Article Two Or Three Months Later, Claiming That He Had Been Unable ₃₆ to find Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

V3N1 Newslet

Spring 2000; Volume 3 Issue 1 The New York LDS Historian Various Times and Sundry Places: Buildings Used by the LDS Church in Manhattan Written and Illustrated by Ned P. Thomas At the end of the 20th century, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is actively acquiring real estate and constructing new buildings for its expanding membership in New York City. The structures are a visible measure of the Church’s commitment to the city and seem to say that Latter-day Saints feel at home in New York. However, members haven’t always been so fortunate. Since the earliest days of the Church in the Free Thinkers to give a course of the city, members have searched for a lectures on Mormonism in Tammany home of their own, usually meeting in Hall, and soon the members had secured 2166 Broadway at 76th Street private homes and rented halls. A lull in “fifteen preaching places in the city, all (1928-1944) city church activity followed the west- of which were filled to overflow.3 ” ward trek in 1846 and 1847, and for most In 1840, Elders Brigham Young, Heber of the nineteenth century, no organized The New York LDS Historian branches met—at least so far as the C. Kimball, George A. Smith, and others is the quarterly newsletter of the New arrived in New York City en route to records show. But near the end of the York, New York Stake LDS History England as missionaries. They held nineteenth century, not long after the Committee. This newsletter contains Eastern States Mission was organized, many “precious meetings” with the articles about and notices of the research Saints, including a general Conference in Latter-day Saints began worshiping again of the Committee. -

Utah and the Mormons

Ken Sanders Rare Books Catalog 38 Terms Advance reservations are suggested. All items offered subject to prior sale. If item has already been sold, Buy Online link will show “Page Not Found.” Please call, fax, or e- mail to reserve an item. Our downtown Salt Lake City bookshop is open 10-6, Monday- Saturday. Voicemail, fax, or email is available to take your order 24 hours a day. All items are located at our store and are available for inspection during our normal business hours. Our 4,000 square foot store houses over 100,000 volumes of used, rare, and a smattering of new books. All items are guaranteed authentic and to be as described. All autographed items are guaranteed to be authentic. Any item may be returned for a full refund within ten days if the customer is not satisfied. Prior notification is appreciated. Prices are in U.S. Dollars. Cash with order. Regular customers and institutions may expect their usual terms. We accept cash, checks, wire transfers, Paypal, Visa, MasterCard and American Express. All items will be shipped via Fed-Ex ground unless otherwise requested. Shipping charges are $7.00 for the first item and $1.00 for each additional item. All other shipping, including expedited shipping and large items, will be shipped at cost. Utah residents, please add 6.85% Utah sales tax. Ken Sanders Rare Books 268 South 200 East Salt Lake City, Utah 84111 Tel. (801) 521-3819 Fax. (801) 521-2606 www.kensandersbooks.com email inquiries to: [email protected] [email protected] Entire contents copyright 2010 by Ken Sanders Rare Books, ABAA and may not be reprinted without permission. -

Joseph Smith and the Manchester (New York) Library

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 22 Issue 3 Article 6 7-1-1982 Joseph Smith and the Manchester (New York) Library Robert Paul Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Paul, Robert (1982) "Joseph Smith and the Manchester (New York) Library," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 22 : Iss. 3 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol22/iss3/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Paul: Joseph Smith and the Manchester (New York) Library joseph smith and the manchester new york library robert paul in a recent work on mormon origins it was again suggested that joseph smith may have derived some of his religious and theological ideas from the old manchester rental library a circulating library located within five miles of the smith family farm 1 this claim has received wide circulation but it has never really received the serious critical consideration it merits this paper attempts to assess the man- chester library its origin content current disposition and possible usefulness to joseph smith and others prior to the organization of the church in 1830 the manchester library was organized around 1812 and was orig- inally called the farmington library since at this early time the village of manchester as an unincorporated entity -

Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Heber J.Grant

TEACHINGS OF PRESIDENTS OF THE CHURCH HEBER J. GRANT TEACHINGS OF PRESIDENTS OF THE CHURCH HEBER J.GRANT Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah Your comments and suggestions about this book would be appreciated. Please submit them to Curriculum Planning, 50 East North Temple Street, Floor 24, Salt Lake City, UT 84150-3200 USA. E-mail: [email protected] Please list your name, address, ward, and stake. Be sure to give the title of the book. Then offer your comments and suggestions about the book’s strengths and areas of potential improvement. © 2002 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America English approval: 1/00 Contents Title Page Introduction . v Historical Summary . viii The Life and Ministry of Heber J. Grant . x 1 Learning and Teaching the Gospel . 1 2 The Mission of the Prophet Joseph Smith . 11 3 Walking in the Path That Leads to Life Eternal . 23 4 Persistence . 33 5 Comfort in the Hour of Death . 43 6 Uniting Families through Temple and Family History Work . 51 7 Personal, Abiding Testimony . 63 8 Following Those Whom God Has Chosen to Preside . 71 9 The Joy of Missionary Work . 83 10 The Power of Example . 92 11 Priesthood, “the Power of the Living God” . 101 12 Work and Self-Reliance . 109 13 Principles of Financial Security . 119 14 “Come, Come, Ye Saints” . 129 15 Labor for the Happiness of Others . 139 16 Forgiving Others . 147 17 Being Loyal Citizens . 157 18 The Song of the Heart . -

Religious Disaffiliation of the Second-Generation from Alternative Religious Groups

268 University of Alberta Religious Disaffiliation of the Second-Generation from Alternative Religious Groups by Stacey Gordey © A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology Edmonton, Alberta Fall 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-46959-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-46959-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

RICK GRUNDER — BOOKS Mormon List Sixty-Six

RICK GRUNDER — BOOKS Box 500, Lafayette, New York 13084-0500 – (315) 677-5218 www.rickgrunder.com ( email: [email protected] ) JANUARY 2010 Mormon List Sixty-Six NO-PICTURES VERSION, for dial-up Internet Connections This is my first page-format catalog in nearly ten years (Mormon List 65 was sent by post during August 2000). While only a .pdf document, this new form allows more illustrations, as well as links for easy internal navigation. Everything here is new (titles or at least copies not listed in my offerings before). Browse like usual, or click on the links below to find particular subjects. Enjoy! ________________________________________ LINKS WILL NOT WORK IN THIS NO-PICTURES VERSION OF THE LIST. Linked References below are to PAGE NUMBERS in this Catalog. 1830s publications, 10, 21 Liberty Jail, 8 polygamy, 31, 50 Babbitt, Almon W., 18 MANUSCRIPT ITEMS, 5, 23, 27, re-baptism for health, 31 Book of Mormon review, 13 31, 40, 57, 59 Roberts, B. H., 32 California, 3 map, 16 Sessions family, 50 Carrington, Albert, 6 McRae, Alexander, 7 Smith, Joseph, 3, 7, 14, 25, 31 castration, 55 Millennial Star, 61 Smoot Hearings, 31 children, death of, 3, 22, 43 Missouri, 7, 21 Snow, Eliza R., 57 Clark, Ezra T., 58 Mormon parallels, 33 Susquehanna County, crime and violence, 2, 3, 10 Native Americans, 9, 19 Pennsylvania, 35 16, 21, 29, 36, 37, 55 Nauvoo Mansion, 46 Tanner, Annie C., 58 D&C Section 27; 34 Nauvoo, 23, 39, 40, 45 Taylor, John, 40, Deseret Alphabet, 9, 61 New York, 10, 24 Temple, Nauvoo, 47 Forgeus, John A., 40 Nickerson, Freeman, 49 Temple, Salt Lake, 52 Gunnison, J. -

The Politics of Proselytizing: Europe After 1848 and the Development of Mormon Pre-Millenialism

