Final Report CXB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PETRRA - an Experiment BOOK: 6/10 in Pro-Poor Communication - Agricultural Getting Messages to Stakeholders Research

es ADESH erienc ANGL xp B t, ojec A pr earning and e L ETRR of the P PETRRA - an experiment BOOK: 6/10 in pro-poor Communication - agricultural getting messages to stakeholders research Edited by Noel P. Magor, Ahmad Salahuddin, Mamunul Haque, Tapash K. Biswas and Matt Bannerman Poverty Elimination Through Rice Research Assistance (PETRRA), 1999-2004 a project funded by DFID, managed by IRRI in close collaboration with BRRI Book 6. Communication - getting messages to stakeholders Communication brief no. 6 Communication - getting messages to stakeholders Alastair Orr, Fatima Jahan ASe.e Smaal,a Shuhdadilian ,A Mrif.a HNaaqbuie, Jaankdi rNulo eIls lPa.m M Paegteorr INTRODUCTION section. There was a broad two-pronged approach: Communication or getting messages to stakeholders grew in importance over the targeting the government (GO) and life of Poverty Elimination Through Rice non-governmental organisation (NGO) Research Assistance (PETRRA) project; policy makers, donors, research to the point that it was given output-level managers, scientists, and extension status on the logical framework. In other managers; and words it was essential for PETRRA to targeting the end-users of the achieve its purpose-level objectives. innovations, namely, farmers and GO- It could be asked why has communication NGO extension workers. become so important? Public-funded research is for improving the livelihoods of poor households and there has been a THE MAIN MESSAGES growing demand for accountability in delivering impact from that research. At PETRRA SPs can be divided into three one level, the agricultural research categories and each category had its own community has neglected to communicate message to communicate to its audience: its importance in the fight to reduce Category 1: Technology identification, poverty. -

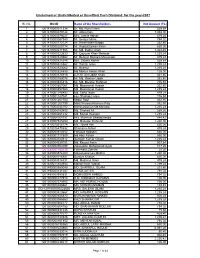

List of Unclaimed Dividend

Unclaimed or Undistributed or Unsettled Cash Dividend for the year-2007 Sl. No. BO ID Name of the Shareholders Net Amount (Tk.) 1 1201470000011334 Dr. Md. Nurul Islam 529.64 2 1201470000079144 Mr. Alaka Das. 7,938.00 3 1201470000079227 Mrs. Jamila Akhter. 479.24 4 1201470000087340 Mr. Serajul Islam. 794.02 5 1201470000173124 Mr. Imran Islam Bappy 352.80 6 1201470000200174 Mr. Asaduzzaman Khan 630.00 7 1201470000271905 Mr. Md. Badrul Alam 1,424.46 8 1201470000323639 Mr. Qayyum Khan Mahbub 1,235.24 9 1201470000329462 Mr. Belayet Hossain Mozumder 479.24 10 1201470000428346 Mrs. Sabina Akther 529.64 11 1201470000428362 Mr. Tanzin Islam 1,235.24 12 1201470000520062 Mr. Ikramul 1,235.24 13 1201470000524459 Md Mokter Hosan Khan 126.00 14 1201470000574918 G.H.M. Arif Uddin Khan 441.66 15 1201470000769078 Mr. Md. Iftekher Uddin 352.80 16 1201470000845416 Mr. Md. Mizanur Rahman 705.60 17 1201470000857067 Md. Mozammel Husain 352.80 18 1201470000857083 Md. Mozammel Husain 1,235.24 19 1201470001146492 Md. Saiful Islam 479.24 20 1201470001147041 kazi Shahidul Islam 176.84 21 1201470001207780 Abdur Rouf 352.80 22 1201470001207799 Most Waresa Khanam Prity 352.80 23 1201470004044792 Moniruzzaman Md.Mostafa 1,235.24 24 1201470004193803 Md. Shahed Ali 265.26 25 1201470004261632 Md. Kamal Hossain 1,235.24 26 1201470004708797 Mrs. Munmun Bhattacharjee 844.42 27 1201470007925659 Md. Masudur Rahman 1,260.00 28 1201470010616174 Ms. Hosna Ara 630.00 29 1201470016475332 Shamima Akhter 479.24 30 1201480000970352 Faruque Hossain 630.00 31 1201480001717909 Md Abul Kalam 630.00 32 1201480003543312 Santosh Kumar Ghosh 1,235.24 33 1201480004339151 Md. -

