Rift Valley Fever, Mayotte, 2007–2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

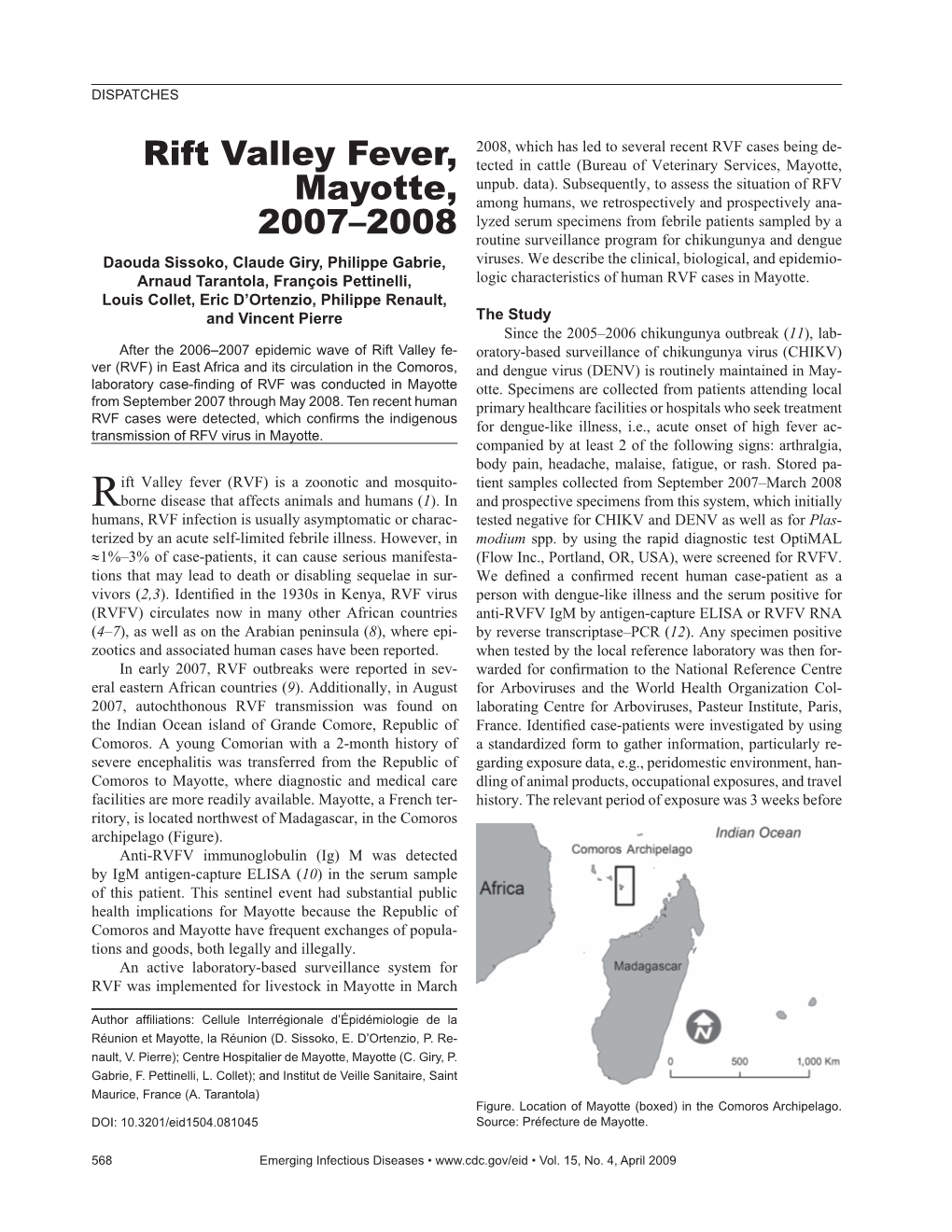

Recommended publications

-

Notice Générale Et Particulière Des Atlas

Mise à jour de l’aléa mouvements de terrain pour les atlas des aléas naturels, sur 8 communes de Mayotte Communes de Chiconi, Chirongui et Ouangani Rapport BRGM/RP-55589-FR Juillet 2007 Mise à jour de l’aléa mouvements de terrain pour les atlas des aléas naturels, sur 8 communes de Mayotte Communes de Chiconi, Chirongui et Ouangani Rapport BRGM/RP-55589-FR Juillet 2007 J.-C. Audru et M. Imbault Vérificateur Approbateur Nom : Nom : Date : Date : Signature : Signature : (Ou Original signé par) (Ou Original signé par) Le système de management de la qualité du BRGM est certifié AFAQ ISO 9001:2000. Mots clés : atlas, aléas naturels, mouvements de terrain, Mayotte, Comores En bibliographie, ce rapport sera cité de la façon suivante : J.-C. Audru et M. Imbault (2007) : Mise à jour de l’aléa mouvements de terrain pour les atlas des aléas naturels, sur 8 communes de Mayotte. Rapport BRGM/RP-55589-FR, 10 p., 9 figures. © BRGM, 2007, ce document ne peut être reproduit en totalité ou en partie sans l'autorisation expresse du BRGM. Mise à jour de l’aléa MVT pour huit atlas des aléas naturels à Mayotte _ Chiconi, Chirongui et Ouangani LaLa misemise àà jour jour dede l’aléal’aléa MVTMVT CONTEXTE ET OBJECTIFS DE L’ÉTUDE Trois niveaux d'aléa ont ainsi été déterminés : De 2001 à 2006, le BRGM a réalisé les atlas des aléas naturels à Mayotte. Pour les mouvements de terrain, ces atlas avaient été cartographiés à 1/10 000 dans les zones urbaines (suivant leur 1 = nul à faible : cela qualifie les zones dans lesquelles ne peuvent se manifester que des extension en 2002), alors que les zones rurales de l’époque avaient été cartographiées à 1/25 000. -

