State Scope of Practice Laws, Nurse-Midwifery Workforce, and Childbirth Procedures and Outcomes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of a Midwife in Assisted Reproductive Units

Clinical Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Medicine Research Article ISSN: 2059-4828 The role of a midwife in assisted reproductive units O Tsonis1, F Gkrozou2*, V Siafaka3 and M Paschopoulos1 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Hospital of Ioannina, Greece 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, university Hospitals of Birmingham, UK 3Department of Speech and Language Therapy, School of Health Sciences, University of Ioannina, Greece Abstract Problem: The role of midwifery in Assisted Reproductive Units remains unclear. Background: Midwives are valuable health workers in every field or phase of women’s health. Their true value has been consistently demonstrated and regards mainly their function in labour. Infertility is a quite new territory in which a great deal of innovating approaches has been made through the years. Aim: The aim of this study is to present the role of midwifery in Assisted Reproductive Units based on scientific data Methods: For this review 3 (three) major search engines were included MEDLINE, PubMed and EMBASE focusing on the role of midwives in the assisted reproductive units. Findings: It seems that midwives have three distinct roles, when it comes to emotional management of the infertile couple, being the representative of the infertile couple and also, performing assisted reproductive techniques in some cases. Their psychomedical support is profound and, in this review, we try to research their potential role in the assisted reproductive units. Discussion: In the literature, only few scientific articles have been conducted in search of the role of Midwifery in Infertility. Their importance is once again undeniable and further research needs to be conducted in order to increase their adequate participation into this medical field. -

Childbirth Education Booklet

Childbirth Education Contents Normal Discomforts of Pregnancy 2 Call Your Doctor 4 Late Pregnancy 5 Labor: Stage 1 6 Labor: Stages 2 & 3 8 Breastfeeding in the Hospital 9 Breathing Techniques 10 Birth Plans 10 Labor Positions 11 How Your Partner and Doula Can Help 13 Packing for the Hospital 15 Normal Discomforts of Pregnancy Fatigue Backache • Listen to your body, take naps, get extra rest • Maintain correct posture • Do pelvic tilt exercises while standing and on hands Stuffy Nose and knees • Warm compresses to nose • While on all fours, crawl forwards and backwards, • Cool mist humidifier in your home or rock, and do pelvic tilts bedroom at night • When picking up something lift with your legs to protect your back Shortness of Breath • Don’t stay that way, slow down and catch your breath • For prolonged standing, elevate 1 foot on a step stool • Sleep propped up with pillows or in recliner • Receive back massages • Maintain correct posture Dribble Urine • Moderate intensity exercising (walking, stationary • Do Kegel exercises – at least 50 a day bike, swim, flexibility moves) (do 10 every time you wash your hands) • How can you tell if you are dribbling urine or your Heartburn/Nausea water broke? Call your OB or midwife, and remember • Don’t eat 3 big meals a day, eat 5-6 smaller meals this acronym: • Drink 8 cups of water a day COAT. C=color, O=odor, A=amount, T=time. • Have dry crackers/cereal to nibble on–keep in purse and at bedside • Don’t let stomach become empty • Eat well balanced diet–vitamin B may help to decrease • Avoid -

The Effects of Alcohol in Newborns Efeitos Do Álcool No Recém-Nascido

REVIEW The effects of alcohol in newborns Efeitos do álcool no recém-nascido Maria dos Anjos Mesquita* ABSTRACT alcoólicas leva a prejuízos individuais, para a sua família e para The purpose of this article was to present a review of the effects toda a sociedade. Apesar disso, a dificuldade do seu diagnóstico e of alcohol consumption by pregnant mothers on their newborn. a inexperiência dos profissionais de saúde faz com que o espectro Definitions, prevalence, pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnostic dessas lesões seja pouco lembrado e até desconhecido. As lesões criteria, follow-up, treatment and prevention were discussed. A causadas pela ação do álcool no concepto são totalmente prevenidas search was performed in Medline, LILACS, and SciELO databases se a gestante não consumir bebidas alcoólicas durante a gestação. using the following terms: “fetus”, “newborn”, “pregnant woman”, Assim, é fundamental a detecção das mulheres consumidoras “alcohol”, “alcoholism”, “fetal alcohol syndrome”, and “alcohol- de álcool durante a gravidez e o desenvolvimento de programas related disorders”. Portuguese and English articles published from específicos de alerta sobre as consequências do álcool durante a 2000 to 2009 were reviewed. The effects of alcohol consumed by gestação e amamentação. pregnant women on newborns are extremely serious and occur frequently; it is a major issue in Public Health worldwide. Fetal alcohol Descritores: Bebidas alcoólicas/efeitos adversos; Feto; Recém-nascido; spectrum disorders cause harm to individuals, their families, and the Síndrome alcoólica fetal; Transtornos relacionados ao uso de álcool entire society. Nevertheless, diagnostic difficulties and inexperience of healthcare professionals result in such damage, being remembered rarely or even remaining uncovered. -

