Download Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JRA 29 1 Bookreview 190..192

Reviews of Books In , Deyell published his book Living Without Silver,3 which has become the definitive work on the monetary history of early medieval north India. In this new book, he has stretched back in time by a couple of centuries and has produced what is destined to become the definitive work on the coinage of that period. <[email protected]> PANKAJ TANDON Boston University MUSLIMS AGAINST THE MUSLIM LEAGUE:CRITIQUES OF THE IDEA OF PAKISTAN. Edited by ALI USMAN QASMI and MEGAN EATON ROBB. pp. vii, . Delhi, Cambridge University Press, . doi:./S One of the great developments of the last ten years of British rule in India was the transformation of the position of the All-India Muslim League. In the elections it won just five per cent of the Muslim vote; it could not be regarded as a serious political player. Yet, in the elections of – it won about per cent of the Muslim vote, winning out of seats in the central and provincial legislatures, a result which meant that the British and the Indian National Congress had to take seriously the League’s demand for the creation of Pakistan at independence, a demand which it had formally voiced in March . With the creation of Pakistan in , which was also the formation of the most populous Muslim nation in the world at the time, the narrative of how some Muslims, mainly from the old Mughal service class of northern India, began a movement for the reassertion and protection of their interests in the nineteenth century which ended up as the foundation of a separate Muslim state in the twentieth century, was the dominant Muslim story of British India. -

Bangladesh – BGD34387 – Lalpur – Sonapur – Noakhali – Dhaka – Christians – Catholics – Awami League – BNP

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: BGD34387 Country: Bangladesh Date: 25 February 2009 Keywords: Bangladesh – BGD34387 – Lalpur – Sonapur – Noakhali – Dhaka – Christians – Catholics – Awami League – BNP This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please update on the situation for Catholics in Dhaka. 2. Are there any reports to suggest that Christians (or Catholics) tend to support or be associated with the BNP or AL generally, or whether this might depend on local conditions? 3. Are there any reports of a Catholic community in Lalpur (village) or Sonapur (local area) of Noakhali; in particular, their size and whether they are long-established? 4. If so, is there any material to indicate their mistreatment or serious incidents? 5. Please update on the treatment of BNP ‘field workers’ or supporters following the election of the AL Government. Any specific references to Dhaka or Noakhali would be useful. RESPONSE 1. Please update on the situation for Catholics in Dhaka. Question 2 of recent RRT Research Response BGD34378 of 17 February 2009 refers to source information on the situation of Catholics in Dhaka. -

BANGLADESH COUNTRY REPORT April 2004 Country Information

BANGLADESH COUNTRY REPORT April 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Bangladesh April 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of Document 1.1 - 1.7 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.3 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.3 4. History 4.1 - 4.45 Pre-independence: 1947 – 1971 4.1 - 4.4 1972 –1982 4.5 - 4.8 1983 – 1990 4.9 - 4.14 1991 – 1999 4.15 - 4.26 2000 – the present 4.27 - 4.45 5. State Structures 5.1 - 5.51 The constitution 5.1 - 5.3 - Citizenship and Nationality 5.4 - 5.6 Political System 5.7 - 5.13 Judiciary 5.14 - 5.21 Legal Rights /Detention 5.22 - 5.30 - Death Penalty 5.31 – 5.32 Internal Security 5.33 - 5.34 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.35 – 5.37 Military Service 5.38 Medical Services 5.39 - 5.45 Educational System 5.46 – 5.51 6. Human Rights 6.1- 6.107 6.A Human Rights Issues 6.1 - 6.53 Overview 6.1 - 6.5 Torture 6.6 - 6.7 Politically-motivated Detentions 6.8 - 6.9 Police and Army Accountability 6.10 - 6.13 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.14 – 6.23 Freedom of Religion 6.24 - 6.29 Hindus 6.30 – 6.35 Ahmadis 6.36 – 6.39 Christians 6.40 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.41 Employment Rights 6.42 - 6.47 People Trafficking 6.48 - 6.50 Freedom of Movement 6.51 - 6.52 Authentication of Documents 6.53 6.B Human Rights – Specific Groups 6.54 – 6.85 Ethnic Groups Biharis 6.54 - 6.60 The Tribals of the Chittagong Hill Tracts 6.61 - 6.64 Rohingyas 6.65 – 6.66 Women 6.67 - 6.71 Rape 6.72 - 6.73 Acid Attacks 6.74 Children 6.75 - 6.80 - Child Care Arrangements 6.81 – 6.84 Homosexuals 6.85 Bangladesh April 2004 6.C Human Rights – Other Issues 6.86 – 6.89 Prosecution of 1975 Coup Leaders 6.86 - 6.89 Annex A: Chronology of Events Annex B: Political Organisations Annex C: Prominent People Annex D: References to Source Material Bangladesh April 2004 1. -