Dengue Fever and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever (Dhf)

DENGUE FEVER AND DENGUE HEMORRHAGIC FEVER (DHF) What are DENGUE and DHF? Dengue and DHF are viral diseases transmitted by mosquitoes in tropical and subtropical regions of the world. Cases of dengue and DHF are confirmed every year in travelers returning to the United States after visits to regions such as the South Pacific, Asia, the Caribbean, the Americas and Africa. How is dengue fever spread? Dengue virus is transmitted to people by the bite of an infected mosquito. Dengue cannot be spread directly from person to person. What are the symptoms of dengue fever? The most common symptoms of dengue are high fever for 2–7 days, severe headache, backache, joint pains, nausea and vomiting, eye pain and rash. The rash is frequently not visible in dark-skinned people. Young children typically have a milder illness than older children and adults. Most patients report a non-specific flu-like illness. Many patients infected with dengue will not show any symptoms. DHF is a more severe form of dengue. Initial symptoms are the same as dengue but are followed by bleeding problems such as easy bruising, skin hemorrhages, bleeding from the nose or gums, and possible bleeding of the internal organs. DHF is very rare. How soon after exposure do symptoms appear? Symptoms of dengue can occur from 3-14 days, commonly 4-7 days, after the bite of an infected mosquito. What is the treatment for dengue fever? There is no specific treatment for dengue. Treatment usually involves treating symptoms such as managing fever, general aches and pains. Persons who have traveled to a tropical or sub-tropical region should consult their physician if they develop symptoms. -

