Circulation in the Arctic Ocean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Improved Bathymetric Portrayal of the Arctic Ocean

GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH LETTERS, VOL. 35, L07602, doi:10.1029/2008GL033520, 2008 An improved bathymetric portrayal of the Arctic Ocean: Implications for ocean modeling and geological, geophysical and oceanographic analyses Martin Jakobsson,1 Ron Macnab,2,3 Larry Mayer,4 Robert Anderson,5 Margo Edwards,6 Jo¨rn Hatzky,7 Hans Werner Schenke,7 and Paul Johnson6 Received 3 February 2008; revised 28 February 2008; accepted 5 March 2008; published 3 April 2008. [1] A digital representation of ocean floor topography is icebreaker cruises conducted by Sweden and Germany at the essential for a broad variety of geological, geophysical and end of the twentieth century. oceanographic analyses and modeling. In this paper we [3] Despite all the bathymetric soundings that became present a new version of the International Bathymetric available in 1999, there were still large areas of the Arctic Chart of the Arctic Ocean (IBCAO) in the form of a digital Ocean where publicly accessible depth measurements were grid on a Polar Stereographic projection with grid cell completely absent. Some of these areas had been mapped by spacing of 2 Â 2 km. The new IBCAO, which has been agencies of the former Soviet Union, but their soundings derived from an accumulated database of available were classified and thus not available to IBCAO. Depth bathymetric data including the recent years of multibeam information in these areas was acquired by digitizing the mapping, significantly improves our portrayal of the Arctic isobaths that appeared on a bathymetric map which was Ocean seafloor. Citation: Jakobsson, M., R. Macnab, L. Mayer, derived from the classified Russian mapping missions, and R. -

North America Other Continents

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

Marine Ecology Progress Series 600:21

Vol. 600: 21–39, 2018 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published July 30 https://doi.org/10.3354/meps12663 Mar Ecol Prog Ser OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Short-term processing of ice algal- and phytoplankton- derived carbon by Arctic benthic communities revealed through isotope labelling experiments Anni Mäkelä1,*, Ursula Witte1, Philippe Archambault2 1School of Biological Sciences, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen AB24 3UU, UK 2Département de biologie, Québec Océan, Université Laval, Québec, QC G1V 0A6, Canada ABSTRACT: Benthic ecosystems play a significant role in the carbon (C) cycle through remineral- ization of organic matter reaching the seafloor. Ice algae and phytoplankton are major C sources for Arctic benthic consumers, but climate change-mediated loss of summer sea ice is predicted to change Arctic marine primary production by increasing phytoplankton and reducing ice algal contributions. To investigate the impact of changing algal C sources on benthic C processing, 2 isotope tracing experiments on 13C-labelled ice algae and phytoplankton were conducted in the North Water Polynya (NOW; 709 m depth) and Lancaster Sound (LS; 794 m) in the Canadian Arc- tic, during which the fate of ice algal (CIA) and phytoplankton (CPP) C added to sediment cores was traced over 4 d. No difference in sediment community oxygen consumption (SCOC, indicative of total C turnover) between the background measurements and ice algal or phytoplankton cores was found at either site. Most of the processed algal C was respired, with significantly more CPP than CIA being released as dissolved inorganic C at both sites. Macroinfaunal uptake of algal C was minor, but bacterial assimilation accounted for 33−44% of total algal C processing, with no differences in bacterial uptake of CPP and CIA found at either site. -