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 5-2016 The Politics of Proselytizing: Europe after 1848 and the Development of Mormon Pre-Millenialism Jacob G. Bury Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Part of the Mormon Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bury, Jacob G., "The Politics of Proselytizing: Europe after 1848 and the Development of Mormon Pre- Millenialism" (2016). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 817. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/817 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “The Politics of Proselytizing: Europe after 1848 and the Development of Mormon Pre-Millennialism” Jacob G. Bury 1 In the second year of his reign as King of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, Nebuchadnezzar II dreamt of a large stone that rolled down the side of a mountain, shattered a great metallic statue, and grew into a mountain range large enough to cover the earth. The accomplished ruler, who went on to oversee the construction of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, as well as the destruction of Jerusalem’s Jewish temple, was no revelator, and so enlisted Daniel, an exiled Jew, to interpret his dream. According to Daniel, the statue, divided into five parts from head to toe, portrayed mankind’s present and future kingdoms. The last, represented by the statue’s iron and clay feet, would be “a divided kingdom.” Unable to unify, “the kingdom will be partly strong and partly brittle. -

Guide to State Statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection

U.S. CAPITOL VISITOR CENTER GUide To STATe STATUes iN The NATioNAl STATUArY HAll CollecTioN CVC 19-107 Edition V Senator Mazie Hirono of Hawaii addresses a group of high school students gathered in front of the statue of King Kamehameha in the Capitol Visitor Center. TOM FONTANA U.S. CAPITOL VISITOR CENTER GUide To STATe STATUes iN The NATioNAl STATUArY HAll CollecTioN STATE PAGE STATE PAGE Alabama . 3 Montana . .28 Alaska . 4 Nebraska . .29 Arizona . .5 Nevada . 30 Arkansas . 6 New Hampshire . .31 California . .7 New Jersey . 32 Colorado . 8 New Mexico . 33 Connecticut . 9 New York . .34 Delaware . .10 North Carolina . 35 Florida . .11 North Dakota . .36 Georgia . 12 Ohio . 37 Hawaii . .13 Oklahoma . 38 Idaho . 14 Oregon . 39 Illinois . .15 Pennsylvania . 40 Indiana . 16 Rhode Island . 41 Iowa . .17 South Carolina . 42 Kansas . .18 South Dakota . .43 Kentucky . .19 Tennessee . 44 Louisiana . .20 Texas . 45 Maine . .21 Utah . 46 Maryland . .22 Vermont . .47 Massachusetts . .23 Virginia . 48 Michigan . .24 Washington . .49 Minnesota . 25 West Virginia . 50 Mississippi . 26 Wisconsin . 51 Missouri . .27 Wyoming . .52 Statue photography by Architect of the Capitol The Guide to State Statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection is available as a free mobile app via the iTunes app store or Google play. 2 GUIDE TO STATE STATUES IN THE NATIONAL STATUARY HALL COLLECTION U.S. CAPITOL VISITOR CENTER AlabaMa he National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol is comprised of statues donated by individual states to honor persons notable in their history. The entire collection now consists of 100 statues contributed by 50 states. -

John Taylor's Introduction of the Sugar Beet Industry in Deseret

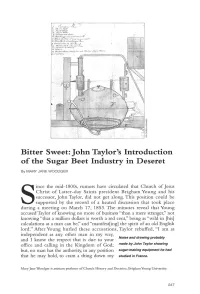

Bitter Sweet: John Taylor's Introduction of the Sugar Beet Industry in Deseret By MARY JANE WOODGER ince the mid-1800s, rumors have circulated that Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints president Brigham Young and his successor, John Taylor, did not get along. This position could be supported by the record of a heated discussion that took place Sduring a meeting on March 17, 1853. The minutes reveal that Young accused Taylor of knowing no more of business "than a mere stranger," not knowing "that a million doUars is worth a red cent," being as "wild in [his] calculations as a man can be," and "manifest[ing] the spirit of an old English lord." After Young hurled these accusations, Taylor rebuffed, "I am as independent as any other man in my way, and I know the respect that is due to your Notes and drawing probably office and calling in the Kingdom of God; made by John Taylor showing but, no man has the authority, in any position sugar-making equipment he had that he may hold, to cram a thing down my studied in France. Mary Jane Woodger is assistant professor of Church History and Doctrine, Brigham Young University. 247 UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY throat that is not so."1 The story that brought this argument to a head began in 1849. During the church's general conference in October, Young called forty-two-year- old Taylor to open France to the spreading of the Mormon gospel, translate the Book of Mormon into French, and look for "new ideas, new enterpris es, and new establishments.. -

