Between Two Time Zones and Places

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Årsrapport Innholdsoversikt / NRK 2007

07 Årsrapport INNHOLDSOVERSIKT / NRK 2007 FORORD 3 DRAMA 32 KANALER 62 Om fjernsynsdrama 33 NRK1 63 NYHETER 4 Berlinerpoplene 33 NRK2 64 Ny design og innholdsprofil 5 Utradisjonell seing 34 NRK3 64 Nye NRK2 5 Kodenavn hunter 35 NRK Super 64 Bred valgdekning 6 Størst av alt 36 NRK P1 65 Nyheter på nrk.no 6 Radioteateret 36 NRK P2 66 Nyheter på P1 8 NRK P3 66 Nyheter på P2 8 FAKTA & VITENSKAP 38 Andre kanaler 67 Osenbanden på P3 8 Faktajournalistikk i NRK 39 NRK Sport 67 Internasjonale nyheter 9 Spekter 39 NRK Jazz 67 SKUP-pris til Dagsrevyen 9 Puls — i tre kanaler 40 NRK Båtvær 67 Egenproduksjon 9 Jordmødre 40 NRK Gull 67 yr.no 41 NRK Super 67 BARN 10 Ekstremværuka 42 NRK 5.1 68 Super på tv 11 Radiodokumentaren 43 Alltid Klassisk 68 Superbarn 11 Alltid Nyheter 68 Superstore 12 MINORITETER 44 Alltid Folkemusikk 68 Super på radio 13 10 års jubilant på tv 45 NRK mP3 68 Super på nett 13 Dokumentarer om det flerkulturelle 45 P3 Urørt 68 Spiller.no 13 Norge NRK P1 Oslofjord 68 Melodi Grand Prix Jr 14 Bollywoodsommer 46 NRK Sámi Radio 69 Dokumentar og drama for 14 Kvener 46 NRK1 Tegnspråk 69 barn og unge Musikk 46 NRK Stortinget 69 Ettermiddagstilbud for unge 14 Språklig og kulturelt mangfold i NRK 47 NRK som podkast 69 Nrk.no 69 SPORT 15 LIVSSYN 48 Språkarbeid og nynorskbruk i NRK 70 Vinteridrett 16 Livssyn i faste programmer 49 Teksting av programmer 70 Sportsnyheter 16 Det skjedde i de dager 49 Sportsportalen 16 Salmer til alle tider 49 Ung sport 17 Morgenandakten på P1 49 Fotball på fjernsyn og radio 17 Mellom Himmel og jord 49 Bakrommet -

The World on Television Market-Driven, Public Service News

10.1515/nor-2017-0128 Nordicom Review 31 (2010) 2, pp. 31-45 The World on Television Market-driven, Public Service News Øyvind Ihlen, Sigurd Allern, Kjersti Thorbjørnsrud, & Ragnar Waldahl Abstract How does television cover foreign news? What is covered and how? The present article reports on a comparative study of a license-financed public broadcaster and an advertising- financed channel in Norway – the NRK and TV2, respectively. Both channels give priority to international news. While the NRK devotes more time to foreign news (both in absolute and relative numbers) than TV2 does, other aspects of the coverage are strikingly similar: The news is event oriented, there is heavy use of eyewitness footage, and certain regions are hardly visible. At least three explanations can be used to understand these findings: the technological platform (what footage is available, etc.) and the existence of a common news culture that is based on ratings and similar views on what is considered “good television”. A third factor is that both channels still have public service obligations. Keywords: foreign news, television news, public service Introduction The media direct attention toward events and occurrences in the world, and help to shape our thinking as well as our understanding of these events. The potentially greatest influ- ence can be expected to occur with regard to matters of which we have little or no direct experience. Foreign news is a prime example of an area where most of us are reliant on what the media report. Studies of foreign news have a long tradition (i.e., Galtung & Ruge 1965) and there is a vast body of literature focusing on the criteria for what becomes news (e.g., Harcup & O’Neill 2001; Hjarvard 1995, 1999; Shoemaker & Cohen 2006). -