Population Légales 15 Nov IMI

POPULATION N° 61 - Novembre 2012 Recensement : 212 600 habitants à Mayotte en 2012 La population augmente toujours fortement Depuis 2007, la population de Mayotte augmente fortement, à un rythme moyen de 2,7 % par an. Elle atteint 212 600 habitants en août 2012. Avec 570 habitants au km2, Mayotte est le département français le plus dense après ceux d'Île-de-France. Un Mahorais sur deux vit au Nord-est de l’île. Depuis 2007, les communes de Ouangani et Koungou croissent le plus vite. En revanche, le centre ville de Mamoudzou perd des habitants alors que la périphérie se développe. Le nombre de logements progresse un peu moins vite que la population. En août 2012, 212 645 personnes vivent à Mayotte. Un Mahorais sur deux vit La population de Mayotte a augmenté de 26 200 dans le Nord-est de l’île habitants depuis 2007, soit 5 240 habitants de plus en moyenne chaque année. Près de la moitié de la population de Mayotte se concentre dans le Nord-est de l’île, sur les communes En très forte croissance depuis plusieurs décennies, de Petite Terre, de Koungou et de Mamoudzou. Com- la population mahoraise a triplé depuis 1985. Bien mune la plus peuplée de l’île, Mamoudzou compte que cette croissance reste soutenue depuis 2007 57 300 habitants en 2012, soit 27 % de la population (+ 2,7 % par an), elle ralentit comparativement aux mahoraise. Préfecture et capitale économique du périodes précédentes : + 5,7 % entre 1991 et 1997, département, Mamoudzou concentre sur son territoire + 4,1 % entre 1997 et 2002 et + 3,1 % entre 2002 et l’essentiel des administrations et de l’emploi. -

Dengue and Yellow Fever

GBL42 11/27/03 4:02 PM Page 262 CHAPTER 42 Dengue and Yellow Fever Dengue, 262 Yellow fever, 265 Further reading, 266 While the most important viral haemorrhagic tor (Aedes aegypti) as well as reinfestation of this fevers numerically (dengue and yellow fever) are insect into Central and South America (it was transmitted exclusively by arthropods, other largely eradicated in the 1960s). Other factors arboviral haemorrhagic fevers (Crimean– include intercontinental transport of car tyres Congo and Rift Valley fevers) can also be trans- containing Aedes albopictus eggs, overcrowding mitted directly by body fluids. A third group of of refugee and urban populations and increasing haemorrhagic fever viruses (Lassa, Ebola, Mar- human travel. In hyperendemic areas of Asia, burg) are only transmitted directly, and are not disease is seen mainly in children. transmitted by arthropods at all. The directly Aedes mosquitoes are ‘peri-domestic’: they transmissible viral haemorrhagic fevers are dis- breed in collections of fresh water around the cussed in Chapter 41. house (e.g. water storage jars).They feed on hu- mans (anthrophilic), mainly by day, and feed re- peatedly on different hosts (enhancing their role Dengue as vectors). Dengue virus is numerically the most important Clinical features arbovirus infecting humans, with an estimated Dengue virus may cause a non-specific febrile 100 million cases per year and 2.5 billion people illness or asymptomatic infection, especially in at risk.There are four serotypes of dengue virus, young children. However, there are two main transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes, and it is un- clinical dengue syndromes: dengue fever (DF) usual among arboviruses in that humans are the and dengue haemorrhagic fever (DHF). -

RP Mayotte.Vp

En cinq ans, 26 000 habitants de plus à Mayotte Au 31 juillet 2007, la e recensement général de la population de port à la période intercensitaire précédente LMayotte s’est déroulé du 31 juillet au 27 août (1997-2002). Il demeure largement supérieur à population de la collectivité 2007. Cette opération d’envergure, qui va per- ce qu’il est au niveau national ou même à La mettre de dresser le nouveau portrait de la popu- Réunion (respectivement 0,6 % et 1,5 % de taux départementale de Mayotte lation et de ses conditions de logement, a pour de croissance annuel moyen sur la période 1999- atteint 186 452 habitants. Son premier objectif de déterminer les chiffres de 2006). population des différentes circonscriptions admi- taux de croissance annuel nistratives de Mayotte. Ces chiffres, publiés et La densité de population de Mayotte passe en moyen a été moins élevé sur commentés fin novembre par l’antenne Insee de 2007 le seuil des 500 habitants par km². Avec Mayotte, ont été authentifiés par le décret 511 habitants par km², après 439 en 2002, elle la période 2002-2007 que par n° 2007-1885 du 26 décembre 2007 (paru au J.O se rapproche de la densité de l’île Maurice qui n° 303 du 30 décembre 2007). détient le record parmi les îles du Sud-ouest de le passé. Il demeure l’océan Indien avec 587 habitants au km2 en cependant important, Mayotte comptait 186 452 habitants au 31 juillet 2001. Les communes mahoraises les plus peu- 2007, date de référence du recensement. -