Title: Women of Agency: the Penned Thoughts of Bengali Muslim

Title: Women of Agency: The Penned Thoughts of Bengali Muslim Women Writers of 9th 20th the Late 1 and Early Century Submitted by: Irteza Binte-Farid In Fulfillment of the Feminist Studies Honors Program Date: June 3, 2013 introduction: With the prolusion of postcolornal literature and theory arising since the 1 9$Os. unearthing subaltern voices has become an admirable task that many respected scholars have undertaken. Especially in regards to South Asia, there has been a series of meticulouslyresearched and nuanced arguments about the role of the subaltern in contributing to the major annals of history that had previously been unrecorded, greatly enriching the study of the history of colonialism and imperialism in South Asia. 20th The case of Bengali Muslim women in India in the late l91 and early century has also proven to be a topic that has produced a great deal of recent literature. With a history of scholarly 19th texts, unearthing the voices of Hindu Bengali middle-class women of late and early 2O’ century, scholars felt that there was a lack of representation of the voices of Muslim Bengali middle-class women of the same time period. In order to counter the overwhelming invisibility of Muslim Bengali women in academic scholarship, scholars, such as Sonia Nishat Amin, tackled the difficult task of presenting the view of Muslim Bengali women. Not only do these new works fill the void of representing an entire community. they also break the persistent representation of Muslim women as ‘backward,’ within normative historical accounts by giving voice to their own views about education, religion, and society) However, any attempt to make ‘invisible’ histories ‘visible’ falls into a few difficulties. -

Country of Origin Information Report Bangladesh Country Overview

European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Bangladesh Country Overview December 2017 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Bangladesh Country Overview December 2017 Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00800 numbers or these calls may be billed. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). Print ISBN 978-92-9494-830-4 doi: 10.2847/19533 BZ-07-17-148-EN-C PDF ISBN 978-92-9494-829-8 doi: 10.2847/34007 BZ-07-17-148-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office 2017 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © International Food Policy Research Institute, A Crowded Market in Dhaka, Bangladesh, 6 May 2010 (https://www.flickr.com/photos/ifpri/4860343116). Neither EASO nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained herein. EASO COI REPORT BANGLADESH: COUNTRY OVERVIEW — 3 Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge the following national asylum and migration departments as the drafters of this report: Bulgaria, State Agency for Refugees (SAR), COI Unit; Italy, National Commission for the Right of Asylum International and EU Affairs, COI unit; United Kingdom, Home Office, Country Policy & Information Team. -

PETRRA - an Experiment BOOK: 6/10 in Pro-Poor Communication - Agricultural Getting Messages to Stakeholders Research

es ADESH erienc ANGL xp B t, ojec A pr earning and e L ETRR of the P PETRRA - an experiment BOOK: 6/10 in pro-poor Communication - agricultural getting messages to stakeholders research Edited by Noel P. Magor, Ahmad Salahuddin, Mamunul Haque, Tapash K. Biswas and Matt Bannerman Poverty Elimination Through Rice Research Assistance (PETRRA), 1999-2004 a project funded by DFID, managed by IRRI in close collaboration with BRRI Book 6. Communication - getting messages to stakeholders Communication brief no. 6 Communication - getting messages to stakeholders Alastair Orr, Fatima Jahan ASe.e Smaal,a Shuhdadilian ,A Mrif.a HNaaqbuie, Jaankdi rNulo eIls lPa.m M Paegteorr INTRODUCTION section. There was a broad two-pronged approach: Communication or getting messages to stakeholders grew in importance over the targeting the government (GO) and life of Poverty Elimination Through Rice non-governmental organisation (NGO) Research Assistance (PETRRA) project; policy makers, donors, research to the point that it was given output-level managers, scientists, and extension status on the logical framework. In other managers; and words it was essential for PETRRA to targeting the end-users of the achieve its purpose-level objectives. innovations, namely, farmers and GO- It could be asked why has communication NGO extension workers. become so important? Public-funded research is for improving the livelihoods of poor households and there has been a THE MAIN MESSAGES growing demand for accountability in delivering impact from that research. At PETRRA SPs can be divided into three one level, the agricultural research categories and each category had its own community has neglected to communicate message to communicate to its audience: its importance in the fight to reduce Category 1: Technology identification, poverty. -

