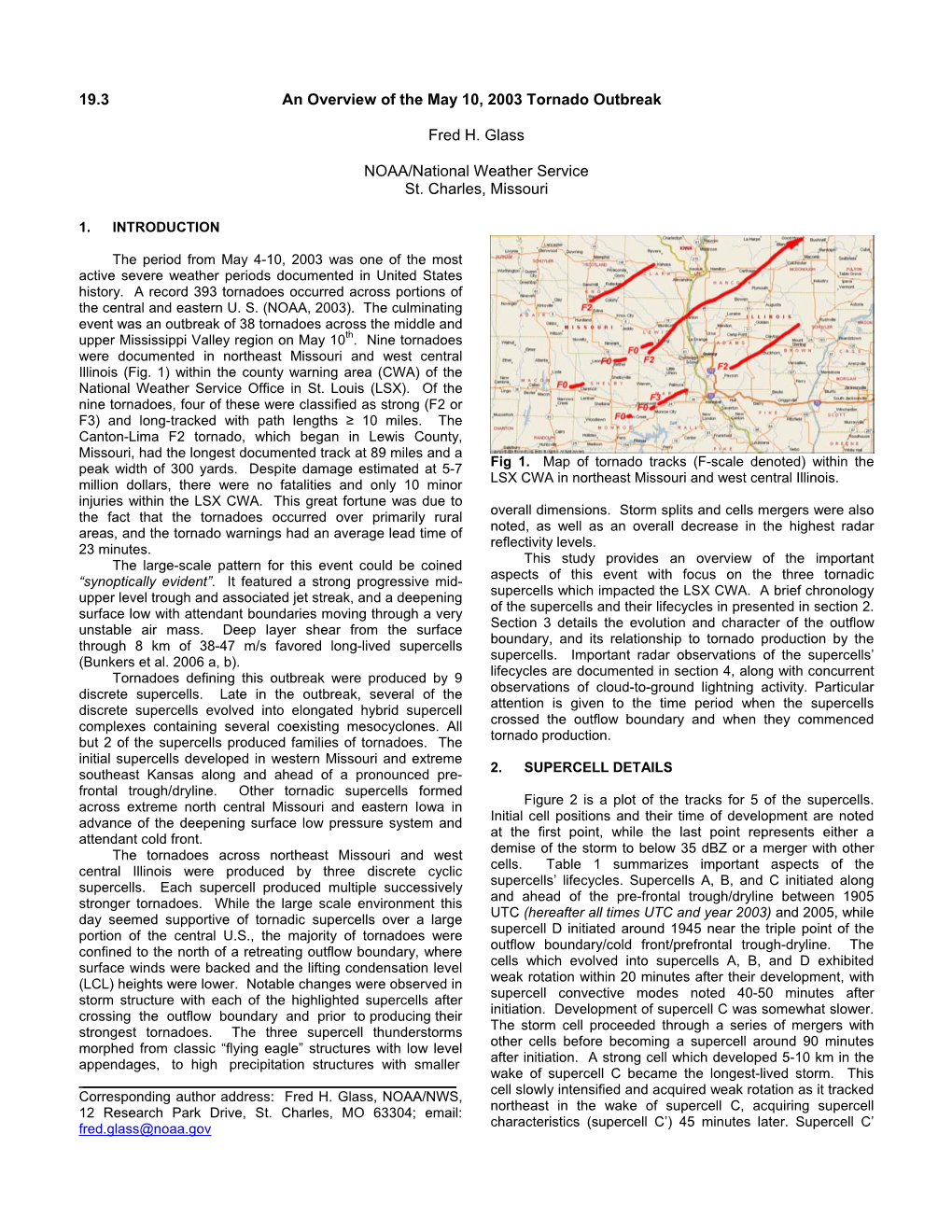

19.3 an Overview of the May 10, 2003 Tornado Outbreak Fred H. Glass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developing a Tornado Emergency Plan for Schools in Michigan

