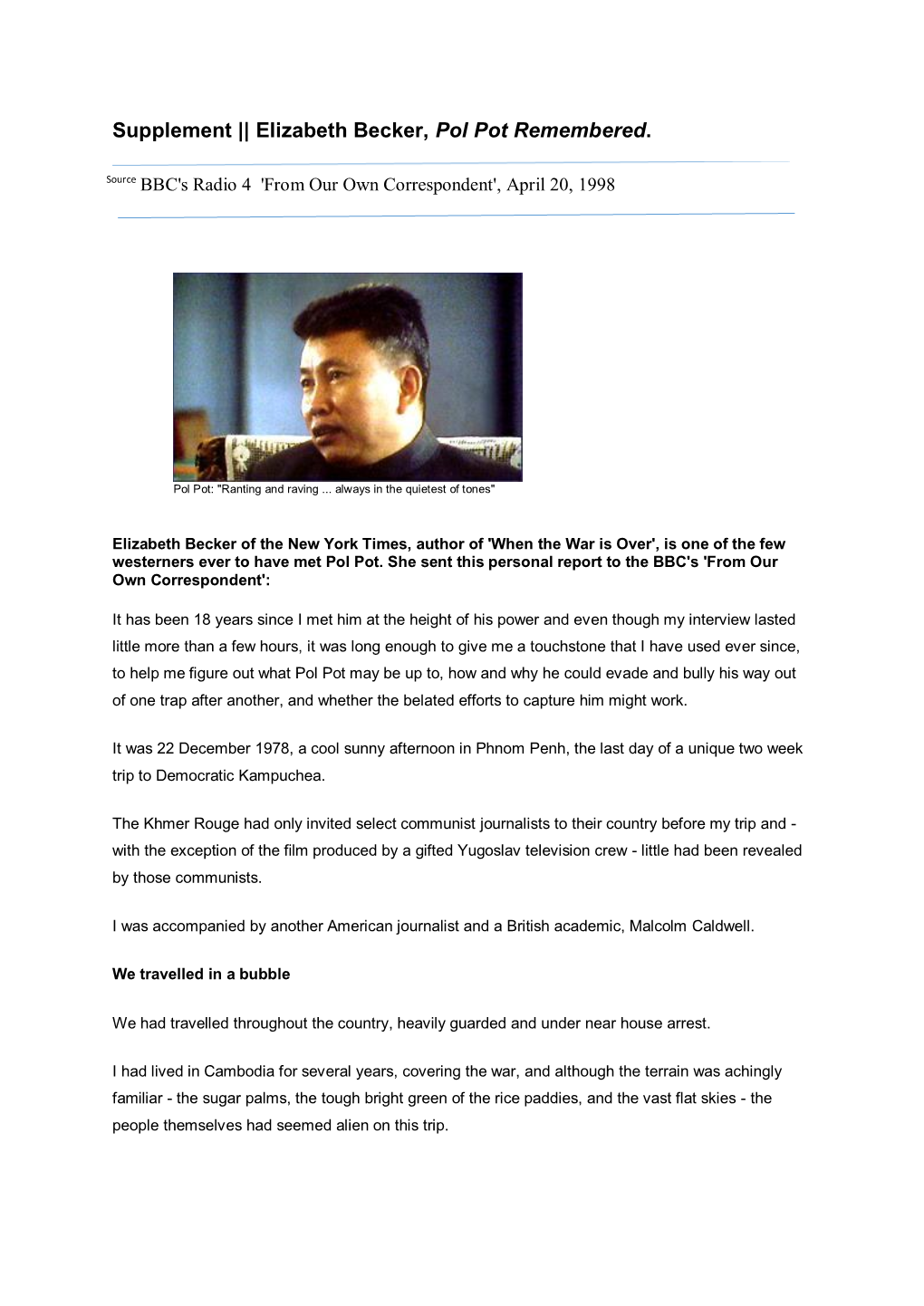

Supplement || Elizabeth Becker, Pol Pot Remembered

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minor Characters

August 28, 2005 New York Times Minor Characters By ELIZABETH BECKER The Tuol Sleng Museum, housed in the former KhmerRouge secret prison in Phnom Penh, is Cambodia's memorial to the nearly twomillion people who died during the genocidal reign of Pol Pot. Among all those victims, one woman's life -- and death-- has come to symbolize the horrors of the Khmer Rouge regime. Her name isHout Bophana, and her story is told in a movie shown twice a day at the museum.Sometimes called the Anne Frank of Cambodia, Bophana has become a folk heroine,known for the letters and confessions she wrote before her torture and murderby the Khmer Rouge. Every novelist knows that minor characters have a wayof taking over the narrative. But in the years since I first told her story inmy 1986 book, ''When the War Was Over,'' a history of modern Cambodia, Bophanahas taken on a life of her own and shown me the same thing can happen innonfiction. Then again, Bophana was overwhelming from the start. In the immediate years after the Vietnamese overthrewPol Pot, researchers got a first look at the hundreds of secret files kept atTuol Sleng. Our priority was to reconstruct the history of Pol Pot's regime,which forced confessions of key political figures. But I also searched foraverage Cambodians, people whose individual stories could illuminate the largertragedy. When I unearthed Bophana's file in 1981, my stomach dropped. Thedossier was filled with love letters. In the middle of one of the 20thcentury's worst instances of mass murder, here was a beautiful young womansecretly writing love letters to her husband, knowing full well that in theclosed Khmer dictatorship, she would be killed if they were found. -

ECCC, Case 002/01, Issue 52

KRT TRIAL MONITOR Case 002 ■ Issue No. 52 ■ Hearing on Evidence Week 47 ■ 5 and 7 February2013 Case of Nuon Chea, Khieu Samphan and Ieng Sary Asian International Justice Initiative (AIJI), a project of East-West Center and UC Berkeley War Crimes Studies Center * And if you, the Accused, are willing to conduct your self-criticism, you would clearly see the undeniable result through invaluable and countless evidence… And that is the mass crimes committed by the revolutionary Angkar.1 - Civil Party Pin Yathay I. OVERVIEW This week the Court held only two days of hearing due to the health status of Nuon Chea. The Chamber announced that the Accused, who had been released from Khmer-Soviet Friendship Hospital the previous Thursday, had to be readmitted the following Saturday. Therefore, this week’s proceedings only addressed issues that did not pertain to his case, or certain specific topics for which he had waived his right to attend, namely the continuation of document presentation on Khieu Samphan’s role in the DK regime2 and the hearing of Civil Party Pin Yathay’s testimony. The documents presented on Tuesday shed further light on the ideological leaning of Khieu Samphan, his involvement in CPK’s Standing Committee, and the degree of his role in and knowledge of the disastrous agricultural policies of the regime, the purging, and the massacres. On Thursday, Pin Yathay took the stand and testified on his experience throughout the first and second wave of evacuation during the Democratic Kampuchea period before he absconded to Thailand in 1977. II. SUMMARY OF CIVIL PARTY TESTIMONY Pin Yathay was born in 9 March 1944. -