Experiences of Transition to Motherhood Among Pregnant Women Following Assisted Reproductive Technology: a Systematic Review Protocol of Qualitative Evidence

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW PROTOCOL Experiences of transition to motherhood among pregnant women following assisted reproductive technology: a systematic review protocol of qualitative evidence 1,2 1,2 1,2 1,2 1,2 Kunie Maehara Hiroko Iwata Mai Kosaka Kayoko Kimura Emi Mori 1Graduate School of Nursing, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan, 2The Chiba University Centre for Evidence Based Practice: a Joanna Briggs Institute Affiliated Group ABSTRACT Objective: This systematic review aims to identify and synthesize available qualitative evidence related to the experiences of transition to motherhood during pregnancy in women who conceived through assisted reproductive technology (ART). Introduction: Women who conceived through ART experience pregnancy-specific anxiety and paradoxical feelings, and face unique challenges in their identity transition to motherhood. It is important for healthcare professionals working with these women to understand the context and complexity of this special path to parenthood, including the emotional adaptation to pregnancy following ART. A qualitative systematic review can provide the best available evidence to inform development of nursing interventions to meet the needs of pregnant women after ART. Inclusion criteria: This review will consider any qualitative research data from empirical studies published from 1992–2019 in English or Japanese that described experiences of transition to motherhood during pregnancy in women who conceived with ART. Methods: This review will follow the JBI approach for qualitative systematic reviews. Databases that will be searched for published and unpublished studies include MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, ProQuest Health & Medical Collection, Google Scholar and Open Access Theses and Dissertations (in English), and Ichushi-Web, CiNii and the Institutional Repositories Database (in Japanese). -

Care During Pregnancy and Delivery ACCESSIBLE, QUALITY HEALTH CARE DURING PREGNANCY and DELIVERY

Care during Pregnancy and Delivery ACCESSIBLE, QUALITY HEALTH CARE DURING PREGNANCY AND DELIVERY Why It’s Important Having a healthy pregnancy and access to quality birth facilities are the best ways to promote a healthy birth and have a thriving newborn. Getting early and regular prenatal care is vital. Prenatal care is the health care that women receive during their entire pregnancy. Prenatal care is more than doctor’s visits and ultrasounds; it is an opportunity to improve the overall well-being and health of the mom which directly affects the health of her baby. Prenatal visits give parents a chance to ask questions, discuss concerns, treat complications in a timely manner, and ensure that mom and baby are safe during pregnancy and delivery. Receiving quality prenatal care can have positive effects long after birth for both the mother and baby. When it is time for the mother to give birth, having access to safe, high quality birth facilities is critical. Early prenatal care, starting in the 1st trimester, is crucial to the health of mothers and babies. But more important than just initiating early prenatal care is receiving adequate prenatal care, having the appropriate number of prenatal care visits at the appropriate intervals throughout the pregnancy. Babies of mothers who do not get prenatal care are three times more likely to be born low birth weight and five times more likely to die than those born to mothers who do get care.1 In 2017 in Minnesota, only 77.1 percent of women received prenatal care within their first trimester of pregnancy. -

The Factors Affecting Amniocentesis Decision by Pregnant Women in the Risk Group and the Influence of Consultant

A L J O A T U N R I N R A E L P Original Article P L E R A Perinatal Journal 2019;27(1):6–13 I N N R A U T A L J O ©2019 Perinatal Medicine Foundation The factors affecting amniocentesis decision by pregnant women in the risk group and the influence of consultant Kanay Yararbafl1 İD , Ayflegül Kuflkucu2 İD 1Department of Medical Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, Ac›badem Mehmet Ali Ayd›nlar University, Istanbul, Turkey 2Department of Medical Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, Yeditepe University, Istanbul, Turkey Abstract Özet: Risk grubundaki gebelerin amniyosentez karar› almas›ndaki faktörler ve genetik dan›flman›n etkisi Objective: The most frequent goal for prenatal diagnosis is to Amaç: Do¤um öncesi tan›da günümüzde en s›k amaçlanan hedef detect pregnancies with Down syndrome. Since karyotyping, which Down sendromlu gebelikleri tespit etmektir. Tan›da alt›n standart is the golden standard for the diagnosis, has not been replaced with yöntem olan karyotiplemenin yerini henüz non-invaziv bir yön- a non-invasive method, pregnant women in the risk group should tem dolduramad›¤›ndan, CVS, amniyosentez gibi bir yöntem için choose the method such as CVS and amniocentesis. Therefore, risk alt›ndaki gebelerin seçimi gereklidir. Bu amaçla giriflimsel ol- screening tests are performed by non-invasive method, and preg- mayan yöntemlerle tarama testleri yap›lmakta, riskli gebelere ge- nant women under risk are provided genetic consultation and the netik dan›flma verilerek invaziv giriflim karar› aileye b›rak›lmakta- family is expected to make a decision for invasive procedure. -

