Pop and Politics in Late Soviet Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lenin and the Russian Civil War

Lenin and the Russian Civil War In the months and years after the fall of Tsar Nicholas II’s government, Russia went through incredible, often violent changes. The society was transformed from a peasant society run by an absolute monarchy into a worker’s state run by an all- powerful group that came to be known as the Communist Party. A key to this transformation is Vladimir Lenin. Who Was Lenin? • Born into a wealthy middle-class family background. • Witnessed (when he was 17) the hanging of his brother Aleksandr for revolutionary activity. • Kicked out his university for participating in anti- Tsarist protests. • Took and passed his law exams and served in various law firms in St. Petersburg and elsewhere. • Arrested and sent to Siberia for 3 years for transporting and distributing revolutionary literature. • When WWI started, argued that it should become a revolution of the workers throughout Europe. • Released and lived mostly in exile (Switzerland) until 1917. • Adopted the name “Lenin” (he was born Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov) in exile to hide his activities from the Tsar’s secret police. Lenin and the French Revolution Lenin admired the revolutionaries in France 100 years before his time, though he believed they didn’t go far enough – too much wealth was left in middle class hands. His Bolsheviks used the chaotic and incomplete nature of the French Revolution as a guide - they believed that in order for a communist revolution to succeed, it would need firm leadership from a small group of party leaders – a very different vision from Karl Marx. So, in some ways, Lenin was like Robin Hood – taking from the rich and giving to the poor. -

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Bronze Soldier April Crisis

LEGAL INFORMATION CENTRE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS BRONZE SOLDIER APRIL CRISIS ISBN 978-9985-9542-7-0 TALLINN, 2007 BRONZE SOLDIER. April crisis сontentS PREFACE . 7 WAR OF THE MONUMENTS: A CHRONOLOGICAL REVIEW . 10 APRIL RIOTS IN TaLLINN: LEGAL ASPECTS . .24 Part I. LEGAL FRAMEWORK . 24 Part II. OVERVIEW OF APPLICATIONS AGAINST THE ACTIONS OF LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICIALS . 29 AFTERWORD . 43 ANNEX I . 44 ANNEX II . .50 6 PREFACE There is no doubt that the April events concerning the Bronze Soldier will become a benchmark in the contemporary history of the state of Estonia. It is the bifurcation point, the point of division, separating ‘before’ and ‘after’. For Estonian society these events are even more important than joining NATO or European Union. Before April 2007 we lived in one country and now we are getting used to living in another one. Or were these merely illusions and as Eugeny Golikov wrote «the world has not changed, it has just partially revealed its face» («Tallinn», no. 2‑3, 2007)? Before April 26, 2007 we, the population of Estonia, believed that we lived in a democratic country, with proper separation of powers, with efficiently balanced executive and legislative powers, with independent courts, a free press, social control over government, in particular over the security agencies, and so on. After April 26 it turned out that not all this was true, or was not exactly true, or was even false. It turned out that some mechanisms, considered deeply rooted in the democratic society, had no effect and some procedures were easily abandoned. Just one example: by order of the Police Prefect, all public rallies and meetings in Tallinn were prohibited from April 30 till May 11, 2007 and it did not result in any protests or even questions, although this was a restriction of the constitutional right to express opinions, the right of peaceful assembly, rally and demonstration. -

Russian, Jewish Or Human? Jewish Mystical Thought in the Poetry of Bulat Shalvovich Okudzhava

RUSSIAN, JEWISH OR HUMAN? JEWISH MYSTICAL THOUGHT IN THE POETRY OF BULAT SHALVOVICH OKUDZHAVA Katarzyna anna KornacKa-Sareło1 (Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań) Keywords: Bulat Shalvovich Okudzhava, poetry, imagology, Jewish mysticism, Jewish philosophy of dialogue Słowa kluczowe: Bułat Okudżawa, poezja, imagologia, mistycyzm żydowski, żydowska filozofia dialogu Abstract: Katarzyna Anna Kornacka-Sareło, RUSSIAN, JEWISH OR HUMAN? JEWISH MYSTI- CAL THOUGHT IN THE POETRY OF BULAT SHALVOVICH OKUDZHAVA. “PORÓWNA- NIA” 2 (21), 2017, P. 197–214. ISSN 1733-165X. While looking at the literary output of Bulat Shal- vovich Okudzhava from the perspective of imagology, one can see that the image of “the Other” in the poems of the Russian bard was created, paradoxically, just by this “Other”, and it was not constructed by the images (imagines) intrinsically present in the consciousness of the ethnocentric “Self” or “The Same”. In other words, in the case of Okudzhava’s poetry, the image of “the Other” stands on the basis of some ideas of Jewish mystics and the ones of Jewish philosophers of dia- logue (Martin Buber, Franz Rosenzweig and Emmanuel Lévinas). Therefore, the aim of this article was to present the motifs stemming from Jewish mysticism in the poems-songs by Okudzhava which, as it seems, influenced theological, anthropological and ethical views of the bard. The distinctive feature of Okudzhava’s philosophical approach is perceiving every person, regardless of their ethnic or cultural origin, as a being responsible for themselves in the process of constitut- ing themselves in their humanity. The same person is also responsible for other people, for the world of nature, and even for an impersonal and non-anthropomorphic godhead who does not intervene in human affairs. -

