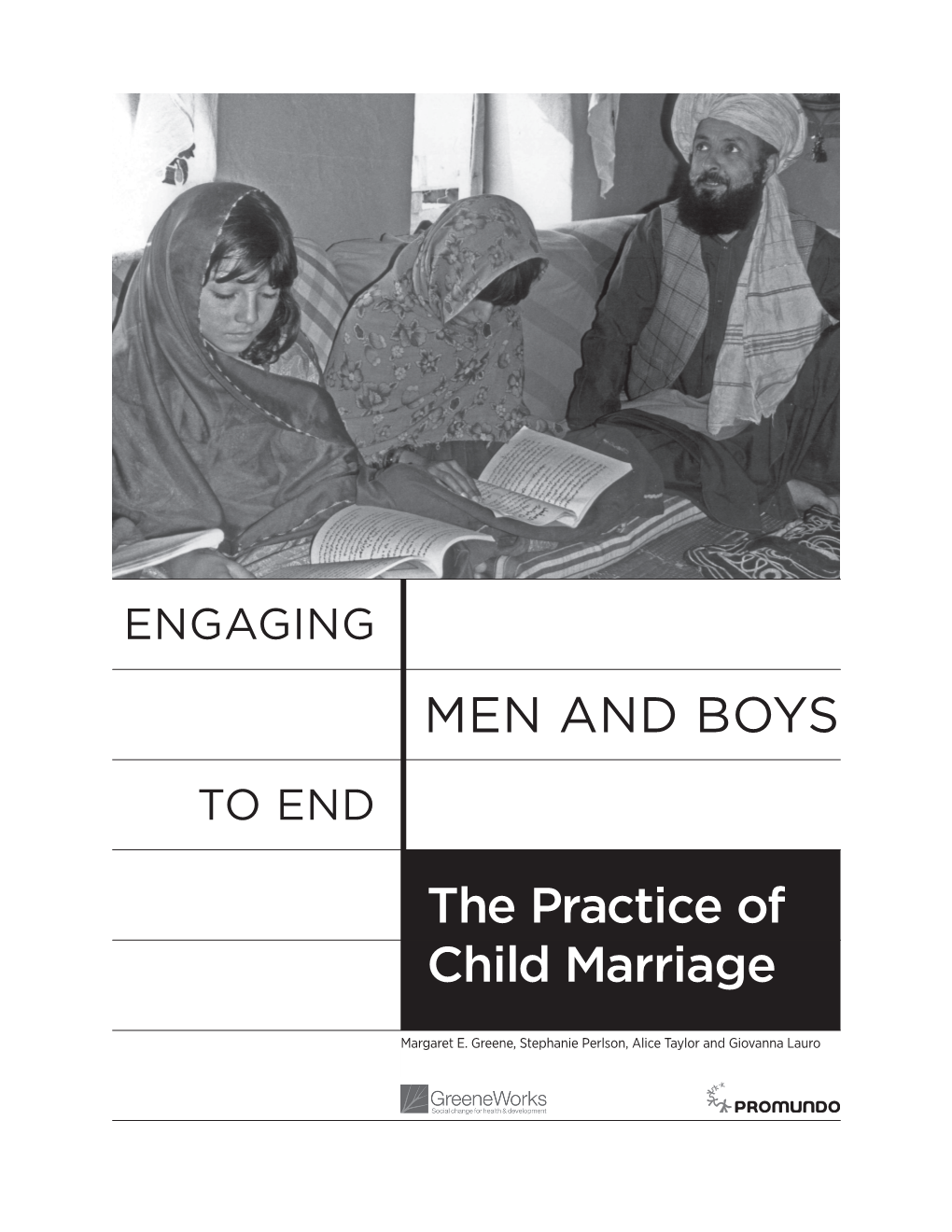

Engaging Men and Boys to End the Practice of Child Marriage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Married Too Young? the Behavioral Ecology of 'Child Marriage'