Eurythenes Gryllus Reveal a Diverse Abyss and a Bipolar Species

OPEN 3 ACCESS Freely available online © PLOSI o - Genetic and Morphological Divergences in the Cosmopolitan Deep-Sea AmphipodEurythenes gryllus Reveal a Diverse Abyss and a Bipolar Species Charlotte Havermans1'3*, Gontran Sonet2, Cédric d'Udekem d'Acoz2, Zoltán T. Nagy2, Patrick Martin1'2, Saskia Brix4, Torben Riehl4, Shobhit Agrawal5, Christoph Held5 1 Direction Natural Environment, Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Brussels, Belgium, 2 Direction Taxonomy and Phylogeny, Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Brussels, Belgium, 3 Biodiversity Research Centre, Earth and Life Institute, Catholic University of Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 4C entre for Marine Biodiversity Research, Senckenberg Research Institute c/o Biocentrum Grindel, Hamburg, Germany, 5 Section Functional Ecology, Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, Germany Abstract Eurythenes gryllus is one of the most widespread amphipod species, occurring in every ocean with a depth range covering the bathyal, abyssal and hadai zones. Previous studies, however, indicated the existence of several genetically and morphologically divergent lineages, questioning the assumption of its cosmopolitan and eurybathic distribution. For the first time, its genetic diversity was explored at the global scale (Arctic, Atlantic, Pacific and Southern oceans) by analyzing nuclear (28S rDNA) and mitochondrial (COI, 16S rDNA) sequence data using various species delimitation methods in a phylogeographic context. Nine putative species-level clades were identified within £ gryllus. A clear distinction was observed between samples collected at bathyal versus abyssal depths, with a genetic break occurring around 3,000 m. Two bathyal and two abyssal lineages showed a widespread distribution, while five other abyssal lineages each seemed to be restricted to a single ocean basin. -

Bathymetry and Deep-Water Exchange Across the Central Lomonosov Ridge at 88–891N

ARTICLE IN PRESS Deep-Sea Research I 54 (2007) 1197–1208 www.elsevier.com/locate/dsri Bathymetry and deep-water exchange across the central Lomonosov Ridge at 88–891N Go¨ran Bjo¨rka,Ã, Martin Jakobssonb, Bert Rudelsc, James H. Swiftd, Leif Andersone, Dennis A. Darbyf, Jan Backmanb, Bernard Coakleyg, Peter Winsorh, Leonid Polyaki, Margo Edwardsj aGo¨teborg University, Earth Sciences Center, Box 460, SE-405 30 Go¨teborg, Sweden bDepartment of Geology and Geochemistry, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden cFinnish Institute for Marine Research, Helsinki, Finland dScripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA eDepartment of Chemistry, Go¨teborg University, Go¨teborg, Sweden fDepartment of Ocean, Earth, & Atmospheric Sciences, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, USA gDepartment of Geology and Geophysics, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, USA hPhysical Oceanography Department, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA, USA iByrd Polar Research Center, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA jHawaii Institute of Geophysics and Planetology, University of Hawaii, HI, USA Received 23 October 2006; received in revised form 9 May 2007; accepted 18 May 2007 Available online 2 June 2007 Abstract Seafloor mapping of the central Lomonosov Ridge using a multibeam echo-sounder during the Beringia/Healy–Oden Trans-Arctic Expedition (HOTRAX) 2005 shows that a channel across the ridge has a substantially shallower sill depth than the 2500 m indicated in present bathymetric maps. The multibeam survey along the ridge crest shows a maximum sill depth of about 1870 m. A previously hypothesized exchange of deep water from the Amundsen Basin to the Makarov Basin in this area is not confirmed. -

Satellite Ice Extent, Sea Surface Temperature, and Atmospheric 2 Methane Trends in the Barents and Kara Seas