Endgame in Sri Lanka Ajit Kumar Singh*

Endgame in Sri Lanka Ajit Kumar Singh* If we do not end war – war will end us. Everybody says that, millions of people believe it, and nobody does anything. – H.G. Wells 1 The Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapakse finally ended the Eelam War2 in May 2009 – though, perhaps, not in the manner many would desire. So determined was the President that he had told Roland Buerk of the BBC in an interview published on February 21, 2007, “I don't want to pass this problem on to the next generation.”3 Though the final phase of open war4 began on January 16, 2008, following the January 2 unilateral withdrawal of the Government of Sri Lanka (GoSL) from the Norway-brokered * Ajit Kumar Singh, Research Fellow, Institute for Conflict Management 1 Things to Come (The film story), Part III, adapted from his 1933 novel The Shape of Things to Come, spoken by the character John Cabal. 2 The civil war in Sri Lanka can be divided into four phases: Eelam War I between 1983 and 1987, Eelam War II between 1990-1994, Eelam War III between 1995-2001, and Eelam War IV between 2006-2009. See Muttukrishna Sarvananthaa in “Economy of the Conflict Region in Sri Lanka: From Embargo to Repression”, Policy Studies 44, East-West Centre, http://www.eastwestcenter.org/fileadmin/stored/pdfs/ps044.pdf. 3 “No end in sight to Sri Lanka conflict”, February 21, 2007, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/6382787.stm. 4 Amantha Perera, “Sri Lanka: Open War”, South Asia Intelligence Review, Volume 6, No.28, http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/sair/Archives/6_28.htm#assessment1. -

Nyhetskanalen I HD I Dag

03-09-2014 11:56 CEST Nyhetskanalen i HD i dag Fra i dag kan du se Nyhetskanalen i HD hos Get og Altibox. Canal Digital Kabel tilbyr HD-kanalen fra 23. september. TV 2 ønsker stadig å forbedre TV-opplevelsen for seerne, og vi kan i dag endelig lansere Norges eneste 24-timers nyhetskanal i HD-kvalitet. - Vi gleder oss over at Nyhetskanalen nå er tilgjengelig i HD hos Get og Altibox, mens Canal Digital Kabel gjør HD versjonen av kanalen tilgjengelig senere denne måneden. Vi jobber så raskt vi kan med å gjøre kanalen tilgjengelig også på satellitt og vi håper også på bakkenettet. Her kommer TV 2 Nyhetskanalen, sammen med både TV 2 Bliss og TV 2 Filmkanalen i HD senere i høst. Nyhetskanalen i HD vil i de aller fleste tilfeller ligge på samme kanalplass som SD versjonen har ligget i det digitale tilbudet. Følg ellers med på informasjon fra distributørene, forteller distribusjonssjef Ragnar Sørum i TV 2. Også nyhets- og sportsredaktør Jan Ove Årsæther gleder seg over at Nyhetskanalen nå er tilgjengelig i HD-kvalitet hos flere av distributørene. - Det jobbes nå hardt i mange avdelinger i TV 2 for å møte konkurransen som kommer. HD er et av områdene som har vært prioritet og vi er veldig glade for at dette nå er på plass. Vi er sikre på det bare vil forsterke den pene veksten Nyhetskanalen har hatt siste månedene, sier han. TV 2 ønsker å være tilstede på alle plattformer i best mulig bildekvalitet. Nylig ble Nyhetskanalen tilgjengelig i HD gjennom TV 2 Sumo på Apple TV. -