A GUIDE TO DEVELOPING A TORNADO EMERGENCY PLAN FOR SCHOOLS Also includes information for Instruction of Tornado Safety The Michigan Committee for Severe Weather Awareness March 1999 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS: A GUIDE TO DEVELOPING A TORNADO EMERGENCY PLAN FOR SCHOOLS IN MICHIGAN I. INTRODUCTION. A. Purpose of Guide. B. Who will Develop Your Plan? II. Understanding the Danger: Why an Emergency Plan is Needed. A. Tornadoes. B. Conclusions. III. Designing Your Plan. A. How to Receive Emergency Weather Information B. How will the School Administration Alert Teachers and Students to Take Action? C. Tornado and High Wind Safety Zones in Your School. D. When to Activate Your Plan and When it is Safe to Return to Normal Activities. E. When to Hold Departure of School Buses. F. School Bus Actions. G. Safety during Athletic Events H. Need for Periodic Drills and Tornado Safety Instruction. IV. Tornado Spotting. A. Some Basic Tornado Spotting Techniques. APPENDICES - Reference Materials. A. National Weather Service Products (What to listen for). B. Glossary of Weather Terms. C. General Tornado Safety. D. NWS Contacts and NOAA Weather Radio Coverage and Frequencies. E. State Emergency Management Contact for Michigan F. The Michigan Committee for Severe Weather Awareness Members G. Tornado Safety Checklist. H. Acknowledgments 2 I. INTRODUCTION A. Purpose of guide The purpose of this guide is to help school administrators and teachers design a tornado emergency plan for their school. While not every possible situation is covered by the guide, it will provide enough information to serve as a starting point and a general outline of actions to take. -

A Climatology and Comparison of Parameters for Significant Tornado

106 WEATHER AND FORECASTING VOLUME 27 A Climatology and Comparison of Parameters for Significant Tornado Events in the United States JEREMY S. GRAMS AND RICHARD L. THOMPSON NOAA/NWS/Storm Prediction Center, Norman, Oklahoma DARREN V. SNIVELY Department of Geography, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio JAYSON A. PRENTICE Department of Geological and Atmospheric Sciences, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa GINA M. HODGES AND LARISSA J. REAMES School of Meteorology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma (Manuscript received 18 January 2011, in final form 30 August 2011) ABSTRACT A sample of 448 significant tornado events was collected, representing a population of 1072 individual tornadoes across the contiguous United States from 2000 to 2008. Classification of convective mode was assessed from radar mosaics for each event with the majority classified as discrete cells compared to quasi- linear convective systems and clusters. These events were further stratified by season and region and com- pared with a null-tornado database of 911 significant hail and wind events that occurred without nearby tornadoes. These comparisons involved 1) environmental variables that have been used through the past 25– 50 yr as part of the approach to tornado forecasting, 2) recent sounding-based parameter evaluations, and 3) convective mode. The results show that composite and kinematic parameters (whether at standard pressure levels or sounding derived), along with convective mode, provide greater discrimination than thermodynamic parameters between significant tornado versus either significant hail or wind events that occurred in the absence of nearby tornadoes. 1. Introduction severe thunderstorms and tornadoes (e.g., Bluestein 1999; Davies-Jones et al. 2001; Wilhelmson and Wicker Severe weather forecasting has evolved considerably 2001). -

An Observational Analysis Quantifying the Distance of Supercell-Boundary Interactions in the Great Plains

Magee, K. M., and C. E. Davenport, 2020: An observational analysis quantifying the distance of supercell-boundary interactions in the Great Plains. J. Operational Meteor., 8 (2), 15-38, doi: https://doi.org/10.15191/nwajom.2020.0802 An Observational Analysis Quantifying the Distance of Supercell-Boundary Interactions in the Great Plains KATHLEEN M. MAGEE National Weather Service Huntsville, Huntsville, AL CASEY E. DAVENPORT University of North Carolina at Charlotte, Charlotte, NC (Manuscript received 11 June 2019; review completed 7 October 2019) ABSTRACT Several case studies and numerical simulations have hypothesized that baroclinic boundaries provide enhanced horizontal and vertical vorticity, wind shear, helicity, and moisture that induce stronger updrafts, higher reflectivity, and stronger low-level rotation in supercells. However, the distance at which a surface boundary will provide such enhancement is less well-defined. Previous studies have identified enhancement at distances ranging from 10 km to 200 km, and only focused on tornado production and intensity, rather than all forms of severe weather. To better aid short-term forecasts, the observed distances at which supercells produce severe weather in proximity to a boundary needs to be assessed. In this study, the distance between a large number of observed supercells and nearby surface boundaries (including warm fronts, stationary fronts, and outflow boundaries) is measured throughout the lifetime of each storm; the distance at which associated reports of large hail and tornadoes occur is also collected. Statistical analyses assess the sensitivity of report distributions to report type, boundary type, boundary strength, angle of interaction, and direction of storm motion relative to the boundary. -