The Cryosphere Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-2018-237 Manuscript under review for journal The Cryosphere Discussion started: 22 November 2018 c Author(s) 2018. CC BY 4.0 License. 1 Satellite ice extent, sea surface temperature, and atmospheric 2 methane trends in the Barents and Kara Seas 1 2 3 2 4 3 Ira Leifer , F. Robert Chen , Thomas McClimans , Frank Muller Karger , Leonid Yurganov 1 4 Bubbleology Research International, Inc., Solvang, CA, USA 2 5 University of Southern Florida, USA 3 6 SINTEF Ocean, Trondheim, Norway 4 7 University of Maryland, Baltimore, USA 8 Correspondence to: Ira Leifer ([email protected]) 9 10 Abstract. Over a decade (2003-2015) of satellite data of sea-ice extent, sea surface temperature (SST), and methane 11 (CH4) concentrations in lower troposphere over 10 focus areas within the Barents and Kara Seas (BKS) were 12 analyzed for anomalies and trends relative to the Barents Sea. Large positive CH4 anomalies were discovered around 13 Franz Josef Land (FJL) and offshore west Novaya Zemlya in early fall. Far smaller CH4 enhancement was found 14 around Svalbard, downstream and north of known seabed seepage. SST increased in all focus areas at rates from 15 0.0018 to 0.15 °C yr-1, CH4 growth spanned 3.06 to 3.49 ppb yr-1. 16 The strongest SST increase was observed each year in the southeast Barents Sea in June due to strengthening of 17 the warm Murman Current (MC), and in the south Kara Sea in September. The southeast Barents Sea, the south 18 Kara Sea and coastal areas around FJL exhibited the strongest CH4 growth over the observation period. -

New Siberian Islands Archipelago)

Detrital zircon ages and provenance of the Upper Paleozoic successions of Kotel’ny Island (New Siberian Islands archipelago) Victoria B. Ershova1,*, Andrei V. Prokopiev2, Andrei K. Khudoley1, Nikolay N. Sobolev3, and Eugeny O. Petrov3 1INSTITUTE OF EARTH SCIENCE, ST. PETERSBURG STATE UNIVERSITY, UNIVERSITETSKAYA NAB. 7/9, ST. PETERSBURG 199034, RUSSIA 2DIAMOND AND PRECIOUS METAL GEOLOGY INSTITUTE, SIBERIAN BRANCH, RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, LENIN PROSPECT 39, YAKUTSK 677980, RUSSIA 3RUSSIAN GEOLOGICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE (VSEGEI), SREDNIY PROSPECT 74, ST. PETERSBURG 199106, RUSSIA ABSTRACT Plate-tectonic models for the Paleozoic evolution of the Arctic are numerous and diverse. Our detrital zircon provenance study of Upper Paleozoic sandstones from Kotel’ny Island (New Siberian Island archipelago) provides new data on the provenance of clastic sediments and crustal affinity of the New Siberian Islands. Upper Devonian–Lower Carboniferous deposits yield detrital zircon populations that are consistent with the age of magmatic and metamorphic rocks within the Grenvillian-Sveconorwegian, Timanian, and Caledonian orogenic belts, but not with the Siberian craton. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test reveals a strong similarity between detrital zircon populations within Devonian–Permian clastics of the New Siberian Islands, Wrangel Island (and possibly Chukotka), and the Severnaya Zemlya Archipelago. These results suggest that the New Siberian Islands, along with Wrangel Island and the Severnaya Zemlya Archipelago, were located along the northern margin of Laurentia-Baltica in the Late Devonian–Mississippian and possibly made up a single tectonic block. Detrital zircon populations from the Permian clastics record a dramatic shift to a Uralian provenance. The data and results presented here provide vital information to aid Paleozoic tectonic reconstructions of the Arctic region prior to opening of the Mesozoic oceanic basins. -