Statement on Unassisted Birth Attended by a Doula

Statement On Unassisted Birth Attended by a Doula _______________________________________________________ Definition Unassisted childbirth – the process of intentionally giving birth without the assistance of a medical or professional birth attendant – is a decision made by a very small percentage of parents. DONA International certified and member doulas provide physical, informational and emotional support. Any type of medical or clinical assistance is outside the scope of practice agreed upon by DONA International certified and member doulas. DONA International opines herein on the considerations a doula must make when accepting clients planning an unassisted birth. Introduction Unassisted childbirth (UC) refers to the process of intentionally giving birth without the assistance of a medical or professional birth attendant. UC is also sometimes referred to as free birth, DIY (do-it-yourself) birth, unhindered birth and couples birth. In response to the recent growth in interest over UC, several national medical societies, including the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canadai, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologistsii, and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologistsiii, have issued strongly worded public statements warning against the practice. Professional midwives' associations, including the Royal College of Midwivesiv and the American College of Nurse-Midwivesv also caution against UC. Those who promote UCvi claim the practice offers mothers-to-be a natural way of welcoming their child into the world, free from drugs, machinery and medical intervention. They also note that UC allows a woman to listen to her body's signals rather than coaching from an outsider. The women who are choosing UC may do so because they do not feel supported and respected in the obstetrical care facilities available in their areas, or they are unable to afford or obtain home midwifery or physician support, which is more in line with their philosophies. -

Letter from ANA to the Office of National Coordinator for Health IT

November 6, 2015 Karen DeSalvo, MD, MPH, MSc National Coordinator Office of National Coordinator for Health IT Department of Health and Human Services 200 Independence Ave, SW Washington, DC 20201 Re: Comments on 2016 Interoperability Standards Advisory Best Available Standards and Implementation Specifications Submitted via: https://www.healthit.gov/standards-advisory/2016 Dear Dr. DeSalvo: The American Nurses Association (ANA) welcomes the opportunity to provide comments on the document “2016 Interoperability Standards Advisory Best Available Standards and Implementation Specifications.” As the only full-service professional organization representing the interests of the nation’s 3.4 million registered nurses (RNs), ANA is privileged to speak on behalf of its state and constituent member associations, organizational affiliates, and individual members. RNs serve in multiple direct care, care coordination, and administrative leadership roles, across the full spectrum of health care settings. RNs provide and coordinate patient care, educate patients, their families and other caregivers as well as the public about various health conditions, wellness, and prevention, and provide advice and emotional support to patients and their family members. ANA members also include the four advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) roles: nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, certified nurse-midwives and certified registered nurse anesthetists.1 We appreciate the efforts of the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology -

History of Midwifery in the US Parkland Memorial Hospital

History of Midwifery in the US Parkland Memorial Hospital Parkland School of Nurse Midwifery History of Midwifery in the US [Download this file in Text Format] Midwifery in the United States Native Americans had midwives within their various tribes. Midwifery in Colonial America began as an extension of European practices. It was noted that Brigit Lee Fuller attended three births on the Mayflower. Midwives filled a clear, important role in the colonies, one that Laurel Thatcher Ulrich explored in her Pulitzer Prize winning book: A Midwife's Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard Based on Her Diary 1785-1812. (Published in 1990). Midwifery was seen as a respectable profession, even warranting priority on ferry boats to the Colony of Massachusetts. Well skilled practitioners were actively sought by women. However, the apprentice model of training still predominated. A few private tutoring courses such as those offered by Dr. William Shippman, Jr. of Philadelphia existed, but were rare. The Midwifery Controversy The scientific nature of the nineteenth century education enabled an expansive knowledge explosion to occur in medical schools. The formalized medical communities and universities not only facilitated scientific inquiry, but also communicated new information on a variety of subjects including Pasteur's theory of infectious diseases, Holmes' and Semmelweis' work on puerperal fever, and Lister's writings on antisepsis. Since midwifery practice generally remained on an informal level, knowledge of this sophistication was not disseminated within the midwifery profession. Indeed, medical advances in pharmacology, hygiene and other practices were implemented routinely in obstetrics, without integration into midwifery practices. The homeopathic remedies and traditions practiced by generations of midwives began to appear in stark contrast to more "modern" remedies suggested by physicians. -