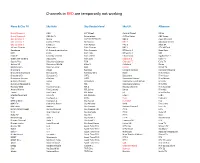

Channels in RED Are Temporarily Not Working

Channels in RED are temporarily not working Nova & Ote TV Sky Italy Sky Deutschland Sky UK Albanian Nova Cinema 1 AXN 13th Street Animal Planet 3 Plus Nova Cinema 2 AXN SciFi Boomerang At The Races ABC News Ote Cinema 1 Boing Cartoon Network BBC 1 Agon Channel Ote Cinema 2 Caccia e Pesca Discovery BBC 2 Albanian screen Ote Cinema 3 Canale 5 Film Action BBC 3 Alsat M Village Cinema Cartoonito Film Cinema BBC 4 ATV HDTurk Sundance CI Crime Investigation Film Comedy BT Sports 1 Bang Bang FOX Cielo Film Hits BT Sports 2 BBF FOXlife Comedy Central Film Select CBS Drama Big Brother 1 Greek VIP Cinema Discovery Film Star Channel 5 Club TV Sports Plus Discovery Science FOX Chelsea FC Cufo TV Action 24 Discovery World Kabel 1 Clubland Doma Motorvision Disney Junior Kika Colors Elrodi TV Discovery Dmax Nat Geo Comedy Central Explorer Shkence Discovery Showcase Eurosport 1 Nat Geo Wild Dave Film Aktion Discovery ID Eurosport 2 ORF1 Discovery Film Autor Discovery Science eXplora ORF2 Discovery History Film Drame History Channel Focus ProSieben Discovery Investigation Film Dy National Geographic Fox RTL Discovery Science Film Hits NatGeo Wild Fox Animation RTL 2 Disney Channel Film Komedi Animal Planet Fox Comedy RTL Crime Dmax Film Nje Travel Fox Crime RTL Nitro E4 Film Thriller E! Entertainment Fox Life RTL Passion Film 4 Folk+ TLC Fox Sport 1 SAT 1 Five Folklorit MTV Greece Fox Sport 2 Sky Action Five USA Fox MAD TV Gambero Rosso Sky Atlantic Gold Fox Crime MAD Hits History Sky Cinema History Channel Fox Life NOVA MAD Greekz Horror Channel Sky -

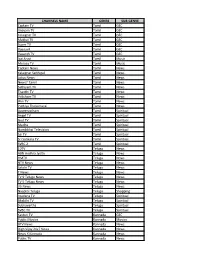

Channels Name

CHANNELS NAME GENRE SUB-GENRE Captain TV Tamil GEC Imayam TV Tamil GEC Kalaignar TV Tamil GEC Makkal TV Tamil GEC Super TV Tamil GEC Vaanavil Tamil GEC Vasanth TV Tamil GEC Isai Aruvi Tamil Music Murasu TV Tamil Music Captain News Tamil News Kalaignar Seithigal Tamil News Lotus News Tamil News News7 Tamil Tamil News Sathiyam TV Tamil News Thanthi TV Tamil News Velicham TV Tamil News Win TV Tamil News Puthiya Thalaimurai Tamil News Aaseervatham Tamil Spiritual Angel TV Tamil Spiritual God TV Tamil Spiritual Madha Tamil Spiritual Nambikkai Television Tamil Spiritual Sai TV Tamil Spiritual Sri Sankara TV Tamil Spiritual SVBC 2 Tamil Spiritual 10TV Telugu News ABN Andhra Jyothi Telugu News HMTV Telugu News NTV News Telugu News Sakshi TV Telugu News T News Telugu News TV 9 Telugu News Telugu News TV 5 Telugu News Telugu News V6 News Telugu News Naaptol Telugu Telugu Shopping Aradana TV Telugu Spiritual Bhakthi TV Telugu Spiritual Subhavartha Telugu Spiritual SVBC TV Telugu Spiritual Kasturi TV Kannada GEC Public Movies Kannada Movies BTV News Kannada News Digh Vijay 24x7 News Kannada News News X Kannada Kannada News Public TV Kannada News TV 9 Kannada Kannada News Suvarna News 24x7 Kannada News NT4 Kannada Shopping Amrita TV Malayalam GEC Jai Hind Malayalam GEC Kairali Malayalam GEC Kairali WE Malayalam GEC Kerala Vision Malayalam GEC Mangalam Malayalam GEC Mazhavil Manorama Malayalam GEC Mazhavil Manorama HD Malayalam GEC Reporter Malayalam GEC Flowers TV Malayalam GEC Asianet News Malayalam News Janam TV Malayalam News Kairali People Malayalam -

