Draft Copy: Please Do Not Cite Or Circulate 1 Agrarian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Anandgram Paud” by M/S Vastushodh Realty at Gat No.. 263 (P), 273(P), 275, 276 (P), 283 at Paud, Taluka Mulshi, District – Pune

Form 1 & 1A for Proposed Project “AnandGram Paud” by M/S Vastushodh Realty at Gat No.. 263 (P), 273(P), 275, 276 (P), 283 At Paud, Taluka Mulshi, District – Pune APPENDIX II (See paragraph 6) FORM-1 A (only for construction projects listed under item 8 of the Schedule) CHECK LIST OF ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS 1. LAND ENVIRONMENT (Attach panoramic view of the project site and the vicinity) 1.1. Will the existing land use get significantly altered from the project that is not consistent with the surroundings? (Proposed land use must conform to the approved Master Plan / Development Plan of the area. Change of land use if any and the statutory approval from the competent authority be submitted). Attach Maps of (i) site location, (ii) surrounding features of the proposed site (within 500 meters) and (iii) the site (indicating levels & contours) to appropriate scales. If not available attach only conceptual plans. The proposed land use is in conformity with the Development Plan (DP) of the area. REFER ANNEXURE I: AERIAL VIEW REFER ANNEXURE II: SITE LOCATION PLAN & DP PLAN REFER ANNEXURE III: CONTOUR LEVELS PLAN REFER ANNEXURE IV: MASTER LAYOUT PLAN REFER ANNEXURE VI: PARKING & TRAFFIC MANAGEMENT PLAN 1.2. List out all the major project requirements in terms of the land area, built up area, water consumption, power requirement, connectivity, community facilities, parking needs etc. Details are as follows: Total Plot Area: 42850.00 m2 Total Built up Area (FSI): 28790.63 m2 Total Built up Area (NON FSI): 13235.10 m2 Total Construction Area: 42025.73 m2 Form 1 & 1A for Proposed Project “AnandGram Paud” by M/S Vastushodh Realty at Gat No. -

19 Feb 2018 165612747QRIW

POINT WISE COMPLIANCE REPORT (Query’s raised during EC presentation – 26th meeting of EAC on 14th December 2017) For Proposed Expansion of IT Park, Infosys Limited at Plot No 24, MIDC, Rajiv Gandhi InfoTech Park Phase II, Village- Mann, Tal-Mulshi, Hinjawadi, Pune (MH)-411057 Project Proponent Environment Consultant QCI-NABET & ISO 9001:2008, ISO 14001:2004, OHSAS 18001:2007 Accredited EIA Consultant, MoEF & CC (GOI) and NABL recognized Laboratory 60, Bajiprabhu Nagar, Nagpur - 440 033, MS Lab. : FP-34, 35, Food Park, MIDC, Butibori, Nagpur – 441122 Ph. : (0712) 2242077, 9373287475 Fax: (0712) 2242077 Email: [email protected] website: www.anaconlaboratories.com FEBRUARY, 2018 The points raised by Honorable Expert Appraisal Committee during presentation for Environmental Clearance in 26th meeting of Expert Appraisal Committee (Infra-2) on 14th December, 2017, Item No. 26.3.13 S.No. Points Raised By Hon’ble SEIAA Proponent’s compliance / Reply i. Submit copy of revised Form-1/1-A Copy of Form 1 & Form 1A revised for Area stating the complete details of Area Statement and other particulars as per EIA Report Statement is attached as Annexure 1. ii. An action taken report on Response to the actions taken on non- environmental conditions stated to be complied/partly complied EC conditions as not complied/partly complied as reported in Certified Compliance Report letter F. reported in Certified Compliance No. 18-C-51/2011/SEAC/dated 27.09.2017 is Report letter F. No. 18-C- submitted to the MoEF&CC’s Regional Office 51/2011/SEAC/dated 27.09.2017 (WCZ), Nagpur on 14th December 2017. -

By Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Vidyavachaspati (Doctor of Philosophy) Faculty for Moral and Social Sciences Department Of