1973 - August 1974

£cx?N.Mlc \MPUcfifCtoNS THE LIMITS TO STABILITY: THE AE3ERMAT-H OF THE PARIS AGREEMENT ON VIETNAM, JANUARY 1973 - AUGUST 1974. YVONNE TAN PHD. THESIS UNIVERSITY OF LONDON (EXTERNAL) 1991. 1 ProQuest Number: 11015921 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015921 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT ECONOMIC (MPUcAHws THE LIMITS TO STABILITY : THE AFTERMATH OF THE PARIS AGREEMENT ON VIETNAM, JANUARY 1973 - AUGUST 1974. The Paris Agreement of 27 January 1973 was intended, at least by some of its authors, to end the war and to bring peace to Vietnam and Indochina. Studies on the Agreement have gen erally focused on the American retreat from Vietnam and the military and political consequences leading to the fall of Saigon in April 1975. This study will seek to explore a number of questions which remain controversial. It addresses itself to considering whether under the circumstances prevailing between 1973 and 1974 the Paris Agreement could have worked. In the light of these circum stances it argues that the Agreement sought to establish a frame work for future stability and economic development through multilateral aid and rehabilitation aimed at the eventual survival of South Vietnam. -

British Leyland Wield Axe to Boost Profits

S STRUGGLEI POLITICAL PAPER OF T o ..• ~ o . l9 September 20th to October 3rd fortnightly 7p BRITISH LEYLAND WIELD AXE TO BOOST PROFITS In another savage attack on jobs, British Leyland's combined resources and planning will be a po-werful wh izz-kid Sir Michael Edwardes has announced a new competitor f or Peugot Citroen, Fiat, Ford, General package of cut-backs. A further 25,000 workers will ~o tors etc . But the market is shrinking and the lose their jobs over the next two years . This is on break-neck rivalry between the car giants t o pro top of the 18,000 jobs lost in the past year. The duce mor e and cheaper cars is deepening the crisis extent of closure and destruction of factories and of over-production. machinery is staggering. The Park Royal Titan Bu s Plant is to be closed. Aveling Marshall a t Ga ins CA PITALIST CRI SIS TO BLAME borough in Linconshire where special products are made is to be closed by the end of Octo1er . Car The press bar ons ar e busy blaming the workers for a ssembly will cease at Ganley in Coventry and Leylands cut- backs. I n its "Mirror Comment" the Abingdon, Berkshire. (The need to move the TR7 Daily Mirror put up a show of blaming workers and Triumph plant in Speke, Liverpool nearer the Gan ley managemen t. Bu t they saved their most acid comments assembly plant, was one of the reasons used t o f or the wo r kers. justify sacking thousands of the TR7 Speke wo r kers. -