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Review Married Too Young? The Behavioral Ecology of ‘Child Marriage’ Susan B. Schaffnit 1,* and David W. Lawson 2 1 Department of Anthropology, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16801, USA 2 Department of Anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: For girls and women, marriage under 18 years is commonplace in many low-income nations today and was culturally widespread historically. Global health campaigns refer to marriage below this threshold as ‘child marriage’ and increasingly aim for its universal eradication, citing its apparent negative wellbeing consequences. Here, we outline and evaluate four alternative hypotheses for the persistence of early marriage, despite its associations with poor wellbeing, arising from the theoretical framework of human behavioral ecology. First, early marriage may be adaptive (e.g., it maximizes reproductive success), even if detrimental to wellbeing, when life expectancy is short. Second, parent– offspring conflict may explain early marriage, with parents profiting economically at the expense of their daughter’s best interests. Third, early marriage may be explained by intergenerational conflict, whereby girls marry young to emancipate themselves from continued labor within natal households. Finally, both daughters and parents from relatively disadvantaged backgrounds favor early marriage as a ‘best of a bad job strategy’ when it represents the best option given a lack of feasible alternatives. The explanatory power of each hypothesis is context-dependent, highlighting the complex drivers of life history transitions and reinforcing the need for context-specific policies Citation: Schaffnit, Susan B., and addressing the vulnerabilities of adolescence worldwide. -

Homeschooling and the Question of Socialization Revisited

Homeschooling and the Question of Socialization Revisited Richard G. Medlin Stetson University This article reviews recent research on homeschooled children’s socialization. The research indicates that homeschooling parents expect their children to respect and get along with people of diverse backgrounds, provide their children with a variety of social opportunities outside the family, and believe their children’s social skills are at least as good as those of other children. What homeschooled children think about their own social skills is less clear. Compared to children attending conventional schools, however, research suggest that they have higher quality friendships and better relationships with their parents and other adults. They are happy, optimistic, and satisfied with their lives. Their moral reasoning is at least as advanced as that of other children, and they may be more likely to act unselfishly. As adolescents, they have a strong sense of social responsibility and exhibit less emotional turmoil and problem behaviors than their peers. Those who go on to college are socially involved and open to new experiences. Adults who were homeschooled as children are civically engaged and functioning competently in every way measured so far. An alarmist view of homeschooling, therefore, is not supported by empirical research. It is suggested that future studies focus not on outcomes of socialization but on the process itself. Homeschooling, once considered a fringe movement, is now widely seen as “an acceptable alternative to conventional schooling” (Stevens, 2003, p. 90). This “normalization of homeschooling” (Stevens, 2003, p. 90) has prompted scholars to announce: “Homeschooling goes mainstream” (Gaither, 2009, p. 11) and “Homeschooling comes of age” (Lines, 2000, p. -

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

Kinship Terminology

Fox (Mesquakie) Kinship Terminology IVES GODDARD Smithsonian Institution A. Basic Terms (Conventional List) The Fox kinship system has drawn a fair amount of attention in the ethno graphic literature (Tax 1937; Michelson 1932, 1938; Callender 1962, 1978; Lounsbury 1964). The terminology that has been discussed consists of the basic terms listed in §A, with a few minor inconsistencies and errors in some cases. Basically these are the terms given by Callender (1962:113-121), who credits the terminology given by Tax (1937:247-254) as phonemicized by CF. Hockett. Callender's terms include, however, silent corrections of Tax from Michelson (1938) or fieldwork, or both. (The abbreviations are those used in Table l.)1 Consanguines Grandparents' Generation (1) nemesoha 'my grandfather' (GrFa) (2) no hkomesa 'my grandmother' (GrMo) Parents' Generation (3) nosa 'my father' (Fa) (4) nekya 'my mother' (Mo [if Ego's female parent]) (5) nesekwisa 'my father's sister' (Pat-Aunt) (6) nes'iseha 'my mother's brother' (Mat-Unc) (7) nekiha 'my mother's sister' (Mo [if not Ego's female parent]) 'Other abbreviations used are: AI = animate intransitive; AI + O = tran- sitivized AI; Ch = child; ex. = example; incl. = inclusive; m = male; obv. = obviative; pi. = plural; prox. = proximate; sg. = singular; TA = transitive ani mate; TI-0 = objectless transitive inanimate; voc. = vocative; w = female; Wi = wife. Some citations from unpublished editions of texts by Alfred Kiyana use abbreviations: B = Buffalo; O = Owl (for these, see Goddard 1990a:340). 244 FOX -