The Life and Thought of Mormon Apostle Parley Parker Pratt

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 7-22-2013 The Life and Thought of Mormon Apostle Parley Parker Pratt Andrew James Morse Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the History of Religion Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Morse, Andrew James, "The Life and Thought of Mormon Apostle Parley Parker Pratt" (2013). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 1084. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.1084 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Life and Thought of Mormon Apostle Parley Parker Pratt by Andrew James Morse A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: David Johnson, Chair John Ott David Horowitz Natan Meir Portland State University 2013 © 2013 Andrew James Morse i ABSTRACT In 1855 Parley P. Pratt, a Mormon missionary and member of the Quorum of the Twelve, published Key to the Science of Theology . It was the culmination of over twenty years of intellectual engagement with the young religious movement of Mormonism. The book was also the first attempt by any Mormon at writing a comprehensive summary of the religion’s theological ideas. Pratt covered topics ranging from the origins of theology in ancient Judaism, the apostasy of early Christianity, the restoration of correct theology with nineteenth century Mormonism, dreams, polygamy, and communication with beings on other planets. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 14, 1988

Journal of Mormon History Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 1 1988 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 14, 1988 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1988) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 14, 1988," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 14 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol14/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 14, 1988 Table of Contents • --The Popular History of Early Victorian Britain: A Mormon Contribution John F. C. Harrison, 3 • --Heber J. Grant's European Mission, 1903-1906 Ronald W. Walker, 17 • --The Office of Presiding Patriarch: The Primacy Problem E. Gary Smith, 35 • --In Praise of Babylon: Church Leadership at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London T. Edgar Lyon Jr., 49 • --The Ecclesiastical Position of Women in Two Mormon Trajectories Ian G Barber, 63 • --Franklin D. Richards and the British Mission Richard W. Sadler, 81 • --Synoptic Minutes of a Quarterly Conference of the Twelve Apostles: The Clawson and Lund Diaries of July 9-11, 1901 Stan Larson, 97 This full issue is available in Journal of Mormon History: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol14/iss1/ 1 Journal of Mormon History , VOLUME 14, 1988 Editorial Staff LOWELL M. DURHAM JR., Editor ELEANOR KNOWLES, Associate Editor MARTHA SONNTAG BRADLEY, Associate Editor KENT WARE, Designer LEONARD J. -

Utah History Encyclopedia

PAINTING AND SCULPTURE IN UTAH Avard Fairbanks with models for "Pony Express" William W. Major (1804-1854) was the first Mormon painter to arrive in Utah (in 1848). From Great Britain, he spent five years headquartered in Great Salt Lake City painting portraits and making visits to various locations in the surrounding area in order to paint both landscapes and the faces of other settlers as well as of leaders among the indigenous Native American tribes. Meanwhile, virtually everything in the city of Salt Lake that could be in any way called sculpture was created by either the British woodcarver Ralph Ramsay (1824-1905) or the British stonecarver William Ward (1827-93). The three most significant pioneer painters were Danquart Weggeland (1827-1918), a Norwegian; C.C.A. Christensen (1831-1912), a Dane; and George M. Ottinger (1833-1917), originally from Pennsylvania. Christensen′s greatest achievement was the painting of numerous somewhat awkward but charming scenes showing episodes either from early Mormon history or from the Book of Mormon. Like Christensen, neither Ottinger nor Weggeland had much formal artistic training, but each produced a few somewhat more sophisticated figure and landscape paintings and advised their students to go east where they could study in Paris. Certainly, that is what Deseret′s young sculpture students would do; Parisian training played a major role in the artistic evolution of famed romantic realist bronze sculptor Cyrus E. Dallin (1861-1944), of Springville, Utah, as well as in that of Mt. Rushmore′s sculptor, Gutzun Borglum (1867-1941) and his talented brother, Solon Borglum (1868 1922), both of Ogden, Utah.