Ggácmnmucrmhvisambaøkñú

01065520 E1/259.1 ŪĮйŬď₧şŪ˝˝ņįО ď ďijЊ ⅜₤Ĝ ŪĮйņΉ˝℮Ūij GgÁCMnMuCRmHvisamBaØkñúgtulakarkm <úCa Kingdom of Cambodia Nation Religion King Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia Royaume du Cambodge Chambres Extraordinaires au sein des Tribunaux Cambodgiens Nation Religion Roi Β₣ðĄеĕНеĄŪņй⅜ŵřеĠР₣ Trial Chamber Chambre de première instance TRANSCRIPT OF TRIAL PROCEEDINGS PUBLIC Case File Nº 002/19-09-2007-ECCC/TC 9 February 2015 Trial Day 240 Before the Judges: NIL Nonn, Presiding The Accused: NUON Chea YA Sokhan KHIEU Samphan Claudia FENZ Jean-Marc LAVERGNE YOU Ottara Lawyers for the Accused: Martin KAROPKIN (Reserve) Victor KOPPE THOU Mony (Reserve) SUON Visal KONG Sam Onn Anta GUISSÉ Trial Chamber Greffiers/Legal Officers: SE Kolvuthy Roger PHILLIPS Lawyers for the Civil Parties: Marie GUIRAUD LOR Chunthy For the Office of the Co-Prosecutors: VEN Pov Nicolas KOUMJIAN SENG Leang Dale LYSAK For Court Management Section: UCH Arun SOUR Sotheavy 01065521 E1/259.1 Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia Trial Chamber – Trial Day 240 Case No. 002/19-09-2007-ECCC/TC 9/02/2015 I N D E X MS. ELIZABETH BECKER (2-TCE-97) Questioning by the President .......................................................................................................... page 3 Questioning by Judge Lavergne ................................................................................................... page 10 Questioning by Mr. Seng Leang ................................................................................................... page 66 Questioning by Mr. Koumjian ........................................................................................................ page 82 Page i 01065522 E1/259.1 Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia Trial Chamber – Trial Day 240 Case No. 002/19-09-2007-ECCC/TC 9/02/2015 List of Speakers: Language used unless specified otherwise in the transcript Speaker Language MS. BECKER (2-TCE-97) English MR. -

Curriculum Vitae: Ben Kiernan Full Name: Benedict Francis Kiernan

Curriculum Vitae: Ben Kiernan Full Name: Benedict Francis Kiernan Place and East Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Date of Birth: 29 January 1953. Address: Department of History, Yale University, P.O. Box 208324, New Haven, CT 06520-8324, USA. Employment 1975-1977 Tutor in History, University of New South Wales History: 1978-1982 Postgraduate student, History, Monash University 1983 Research Fellow, Ethnic Studies, Australian Institute of Multicultural Affairs. 1984-1985 Post-doctoral Fellow, History, Monash University. 1986-1987 Lecturer in History, University of Wollongong. 1988-1990 Senior Lecturer, Department of History and Politics, University of Wollongong (with tenure, 1989). 1990-97 Associate Professor of History, Yale University. 1994-99 Founding Director, Cambodian Genocide Program, (http://gsp.yale.edu/case-studies/cambodian-genocide-program) 1997-99 Professor of History, Yale University. 1998-2015 Founding Director, Genocide Studies Program, Yale University (http://gsp.yale.edu) 1999- A.Whitney Griswold Professor of History, Yale University. 2000-02 Convenor, Yale East Timor Project. 2003-08 Honorary Professorial Fellow, University of Melbourne. 2005- Professor of International and Area Studies, Yale University. 2010-15 Chair, Council on Southeast Asia Studies, Yale University. Formal Academic B.A. (Hons), 1st Class, History, Monash University, 1975. Qualifications: Thesis: ‘The Samlaut Rebellion and Its Aftermath, 1967-70: The Beginnings of the Modern Cambodian Resistance’ (131 pp.) Ph.D. in History, Monash University, 1983. Dissertation: ‘How Pol Pot Came to Power: A History of Communism in Kampuchea, 1930-1975’ (579 pp.) Positions Held: Member of the Editorial Boards of Critical Asian Studies (formerly Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars), 1983- ; Human Rights Review, 1999- ; TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia, 2012- ; Zeitschrift für Genozidforschung, 2004- ; Journal of Genocide Research, 1999-2008; Genocide Studies and Prevention, 2006-9; Journal of Human Rights, 2001-7. -