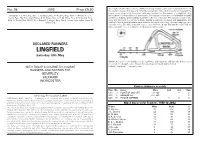

Lingfield Park Round Course Is a Left-Handed Loop of About a Mile and a Half, Which Intersects No

The Lingfield Park round course is a left-handed loop of about a mile and a half, which intersects No. 96 2003 Price £5.50 the straight of seven furlongs and 140 yards nearly half a mile out. For nearly half its length the round course is quite flat, then rises with easy gradients to the summit of a slight hill, after Stewards J. J. Aird, Esq., M. C. C. Armitage, Esq., R. Hacking, Esq., The Lord Pender, K. C. S. which there is a downhill turn to the straight. The straight course has a considerable downhill Young, Esq., The Hon. Adam Barker, D. W. Wates, Esq., A. H. M. White, Esq., N. R. Nutting, Esq., gradient to halfway, and is slightly downhill for the rest of the way. The straight course is very D. M. K. Tindall, Esq., Mrs R. W. S. Baker, D. J. Veasey, Esq., Mrs S. Leader, Lady Celina Carter, D. easy, and the track as a whole is sharp, putting a premium on speed and adaptability, and Adam, Esq. making relatively small demands upon stamina, though this does not, of course, apply to races over two miles. The mile-and-a-half course, over which the Derby Trial and the Oaks Trial are run, bears quite close resemblance to the Epsom Derby course. DECLARED RUNNERS LINGFIELD Saturday 10th May DRAW: As has been the tradition on the turf track, high numbers still have the better recent record on the straight course, though the advantage isn’t particularly marked. WITH TODAY’S COURSE-TO-COURSE STALLS: Stand side — straight course. -

Introduction Land Reform in Post-Communist Europe

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87938-5 - The Post-Soviet Potemkin Village: Politics and Property Rights in the Black Earth Jessica Allina-Pisano Excerpt More information Introduction Land Reform in Post-Communist Europe In December 1991, as the flag of the Soviet Union flew its last days over the Kremlin, a small crowd armed with crutches and wheelchair wheels stormed the regional state administration building in an eastern Ukrainian city. The city, Kharkiv, lies fifty miles from the Russian border.1 The protesters were a group of senior citizens and disabled people from the Saltivka housing development in Moskovsky district, an area of the city named for its location on the road to the Soviet metropolis. The group had gathered to demand land for garden plots. The protesters had specific land in mind. The land lay at the eastern edge of the city, bordering the Saltivka housing development to the west and the fields of one of the most successful agricultural collectives in the region to the east. That farm, named Ukrainka, was among the biggest dairy producers in the area. Food supplies in city markets, however, had become unpredictable and expensive. Residents of Saltivka wanted land to grow produce for themselves and their families. In response, the Kharkiv district executive committee ordered that Ukrainka relinquish nearly 300 hectares of land for garden plots, in addition to 75 hectares already alienated for that purpose the previous spring. Members of the Ukrainka collective objected to the proposed plan, 1 This account is based on a series of newspaper articles about the incident in a Kharkiv regional paper: M. -

Songs of the Mighty Five: a Guide for Teachers and Performers

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IUScholarWorks SONGS OF THE MIGHTY FIVE: A GUIDE FOR TEACHERS AND PERFORMERS BY SARAH STANKIEWICZ DAILEY Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music, Indiana University July, 2013 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music. ___________________________________ Ayana Smith, Research Director __________________________________ Mary Ann Hart, Chairperson __________________________________ Marietta Simpson __________________________________ Patricia Stiles ii Copyright © 2013 Sarah Stankiewicz Dailey iii To Nathaniel iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express many thanks and appreciation to the members of my committee—Dr. Ayana Smith, Professor Mary Ann Hart, Professor Marietta Simpson, and Professor Patricia Stiles—for their support, patience, and generous assistance throughout the course of this project. My special appreciation goes to Professor Hart for her instruction and guidance throughout my years of private study and for endowing me with a love of song literature. I will always be grateful to Dr. Estelle Jorgensen for her role as a mentor in my educational development and her constant encouragement in the early years of my doctoral work. Thanks also to my longtime collaborator, Karina Avanesian, for first suggesting the idea for the project and my fellow doctoral students for ideas, advice, and inspiration. I am also extremely indebted to Dr. Craig M. Grayson, who graciously lent me sections of his dissertation before it was publically available. Finally, my deepest gratitude goes to my family for love and support over the years and especially my husband, Nathaniel, who has always believed in me. -