Forests and the Biodiversity Convention Independent Monitoring of the Implementation of the Expanded Programme of Work in Bangladesh

Forests and the Biodiversity Convention Independent Monitoring of the Implementation of the Expanded Programme of Work in Bangladesh Wildlife Trust of Bangladesh GFC coordinator for the Independent monitoring programme: Miguel Lovera Global Forest Coalition Bruselas 2273 Asunción, Paraguay E-mail: [email protected] Citation: Country monitoring report on Bangladesh. (2008) 27 pages. Independent monitoring of the implementation of the Expanded Work Programme on forest biodiversity of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD POW), 2002-2007. Wildlife Trust of Bangladesh. By: 1 2,3 1 4 Sabir Bin Muzaffar , M. Anwarul Islam , Dihider Shahriar Kabir , Mamunul Hoque Khan , Farid Uddin Ahmed 5, Gawsia Wahidunnessa Chowdhury 3,6 , Suprio Chakma 3, Israt Jahan 3 1. School of Environmental Science and Management, Independent University, Bangladesh (IUB) 2. Department of Zoology, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh 3. Wildlife Trust Bangladesh 4. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Dhaka, Bangladesh 5. Arannayk Foundation, Dhaka, Bangladesh 6. Department of Fisheries and Marine Science, Noakhali Science and Technology University, Bangladesh Disclaimer: The information contained in this report has been provided by the independent country monitor. As such, the report does not necessarily reflect the opinion or position of GFC or other contributors. Cover: Kaptai National Park, a semi evergreen forest in the southeast. Photographer: Gawsia W. Chowdhury . This report was made possible through the generous contribution of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. For more information visit: www.globalforestcoalition.org © Global Forest Coalition, May 2008 2 Global Forest Coalition EXECUTIVE SUMMARY An independent assessment was conducted on the implementation status of the Programme of Work of the Convention on Biological Diversity in Bangladesh. -

The Viral Frontline Bangladesh Country Report

TRUTH IN A TIME OF CONTAGION: THE VIRAL FRONTLINE BANGLADESH COUNTRY REPORT 19TH ANNUAL SOUTH ASIA PRESS FREEDOM REPORT 2020-21 2 incarceration. The writer was allegedly tortured in custody and his family members described the death as BANGLADESH mysterious. His 'crime' was to question the government about the handling of the Covid-19 pandemic. NOT COWED DOWN DESPITE The only good news in this bleak period was the recovery on 1 November of journalist Golam EXTREMISM AND DIGITAL ONSLAUGHT Sarwar, who went missing on 29 October. He was The Covid-19 pandemic that gripped the region in 2020, found unconscious near a canal at Sitakunda of became a pretext for an authoritarian crackdown in Southern Chattogram district. He was heavily bruised, Bangladesh, which saw a series of arrests of journalists, stripped off his clothes, but thankfully, alive. censorship and targeting of critics of the government. Harassment, intimidation and the targeted killing of ARRESTS AND CASES UNDER DSA three journalists were grim reminders of the dangers The government cracked down on free speech during faced by Bangladeshi journalists in the line of duty. The the pandemic, and regularly dissenting voices were death of a writer in police custody detained under the silenced by the draconian Digital Security Act. Digital Security Act once more shone the spotlight on The lone Cyber Crimes Tribunal in Dhaka launched in this draconian law that institutes heavy penalties with 2013, with the entire country under its jurisdiction, has little due process protections for perceived violations. It 3,324 cases pending, most of which are filed due to Facebook is a serious curb on freedom of expression online. -

Three-Month Human Rights Monitoring Report on Bangladesh

THREE-MONTH HUMAN RIGHTS MONITORING REPORT ON BANGLADESH Reporting Period: January – March 2021 Prepared by Odhikar Date of Release: 8 April 2021 Foreword Since its inception in 1994, Odhikar has been relentlessly struggling to protect the civil, political, social, economic and cultural rights of the people. Odhikar, as an organisation of human rights defenders, has always sought to raise awareness of all human rights violations committed by the state and campaign for internationally recognized civil and political rights, to protest and prevent the state from violating human rights. Odhikar unconditionally stands by the victims of human rights violations and works to ensure the safety of the victims and establish justice. Odhikar has been facing extreme state repression and harassment since 2013 while working to protect human rights. Despite this adverse situation, Odhikar has prepared a human rights report for the first three months of 2021 based on the reports sent by the human rights defenders associated with it and with the help of data published in various media. To see the previous human rights reports of Odhikar, please visit www.odhikar.org; Facebook: Odhikar.HumanRights; Twitter: @odhikar_bd 2 Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Statistics: Human Rights violations (January-March) 2021 ........................................................................... 7 Violation of Freedom -