PRC.15.1.1 a Publication of AXA XL Risk Consulting

Property Risk Consulting Guidelines PRC.15.1.1 A Publication of AXA XL Risk Consulting WINDSTORMS INTRODUCTION A variety of windstorms occur throughout the world on a frequent basis. Although most winds are related to exchanges of energy (heat) between different air masses, there are a number of weather mechanisms that are involved in wind generation. These depend on latitude, altitude, topography and other factors. The different mechanisms produce windstorms with various characteristics. Some affect wide geographical areas, while others are local in nature. Some storms produce cooling effects, whereas others rapidly increase the ambient temperatures in affected areas. Tropical cyclones born over the oceans, tornadoes in the mid-west and the Santa Ana winds of Southern California are examples of widely different windstorms. The following is a short description of some of the more prevalent wind phenomena. A glossary of terms associated with windstorms is provided in PRC.15.1.1.A. The Beaufort Wind Scale, the Saffir/Simpson Hurricane Scale, the Australian Bureau of Meteorology Cyclone Severity Scale and the Fugita Tornado Scale are also provided in PRC.15.1.1.A. Types Of Windstorms Local Windstorms A variety of wind conditions are brought about by local factors, some of which can generate relatively high wind conditions. While they do not have the extreme high winds of tropical cyclones and tornadoes, they can cause considerable property damage. Many of these local conditions tend to be seasonal. Cold weather storms along the East coast are known as Nor’easters or Northeasters. While their winds are usually less than hurricane velocity, they may create as much or more damage. -

Mechanisms for Organization and Echo Training in a Flash-Flood-Producing Mesoscale Convective System

1058 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW VOLUME 143 Mechanisms for Organization and Echo Training in a Flash-Flood-Producing Mesoscale Convective System JOHN M. PETERS AND RUSS S. SCHUMACHER Department of Atmospheric Science, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado (Manuscript received 19 February 2014, in final form 18 December 2014) ABSTRACT In this research, a numerical simulation of an observed training line/adjoining stratiform (TL/AS)-type mesoscale convective system (MCS) was used to investigate processes leading to upwind propagation of convection and quasi-stationary behavior. The studied event produced damaging flash flooding near Dubuque, Iowa, on the morning of 28 July 2011. The simulated convective system well emulated characteristics of the observed system and produced comparable rainfall totals. In the simulation, there were two cold pool–driven convective surges that exited the region where heavy rainfall was produced. Low-level unstable flow, which was initially convectively in- hibited, overrode the surface cold pool subsequent to these convective surges, was gradually lifted to the point of saturation, and reignited deep convection. Mechanisms for upstream lifting included persistent large-scale warm air advection, displacement of parcels over the surface cold pool, and an upstream mesolow that formed between 0500 and 1000 UTC. Convection tended to propagate with the movement of the southeast portion of the outflow boundary, but did not propagate with the southwest outflow boundary. This was explained by the vertical wind shear profile over the depth of the cold pool being favorable (unfavorable) for initiation of new convection along the southeast (southwest) cold pool flank. A combination of a southward-oriented pressure gradient force in the cold pool and upward transport of opposing southerly flow away from the boundary layer moved the outflow boundary southward. -

George C. Mdrrhall Space Flight Center Marshall Space F/@T Center, Alabdrnd

NASA TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM (NASA-TU-78262) A PRELI8INABY LOOK AT N80- 18636 AVE-SESAHE 1 CONDUCTED 0U 10-11 APRIL 1979 (8lASA) 52 p HC AO4/HP A01 CSCL 040 Unclas G3/47 47335 A PRELIMINARY LOOK AT AVE-SESAME I CONDUCTED ON APRIL 10-1 1, 1979 By Steven F. Williams, James R. Scoggins, Nicholas Horvath, and Kelly Hill February 1980 NASA George C. Mdrrhall Space Flight Center Marshall Space F/@t Center, Alabdrnd MBFC - Form 3190 (Rev June 1971) ,. .. .. .. , . YAFrl," I?? CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES ........................... iv LIST OF TABLES ............................ vii 1. OBJECTIVES AND SCOPE ...................... 1 2. DATA COLLECTGD ......................... 1 a. Rawinsonde Soundinps.... .................... 1 b. Surface a* Upper -Air -..+ .................... 4 3. SMOPTIC CONDITIONS ....................... 4 a. Synoptic Charts ....................... 4 b. Radar.. .......................... 5 c. Satellite.. ........................ 5 4. SEVERE AND UNUSUAL WkXPIk h. REPORTED ............... 37 PRriCICDINQ PAGE BUNK NOT FKMED iii - .%; . ,,. r* , . * *. '' ,..'~ LIST OE' FIGURES Figure Page Location of rawinsonde stations participating in the AVE-SESAME I experiment ................. 3 Synoptic charts for 1200 GMT. 10 April 1979 ....... 6 Surface chart for 1800 GMT. 10 April 1979 ........ 9 Synoptic charts for 0000 GMT. 11 April 1979 ....... 10 Surface chart for 0600 GMT. 11 April 1979 ........ 13 Synoptic charts for 1200 GMT. 11 April 1979 ....... 14 Radar sunmxy for 1435 GMT. 10 April 1979 ........ 17 Radar summary for 1935 GMT. 10 ~pril1979 ........ 17 Radar summary for 2235 GMT. 10 April1979 ........ 18 Radar sumnary for 0135 GMT. 11 ~pril1979 ........ 18 Radar summary for 0235 GMT. 11 ~pril1979 ........ 19 Radar sununary for 0435 GMT. 11 April 1979 ........ 19 Radar summary for 0535 GMT. 11 April 1979 ....... -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