Florida Arbovirus Surveillance Week 13: March 28-April 3, 2021

Florida Arbovirus Surveillance Week 13: March 28-April 3, 2021 Arbovirus surveillance in Florida includes endemic mosquito-borne viruses such as West Nile virus (WNV), Eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV), and St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV), as well as exotic viruses such as dengue virus (DENV), chikungunya virus (CHIKV), Zika virus (ZIKV), and California encephalitis group viruses (CEV). Malaria, a parasitic mosquito-borne disease is also included. During the period of March 28- April 3, 2021, the following arboviral activity was recorded in Florida. WNV activity: No human cases of WNV infection were reported this week. No horses with WNV infection were reported this week. No sentinel chickens tested positive for antibodies to WNV this week. In 2021, positive samples from two sentinel chickens has been reported from two counties. SLEV activity: No human cases of SLEV infection were reported this week. No sentinel chickens tested positive for antibodies to SLEV this week. In 2021, no positive samples have been reported. EEEV activity: No human cases of EEEV infection were reported this week. No horses with EEEV infection were reported this week. No sentinel chickens tested positive for antibodies to EEEV this week. In 2021, positive samples from one horse and 14 sentinel chickens have been reported from four counties. International Travel-Associated Dengue Fever Cases: No cases of dengue fever were reported this week in persons that had international travel. In 2021, one travel-associated dengue fever case has been reported. Dengue Fever Cases Acquired in Florida: No cases of locally acquired dengue fever were reported this week. In 2021, no cases of locally acquired dengue fever have been reported. -

Combatting Malaria, Dengue and Zika Using Nuclear Technology by Nicole Jawerth and Elodie Broussard

Infectious Diseases Combatting malaria, dengue and Zika using nuclear technology By Nicole Jawerth and Elodie Broussard A male Aedes species mosquito. iseases such as malaria, dengue and transcription–polymerase chain reaction (Photo: IAEA) Zika, spread by various mosquito (RT–PCR) (see page 8). Experts across the Dspecies, are wreaking havoc on millions of world have been trained and equipped by lives worldwide. To combat these harmful the IAEA to use this technique for detecting, and often life-threatening diseases, experts tracking and studying pathogens such as in many countries are turning to nuclear and viruses. The diagnostic results help health nuclear-derived techniques for both disease care professionals to provide treatment and detection and insect control. enable experts to track the viruses and take action to control their spread. Dengue and Zika When a new outbreak of disease struck in The dengue virus and Zika virus are mainly 2015 and 2016, physicians weren’t sure of spread by Aedes species mosquitoes, which its cause, but RT–PCR helped to determine are most common in tropical regions. In most that the outbreak was the Zika virus and not cases, the dengue virus causes debilitating another virus such as dengue. RT–PCR was flu-like symptoms, but all four strains of the used to detect the virus in infected people virus also have the potential to cause severe, throughout the epidemic, which was declared life-threatening diseases. In the case of the Zika a public health emergency of international virus, many infected people are asymptomatic concern by the World Health Organization or only have mild symptoms; however, the virus (WHO) in January 2016. -

Dengue Fever (Breakbone Fever, Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever)