“A STUDY OF AN ECOLOGICAL PATHOLOGICAL AND BIO-CHEMICAL IMPACT OF URBANISATION AND INDUSTRIALISATION ON WATER POLLUTION OF BHIMA RIVER AND ITS TRIBUTARIES PUNE DISTRICTS, MAHARASHTRA, INDIA” BY Dr. PRATAPRAO RAMGHANDRA DIGHAVKAR, I. P. S. THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF VIDYAVACHASPATI (DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY) FACULTY FOR MORAL AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDHYAPEETH PUNE JUNE 2016 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the entire work embodied in this thesis entitled A STUDY OFECOLOGICAL PATHOLOGICAL AND BIOCHEMICAL IMPACT OF URBANISATION AND INDUSTRILISATION ON WATER POLLUTION OF BHIMA RIVER AND Its TRIBUTARIES .PUNE DISTRICT FOR A PERIOD 2013-2015 has been carried out by the candidate DR.PRATAPRAO RAMCHANDRA DIGHAVKAR. I. P. S. under my supervision/guidance in Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. Such materials as has been obtained by other sources and has been duly acknowledged in the thesis have not been submitted to any degree or diploma of any University or Institution previously. Date: / / 2016 Place: Pune. Dr.Prataprao Ramchatra Dighavkar, I.P.S. DECLARATION I hereby declare that this dissertation entitled A STUDY OF AN ECOLOGICAL PATHOLOGICAL AND BIO-CHEMICAL IMPACT OF URBANISNTION AND INDUSTRIALISATION ON WATER POLLUTION OF BHIMA RIVER AND Its TRIBUTARIES ,PUNE DISTRICT FOR A PERIOD 2013—2015 is written and submitted by me at the Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The present research work is of original nature and the conclusions are base on the data collected by me. To the best of my knowledge this piece of work has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any University or Institution. -

Prospective Wild Edible Fruit Plants from Part of Northern Western Ghats

Journal of Medicinal Plants Studies 2016; 4(1): 15-19 ISSN 2320-3862 JMPS 2016; 4(1): 15-19 Prospective wild edible fruit plants from part of © 2016 JMPS Received: 13-11-2015 northern Western Ghats (NWG), Mulshi (MS), Accepted: 14-12-2015 India Rani B Bhagat Department of Botany, Anantrao Pawar College, Rani B Bhagat, Mahadev Chambhare, Sandip Mate, Amit Dudhale, Pirangut, Pune- 412115, BN Zaware Maharashtra, India Mahadev Chambhare Abstract Department of Botany, A survey was carried out to document traditional religious information of prospective wild edible fruits Anantrao Pawar College, consumed by tribal and non tribal communities in Mulshi, a part of Northern Western Ghats (NWG). Pirangut, Pune- 412115, Forests represent an integral part of the social life of tribal groups and are home to the people who are Maharashtra, India completely or partly dependent on forests for their livelihood. The communities in Mulshi include “Marathas”, "Katkari" "Mahadeo koli" and “Dhangars”. The study area is rich in genetic and species Sandip Mate diversity including rare, endemic, endangered and threatened (RET) category species. The wild edible Department of Botany, fruits plays fundamental role in human diet and are enriched with macronutrients, microelements, Anantrao Pawar College, secondary metabolites and have high nutritional value. The fruits are eaten either as a raw in ripe or Pirangut, Pune- 412115, unripe condition. The total of 109 wild edible fruit plant species belonging to 85 genera and 57 families Maharashtra, India has been investigated in present research work. The potentialities of these fruits could be explored and utilized for pharmaceutical industry or as an additional fruit crop source in agriculture with high food Amit Dudhale value and with exceptional medicinal properties. -