The Bat Boy & His Violin

Set 3 3–5 Guide for The Bat Boy & His Violin: What’s the Story? “Strike three, you’re out!” shouts the umpire. The Dukes are losing The Bat Boy again. They’re known as the worst team in the Negro National League, and the 1948 season is turning out to be their worst & His Violin by Gavin Curtis yet—at least until Reginald comes along. Reginald’s father, the Dukes’ manager, brings his son to the games because he needs a bat boy, but Reginald would much rather play the violin. Reginald’s father does not seem to appreciate or even understand his son’s musical ability. But when Reginald fills the ballpark with the stirring sounds of Mozart, Beethoven, and Bach, the Dukes start winning. Eventually they lose to the famous Monarchs, but win or lose, Reginald’s father develops a renewed pride in his son and his gift for music. ISBN 978-1-57621-249-3 2000 Embarcadero, Suite 305 Oakland, CA 94606-5300 y(7IB5H6*MLMOTN( +;!z!”!z!” 800.666.7270 * 510.533.0213 * fax: 510.464.3670 e-mail: [email protected] * www.devstu.org KL-G319 Illustrations by Todd Graveline Illustrations by Todd AfterSchool elcome to KidzLit® The purpose of this program is simple—to help you build a love of Funding for the Developmental Studies Center has been generously provided by: reading and strong relationships at your site. You don’t have to be a W trained teacher or a literature expert to be a successful AfterSchool The Annenberg Foundation, Inc. The MBK Foundation KidzLit leader. -

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy with At-Risk Families

ISSUE BRIEF January 2013 Parent-Child Interaction Therapy With At-Risk Families Parent-child interaction therapy (PCIT) is a family-centered What’s Inside: treatment approach proven effective for abused and at-risk children ages 2 to 8 and their caregivers—birth parents, • What makes PCIT unique? adoptive parents, or foster or kin caregivers. During PCIT, • Key components therapists coach parents while they interact with their • Effectiveness of PCIT children, teaching caregivers strategies that will promote • Implementation in a child positive behaviors in children who have disruptive or welfare setting externalizing behavior problems. Research has shown that, as a result of PCIT, parents learn more effective parenting • Resources for further information techniques, the behavior problems of children decrease, and the quality of the parent-child relationship improves. Child Welfare Information Gateway Children’s Bureau/ACYF 1250 Maryland Avenue, SW Eighth Floor Washington, DC 20024 800.394.3366 Email: [email protected] Use your smartphone to https:\\www.childwelfare.gov access this issue brief online. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy With At-Risk Families https://www.childwelfare.gov This issue brief is intended to build a better of the model, which have been experienced understanding of the characteristics and by families along the child welfare continuum, benefits of PCIT. It was written primarily to such as at-risk families and those with help child welfare caseworkers and other confirmed reports of maltreatment or neglect, professionals who work with at-risk families are described below. make more informed decisions about when to refer parents and caregivers, along with their children, to PCIT programs. -