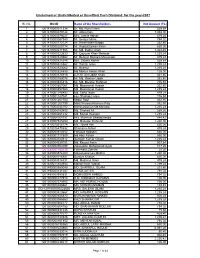

List of Unclaimed Dividend

Unclaimed or Undistributed or Unsettled Cash Dividend for the year-2007 Sl. No. BO ID Name of the Shareholders Net Amount (Tk.) 1 1201470000011334 Dr. Md. Nurul Islam 529.64 2 1201470000079144 Mr. Alaka Das. 7,938.00 3 1201470000079227 Mrs. Jamila Akhter. 479.24 4 1201470000087340 Mr. Serajul Islam. 794.02 5 1201470000173124 Mr. Imran Islam Bappy 352.80 6 1201470000200174 Mr. Asaduzzaman Khan 630.00 7 1201470000271905 Mr. Md. Badrul Alam 1,424.46 8 1201470000323639 Mr. Qayyum Khan Mahbub 1,235.24 9 1201470000329462 Mr. Belayet Hossain Mozumder 479.24 10 1201470000428346 Mrs. Sabina Akther 529.64 11 1201470000428362 Mr. Tanzin Islam 1,235.24 12 1201470000520062 Mr. Ikramul 1,235.24 13 1201470000524459 Md Mokter Hosan Khan 126.00 14 1201470000574918 G.H.M. Arif Uddin Khan 441.66 15 1201470000769078 Mr. Md. Iftekher Uddin 352.80 16 1201470000845416 Mr. Md. Mizanur Rahman 705.60 17 1201470000857067 Md. Mozammel Husain 352.80 18 1201470000857083 Md. Mozammel Husain 1,235.24 19 1201470001146492 Md. Saiful Islam 479.24 20 1201470001147041 kazi Shahidul Islam 176.84 21 1201470001207780 Abdur Rouf 352.80 22 1201470001207799 Most Waresa Khanam Prity 352.80 23 1201470004044792 Moniruzzaman Md.Mostafa 1,235.24 24 1201470004193803 Md. Shahed Ali 265.26 25 1201470004261632 Md. Kamal Hossain 1,235.24 26 1201470004708797 Mrs. Munmun Bhattacharjee 844.42 27 1201470007925659 Md. Masudur Rahman 1,260.00 28 1201470010616174 Ms. Hosna Ara 630.00 29 1201470016475332 Shamima Akhter 479.24 30 1201480000970352 Faruque Hossain 630.00 31 1201480001717909 Md Abul Kalam 630.00 32 1201480003543312 Santosh Kumar Ghosh 1,235.24 33 1201480004339151 Md. -