Bpc(Maharashtra) (Times of India).Xlsx

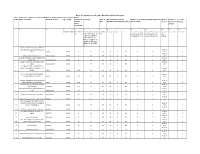

Notice for appointment of Regular / Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships BPCL proposes to appoint Retail Outlet dealers in Maharashtra as per following details : Sl. No Name of location Revenue District Type of RO Estimated Category Type of Minimum Dimension (in Finance to be arranged by the applicant Mode of Fixed Fee / Security monthly Site* M.)/Area of the site (in Sq. M.). * (Rs in Lakhs) Selection Minimum Bid Deposit Sales amount Potential # 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 Regular / Rural MS+HSD in SC/ SC CC1/ SC CC- CC/DC/C Frontage Depth Area Estimated working Estimated fund required Draw of Rs in Lakhs Rs in Lakhs Kls 2/ SC PH/ ST/ ST CC- FS capital requirement for development of Lots / 1/ ST CC-2/ ST PH/ for operation of RO infrastructure at RO Bidding OBC/ OBC CC-1/ OBC CC-2/ OBC PH/ OPEN/ OPEN CC-1/ OPEN CC-2/ OPEN PH From Aastha Hospital to Jalna APMC on New Mondha road, within Municipal Draw of 1 Limits JALNA RURAL 33 ST CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 Draw of 2 VIllage jamgaon taluka parner AHMEDNAGAR RURAL 25 ST CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 VILLAGE KOMBHALI,TALUKA KARJAT(NOT Draw of 3 ON NH/SH) AHMEDNAGAR RURAL 25 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 Village Ambhai, Tal - Sillod Other than Draw of 4 NH/SH AURANGABAD RURAL 25 ST CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 ON MAHALUNGE - NANDE ROAD, MAHALUNGE GRAM PANCHYAT, TAL: Draw of 5 MULSHI PUNE RURAL 300 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 ON 1.1 NEW DP ROAD (30 M WIDE), Draw of 6 VILLAGE: DEHU, TAL: HAVELI PUNE RURAL 140 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 VILLAGE- RAJEGAON, TALUKA: DAUND Draw of 7 ON BHIGWAN-MALTHAN -

EIA: India: Pune Nirvana Hills Slum Rehabilitation Project

Environment and Social Impact Assessment Report and Environment and Social Management Plan Project Number: 44940 March 2012 IND: Pune Nirvana Hills Slum Rehabilitation Project Prepared by: Kumar Urban Development Limited This report is made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s Public Communications Policy (2005). It does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB. Environmental and Social Impact Assessment for Project Nirvana: Pune, India Kumar Sinew Developers Private Final Report Limited March 2012 www.erm.com Delivering sustainable solutions in a more competitive world FINAL REPORT Kumar Sinew Developers Private Limited Environmental and Social Impact Assessment for Project Nirvana: Pune, India 23 March 2012 Reference : I8390 / 0138632 Rutuja Tendolkar Prepared by: Consultant Reviewed & Neena Singh Approved by: Partner This report has been prepared by ERM India Private Limited, with all reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of the Contract with the client, incorporating our General Terms and Conditions of Business and taking account of the resources devoted to it by agreement with the client. We disclaim any responsibility to the client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of the above. This report is confidential to the client and we accept no responsibility of whatsoever nature to third parties to whom this report, or any part thereof, is made known. Any such party relies on the report at their own risk. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ERM India Private Limited has been engaged by M/s Kumar Sinew Urban Developers Limited (hereinafter referred to as ‘KUL’ or ‘the client’) on the behest of the Asian Development Bank (ADB), to update the Environmental Impact Assessment report of the “Nirvana Hills Phase II” Project (hereinafter referred to as ‘Project Nirvana’) located at Survey No. -

Management of Livelihood: Study of Selected Villages in Mulshi Tahsil in Maharashtra State

International Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & Management (IJAIEM) Web Site: www.ijaiem.org Email: [email protected], [email protected] ISSN 2319 - 4847 Special Issue for National Conference On Recent Advances in Technology and Management for Integrated Growth 2013 (RATMIG 2013) Management of Livelihood: Study of Selected Villages in Mulshi Tahsil in Maharashtra State. Amar M Dhere1, G.M.Pondhe2, Janradan A Pawar3 1Faculty, Environmental Science, Indira College of Commerce and Science, Pune, 411033, [email protected] Head P.G. Deptt. of Environmental Science, 2PVP College of Arts, Commerce and Science, Pravaranagar-Loni Dist. Ahemadnagar. 3Vice-Principal, Indira College of Commerce and Science, Pune 411033. ABSTRACT This research article aims to find the management of livelihood with the selected case study of Mulshi tahsil in Pune district. There are four villages selected through the purposive sampling method. However, information related to livelihood is collected from the 400 respondents which are selected through the accidental sampling method. Livelihood of the respective villages are purely depends on the agricultural activities. Although these villages are not so far from the Pune City but the development was very poor. The Japanese Cooperation support these villagers to earn the money from milk and allied agriculture activities but their benefits are limited to some class. Education, medical and economic filed in the selected villages are lagging behind the development of villagers. Therefore this study suggests that, there may be urgent attention for proper management of livelihood activities to give them opportunities to develop. Key Words- livelihood , agriculture, village, management. 1. Introduction Livelihood means of supporting one's existence, especially financially or vocationally; living: to earn a livelihood as a tenant farmer. -