South Africa

South Africa ~School Classes In South Africa, students generally take six to nine subjects at a time, and each class meets either every day or for extended sessions every other day. In South Africa, stu- dents are evaluated on daily homework, class participation, and periodic written exams. Boys and girls study in the same classes and are not seated apart in class. Th e class sizes vary depending on the school or subject. COUNTRY FACTS: School Relationships School is very formal and students are always expected to address school staff by the Capital: Pretoria surnames with the prefi x Mr. or Mrs. Population: 49,109,107 Extracurricular Activities Area, sq. mi.: 470,693 South African high school students are oft en very involved in school based extracur- ricular activities, and these activities are where most students develop their friendships. Real GDP per capita: 10,300 South Africans have freedom to participate in which ever extracurricular activities that Adult literacy rate: 87% (male); they like. 86% (female) Ethnic make-up: black African School Rules South African high schools have a “zero tolerance” policy regarding cell phone usage 79%, white 9.6%, colored 8.9%, and fi ghting. Th ese activities are not allowed at all in school and the penalties for en- Indian/Asian 2.5% gaging in them are oft en severe and in some cases will include expulsion. Religion: Zion Christian 11.1%, Pentecostal/Charismatic 8.2%, Family Life In South Africa, most households consist of parents, or a parent, and their children. Catholic 7.1%, Methodist 6.8%, Rarely do grandparents, aunts, uncles or cousins live in the same house, but extended Dutch Reformed 6.7%, Anglican relatives may come to stay if the fi nancial situation requires it. -

Attitudes Toward Honor and Violence Against Women for Honor in the Context of the Concept of Privacy: a Study of Students in the Faculty of Health Sciences

Connectist: Istanbul University Journal of Communication Sciences, 2018, 54: 65-84 DOI: 10.26650/CONNECTIST433995 Connectist: Istanbul University Journal of Communication Sciences E-ISSN: 2636-8943 Araştırma Makalesi / Research Article Attitudes toward Honor and Violence against Women for Honor in the Context of the Concept of Privacy: A Study of Students in the Faculty of Health Sciences Nurten KAYA1 , Nuray TURAN2 ABSTRACT The study was conducted to examine the attitudes of students of health sciences towards violence against women for honor within the context of the concept of privacy and to determine how the attitudes of midwifery students towards honor differ from those of other students. The research design chosen for this study is 1Prof. Dr., Istanbul University, Health Sciences that of a survey. The subjects of the research consisted of students of health Faculty, Istanbul, Turkey sciences (N=952), and the sample amounted to 473 students who were selected 2PhD Lecturer, Istanbul University, Florence Nightingale Nursing Faculty, Istanbul, Turkey from this population by stratified random sampling method (departments and classes were taken as stratum criterion). A Student Information Form, the Attitudes towards Honor Scale (AHS), and the Attitudes towards Violence against Women for Sorumlu yazar/Corresponding author: Protecting Honor Scale (AVWPHS) were used in the data collection. By considering Nuray Turan, İstanbul Üniversitesi, Florence Nightingale that gender is an important confounding factor in attitudes towards honor, data Hemşirelik Fakültesi, İstanbul, Türkiye were presented by dividing subjects into three groups: an all-female group from E-posta/E-mail: [email protected] the midwifery department (MS, n=97), female students in other departments (FSOD, n=227), and male students in other departments (MSOD, n=148). -

Report on Exploratory Study Into Honor Violence Measurement Methods

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Report on Exploratory Study into Honor Violence Measurement Methods Author(s): Cynthia Helba, Ph.D., Matthew Bernstein, Mariel Leonard, Erin Bauer Document No.: 248879 Date Received: May 2015 Award Number: N/A This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this federally funded grant report available electronically. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Report on Exploratory Study into Honor Violence Measurement Methods Authors Cynthia Helba, Ph.D. Matthew Bernstein Mariel Leonard Erin Bauer November 26, 2014 U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics Prepared by: 810 Seventh Street, NW Westat Washington, DC 20531 An Employee-Owned Research Corporation® 1600 Research Boulevard Rockville, Maryland 20850-3129 (301) 251-1500 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Table of Contents Chapter Page 1 Introduction and Overview ............................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Summary of Findings ........................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Defining Honor Violence .................................................................... 1-2 1.3 Demographics of Honor Violence Victims ...................................... 1-5 1.4 Future of Honor Violence ................................................................... 1-6 2 Review of the Literature ................................................................................... -