Electronic Subscription System Allotment Detail Report South Bangla Agriculture & Commerce Bank Limited

Electronic Subscription System Allotment Detail Report South Bangla Agriculture & Commerce Bank Limited Name of TREC Holder/MB Apex Investments Limited(DSE-007) DP ID 20200 Trading App Alloted Alloted Refund DP ID Applicant Name BOID App Qty Code Amount Qty Amount Amount ASI 20200 00489 MRS. SHAHANARA 1202020000048544 1,000 10,000 77 770 9230 BEGUM 20200 09997 MR.SUBHASH CHANDRA 1202020003031722 5,000 50,000 382 3,820 46180 DAS 20200 11732 SALIM ULLAH MOZUMDER 1202020003878071 3,000 30,000 229 2,290 27710 20200 11733 SALIM ULLAH MOZUMDER 1202020003878096 3,000 30,000 228 2,280 27720 20200 10441 MUKTA MAJUMDER 1202020003878872 1,000 10,000 76 760 9240 20200 16441 M.M.NAZMUZZAMAN 1202020005679731 5,000 50,000 381 3,810 46190 (JEWEL) 20200 16449 MD NADIM UL KARIM 1202020005679584 2,000 20,000 152 1,520 18480 KHAN 20200 16442 M.M.NAZMUZZAMAN 1202020005679822 5,000 50,000 381 3,810 46190 (JEWEL) 20200 21706 SHIPRA SARKAR 1202020006939743 1,000 10,000 76 760 9240 20200 21733 PARASA BEGUM 1202020007030345 2,000 20,000 153 1,530 18470 20200 21734 PARSHA BEGUM 1202020007030361 2,000 20,000 153 1,530 18470 20200 26509 LUTFOR RAHMAN RIPON 1202020008600339 1,000 10,000 77 770 9230 20200 26510 LUTFOR RAHMAN RIPON 1202020008600347 1,000 10,000 77 770 9230 20200 10559 MD MASUD RANA 1202020006874125 1,000 10,000 77 770 9230 20200 16132 MD.ZAHIRUL ISLAM 1202020005562316 2,000 20,000 152 1,520 18480 20200 16133 FARIDUDDIN AHMED 1202020005562937 2,000 20,000 152 1,520 18480 20200 16135 ASMA AHMED 1202020005562971 2,000 20,000 153 1,530 18470 20200 16136 ASMA AHMED 1202020005576057 1,000 10,000 77 770 9230 20200 16137 MOLINA BEGUM 1202020005576065 2,000 20,000 153 1,530 18470 20200 21788 ETI ISLAM 1202020006949501 1,000 10,000 76 760 9240 20200 21794 RONY FRANCIS GOMES 1202020006970586 2,000 20,000 153 1,530 18470 20200 21797 REBECA FOLIA 1202020006970709 1,000 10,000 76 760 9240 20200 09672 MR.MD.AMINU ISLAM 1202020003242119 5,000 50,000 381 3,810 46190 KUHEL 20200 09976 MR. -