Ultimate Pack 7 Day Catch up BBC 1 Catchup BBC 1 HD

Ultimate Pack 7 Day Catch Up BBC 1 Catchup BBC 1 HD BBC 2 Catchup BBC 2 HD ITV 1 Catchup ITV 1 HD CH 4 Catchup CH 5 Catchup CH 5 HD SKY 1 Catchup SKY 1 HD SKY LIVING Catchup SKY ATLANTIC Catchup WATCH Catchup GOLD Catchup DAVE Catchup DAVE HD COMEDY CENTRAL UNIVERSAL SYFY BBC 4 Catchup ITV 2 Catchup ITV 3 Catchup ITV 4 SKY 2 Real Lives ITV Encore FOX TLC ALIBI COMEDY CTL EXTRA BT AMC Good Food S4C BBC ALBA E4 Catchup MORE 4 4SEVEN RTE 1 Catchup RTE 2 Catchup TV3 Catchup TG4 Catchup CHALLENGE CBS REALITY CBS DRAMA DMAX PICK TV LIFETIME SPIKE DRAMA QUEST FIVE USA Catchup FIVE STAR ITV BE TRUE DRAMA TRUE ENTERT' Sky Arts 1 SHED REALLY TRAVEL FOOD NETWORK SKY PREMIER Catchup SKY SHOWCASE SKY MODERN GREAT SKY MODERN GREAT HD SKY DISNEY Catchup SKY DISNEY HD SKY FAMILY Catchup SKY ACTION Catchup SKY COMEDY SKY CRIME & THRILLER SKY DRAMA SKY SCIFI SKY SELECT FILM 4 TRUE MOVIES 1 TRUE MOVIES 2 MOVIES 24 TCM MTV Hits MTV Rocks MTV CLASSIC VH1 MAGIC THE VAULT SCUZZ FLAVA VEVO 1 VEVO 2 VEVO 3 HEART CAPITAL RADIO SKY SPORT 1 SKY SPORT 1 HD SKY SPORT 2 SKY SPORT 2 HD SKY SPORT 3 SKY SPORT 3 HD SKY SPORT 4 SKY SPORT 4 HD SKY SPORT 5 SKY SPORT 5 HD SKY SPORT F1 SKY SPORT F1 HD SKY SPORT NEWS SKY SPORT NEWS HD EUROSPORT EUROSPORT HD EUROSPORT 2 BT SPORT 1 BT SPORT 1 HD BT SPORT 2 BT SPORT 2 HD BT EUROPE BT EUROPE HD BT SPORTS EXTRA BT ESPN AT THE RACES MUTV LIVERPOOL FC CHELSEA TV SETANTA IRELAND PREMIER SPORT RACING UK HORSE & COUNTRY MOTORS TV BOX NATION SKY NEWS BBC NEWS RT UK AL JAZEERA NEWS DISCOVERY Catchup DISCOVERY HD INVESTIGATION DISC ANIMAL PLANET DISC. -

Den Store TV-Krigen

Trine Syvertsen Den store TV-krigen Norsk allmennfjernsyn 1988-96 Uten navn-1 1 19.02.04, 15:17 Copyright © 1997 by Fagbokforlaget Vigmostad & Bjørke AS All Rights Reserved 2. opplag 2004 Printed in Poland OzGraf SA ISBN 82-7674-275-0 Omslagsdesign, layout og side- ombrekking er utført ved forlaget. Henvendelser om denne boken kan rettes til: Fagbokforlaget Postboks 6050 Postterminalen 5892 BERGEN Tlf.: 55 38 88 00 Faks: 55 38 88 01 e-post: [email protected] www.fagbokforlaget.no Det må ikke kopieres fra denne boken i strid med åndsverkloven eller i strid med avtaler om kopiering inngått med Kopinor, interesse- organ for rettighetshavere til åndsverk. Kolofn 2 25.02.04, 11:22 Forord Denne boka handler om endringene i norsk allmennfjernsyn fra slutten av 1980-tallet og fram til 1996. Mange har bidratt til at boka er blitt en realitet. Den største takken går til de medarbeiderne i NRK og TV2 som har latt seg intervjue i forbindelse med prosjektet. Takk for vennlig og tålmodig behandling og takk for at dere tok dere tid til å dele erfaringer og innsikter med meg. Jeg kan bare håpe at boka yter disse erfaringene og innsiktene rettferdighet. En spesiell takk går til dem som har gitt meg praktisk hjelp i de to kanalene. Dette gjelder særlig Thomas Barth og Birgit Eie i NRKs forskningsavdeling, og Harald Strømme og Arve Løberg i TV2. En stor takk går også til de mange andre som i løpet av prosjektperioden har opplyst meg om ulike sider ved norsk fjernsynsbransje. Dette gjelder øvrige medarbeidere i NRK, TV2 og andre kanaler, representanter for medie- forvaltningen og frittstående produksjonsselskap, dagspressejournalister og mediekritikere, og, ikke minst, venner, kolleger og familiemedlemmer. -