Iv PENGARUH IDEOLOGI GERAKAN DAKWAH TABLIGH TERHADAP

iv PENGARUH IDEOLOGI GERAKAN DAKWAH TABLIGH TERHADAP PEMBANGUNAN MASJID SEBAGAI PUSAT DAKWAH NURUL ‘ATHIQAH BINTI BAHARUDIN Tesis ini dikemukakan sebagai memenuhi syarat penganugerahan ijazah Doktor Falsafah (Senibina) Fakulti Alam Bina Universiti Teknologi Malaysia NOVEMBER 2016 iii Di tujukan kepada suami tercinta Mohd Fariz Bin Kammil, mama Jamilah Salim, mama Fadzilah Mahmood dan papa Kammil Besah yang tidak putus memberi dorongan, membantu dan mendoakanku, Arwah abah, Baharudin Abdullah yang menjadi pembakar semangat dan dorongan yang sentiasa percaya kebolehan dan tidak sempat melihat kejayaanku… Terima Kasih atas segalanya….. Al-Fatihah iv PENGHARGAAN Segala puji dan syukur ke hadrat Allah S.W.T, dengan rahmat dan kasih sayangnya serta selawat dan salam ke atas junjungan besar Nabi Muhammad S.A.W. beserta seluruh keluarga dan sahabat. Tesis ini dapat diselesaikan dalam jangka masa yang sepatutnya dan dalam keadaan yang mestinya. Penghargaan dan penghormatan dan setinggi ucapan terima kasih di ucapkan kepada penyelia Dr Alice Sabrina Ismail atas segala tunjuk ajar, bimbingan, dorongan, semangat yang tidak putus dan meluangkan masa semaksimum mungkin dalam proses menyelesaikan tesis ini. Penghargaan juga kepada semua tenaga pengajar di Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM) yang menyumbang buah fikian juga PM Dr Mohamed Rashid bin Embi selaku pemeriksa dalam. Penghargaan dan terima kasih yang tidak terhingga juga kepada suami Mohd Fariz Bin Kammil yang membantu dalam kerja-kerja pengumpulan data, memberi dorongan dan semangat yang tidak kenal erti jemu dan putus asa. Ucapan terima kasih juga kepada mama saya dan kedua ibu bapa mertua yang sudi menjaga anakku Insyirah dan membantu bersama membesarkannya sepanjang pengajian dan proses menyelesaikan tesis ini. Doa dan pertolongan mereka sangat dihargai. -

Sheikha Moza Serious Breach and fl Agrant Violations Structed and Kidnapped a Qatari fi Shing China’S President Xi Jinping Was of International Law

QATAR | Page 24 SPORT | Page 1 Qatar’s Adel leads T2 series aft er INDEX DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 2-9, 24 COMMENT 22, 23 Second Aspire Kite REGION 9 BUSINESS 1-5, 17-20 solid fi nish Festival attracted 25,360.00 8,303.34 62.04 ARAB WORLD 9, 10 CLASSIFIED 6-16 +439.00 -62.77 +1.92 INTERNATIONAL 11-21 SPORTS 1-8 over 40,000 visitors in Dubai +1.76% -0.75% +3.19% Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 SUNDAY Vol. XXXIX No. 10754 March 11, 2018 Jumada Il 23, 1439 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals FM in Sudan meeting Qatar informs In brief UN of airspace QATAR | Reaction violations by Qatar slams withdrawal of Jerusalem identity Qatar strongly condemned the Israeli Knesset’s approval of a law UAE, Bahrain authorising the interior minister to withdraw the Jerusalem identity atar has informed the UN Secu- in the region and without regard to Qa- from the Palestinians. In a statement rity Council and the UN Secre- tar’s security and stability.” yesterday, the Foreign Ministry Qtary-General of three violations The Government of Qatar has called described the move as unethical and of Qatar’s airspace by the United Arab upon the Security Council and the completely disregarding international Emirates (UAE) and the Kingdom of United Nations to take the necessary law, international humanitarian law Bahrain. measures under the Charter of the and UN conventions. The statement The message was handed over by HE United Nations to maintain interna- called on the international community the Permanent Representative of Qa- tional peace and security. -