Vinyls-Collection.Com Page 1/222 - Total : 8629 Vinyls Au 05/10/2021 Collection "Artistes Divers Toutes Catã©Gorie

Collection "Artistes divers toutes catégorie. TOUT FORMATS." de yvinyl Artiste Titre Format Ref Pays de pressage !!! !!! LP GSL39 Etats Unis Amerique 10cc Windows In The Jungle LP MERL 28 Royaume-Uni 10cc The Original Soundtrack LP 9102 500 France 10cc Ten Out Of 10 LP 6359 048 France 10cc Look Hear? LP 6310 507 Allemagne 10cc Live And Let Live 2LP 6641 698 Royaume-Uni 10cc How Dare You! LP 9102.501 France 10cc Deceptive Bends LP 9102 502 France 10cc Bloody Tourists LP 9102 503 France 12°5 12°5 LP BAL 13015 France 13th Floor Elevators The Psychedelic Sounds LP LIKP 003 Inconnu 13th Floor Elevators Live LP LIKP 002 Inconnu 13th Floor Elevators Easter Everywhere LP IA 5 Etats Unis Amerique 18 Karat Gold All-bumm LP UAS 29 559 1 Allemagne 20/20 20/20 LP 83898 Pays-Bas 20th Century Steel Band Yellow Bird Is Dead LP UAS 29980 France 3 Hur-el Hürel Arsivi LP 002 Inconnu 38 Special Wild Eyed Southern Boys LP 64835 Pays-Bas 38 Special W.w. Rockin' Into The Night LP 64782 Pays-Bas 38 Special Tour De Force LP SP 4971 Etats Unis Amerique 38 Special Strength In Numbers LP SP 5115 Etats Unis Amerique 38 Special Special Forces LP 64888 Pays-Bas 38 Special Special Delivery LP SP-3165 Etats Unis Amerique 38 Special Rock & Roll Strategy LP SP 5218 Etats Unis Amerique 45s (the) 45s CD hag 009 Inconnu A Cid Symphony Ernie Fischbach And Charles Ew...3LP AK 090/3 Italie A Euphonius Wail A Euphonius Wail LP KS-3668 Etats Unis Amerique A Foot In Coldwater Or All Around Us LP 7E-1025 Etats Unis Amerique A's (the A's) The A's LP AB 4238 Etats Unis Amerique A.b. -

XXIX Days of Estonian Jurisprudents 15 Years of Legal Reforms in Estonia Tartu, 19–20 October 2006

XXIX Days of Estonian Jurisprudents 15 Years of Legal Reforms in Estonia Tartu, 19–20 October 2006 JURIDICA INTERNATIONAL XI/2006 195 XXIX Days of Estonian Jurisprudents Thursday, 19 October 9.0010.00 Registration and morning coffee 10.00 Opening address by Rein Lang, Minister of Justice Morning plenary (Vanemuine Concert Hall) Chairs: Professor Kalle Merusk, Dean, Faculty of Law, University of Tartu; Chairman of the Estonian Academic Law Society Ingrid Siimann, Acting President of the Estonian Lawyers Union 10.1510.40 Ph.D. Jüri Raidla Start of Legal Reforms: from the War of Laws to the Constitution Attorney-at-law, Law Office Raidla & Partners 10.4011.05 Professor Jean-Pierre Massias The Role of Constitutional Law in Democratic Transition Process University of Auvergne (Clermont-Ferrand), Editor of the journal La Revue de Justice Constitutionnelle Est-Européenne 11.0511.30 Professor Paul Varul New Private Law Why This and What will Happen Next? Professor of Civil Law, University of Tartu; Editor-in-chief of the journals Juridica and Juridica International Afternoon plenary (Vanemuine Concert Hall) Chairs: Märt Rask, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Priidu Pärna, Member of Presidency, Estonian Lawyers Union 12.0012.25 Professor Valentinas Mikelenas Civil Law and Civil Procedural Law Reforms in Lithuania Professor, University of Vilnius 12.2512.50 Dr.iur. Hannes Veinla Environmental Impact of Development Projects: Economy versus the Environment Docent of Environmental Law, University of Tartu 12.5013.15 Martin Hirvoja Updating Economic Crime Law in Estonia Foundations and Emphases Deputy Secretary General of Criminal Policy, Ministry of Justice 196 JURIDICA INTERNATIONAL XI/2006 XXIX Days of Estonian Jurisprudents First private law section Interpretation and Implementation Problems Related to the Law of Obligations (Vanemuine Concert Hall) Chairs: Professor Paul Varul, Professor of Civil Law, University of Tartu Aivar Pilv, Chairman, Estonian Bar Association 15.0015.20 Mag.iur. -