Meld. St. 38 (2014–2015) Tinging Av Publikasjonar

Meld. St. 38 (2014–2015) St. Meld. Tinging av publikasjonar Offentlege institusjonar: Tryggings- og serviceorganisasjonen til departementa Internett: www.publikasjoner.dep.no E-post: [email protected] Telefon: 22 24 00 00 Privat sektor: Internett: www.fagbokforlaget.no/offpub E-post: [email protected] Telefon: 55 38 66 00 Publikasjonane er også tilgjengelege på www.regjeringen.no Meld. St. 38 Trykk: 07 Aurskog – 06/2015 (2014–2015) Melding til Stortinget ØMERK J E Open og opplyst IL T M 2 4 9 1 7 3 Trykksak Open og opplyst Allmennkringkasting og mediemangfald Forsidebilder: Partilederdebatt på TV2. Foto: Fredrik Varfjell/NTB scanpix Masterchef TV3. Foto: Roger Neumann/VG TV2s høstlansering med Ida Fladen. Foto: Hallgeir Vågenes/VG Verdensrekord i værmelding med Eli Kari Gjengedal. Foto: Torstein Bøe/NTB scanpix Peter og Tomas Nortug. Foto: Ned Alley / NTB scanpix Fredrik Skavland i Kringkastingsrådet. Foto: Heiko Junge/NTB scanpix “The Voice” finalen på TV2. Foto: Trond Solberg/VG Lilyhammer. Foto: CapitalPictures DAB-radioer. Foto: Tore Meek/NTB scanpix Davy Wathne. Foto: Trond Reidar Teigen/NTB scanpix Netflix. Foto: Øyvind Gustavsen/VG Facebook. Foto: Stian Lysberg Solum/NTB scanpix Humor på TVNorge. Foto: Espen Solli/TVNorge. NTB Tema. Leo og Else Kåss Furuseth. Foto: NRK Nyhetsanker Paal R. Peterson. Foto: NRK Hurtigruta. Foto: NRK Tungtvannet. Foto: Jiri Hanzl/Filmkameratene AS Fantorangen. Foto: NRK Bildene er satt sammen av Lise Kihle Designsstudio AS Innhald 1 Bakgrunn og samandrag .......... 7 4.3 Gjeldande regulering i norsk rett .. 37 1.1 Bakgrunn ........................................ 7 4.3.1 Overordna ....................................... 37 1.1.1 Regjeringas overordna mål for 4.3.2 Nærare om NRK som lisens- mediepolitikken ............................ -

Bruce Blir Cait På TV 2 Bliss

16-07-2015 09:58 CEST Bruce blir Cait på TV 2 Bliss TV 2 Bliss skal til høsten vise den mye omtalte dokumentarserien «I am Cait» hvor vi følger Bruce Jenner i prosessen med å bli Caitlyn Jenner. TV 2 har sikret seg rettighetene til å sende den nye dokumentarserien «I Am Cait» fra NBCUniversal som følger Caitlyn Jenner (tidligere kjent som Bruce Jenner) tett på livet på veien fra mann til kvinne. Dokumentarserien forteller Caits svært personlige historie i det hun søker å finne sitt nye og egentlige jeg i en ny hverdag. For første gang kan hun leve som den personen hun føler at hun er født til å være. TV-serien ser også nærmere på hva Caits nye liv innebærer for familien og vennene rundt henne, og hvordan disse relasjonene påvirkes av at Bruce nå er Caitlyn. Serien er på åtte timelange episoder, og vil sendes på TV 2 Bliss til høsten. - TV 2 er strålende fornøyd med å ha sikret oss dette viktige og rørende innblikket i den tøffe reisen Bruce Jenner har satt ut på for å kunne bli Cait, og vi håper at serien kan være med på å bryte noen barrierer. Livet i Kardashians-familien har lenge vært viktig for TV 2 Bliss, og det er derfor veldig gledelig at vi kan følge denne herlige familien i denne nye serie, sier TV 2s direktør for internasjonale innkjøp, Nina Lorgen Flemmen. «I am Cait» er produsert av Bunim/Murray Productions. TV 2 er Norges største kommersielle tv-kanal og en av landets sterkeste merkevarer. -