REFUGEECOSATT3.Pdf

+ + + Refugees and IDPs in South Asia Editor Dr. Nishchal N. Pandey + + Published by Consortium of South Asian Think Tanks (COSATT) www.cosatt.org Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS) www.kas.de First Published, November 2016 All rights reserved Printed at: Modern Printing Press Kathmandu, Nepal. Tel: 4253195, 4246452 Email: [email protected] + + Preface Consortium of South Asian Think-tanks (COSATT) brings to you another publication on a critical theme of the contemporary world with special focus on South Asia. Both the issues of refugees and migration has hit the headlines the world-over this past year and it is likely that nation states in the foreseeable future will keep facing the impact of mass movement of people fleeing persecution or war across international borders. COSATT is a network of some of the prominent think-tanks of South Asia and each year we select topics that are of special significance for the countries of the region. In the previous years, we have delved in detail on themes such as terrorism, connectivity, deeper integration and the environment. In the year 2016, it was agreed by all COSATT member institutions that the issue of refugees and migration highlighting the interlinkages between individual and societal aspirations, reasons and background of the cause of migration and refugee generation and the role of state and non-state agencies involved would be studied and analyzed in depth. It hardly needs any elaboration that South Asia has been both the refugee generating and refugee hosting region for a long time. South Asian migrants have formed some of the most advanced and prosperous diasporas in the West. -

Bangladesh: Political and Strategic Developments and U.S

Bangladesh: Political and Strategic Developments and U.S. Interests /name redacted/ Specialist in Asian Affairs June 8, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R44094 Bangladesh: Political and Strategic Developments and U.S. Interests Summary Bangladesh (the former East Pakistan) is a Muslim-majority nation in South Asia, bordering the Bay of Bengal, dominated by low-lying riparian zones. It is the world’s eighth most populous country, with approximately 160 million people housed in a land mass about the size of Iowa. It is a poor nation and suffers from high levels of corruption and a faltering democratic system that has been subject to an array of pressures in recent years. These pressures include a combination of political violence, corruption, weak governance, poverty, demographic and environmental stress, and Islamist militancy. The United States has long-standing supportive relations with Bangladesh and views Bangladesh as a moderate voice in the Islamic world. The U.S. government and Members of Congress have focused on issues related to economic development, humanitarian concerns, labor rights, human rights, good governance, and counterterrorism among other issues as part of the United States’ bilateral relationship with Bangladesh. The Awami League (AL) and the Bangladesh National Party (BNP) dominate Bangladeshi politics. When in opposition, both parties have sought to regain control of the government through demonstrations, labor strikes, and transport blockades. Such mass protests are known as hartals in South Asia. The current AL government of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina was reelected in January 2014 with an overwhelming majority in parliament. Hasina has been in office since 2009. -

List of Trainees of Egp Training

Consultancy Services for “e-GP Related Training” Digitizing Implementation Monitoring and Public Procurement Project (DIMAPPP) Contract Package # CPTU/S-03 Central Procurement Technical Unit (CPTU), IMED Ministry of Planning Training Time Duration: 1st July 2020- 30th June 2021 Summary of Participants # Type of Training No. of Participants 1 Procuring Entity (PE) 876 2 Registered Tenderer (RT) 1593 3 Organization Admin (OA) 59 4 Registered Bank User (RB) 29 Total 2557 Consultancy Services for “e-GP Related Training” Digitizing Implementation Monitoring and Public Procurement Project (DIMAPPP) Contract Package # CPTU/S-03 Central Procurement Technical Unit (CPTU), IMED Ministry of Planning Training Time Duration: 1st July 2020- 30th June 2021 Number of Procuring Entity (PE) Participants: 876 # Name Designation Organization Organization Address 1 Auliullah Sub-Technical Officer National University, Board Board Bazar, Gazipur 2 Md. Mominul Islam Director (ICT) National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 3 Md. Mizanoor Rahman Executive Engineer National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 4 Md. Zillur Rahman Assistant Maintenance Engineer National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 5 Md Rafiqul Islam Sub Assistant Engineer National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 6 Mohammad Noor Hossain System Analyst National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 7 Md. Anisur Rahman Programmer Ministry Of Land Bangladesh Secretariat Dhaka-999 8 Sanjib Kumar Debnath Deputy Director Ministry Of Land Bangladesh Secretariat Dhaka-1000 9 Mohammad Rashedul Alam Joint Director Bangladesh Rural Development Board 5,Kawranbazar, Palli Bhaban, Dhaka-1215 10 Md. Enamul Haque Assistant Director(Construction) Bangladesh Rural Development Board 5,Kawranbazar, Palli Bhaban, Dhaka-1215 11 Nazneen Khanam Deputy Director Bangladesh Rural Development Board 5,Kawranbazar, Palli Bhaban, Dhaka-1215 12 Md.