Midwifery: a Career for Men in Nursing

Midwifery: A career for men in nursing It may not be a common path men take, but how many male midwives are there? By Deanna Pilkenton, RN, CNM, MSN, and Mavis N. Schorn, RN, CNM, PHD(C) Every year, faculty at Vanderbilt University School of there are so few men in this profession. In fact, these Nursing reviews applications to the school’s nurse- conversations often lead to the unanimous sentiment midwifery program. The applicants’ diversity is always that men shouldn’t be in this specialty at all. Scanning of interest. A wide spectrum of age is common. A pleas- the web and reviewing blog discussions on this topic ant surprise has been the gradual improvement in the confirms that it’s a controversial idea, even among Eethnic and racial diversity of applicants. Nevertheless, midwives themselves. male applicants are still rare. It’s common knowledge that the profession of nurs- Many people wonder if there’s such thing as a male ing is female dominated, and the challenges and com- midwife. There are male midwives; there just aren’t plexities of this have been explored at length. many of them. When the subject of men in midwifery is Midwifery, however, may be one of the most exclusive- discussed, it usually conjures up perplexed looks. The ly and disproportionately female specialties in the field very idea of men in midwifery can create quite a stir, of nursing and it’s time to acknowledge the presence of and most laypeople don’t perceive it as strange that male midwives, the challenges they face, and the posi- www.meninnursingjournal.com February 2008 l Men in Nursing 29 tive attributes they bring to the pro- 1697, is credited with innovations fession. -

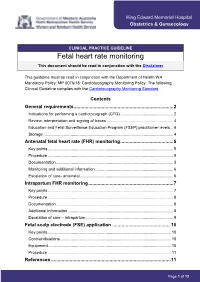

Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring This Document Should Be Read in Conjunction with the Disclaimer

King Edward Memorial Hospital Obstetrics & Gynaecology CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE Fetal heart rate monitoring This document should be read in conjunction with the Disclaimer This guideline must be read in conjunction with the Department of Health WA Mandatory Policy: MP 0076/18: Cardiotocography Monitoring Policy. The following Clinical Guideline complies with the Cardiotocography Monitoring Standard. Contents General requirements ........................................................................... 2 Indications for performing a cardiotocograph (CTG) ............................................... 2 Review, interpretation and signing of traces ........................................................... 4 Education and Fetal Surveillance Education Program (FSEP) practitioner levels ... 4 Storage ................................................................................................................... 4 Antenatal fetal heart rate (FHR) monitoring ........................................ 5 Key points ............................................................................................................... 5 Procedure ............................................................................................................... 5 Documentation ........................................................................................................ 5 Monitoring and additional information ..................................................................... 6 Escalation of care- antenatal .................................................................................. -

14. Management of Diabetes in Pregnancy: Standards of Medical

Diabetes Care Volume 42, Supplement 1, January 2019 S165 14. Management of Diabetes in American Diabetes Association Pregnancy: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetesd2019 Diabetes Care 2019;42(Suppl. 1):S165–S172 | https://doi.org/10.2337/dc19-S014 14. MANAGEMENT OF DIABETES IN PREGNANCY The American Diabetes Association (ADA) “Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes” includes ADA’s current clinical practice recommendations and is intended to provide the components of diabetes care, general treatment goals and guidelines, and tools to evaluate quality of care. Members of the ADA Professional Practice Committee, a multidisciplinary expert committee, are responsible for updating the Standards of Care annually, or more frequently as warranted. For a detailed description of ADA standards, statements, and reports, as well as the evidence-grading system for ADA’s clinical practice recommendations, please refer to the Standards of Care Introduction. Readers who wish to comment on the Standards of Care are invited to do so at professional.diabetes.org/SOC. DIABETES IN PREGNANCY The prevalence of diabetes in pregnancy has been increasing in the U.S. The majority is gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) with the remainder primarily preexisting type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes. The rise in GDM and type 2 diabetes in parallel with obesity both in the U.S. and worldwide is of particular concern. Both type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes in pregnancy confer significantly greater maternal and fetal risk than GDM, with some differences according to type of diabetes. In general, specific risks of uncontrolled diabetes in pregnancy include spontaneous abortion, fetal anomalies, preeclampsia, fetal demise, macrosomia, neonatal hypoglycemia, and neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, among others.