFLD1LGD\3HULQDWDO3DUWQHUVKLS3URJUDPRI(DVWHUQ 6RXWKHDVWHUQ2QWDULR $QQ6SUDJXH3HULQDWDO3DUWQHUVKLS3URJUDPRI(DVWHUQDQG6RXWKHDVWHUQ2QWDULR 6XVDQ7D\ORU&ODSS3HULQDWDO3DUWQHUVKLS3URJUDPRI(DVWHUQDQG6RXWKHDVWHUQ2QWDULR 5RELQ:DONHU&KLOGUHQ·V+RVSLWDORI(DVWHUQ2QWDULR %DUEDUD:LOOHW%HVW6WDUW2QWDULR·V0DWHUQDO1HZERUQDQG(DUO\&KLOG'HYHORSPHQW5HVRXUFH&HQWUH 0HUU\.0RRV'LYLVLRQRI0DWHUQDO)HWDO0HGLFLQH8QLYHUVLW\RI1RUWK&DUROLQD -

Alcohol Guidelines for Pregnant Women Barriers and Enablers for Midwives to Deliver Advice

August 2019 Alcohol guidelines for pregnant women Barriers and enablers for midwives to deliver advice Lisa Schölin, Julie Watson, Judith Dyson and Lesley Smith ALCOHOL GUIDELINES FOR PREGNANT WOMEN: BARRIERS AND ENABLERS FOR MIDWIVES TO DELIVER ADVICE Alcohol guidelines for pregnant womeN Barriers and enablers for midwives to deliver advice Authors Lisa Schölin, Julie Watson, Judith Dyson and Lesley Smith. Acknowledgements The authors would like to dedicate this report to Pip Williams, member of the stakeholder group, who sadly passed away before this study was completed. Pip was a strong advocate for FASD birthmothers and those living with FASD themselves and worked incredibly hard to raise awareness of the issues women with lived experience of addiction face. She was an inspiring, strong, dedicated, and compassionate woman and her legacy will continue to inspire people in the field. We are deeply grateful for the input she had in this study and we will miss her. We would also like to acknowledge all midwives who took part in this study, who we know are working under increasingly demanding pressures and still took the time to share their knowledge and experiences of this topic. Finally, we also want to acknowledge the stakeholder group who helped shape this study, supported recruitment, and will help share the results. The authors would also like to thank Professor Linda Bauld, University of Edinburgh, and Clare Livingstone, Royal College of Midwives, for reviewing the report. Image credit: MachineHeadz / iStock. Funding The report was