Division of Disease Control What Do I Need to Know? Dengue Fever (breakbone fever, dengue hemorrhagic fever) What is Dengue Fever? Dengue fever is a serious form of mosquito-borne disease caused one of four closely related viruses called Flaviviruses. They are named DENV 1, DENV 2, DENV 3, or DENV 4. The disease is found in most tropical and subtropical areas (including some islands in the Caribbean, Mexico, most countries of South and Central America, the Pacific, Asia, parts of tropical Africa and Australia). Almost all cases reported in the continental United States are in travelers who have recently returned from countries where the disease circulates. Dengue is endemic to the U.S. territories of Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and Guam and in recent years non-travel related cases have been found in Texas, Florida, and Hawaii. Who is at risk for Dengue Fever? Dengue fever may occur in people of all ages who are exposed to infected mosquitoes. The disease occurs in areas where the mosquitos that carry dengue circulate, usually during the rainy seasons when mosquito populations are at high numbers. What are the symptoms of Dengue Fever? Dengue fever is characterized by the rapid development of fever that may last from two to seven days, intense headache, joint and muscle pain and a rash. The rash develops on the feet or legs three to four days after the beginning of the fever. Some people with dengue develop dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF). Symptoms of DHF are characteristic of internal bleeding and include: severe abdominal pain, red patches on skin, bleeding from nose or gums, black stools, vomiting blood, drowsiness, cold and clammy skin and difficulty breathing. -

Prevent Dengue & Chikungunya

Prevent Dengue & Chikungunya WHO Myanmar newsletter special, 9 September 2019 What is dengue? Dengue situation in Myanmar Dengue is one of the most common mosquito- Cases and deaths 2015-2019 borne viral infections. The infection is spread from one person to another through the bite of infectious mosquitoes, either Aedes aegypti or Aedes albopictus. There are 4 distinct types of dengue virus, called DEN-1, DEN-2, DEN-3 and DEN-4. Dengue can be mild, as in most cases, or severe, as in few cases. It can cause serious illness and death among children. In Myanmar, July to August is peak season for transmission of dengue - coinciding with monsoon. How every one of us can help prevent dengue source: VBDC, Department of Public Health, Ministry of Health & Sports, 2019 z community awareness for mosquito breeding As shown above, dengue is cyclical in Myanmar, control is key alternating annually, as is the case in many countries. z cover, empty and clean domestic water storage At the same time, the number of dengue cases, and containers -- weekly is best deaths due to denge, over the period 2015 to 2018, z remove from the environment plastic bottles, both show a decreasing trend overall. plastic bags, fruit cans, discarded tyres -- for these are preferred mosquito breeding sites by Examples of how national and local authorities aedes aegypti (depicted) and aedes albopictus contribute z drain water collection points around the house z providing support for dengue management at z seek advice of a health professional if you have health facilities. multiple signs or symptoms of dengue z strengthening online reporting of dengue, How to recognize dengue? what are signs and using electronic based information system. -

A Look Into Bunyavirales Genomes: Functions of Non-Structural (NS) Proteins

viruses Review A Look into Bunyavirales Genomes: Functions of Non-Structural (NS) Proteins Shanna S. Leventhal, Drew Wilson, Heinz Feldmann and David W. Hawman * Laboratory of Virology, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Hamilton, MT 59840, USA; [email protected] (S.S.L.); [email protected] (D.W.); [email protected] (H.F.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-406-802-6120 Abstract: In 2016, the Bunyavirales order was established by the International Committee on Taxon- omy of Viruses (ICTV) to incorporate the increasing number of related viruses across 13 viral families. While diverse, four of the families (Peribunyaviridae, Nairoviridae, Hantaviridae, and Phenuiviridae) contain known human pathogens and share a similar tri-segmented, negative-sense RNA genomic organization. In addition to the nucleoprotein and envelope glycoproteins encoded by the small and medium segments, respectively, many of the viruses in these families also encode for non-structural (NS) NSs and NSm proteins. The NSs of Phenuiviridae is the most extensively studied as a host interferon antagonist, functioning through a variety of mechanisms seen throughout the other three families. In addition, functions impacting cellular apoptosis, chromatin organization, and transcrip- tional activities, to name a few, are possessed by NSs across the families. Peribunyaviridae, Nairoviridae, and Phenuiviridae also encode an NSm, although less extensively studied than NSs, that has roles in antagonizing immune responses, promoting viral assembly and infectivity, and even maintenance of infection in host mosquito vectors. Overall, the similar and divergent roles of NS proteins of these Citation: Leventhal, S.S.; Wilson, D.; human pathogenic Bunyavirales are of particular interest in understanding disease progression, viral Feldmann, H.; Hawman, D.W. -