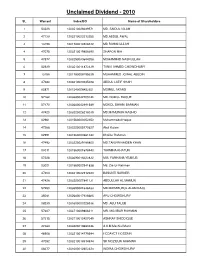

Unclaimed Divident

Unclaimed Dividend - 2010 SL Warrant Index/BO Name of Shareholders 1 53228 1203510028389571 MD. SAIDUL ISLAM 2 47139 1203210023213255 MD.ABDUL AWAL 3 13198 1201780014506732 MD RAHIM ULLAH 4 47075 1203210019858390 SHAPON MIA 5 47877 1203250030694258 MOHAMMAD NASRULLAH 6 52939 1203510011873339 TANIA AHMED CHOWDHURY 7 13158 1201780008195339 MUHAMMED JOINAL ABEDIN 8 47083 1203210020245028 ABDUL LATIF SHAH 9 02871 1201540028453351 MOINUL AKAND 10 57162 1203680042709146 MD. NURUL HAQUE 11 57170 1203680042991549 MOKOL BIHARI BARMAN 12 47420 1203220026218039 MD.MAMUNUR RASHID 13 02961 1201560000052453 Muhammadul Haque 14 47268 1203220005770627 Abul Kalam 15 02991 1201560000661043 Khalilur Rahman 16 47493 1203220039188800 MD.TANVIR HAIDER KHAN 17 03011 1201560001678440 TAKMINA KHATUN 18 57226 1203690018323832 MIS. FARHANA YEAKUB 19 03021 1201560002941838 Md. Zia-Ur-Rahman 20 47204 1203210032912220 BASUNTI SARKER 21 47428 1203220027841131 ABDULLAH AL MAMUN 22 57250 1203690021646433 MD.MAHABUBUL ALAM RAJU 23 35081 1202680017936686 APU CHOWDHURY 24 08239 1201600000226936 MD. ABU TALEB 25 57307 1203710009806211 MR. MOJIBUR RAHMAN 26 57315 1203710012427049 ASHRAF SHIDDIQUE 27 47364 1203220018680346 A.K.M Mashiul Munir 28 46908 1203210014779544 HEDAYET HOSSAIN 29 47052 1203210018914874 SK MOZIBUR RAHMAN 30 08377 1201600012603324 INDIRA CHOWDHURY SL Warrant Index/BO Name of Shareholders 31 57331 1203710015964211 MD. ZAHIRUL ALAM 32 47228 1203210037641713 MD.MAHMUDUL ALAM SIDDIQUE 33 08429 1201600014872934 SHIRIN AKTHER 34 35212 1202680041829803 RUMA -

Rolling Mills Limited

Bangladesh Steel Re- Rolling Mills Limited Summary of Unclaimed Dividend (From year2014- to Year 2016-17) Year Amount (BDT) 2014 832,953 2015 36,618 2016-17 734,943 Others/Unspecified 146,346 Grand Total 1,750,860 Bangladesh Steel Re- Rolling Mills Limited Unclaimed dividend for the year 2014 BO A/C No/ Folio Name of Shareholder/Unit SL Father Name Mother Name Address Amount (BDT) Number Holder 1 1202390042715691 MST. REZINA PARVIN MD. RAZAUL KARIM ROWSHAN ARA KHANAMC/O: MD. REZAUL KARIM,NAVAL STORES DEPOT,CTG.CTG4218 170.00 2 1202490025904682 ANOWARUL ISLAM LATE ABDUL SAMAD FATIMA BEGUM CHIKDAIR, ANWARNA BAZI, RAWJANCTG3915 170.00 3 1202490026907934 YASIN MIAH MOSTAFIZUR RAHMAN LATE MAZEDA KHATUN SOUTH OLI NAGAR, KNERHATMIRSARAICTG3910 170.00 4 1202800041830951 ABDUR RAZZAK KABIR AHMED ZABUN ARA VILL+PO- NOAPARAPS- RAOZANCHITTAGONG4300 170.00 5 1202840056739328 NURUL HOQUE ALI NOWAZ MAMONA BEGUM 596/B JAWTALA RAILWAYCOLONY,PHARTALI,CHITTAGONG4204 170.00 6 1202930033479104 DULAL MIAH LATE MOTILAL KANAKCAPA WEST SHILAK. SHILAK. RONGUNIACHITTAGONGCHITAGONG00 170.00 7 1202930040296831 SAMAD HOSSAIN NAZIR HOSSAIN SHAHURA KHATUN NAITTANGPARA, TEKNAF SADARTEKNAF, COX'S BAZARCOX'SBAZARX 170.00 8 1202930041054971 MIZANUR RAHAMAN KAMAL RAHAMAN GUL SEHER BEGUM RINGVONG SAGIRSHAHKATA,MULU-MGHAT CHAKARIA, COX'SBAZARCOX'SBAZARX 170.00 9 1202930047561070 MOHAMMED USMAN LAL MIAH HALIMA KATUN UTTOR PARA, SHAHAPARIRDWIPTEKNAF, COX`S BAZARCOX`S BAZAR. 170.00 10 1203210007257943 MOHAMMED SAIFUDDIN LATE AMIRHAMZA SHAFURA KHATUN VILL-12, CHOWTO DAMSHA,KARIYANAGAR, SATKANIACTG0 170.00 11 1203330022668861 DILU-ARA BEGUM ABDUL RAHIM SHARIN AKTER D/3686, HOSSAN MONJIL,PATANIAGODA, CHANDGAONCHITTAGONG4212 102.00 12 1203330043108168 BIKASH DEY SUNIL DEY PROVA RANI DEY VILL: BAZALIA HEAD MASTERBARI, P.O-BAZALIAP.S- SATKANIA, CTGCHITTAGONG4388 170.00 13 1203330048575474 ABDUR RAHIM MD.SABUR SAMON ARA BEGUN C/O,DOVASHIR BARI.VIL+PO-BATTAPS-ANOWARA . -