Study of Water Quality Parameters of Mula-Mutha River at Pune, Maharashtra (India)

International Journal of Lakes and Rivers. ISSN 0973-4570 Volume 13, Number 1 (2020), pp. 95-103 © Research India Publications http://www.ripublication.com/ijlr.htm Study of Water Quality Parameters of Mula-Mutha River at Pune, Maharashtra (India) S.D. Jadhav1, M.S. Jadhav2 1Department of Basic Sciences & Humanities, Bharati Vidyapeeth (Deemed To Be University), College of Engineering, Pune 411043, Maharashtra, India., 2 Department of Civil Engineering, Sinhgad Technical Education Society’s Sou., Venutai Chavan Polytechnic, Pune, Maharashtra, India. Abstract Water is one of the most important compounds in the world. The contamination and pollution of water is of great concern in the world for the developing countries like India. The question of water pollution has acquired a critical stage. Human activities, industries, hospitals, sewage water, agricultural diffused pollution are some of the sources of water pollution. Drinking water quality is one of the important environmental health detriments. Use of safe drinking water is a foundation for the control and prevention of water born diseases. In this work we have analyzed Mula-Mutha river water quality for drinking purpose. Various river water parameters were analyzed and are compared to established standards given by WHO. The river water analysis showed that the river water is not suitable for potable use in city area. Keywords: Mula-Mutha River, Pune City, Physico-chemical analysis, Water pollution INTRODUCTION The entire Pune City is covered by Mula-Mutha rivers. River Mula originates from Mulshi Dam which forms Mulshi Lake. River Mutha originates from Panshet Dam Via Khadakwasla Dam. It also flows through city of Pune and meets to river Mula at Shivajinagar area of Pune city, to that part it called as Sangam Bridge. -

Organizational Set up of CBEC

Organizational Set Up of CBEC Updated as on 19.02.2015 [Training Material for departmental use] E-BOOK On Organizational Set Up of CBEC After Cadre Restructuring Prepared by NACEN, RTI, Kanpur Page 0 Organizational Set Up of CBEC Note: In this E-book, attempts have been made to know about Organizational Set up of CBEC after Cadre Restructuring. It is expected that it will help the new entrants into the service. Though all efforts have been made to make this document error free, but it is possible that some errors might have crept into the document. If you notice any errors or if you have any suggestion to improve this document, the same may be brought to the notice to the NACEN, RTI, Kanpur on the Email addresses: [email protected] or [email protected] (Email address of ADG, RTI, NACEN, Kanpur). This may not be a prefect E-book and all are requested to assist us to make it better. Prepared by NACEN, RTI, Kanpur Page 1 Organizational Set Up of CBEC INDEX Organization & Functions .................................................................................................................. 3 Composition and Functions of Central Board of Excise and Customs .............................................. 3 Attached Offices of CBEC................................................................................................................. 3 Structure of Field Formations under CBEC....................................................................................... 4 Territorial Jurisdiction of Central Excise Commissionerates -

In Exercise of the Powers Conferred by Rule 3 of the Central Excise Rules , 2002 and in Supersession of Ministry of Finance (Department of Revenue) Notification No

[ TO BE PUBLISHED IN THE GAZETTE OF INDIA , EXTRAORDINARY , PART II , SECTION 3 , SUB-SECTION (i) ] Government of India Ministry of Finance (Department of Revenue ) Notification No. 27 / 2014 – Central Excise (N.T.) New Delhi the 16th September, 2014 G.S.R.(E)….. In exercise of the powers conferred by rule 3 of the Central Excise Rules , 2002 and in supersession of Ministry of Finance (Department of Revenue) notification No. 14/2002- Central Excise (N.T.), dated the 8th March, 2002 , published vide number G.S.R.182(E), dated the 8th March , 2002 , except as respects things done or omitted to be done before such supersession , the Central Board of Excise and Customs hereby specifies in the Tables below , the jurisdiction of the Principal Chief Commissioners of Central Excise as specified in column (3) of the Tables I(A) and I(B) , the jurisdiction of the Chief Commissioners of Central Excise as specified in column (3) of the Tables II(A) and II(B) , the jurisdiction of the Principal Commissioners of Central Excise as specified in column (3) of Table III(A) , the jurisdiction of the Commissioners of Central Excise as specified in column (3) of Table III(B) , the jurisdiction of Commissioners of Central Excise (Appeal) or the Commissioners of Central Excise ( Audit ) as specified in column (3) of Table IV and appoints the officers specified in columns (2) and (3) of Table V and the subordinate officers posted under them as Central Excise Officers having jurisdiction over the Central Excise assessees registered in the territorial jurisdiction of the Principal Commissioners or the Commissioners of Central Excise, as the case may be, specified in column (4) of the said Table, for the purposes of the Central Excise Act, 1944 (1 of 1944) and the rules made there under , namely :- Table-I(A) S.No. -