A Targeted Modeling Study of the Interaction Between a Supercell and a Preexisting Airmass Boundary

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations & Theses in Earth and Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department Atmospheric Sciences of 5-2010 A Targeted Modeling Study of the Interaction Between a Supercell and a Preexisting Airmass Boundary Jennifer M. Laflin University of Nebraska at Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geoscidiss Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Laflin, Jennifer M., "A Targeted Modeling Study of the Interaction Between a Supercell and a Preexisting Airmass Boundary" (2010). Dissertations & Theses in Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. 6. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geoscidiss/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations & Theses in Earth and Atmospheric Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A TARGETED MODELING STUDY OF THE INTERACTION BETWEEN A SUPERCELL AND A PREEXISTING AIRMASS BOUNDARY by Jennifer M. Laflin A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree Master of Science Major: Geosciences Under the Supervision of Professor Adam L. Houston Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2010 A TARGETED MODELING STUDY OF THE INTERACTION BETWEEN A SUPERCELL AND A PREEXISTING AIRMASS BOUNDARY Jennifer Meghan Laflin, M. S. University of Nebraska, 2010 Adviser: Adam L. Houston It is theorized that supercell thunderstorms account for the majority of significantly severe convective weather which occurs in the United States, and as a result, it is necessary that the mechanisms which tend to produce supercells are recognized and investigated. -

Table of Contents

The Nineties in America Table of Contents A Abortion Academy Awards Advertising Africa and the United States African Americans Agassi, Andre Agriculture in Canada Agriculture in the United States AIDS epidemic Air pollution Airline industry Albee, Edward Albert, Marv Albright, Madeleine Allen, Woody Ally McBeal Alternative rock Alvarez, Julia Alzheimer's disease Amazon.com America Online Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 AmeriCorps Angelou, Maya Angels in America Antidepressants Apple Computer Archaeology Archer Daniels Midland scandal Architecture Armey, Dick Armstrong, Lance Arnett, Peter Art movements Asian Americans Astronomy Attention-deficit disorder Audiobooks Autism Auto racing Automobile industry B Bailey, Donovan Baker, James Baker v. Vermont Balanced Budget Act of 1997 Ballet Bank mergers Barkley, Charles Barry, Dave Barry, Marion Baseball Baseball realignment Baseball strike of 1994 Basic Instinct Basketball Baywatch Beanie Babies Beauty and the Beast Beauty Myth, The Beavis and Butt-Head Bernadin, Joseph Cardinal Beverly Hills, 90210 Bezos, Jeff Biosphere 2 Blair, Bonnie Blair Witch Project, The Blended families Bloc Québécois Blogs Bobbitt mutilation case Bondar, Roberta Bono, Sonny Book clubs Bosnia conflict Bowl Championship Series (BCS) Boxing Boy bands Broadway musicals Brooks, Garth Brown, Ron Browning, Kurt Buchanan, Pat Buffett, Warren Burning Man festivals Bush, George H. W. Business and the economy in Canada Business and the economy in the United States Byrd murder case C Cable television Cammermeyer, Margarethe -