Download File

Staying Tuned Radio Programming for Sustained Behaviour Change and Accountability in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh This is one of a series of case studies based on UNICEF-supported communication, community engagement and accountability activities as part of the larger humanitarian response to the Rohingya refugee crisis in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, from September 2017 to December 2019. Editing: Rain Barrel Communications – Saudamini Siegrist, Brigitte Stark-Merklein and Robert Cohen Design: Azad/Drik The opinions expressed in this case study are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policies or views of UNICEF. Extracts from this case study may be freely reproduced provided that due acknowledgement is given to the source and to UNICEF. © United Nations Children’s Fund, July 2020 This is one of a series of case studies based on UNICEF-supported communication, community engagement ThUNICEFis is one Ba ngladesof a seriesh of case studies based on UNICEF-supported communication, community engagement andBSL accountOffice Complability exactivities, 1 Minto as R partoad of the larger humanitarian response to the Rohingya refugee crisis in Coandx ’saccount Bazar, abiliBangladesh,ty activities from as Septemberpart of the larger 2017 tohumani Decembertarian 2response019. to the Rohingya refugee crisis in CoDhakax’s B 10azar00,, BBangladesh,angladesh from September 2017 to December 2019. Author: Dr. Hakan Ergül 2 INFORMATION AND FEEDBACK CENTRES Editing: Rain Barrel Communications – Saudamini Siegrist, Brigitte Stark-Merklein and Robert Cohen Design:Editing: RainAzad/Drik Barrel Communications – Saudamini Siegrist, Brigitte Stark-Merklein and Robert Cohen Design: Azad/Drik The opinions expressed in this case study are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policies orThe vie opinionsws of UNICEF expressed. -

Berger Paints Limited

Berger Paints Bangladesh Limited List of Unclaimed/Unsettled IPO subscription money and Cash Dividend SL Year Folio/BO ID No Name Address Taka 1 IPO 2005 1202400003731404 SHEFALI BEGUM 159/2 UTTAR SATIR PARA RANGAMATIA 6,000 2 IPO 2005 1201690003844468 MD MOHI UDDIN KHA 1/5 BANK COLONY FARIDABAD 6,000 3 IPO 2005 1202250005242211 MD FAIJUR RAHMAN R R BHABAN 287 RASULPUR ROAD 6,000 4 IPO 2005 1301030001940039 SHAMSUN NAHAR BEGUM DHAKA BANK LTD. AGRABAD BRANCH 6,000 5 IPO 2005 1301030005913576 TANJINA HOQUE HOUSE NO 2335 CHARIAPARA PS-BANDAR 6,000 6 IPO 2005 1202990005757046 SYED SHARIFUL AKHTER 15/A SHAHEED MIRZA LANE YOUNUS VILLA 5TH FLOOR 6,000 7 IPO 2005 1202390005898185 MOHAMMED SHAH NEWAZ KABIR HOUSE 4,LANE-5 ROAD-1 BLOCK-L HALISHAHAR H/E 6,000 8 IPO 2005 1203230006067381 JASHIM UDDIN TALUKDER 438 MONSURABAD DT ROAD 6,000 9 IPO 2005 1202990005658668 JOY KANTI SARKAR AGRANI BANK BUILDING 4TH FLOOR 129 JUBILEE ROAD 6,000 10 IPO 2005 1201600003081745 MOHAMMED ILIAS 64 JOYNAGAR LANE-2 COLLAGE ROAD 6,000 11 IPO 2005 1301030005415486 MOHAMMED ISHAQUE BAKHTAIR MANSION HOUSE 48 ROAD 4 MOMINBAG 6,000 12 Final 2005 1201470000012636 MRS. KANIZ FATEMA DINA 30, Circuit House Road, 8,100 13 Final 2005 1201470000721941 MR. MD. KHALEQUEZZAMAN 89, Sabuj Bagh (1st Floor) 450 14 Final 2005 1201470000731920 MR. A.B.M. RAKIBUL BASET 104/F Central Road (G.F) 450 15 Final 2005 1201470001515672 SHANAJ SHAMMY 3/16 Humaun Road 450 16 Final 2005 1201470002847692 MAMUN CHOWDHURY House -26, Block -D, Road -11 450 17 Final 2005 1201470003192020 MD. -