S.No. Commissioner of Central Excise Jurisdiction

The Districts of Panchmahal and Dahod, and the following areas of District of Vadodara :- (a) Waghodia Taluka, (b) Area of Karjan Taluka and Vadodara Taluka bound by Vadodara-Mumbai railway line on the west, on the east by the boundaries of Karjan Taluka and 23 Vadodara Taluka, on the north by Jambuva river, on the south by the Vadodara-II boundary of Vadodara District, and (c) Area of Vadodara Taluka bound on the west by Mumbai-Vadodara railway line, on the north by GIDC (Gujarat Industrial Development Corporation) Ring Road from Vadsar overbridge to Sussen crossroads, on the south by Jambuva river, and on the east by old National Highway No.8. In the Districts of Srikakulam, Vizianagaram and Visakhapatnam excluding the mandals of Nakkapalli, Sarvasidhi Rayavaram, Yelamanchili, Rambilli, Kasimkota, Atchutapuram, Paravada, Anakapalli, Chodavaram, Cheedikada, Hukumpeta, Butchayyapeta, Kotauratla, Makavarapalem, Ravikamatham, Madugula, Paderu, Visakhapatnam Pedabayalu, Munchingiputtu, Gangaraju Madugula, Chintapalle, 24 ( Visakhapatnam-I) Gudem Kothaveedhi, Payakaraopeta, Koyyuru, Roluguntla, Narsipatnam, Nathavaram, Pedagantyada, Munagapaka, Sabbavaram, Golugunta and Gajuwaka mandal but including the villages/ Areas of Thunglam and the entire area falling under Autonagar Industrial Area, Akkareddipalem, Mindi, Nathayyapalem, Dolphin’s Nose and Yarada of Gajuwaka mandal in the State of Andhra Pradesh. 25 Large Taxpayer Unit Throughout the territory of India TableIII(B) S.No. Commissioner of Jurisdiction Central Excise (1) (2) (3) Districts of Agra, Ferozabad, Hathras, Mathura, Aligarh, Auraiya, 1 Agra Etawah, Farrukhabad, Kannauj, Mainpuri, Etah and Kasganj of the State of Uttar Pradesh . Area on the eastern side of Sabarmati river starting from Nehru Bridge towards northern side of Relief Road extending upto Kalupur. -

(ICA) the INSTITUTE of CULTURAL AFFAIRS: INDIA Activity Report of Year 2015-16

(ICA) THE INSTITUTE OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS: INDIA Activity report of year 2015-16 COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT- Khamboli Human Development Project, Mulshi taluka continue its work on their own with very invisible support of ICA India. The work is in 4 villages- Khamboli, Katarkhadak, Kemsewadi & Andhale. Lift Irrigation scheme in Katarkhadak is run by farmers cooperative. Farmers are taking second crop and their income is increased, and helping families economically. Women’s Self Help Group monthly meetings held to see on going activities, plan monthly activity plan and discuss any problems they have. The restaurant in Khamboli run by women is doing well, women are selling extra products like snacks and Sarees to women. Few women make some other products such as Masala, sweet chapatti, sell eggs, hand pounded rice, flavored papad etc. Women continue monthly fund collection individually and uses for lending it to needy women in the village. Government Agriculture department conducted a meeting with women and farmers for providing them information of agriculture support and crop information. A tailoring class of 3 months for 12 girls from village held in Khamboli village, teaching them women’s clothes stitching. Tailoring machines given to women for practicing at their home. Education study tour from Japan visited project, saw the activities and discussed with beneficiaries of their work and success stories. Funding agency JICA, Japan International cooperation agency team visited project to see the progress of development activities and found that the Lift Irrigation Scheme in Katarkhadak is running successfully by farmers cooperative and provided great economical support to families by taking agriculture crops, such as wheat, vegetables, potato, ground nuts etc.