Détails Des Vœux Géographiques Rappel Liste Des 11

[email protected]/[email protected] 1 bis Mouvement Intra Départemental_Avril 2020 / DPE1D Détails des vœux géographiques Rappel Liste des 11 circonscriptions ACOUA BANDRABOUA BOUENI ET KANI KELI DEMBENI DZAOUDZI (Petite-Terre) KOUNGOU MAMOUDZOU CENTRE MAMOUDZOU SUD MAMOUDZOU-NORD PETITE-TERRE SADA TSINGONI Vœux géographiques Circonscription : Écoles maternelles (ECMA) : 11 zones géographiques Circonscription : Écoles élémentaires (ECEL) : 11 zones géographiques Circonscription : Directeurs (DIR): 11 zones géographiques Circonscription : Ulis École {ASH} « ancienne CLIS » ULEC TFC (Option D), ULEC TFA (Option A), ULEC TFM (Option C) Circonscription : TR-ZIL (TIT.R.ZIL) : 11 zones géographiques 1 [email protected]/[email protected] 1 bis Mouvement Intra Départemental_Avril 2020 / DPE1D Détails des écoles concernant les vœux géographiques IEN Acoua Ces communes sont été définies en secteurs pour avoir les écoles relatives au regroupement IEN ACOUA : Secteur Acoua Secteur Mtzamboro 2 [email protected]/[email protected] 1 bis Mouvement Intra Départemental_Avril 2020 / DPE1D Secteur Mtsangamouji IEN Bandraboua Ces communes sont été définies en secteurs pour avoir les écoles relatives au regroupement IEN BANDRABOUA : Secteur Mtsangamboua 3 [email protected]/[email protected] 1 bis Mouvement Intra Départemental_Avril 2020 / DPE1D Secteur Bandraboua Secteur Dzoumogné Secteur Longoni 4 [email protected]/[email protected] 1 bis Mouvement Intra Départemental_Avril 2020 / DPE1D IEN Boueni & Kani-Keli Ces communes sont été définies -

Guiding Dengue Vaccine Development Using Knowledge Gained from the Success of the Yellow Fever Vaccine

Cellular & Molecular Immunology (2016) 13, 36–46 ß 2015 CSI and USTC. All rights reserved 1672-7681/15 $32.00 www.nature.com/cmi REVIEW Guiding dengue vaccine development using knowledge gained from the success of the yellow fever vaccine Huabin Liang, Min Lee and Xia Jin Flaviviruses comprise approximately 70 closely related RNA viruses. These include several mosquito-borne pathogens, such as yellow fever virus (YFV), dengue virus (DENV), and Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), which can cause significant human diseases and thus are of great medical importance. Vaccines against both YFV and JEV have been used successfully in humans for decades; however, the development of a DENV vaccine has encountered considerable obstacles. Here, we review the protective immune responses elicited by the vaccine against YFV to provide some insights into the development of a protective DENV vaccine. Cellular & Molecular Immunology (2016) 13, 36–46; doi:10.1038/cmi.2015.76 Keywords: dengue virus; protective immunity; vaccine; yellow fever INTRODUCTION from a viremic patient and is capable of delivering viruses to its Flaviviruses belong to the family Flaviviridae, which includes offspring, thereby amplifying the number of carriers of infec- mosquito-borne pathogens such as yellow fever virus (YFV), tion.6,7 Because international travel has become more frequent, Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), dengue virus (DENV), and infected vectors can be transported much more easily from an West Nile virus (WNV). Flaviviruses can cause human diseases endemic region to other areas of the world, rendering vector- and thus are considered medically important. According to borne diseases such as dengue fever a global health problem.