Geography Notes.Pdf

THE GLOBE What is a globe? a small model of the Earth Parts of a globe: equator - the line on the globe halfway between the North Pole and the South Pole poles - the northern-most and southern-most points on the Earth 1. North Pole 2. South Pole hemispheres - half of the earth, divided by the equator (North & South) and the prime meridian (East and West) 1. Northern Hemisphere 2. Southern Hemisphere 3. Eastern Hemisphere 4. Western Hemisphere continents - the largest land areas on Earth 1. North America 2. South America 3. Europe 4. Asia 5. Africa 6. Australia 7. Antarctica oceans - the largest water areas on Earth 1. Atlantic Ocean 2. Pacific Ocean 3. Indian Ocean 4. Arctic Ocean 5. Antarctic Ocean WORLD MAP ** NOTE: Our textbooks call the “Southern Ocean” the “Antarctic Ocean” ** North America The three major countries of North America are: 1. Canada 2. United States 3. Mexico Where Do We Live? We live in the Western & Northern Hemispheres. We live on the continent of North America. The other 2 large countries on this continent are Canada and Mexico. The name of our country is the United States. There are 50 states in it, but when it first became a country, there were only 13 states. The name of our state is New York. Its capital city is Albany. GEOGRAPHY STUDY GUIDE You will need to know: VOCABULARY: equator globe hemisphere continent ocean compass WORLD MAP - be able to label 7 continents and 5 oceans 3 Large Countries of North America 1. United States 2. Canada 3. -

New Hydrographic Measurements of the Upper Arctic Western Eurasian

New Hydrographic Measurements of the Upper Arctic Western Eurasian Basin in 2017 Reveal Fresher Mixed Layer and Shallower Warm Layer Than 2005–2012 Climatology Marylou Athanase, Nathalie Sennéchael, Gilles Garric, Zoé Koenig, Elisabeth Boles, Christine Provost To cite this version: Marylou Athanase, Nathalie Sennéchael, Gilles Garric, Zoé Koenig, Elisabeth Boles, et al.. New Hy- drographic Measurements of the Upper Arctic Western Eurasian Basin in 2017 Reveal Fresher Mixed Layer and Shallower Warm Layer Than 2005–2012 Climatology. Journal of Geophysical Research. Oceans, Wiley-Blackwell, 2019, 124 (2), pp.1091-1114. 10.1029/2018JC014701. hal-03015373 HAL Id: hal-03015373 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03015373 Submitted on 19 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. RESEARCH ARTICLE New Hydrographic Measurements of the Upper Arctic 10.1029/2018JC014701 Western Eurasian Basin in 2017 Reveal Fresher Mixed Key Points: – • Autonomous profilers provide an Layer and Shallower Warm Layer Than 2005 extensive physical and biogeochemical -

The Eu and the Arctic

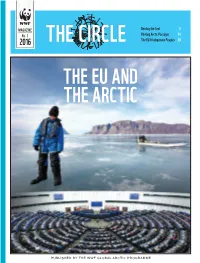

MAGAZINE Dealing the Seal 8 No. 1 Piloting Arctic Passages 14 2016 THE CIRCLE The EU & Indigenous Peoples 20 THE EU AND THE ARCTIC PUBLISHED BY THE WWF GLOBAL ARCTIC PROGRAMME TheCircle0116.indd 1 25.02.2016 10.53 THE CIRCLE 1.2016 THE EU AND THE ARCTIC Contents EDITORIAL Leaving a legacy 3 IN BRIEF 4 ALYSON BAILES What does the EU want, what can it offer? 6 DIANA WALLIS Dealing the seal 8 ROBIN TEVERSON ‘High time’ EU gets observer status: UK 10 ADAM STEPIEN A call for a two-tier EU policy 12 MARIA DELIGIANNI Piloting the Arctic Passages 14 TIMO KOIVUROVA Finland: wearing two hats 16 Greenland – walking the middle path 18 FERNANDO GARCES DE LOS FAYOS The European Parliament & EU Arctic policy 19 CHRISTINA HENRIKSEN The EU and Arctic Indigenous peoples 20 NICOLE BIEBOW A driving force: The EU & polar research 22 THE PICTURE 24 The Circle is published quar- Publisher: Editor in Chief: Clive Tesar, COVER: terly by the WWF Global Arctic WWF Global Arctic Programme [email protected] (Top:) Local on sea ice in Uumman- Programme. Reproduction and 8th floor, 275 Slater St., Ottawa, naq, Greenland. quotation with appropriate credit ON, Canada K1P 5H9. Managing Editor: Becky Rynor, Photo: Lawrence Hislop, www.grida.no are encouraged. Articles by non- Tel: +1 613-232-8706 [email protected] (Bottom:) European Parliament, affiliated sources do not neces- Fax: +1 613-232-4181 Strasbourg, France. sarily reflect the views or policies Design and production: Photo: Diliff, Wikimedia Commonss of WWF. Send change of address Internet: www.panda.org/arctic Film & Form/Ketill Berger, and subscription queries to the [email protected] ABOVE: Sarek glacier, Sarek National address on the right. -