Income Families and Taka 5000 to Each of Around One Lac Farmers

PRI]SS INFORMAl'ION DEPARl'MEN'f GOVERNMI]N'I OF BANGI-ADESI I DIIAKA Most Urgent Frorn: PlO, PID, Dhaka For: Bangladoot, Ail Missions I;ax:9540553/9540026 MSG.22612020-21 E-rnril: niddhakl0srnril.com Date: Monday, l9 April 2021 web: rvrlwffior bd News Brief A total of 36.25 lac poor families will get financial assistancd'$ git from Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina on the occasion of the upcoming Eid-ul-Fitr, Road Transport'adit Bridg6s Minister Obaidul Quader revealed this at a regular press conference -yesterday. As ,the continuation of d'if.fqtent rneasures taken by the government to ensure financial security of the distressed and vulnerable people who became jobless in the wake of coronavirus outbreak and due to lockdown,l.25 crore families will get food aid, he said. Turning to BNP's politics, he urged BNP Secretary General Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir to establish democracy inside the party at first before making different comments on the country's democracy. Earlier, the Minister virtually joining a review meeting of the Bridges Division on different development works informed that the progress of the Padma Bridge construction stood at 85 per cent till Saturday. The Minister further said, the progress of the Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Tunnel beneath the Karnaphuli river is 66.50 per cent so far. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasinawill provide Taka 2500 as financial aids to each of around 35 lac low- income families and Taka 5000 to each of around one lac farmers families, who became victims of coronavirus pandemic and natural disaster, PM's Press Secretary Ihsanul Karim said to media yesterday. -

Bangladesh College of Physicians and Surgeons (BCPS)

Bangladesh College of Physicians and Surgeons (BCPS) 67, Shaheed Tajuddin Ahmed Ave, Mohakhali, Dhaka, Bangladesh Registered Applicant list, FCPS Part-I Examination-July-2021. BMDC No Name Speciality 59768 SOBNOM SHIRMIN- Anaesthesiology 62449 ISRAT JAHAN - Anaesthesiology 63951 MD.ANAMUL HAQUE- Anaesthesiology 64277 FATEMA HOQUE- Anaesthesiology 65050 MD.SHAHEDUZZAMAN DEWAN- Anaesthesiology 66920 NAURIN AKTHER- Anaesthesiology 68420 ISRAT JAREEN HOQUE- Anaesthesiology 71947 MOHD. ALAUL ISLAM- Anaesthesiology A102564 TANMOY BHOWMIK - Anaesthesiology A102659 MD. HASIBUL HASAN- Anaesthesiology A27180 K.M. ABU MUSA- Anaesthesiology A29499 MD. SHAMIM KABIR SIDDQUE - Anaesthesiology A33697 MOHAMMED NAFEES ISLAM- Anaesthesiology A38885 SYADA MAHZABIN TAHER- Anaesthesiology A39013 MST. SHAHANAZ AKTER- Anaesthesiology A40310 MOHAMMAD MIZAN UDDIN EMRAN- Anaesthesiology A43996 MOHAMMED MAMUN MORSHED- Anaesthesiology A46053 MD. ABU BAKER SIDDIQUE- Anaesthesiology A46632 SUHANA FERDOUS- Anaesthesiology A47119 MOHD.SAIF HOSSAIN JOARDER- Anaesthesiology A47565 MD. GIAS KAMAL CHOWDHURY MASUM- Anaesthesiology A47733 MD. ABU RASEL BHUIYAN- Anaesthesiology A48289 S. M. NAZRUL ISLAM- Anaesthesiology A50441 NAZIR AHMED- Anaesthesiology A51261 MD. HASAN MAHMOOD- Anaesthesiology A55285 MUNMUN BARUA- Anaesthesiology A55588 MANSURA AKTER PANNA- Anaesthesiology A55825 ATAI RABBI- Anaesthesiology A56113 ANANNA MALLIK- Anaesthesiology A56329 KAMRUN NAHAR- Anaesthesiology A57179 DEWAN SABRINA MASUK- Anaesthesiology A57852 FARHANA KHANDOKER- Anaesthesiology A58914