Nyhetsbrev Uke 39

Nyhetsbrev TV uke 39 Nyhetsbrev uke 39 Tallene i dette nyhetsbrevet er for befolkningen 12 år og eldre (12+) samt personer 15-49 år. Begge disse målgruppene rapporteres i nasjonalt univers. Dersom du ønsker nærmere informasjon, kontakt: Mihai Dumitrescu. TV-seing i uke 39 Personer over 12 år så i gjennomsnitt 158 minutter på TV per dag i uke 39 og målgruppen 15-49 år så på TV i 126 minutter. Begge målgruppene hadde en nedgang i TV-seingen i forhold til foregående uke på henholdsvis 8 minutter og 6 minutter. NRK1 var største kanal i uke 39 med 24,8 % av den totale seertiden blant personer over 12 år i nasjonalt univers. Deretter følger TV2 med 22,5 % TVNORGE: 9,1 % TV3: 4,3 % Discovery: 1,1 %. Markedsandel% angir hvor stor del av den totale TV-seing hver enkelt kanal representerer. Kilde: TNS Gallup TV-undersøkelsen Nyhetsbrev TV uke 39 Kilde: TNS Gallup TV-undersøkelsen Nyhetsbrev TV uke 39 Utviklingen for kanalene i uke 39 2015 Grafikken viser utviklingen de siste to uker sammenlignet med de siste 52 uker. De mest sette TV-programmene per kanal i uke 39 2015 NRK1 Dato Tittel Seere (000) Index Alle 12+ Personer 15-49 1 25.09.15 Nytt på nytt 943 63 2 26.09.15 Stjernekamp 704 66 3 21.09.15 Dagsrevyen 702 30 4 25.09.15 Skavlan 693 52 5 27.09.15 Søndagsrevyen 682 39 6 22.09.15 Dagsrevyen 670 33 7 24.09.15 Dagsrevyen 646 37 8 23.09.15 Dagsrevyen 645 34 9 25.09.15 Norge rundt 619 41 10 25.09.15 Dagsrevyen 605 34 Kilde: TNS Gallup TV-undersøkelsen Nyhetsbrev TV uke 39 TV2 Seere (000) Index Dato Tittel Alle 12+ Personer 15-49 1 21.09.15 Farmen -

Samer I to Norske Nyhetsmedier

Samer i to norske nyhetsmedier En undersøkelse av saker med samisk hovedfokus i Nordlys og Dagsrevyen i perioden 1970–2000 Arne Johansen Ijäs Forord Slutten av 1900-tallet var en særdeles begivenhetsrik tid i samisk historie i Norge. Forsøkene på å knekke den samiske kulturen led sitt endelige nederlag, og i stedet vokste det fram en moderne samisk nasjon. Begivenhetene og prosessene som førte fram til denne utviklingen har etter hvert blitt gjenstand for oppmerksomheten til flere forskere, særlig ved Universitetet i Tromsø. Historikere, arkeologer, antropologer, samfunnsvi- tere, jurister og språkforskere har studert og søkt å forklare det som har skjedd både ved hjelp av studier i fortiden og nåtiden. Nyhetsmedier har de siste 30–40 år fått en stadig breiere plass i samfunnet, og i forbindelse med samenes kamp for sin nasjon har de utvilsomt spilt en viktig rolle både som bremsekloss og pådriver i proses- sen. De nasjonale medienes plass i samisk historie mot slutten av forrige hundreår har ikke vært gjenstand for omfattende studier til nå, og denne framstillingen er et lite bidrag til å se hendelsene fra et medieperspektiv. Framstillingen vil kunne brukes av studenter og forskere i mediefag og historie som ønsker å se på minoritetenes situasjon i majoritetssamfunnet. Jeg vil takke Norges Forskningsråd som gav meg et 3-årig stipend til å forske på disse spørsmål. Jeg vil også takke ledelsen ved Samisk høgskole, som helt siden jeg ble ansatt ved skolen i 2004, har gitt meg anledning til å arbeide med prosjektet. Min veileder professor Henry Minde ved Universitetet i Tromsø har også vært til stor hjelp, og korrigert meg når det har båret galt av sted.