Prosecuting the Khmer Rouge Views from the Inside

Prosecuting the Khmer Rouge Views from the Inside Content 1 Introduction Ratana Ly 2 Historical Background 3 The ECCC 4 The Different Actor Groups and their Relations to the ECCC 5 Patterns, Dynamics, Drivers of Acceptance and Rejection of the ECCC 6 Conclusion Prosecuting the Khmer Rouge: Views from the Inside Prosecuting the Khmer Rouge: Views from the Inside Ratana Ly1 ‘Justice, peace and democracy are not mutually exclusive objectives, but rather mutually reinforcing imperatives’ (United Nations Secretary General 2004). 1. Introduction Out of Cambodia’s total population of approximately 7 to 8 million, it is estimated that 1.5 to 2 million died of starvation, disease, and execution during the reign of the Democratic Kampuchea (DK) regime, which lasted from 17 April 1975 to 6 January 1979 (Kiernan 1996, 456-460). Following the fall of the DK (also known as the Khmer Rouge Regime), ‘a truth commission, lustration policies, amnesty programmes, and domestic or international trials were all considered or attempted’ to provide justice and peace for Cambodians (Ciorciari and Heindel 2014, 14). Out of these responses, the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), a hybrid court established jointly by Cambodia and the United Nations (UN) is the only internationally recognised judicial mechanism established to address Khmer Rouge crimes.2 The ECCC is, however, the product of a political compromise, resulting from protracted negotiations between the Cambodian government and the UN, whose relationship was characterised by ‘bitter -

Proquest Dissertations

RICE UNIVERSITY Tracing the Last Breath: Movements in Anlong Veng &dss?e?73&£i& frjjrarijsfass cassis^ scesse & w o O as by Timothy Dylan Wood A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE: y' 7* Stephen A. Tyler, Herbert S. Autrey Professor Department of Philip R. Wood, Professor Department of French Studies HOUSTON, TEXAS MAY 2009 UMI Number: 3362431 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3362431 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT Tracing the Last Breath: Movements in Anlong Veng by Timothy Dylan Wood Anlong Veng was the last stronghold of the Khmer Rouge until the organization's ultimate collapse and defeat in 1999. This dissertation argues that recent moves by the Cambodian government to transform this site into an "historical-tourist area" is overwhelmingly dominated by commercial priorities. However, the tourism project simultaneously effects an historical narrative that inherits but transforms the government's historiographic endeavors that immediately followed Democratic Kampuchea's 1979 ousting. -

The Khmer Rouge Practice of Thought Reform in Cambodia, 1975–1978

Journal of Political Ideologies ISSN: 1356-9317 (Print) 1469-9613 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cjpi20 Converts, not ideologues? The Khmer Rouge practice of thought reform in Cambodia, 1975–1978 Kosal Path & Angeliki Kanavou To cite this article: Kosal Path & Angeliki Kanavou (2015) Converts, not ideologues? The Khmer Rouge practice of thought reform in Cambodia, 1975–1978, Journal of Political Ideologies, 20:3, 304-332, DOI: 10.1080/13569317.2015.1075266 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2015.1075266 Published online: 25 Nov 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cjpi20 Download by: [24.229.103.45] Date: 26 November 2015, At: 10:12 Journal of Political Ideologies, 2015 Vol. 20, No. 3, 304–332, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2015.1075266 Converts, not ideologues? The Khmer Rouge practice of thought reform in Cambodia, 1975–1978 KOSAL PATH Brooklyn College, City University of New York, Brooklyn, NY 11210, USA ANGELIKI KANAVOU Interdisciplinary Center for the Scientific Study of Ethics & Morality, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697-5100, USA ABSTRACT While mistaken as zealot ideologues of Marxist ideals fused with Khmer rhetoric, the Khmer Rouge (KR) cadres’ collective profile better fits that of the convert subjected to intense thought reform. This research combines insights from the process and the context of thought reform informed by local cultural norms with the social type of the convert in a way that captures the KR phenome- non in both its general and particular dimensions. -