A Newly Discovered Glacial Trough on the East Siberian Continental Margin

Clim. Past Discuss., doi:10.5194/cp-2017-56, 2017 Manuscript under review for journal Clim. Past Discussion started: 20 April 2017 c Author(s) 2017. CC-BY 3.0 License. De Long Trough: A newly discovered glacial trough on the East Siberian Continental Margin Matt O’Regan1,2, Jan Backman1,2, Natalia Barrientos1,2, Thomas M. Cronin3, Laura Gemery3, Nina 2,4 5 2,6 7 1,2,8 9,10 5 Kirchner , Larry A. Mayer , Johan Nilsson , Riko Noormets , Christof Pearce , Igor Semilietov , Christian Stranne1,2,5, Martin Jakobsson1,2. 1 Department of Geological Sciences, Stockholm University, Stockholm, 106 91, Sweden 2 Bolin Centre for Climate Research, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden 10 3 US Geological Survey MS926A, Reston, Virginia, 20192, USA 4 Department of Physical Geography (NG), Stockholm University, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 5 Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping, University of New Hampshire, New Hampshire 03824, USA 6 Department of Meteorology, Stockholm University, Stockholm, 106 91, Sweden 7 University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS), P O Box 156, N-9171 Longyearbyen, Svalbard 15 8 Department of Geoscience, Aarhus University, Aarhus, 8000, Denmark 9 Pacific Oceanological Institute, Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 690041 Vladivostok, Russia 10 Tomsk National Research Polytechnic University, Tomsk, Russia Correspondence to: Matt O’Regan ([email protected]) 20 Abstract. Ice sheets extending over parts of the East Siberian continental shelf have been proposed during the last glacial period, and during the larger Pleistocene glaciations. The sparse data available over this sector of the Arctic Ocean has left the timing, extent and even existence of these ice sheets largely unresolved. -

Chapter 7 Arctic Oceanography; the Path of North Atlantic Deep Water

Chapter 7 Arctic oceanography; the path of North Atlantic Deep Water The importance of the Southern Ocean for the formation of the water masses of the world ocean poses the question whether similar conditions are found in the Arctic. We therefore postpone the discussion of the temperate and tropical oceans again and have a look at the oceanography of the Arctic Seas. It does not take much to realize that the impact of the Arctic region on the circulation and water masses of the World Ocean differs substantially from that of the Southern Ocean. The major reason is found in the topography. The Arctic Seas belong to a class of ocean basins known as mediterranean seas (Dietrich et al., 1980). A mediterranean sea is defined as a part of the world ocean which has only limited communication with the major ocean basins (these being the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans) and where the circulation is dominated by thermohaline forcing. What this means is that, in contrast to the dynamics of the major ocean basins where most currents are driven by the wind and modified by thermohaline effects, currents in mediterranean seas are driven by temperature and salinity differences (the salinity effect usually dominates) and modified by wind action. The reason for the dominance of thermohaline forcing is the topography: Mediterranean Seas are separated from the major ocean basins by sills, which limit the exchange of deeper waters. Fig. 7.1. Schematic illustration of the circulation in mediterranean seas; (a) with negative precipitation - evaporation balance, (b) with positive precipitation - evaporation balance.