Multiscale Overview of a Violent Tornado Outbreak with Attendant Flash Flooding

416 WEATHER AND FORECASTING VOLUME 15 Multiscale Overview of a Violent Tornado Outbreak with Attendant Flash Flooding JOSEPH A. ROGASH NOAA/NWS/Storm Prediction Center, Norman, Oklahoma RICHARD D. SMITH National Weather Service, Tulsa, Oklahoma (Manuscript received 8 January 1999, in ®nal form 7 January 2000) ABSTRACT On 1 March 1997 violent tornadoes caused numerous fatalities and widespread damage across portions of central and eastern Arkansas and western Tennessee. In addition, the associated thunderstorms produced very heavy rainfall and ¯ash ¯ooding, with a few locations receiving up to 150 mm (6 in.) of rainfall in 3 h. The initial environment appeared favorable for strong tornadoes with unseasonably warm moist air at lower levels resulting in signi®cant instability (convective available potential energy values between 1400 and 1800 J kg21) where 0±2-km storm-relative helicities exceeded 300 m2 s22 and the middle-tropospheric storm-relative ¯ow was conducive for tornadic supercells. The most destructive tornadoes developed along a preexisting surface boundary where lower-tropospheric moisture convergence and frontogenesis were enhanced. Tornadoes and heaviest rainfall only ensue after upward motion associated with the direct circulation of an upper-tropospheric jet streak became collocated with lower-tropospheric upward forcing along the surface boundaries. From a ¯ash ¯ood perspective the event occurred in a hybrid mesohigh-synoptic heavy rain pattern as thunderstorms developed and moved along surface boundaries aligned nearly parallel to the mean wind. In addition, strong ¯ow and associated moisture ¯ux convergence in the lower troposphere favored the formation of cells to the southwest or upstream of the initial convection with thunderstorms, including a a tornadic supercell, traversing over the same area. -

Another Look at the 11 April 1965 Palm Sunday Outbreak

Central Region Technical Attachment Number 15-02 December 2015 Another Look at the 11 April 1965 Palm Sunday Outbreak JON CHAMBERLAIN National Weather Service, Rapid City, South Dakota ABSTRACT The 11 April 1965 tornado outbreak was one of the most devastating tornado outbreaks in recorded history, affecting six Midwestern states with significant loss of life and property. This storm system was particularly interesting for the number of discrete tornadic supercells in the southern Great Lakes, especially given the number of F3+ tornadoes. In addition, many supercells were observed to contain multiple funnels and multiple tornado cyclones (some occurring simultaneously). Dr. Theodore Fujita performed a comprehensive analysis of this event in the late 1960s, featuring a detailed analysis of both the meteorology and tornado damage paths. However, technology and science have progressed much between 1970 and 2015, with new forecast parameters and techniques available to forecasters. The Palm Sunday Outbreak of 1965 was re-examined using modern-day severe weather forecast parameters derived from observational data to help understand why this storm system produced such violent thunderstorms, particularly across extreme northern Indiana. In order to do this, approximately 200 handwritten surface observations were obtained from the National Climatic Data Center’s Electronic Digital Archive Data System web interface. Once these observations were put into a database, several surface weather maps, synthetic soundings, hodographs, and upper-level analyses were constructed. These data, along with archived upper-air data, were used to calculate several severe weather forecast parameters, which truly revealed the magnitude of the event. 1. Introduction The 11 April 1965 tornado outbreak was one of the most devastating tornado outbreaks in recorded history. -

PRELUDE at 4:30 A.M. on June 29, I Began My Day with a Quick Look at the Weather Charts and Prepared to Make a Forecast. It

PRELUDE At 4:30 a.m. on June 29, I began my day with a quick look at the weather charts and prepared to make a forecast. It was to be yet another hot day across the region; you did not need a meteorologist to tell you that it would be hot because, you could feel already it before the sun ever rose. The morning air was thick, heavy and the winds offered no relief, they merely stirred the soupy air in the kettle of the Great Lakes. I knew that thunderstorms were expected that day, I had been eyeing a system on the charts for the past three days, and it was to arrive during the late afternoon across the region I forecasted for (Cleveland, Ohio; Erie, Pennsylvania; Fort Wayne, Indiana; and Toledo, Ohio). I remember vividly making the comment “You’re going to need a big [weather] event to push this heat back” on my website’s morning forecast update. Little was I prepared that the event would be a derecho – an event that squall-line lovers, like myself, adore. Lucille was returning from Chicago, Illinois on her way back to Lima, Ohio, so I had to watch the weather of northern Indiana since I was expecting thunderstorms. I was located in Bowling Green, Ohio – a town which is no stranger to straight line winds from the squall lines that inhabit our world in the summer time. To our south was the city of Findlay, Ohio, where Kelly and her church were located near the downtown region, a city where their biggest weather event was the semi-decadal floods that occur along the banks of the Blanchard River.