Justice for Genocide in Cambodia - the Case for the Prosecution

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 12 Issue 3 Justice and the Prevention of Genocide Article 7 12-2018 Justice for Genocide in Cambodia - The Case for the Prosecution William Smith Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation Smith, William (2018) "Justice for Genocide in Cambodia - The Case for the Prosecution," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 12: Iss. 3: 20-39. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.12.3.1658 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol12/iss3/7 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Justice for Genocide in Cambodia - The Case for the Prosecution Acknowledgements This address was prepared with the assistance of Caroline Delava, Martin Hardy and Andreana Paz, legal interns in the Office of the Co-Prosecutor. The opinions in this address are those of the author solely and reflect the concepts and essence of the address delivered at the Conference. This conference proceeding is available in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol12/iss3/7 Justice for Genocide in Cambodia - The Case for the Prosecution William Smith Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia Phnom Penh, Cambodia The Importance of Contemporaneous Documents and Academic Activism* Figure 1. -

Eine Filmische Annäherung an Die Verbrechen Der Roten Khmer

„Take the camera in your hands“ Eine filmische Annäherung an die Verbrechen der Roten Khmer Volker Grabowsky We Want [u] to Know. Remembering in the Time of the Khmer Rouge Trial. A Moving Journey Around Cambodia Using Film to Confront the Past, Film/DVD von Ella Pugliese und Nou Va mit Bewohnern von Kratie, Sonit Cum und Thnol Lok, Kambodscha 2009, 90 Min., Khmer mit englischen Untertiteln. Website: <http://www.we-want-u-to-know.com> Am 26. Juli 2010 verkündete das „Rote-Khmer-Tribunal“ in Phnom Penh1 ein Aufsehen erregendes Urteil: Kaing Guek Eav, der ehemalige Direktor von Tuol Sleng, des zentralen Gefängnisses der kambodschanischen Staatssicherheit, 1 Zur Entstehung des kambodschanischen Sondertribunals und zu den völkerrechtlichen Aspekten siehe Wolfgang Form, Justice 30 Years Later? The Cambodian Special Tribunal for the Punishment of Crimes against Humanity by the Khmer Rouge, in: Nationalities Papers 37 (2009), S. 889-923. Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History 8 (2011), S. 141-149 © Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen 2011 ISSN 1612–6033 142 Volker Grabowsky wurde wegen „Crimes Against Humanity“ zu einer Haftstrafe von 35 Jahren ver- urteilt. Diese Strafe wurde in Anrechnung der bislang verbüßten Untersu- chungshaft und wegen ursprünglich illegaler Inhaftierung auf 19 Jahre redu- ziert. Unter dem Eindruck heftiger Proteste von Seiten überlebender Opfer des Terrorregimes der Roten Khmer und ihrer Hinterbliebenen legte die Staatsanwaltschaft Mitte August Berufung gegen das Urteil ein. Sie forderte eine weitaus höhere Strafe, die angemessen die Schwere der Taten des inzwi- schen 67-jährigen Kaing Guek Eav – wegen seiner geringen Körpergröße auch Duch (Khmer: „der Kleine“) genannt – zu berücksichtigen habe. -

Rethinking Transitional Justice: Cambodia, Genocide, and a Victim-Centered Model Isabelle Chan Macalester College, [email protected]

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College International Studies Honors Projects International Studies Department 5-1-2006 Rethinking Transitional Justice: Cambodia, Genocide, and a Victim-Centered Model Isabelle Chan Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/intlstudies_honors Part of the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chan, Isabelle, "Rethinking Transitional Justice: Cambodia, Genocide, and a Victim-Centered Model" (2006). International Studies Honors Projects. Paper 3. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/intlstudies_honors/3 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the International Studies Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Studies Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter One The Phenomenon “Cambodia was a satellite of imperialism, of U.S. imperialism in particular…the poor peasants were the most impoverished, the most oppressed class in Cambodian society, and it was this class that was the foundation of the Cambodian Party … Revolution or people’s war in any country is the business of the masses and should be carried out primarily by their own efforts: there is no other way … the Kampuchean Revolution must have [the option of] two forms of struggle: peaceful mea ns; and means that are not peaceful. We will do our utmost to grasp firmly peaceful struggle … however, [we] must be ready at all times to adopt non-peaceful means of struggle if the imperialists and feudalists … stubbornly insist on forcing us to take th at road… in the past we held our destiny in our own hands, and then we allowed others to resolve it in our place.