Sbornik Rabot Konferentsii Zhiv

Republic Public Organization "Belarusian Association of UNESCO Clubs" Educational Institution "The National Artwork Center for Children and Youth" The Committee "Youth and UNESCO Clubs" of the National Commission of the Republic of Belarus for UNESCO European Federation of UNESCO Clubs, Centers and Associations International Youth Conference "Living Heritage" Collection of scientific articles on the conference "Living Heritage" Minsk, April 27 2014 In the collection of articles of international scientific-practical conference «Living Heritage» are examined the distinct features of the intangible cultural heritage of Belarus and different regions of Europe, the attention of youth is drawn to the problems of preservation, support and popularization of intangible culture.The articles are based on data taken from literature, experience and practice. All the presented materials can be useful for under-graduate and post- graduate students, professors in educational process and scientific researches in the field of intangible cultural heritage. The Conference was held on April 27, 2014 under the project «Participation of youth in the preservation of intangible cultural heritage» at the UO "The National Artwork Center for children and youth" in Minsk. The participants of the conference were 60 children at the age of 15-18 from Belarus, Armenia, Romania, and Latvia. The conference was dedicated to the 60th anniversary membership of the Republic Belarus at UNESCO and the 25th anniversary of the Belarusian Association of UNESCO Clubs. Section 1.Oral Traditions and Language Mysteries of Belarusian Castles OlgaMashnitskaja,form 10 A, School № 161Minsk. AnnaKarachun, form 10 A, School № 161 Minsk. Belarus is the charming country with ancient castles, monuments, sights and other attractions. -

SOVIET YOUTH FILMS UNDER BREZHNEV: WATCHING BETWEEN the LINES by Olga Klimova Specialist Degree, Belarusian State University

SOVIET YOUTH FILMS UNDER BREZHNEV: WATCHING BETWEEN THE LINES by Olga Klimova Specialist degree, Belarusian State University, 2001 Master of Arts, Brock University, 2005 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Olga Klimova It was defended on May 06, 2013 and approved by David J. Birnbaum, Professor, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Pittsburgh Lucy Fischer, Distinguished Professor, Department of English, University of Pittsburgh Vladimir Padunov, Associate Professor, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Pittsburgh Aleksandr Prokhorov, Associate Professor, Department of Modern Languages and Literatures, College of William and Mary, Virginia Dissertation Advisor: Nancy Condee, Professor, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright © by Olga Klimova 2013 iii SOVIET YOUTH FILMS UNDER BREZHNEV: WATCHING BETWEEN THE LINES Olga Klimova, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 The central argument of my dissertation emerges from the idea that genre cinema, exemplified by youth films, became a safe outlet for Soviet filmmakers’ creative energy during the period of so-called “developed socialism.” A growing interest in youth culture and cinema at the time was ignited by a need to express dissatisfaction with the political and social order in the country under the condition of intensified censorship. I analyze different visual and narrative strategies developed by the directors of youth cinema during the Brezhnev period as mechanisms for circumventing ideological control over cultural production. -

5. Calling for International Solidarity: Hanns Eisler’S Mass Songs in the Soviet Union

From Massenlieder to Massovaia Pesnia: Musical Exchanges between Communists and Socialists of Weimar Germany and the Early Soviet Union by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Supervisor ___________________________ Edna Andrews ___________________________ John Supko ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 i v ABSTRACT From Massenlieder to Massovaia Pesnia: Musical Exchanges between Communists and Socialists of Weimar Germany and the Early Soviet Union by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Supervisor ___________________________ Edna Andrews ___________________________ John Supko ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 Copyright by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry 2014 Abstract Group songs with direct political messages rose to enormous popularity during the interwar period (1918-1939), particularly in recently-defeated Germany and in the newly- established Soviet Union. This dissertation explores the musical relationship between these two troubled countries and aims to explain the similarities and differences in their approaches to collective singing. The discussion of the very complex and problematic relationship between the German left and the Soviet government sets the framework for the analysis of music. Beginning in late 1920s, as a result of Stalin’s abandonment of the international revolutionary cause, the divergences between the policies of the Soviet government and utopian aims of the German communist party can be traced in the musical propaganda of both countries.