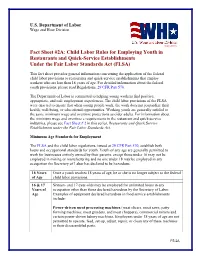

Child Labor Rules for Employing Youth in Restaurants and Quick-Service Establishments Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division (July 2010) Fact Sheet #2A: Child Labor Rules for Employing Youth in Restaurants and Quick-Service Establishments Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) This fact sheet provides general information concerning the application of the federal child labor provisions to restaurants and quick-service establishments that employ workers who are less than 18 years of age. For detailed information about the federal youth provisions, please read Regulations, 29 CFR Part 570. The Department of Labor is committed to helping young workers find positive, appropriate, and safe employment experiences. The child labor provisions of the FLSA were enacted to ensure that when young people work, the work does not jeopardize their health, well-being, or educational opportunities. Working youth are generally entitled to the same minimum wage and overtime protections as older adults. For information about the minimum wage and overtime e requirements in the restaurant and quick-service industries, please see Fact Sheet # 2 in this series, Restaurants and Quick Service Establishment under the Fair Labor Standards Act. Minimum Age Standards for Employment The FLSA and the child labor regulations, issued at 29 CFR Part 570, establish both hours and occupational standards for youth. Youth of any age are generally permitted to work for businesses entirely owned by their parents, except those under 16 may not be employed in mining or manufacturing and no one under 18 may be employed in any occupation the Secretary of Labor has declared to be hazardous. 18 Years Once a youth reaches 18 years of age, he or she is no longer subject to the federal of Age child labor provisions. -

Running Head: PROTOTYPES and DIMENSIONS of HONOR

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Kent Academic Repository Running Head: PROTOTYPES AND DIMENSIONS OF HONOR Cultural Prototypes and Dimensions of Honor Susan E. Cross1 Ayse K. Uskul2 ([email protected]) Berna Gerçek-Swing1([email protected]) Zeynep Sunbay3 ([email protected]) Cansu Alözkan3 ([email protected]) Ceren Günsoy1 ([email protected]) Bilge Ataca4 ([email protected]) Zahide Karakitapoğlu-Aygün5 ([email protected]) 1Iowa State University, USA, 2University of Kent, UK, 3Istanbul Bilgi University, Turkey, 4Boğaziçi University, Turkey, 5Bilkent University, Turkey In press, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin; DOI: 10.1177/0146167213510323 Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Susan E. Cross, Department of Psychology, W112 Lagomarcino Hall, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa 50011, USA. Email: [email protected]. Prototypes and Dimensions of Honor 2 Abstract Research evidence and theoretical accounts of honor point to differing definitions of the construct in differing cultural contexts. The current studies address the question “What is honor?” using a prototype approach in Turkey and the northern US. Studies 1a/1b revealed substantial differences in the specific features generated by members of the two groups, but Studies 2 and 3 revealed cultural similarities in the underlying dimensions of Self-Respect, Moral Behavior, and Social Status/Respect. Ratings of the centrality and personal importance of these factors were similar across the two groups, but their association with other relevant constructs differed. The tri-partite nature of honor uncovered in these studies helps observers and researchers alike understand how diverse responses to situations can be attributed to honor. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Alternative Coming-Of-Age Motion Picture

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 Screening Male Crisis: A Comparative Analysis of the Alternative Coming-of-Age Motion Picture Matthew J. Tesoro The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1447 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Screening Male Crisis: A Comparative Analysis of the Alternative Coming-of-Age Motion Picture By Matthew Tesoro A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 MATTHEW TESORO All Rights Reserved ii Screening Male Crisis: A Comparative Analysis of the Alternative Coming-of-Age Motion Picture By Matthew Tesoro This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts ____________ ________________________ Date Robert Singer Thesis Advisor ____________ ________________________ Date Matthew Gold MALS Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Screening Male Crisis: A Comparative Analysis of the Alternative Coming-of- Age Motion Picture By Matthew Tesoro Advisor: Robert Singer This thesis will identify how the principle male character in select film narratives transforms from childhood through his adolescence in multiple locations and historical eras.