JRA 29 1 Bookreview 190..192

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India Gyanendra Pandey CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Remembering Partition Violence, Nationalism and History in India Through an investigation of the violence that marked the partition of British India in 1947, this book analyses questions of history and mem- ory, the nationalisation of populations and their pasts, and the ways in which violent events are remembered (or forgotten) in order to en- sure the unity of the collective subject – community or nation. Stressing the continuous entanglement of ‘event’ and ‘interpretation’, the author emphasises both the enormity of the violence of 1947 and its shifting meanings and contours. The book provides a sustained critique of the procedures of history-writing and nationalist myth-making on the ques- tion of violence, and examines how local forms of sociality are consti- tuted and reconstituted by the experience and representation of violent events. It concludes with a comment on the different kinds of political community that may still be imagined even in the wake of Partition and events like it. GYANENDRA PANDEY is Professor of Anthropology and History at Johns Hopkins University. He was a founder member of the Subaltern Studies group and is the author of many publications including The Con- struction of Communalism in Colonial North India (1990) and, as editor, Hindus and Others: the Question of Identity in India Today (1993). This page intentionally left blank Contemporary South Asia 7 Editorial board Jan Breman, G.P. Hawthorn, Ayesha Jalal, Patricia Jeffery, Atul Kohli Contemporary South Asia has been established to publish books on the politics, society and culture of South Asia since 1947. -

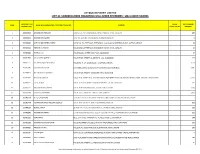

Group Housing

LIST OF ALLOTED PROPERTIES DEPARTMENT NAME- GROUP HOUSING S# RID PROPERTY NO. APPLICANT NAME AREA 1 60244956 29/1013 SEEMA KAPUR 2,000 2 60191186 25/K-056 CAPT VINOD KUMAR, SAROJ KUMAR 128 3 60232381 61/E-12/3008/RG DINESH KUMAR GARG & SEEMA GARG 154 4 60117917 21/B-036 SUDESH SINGH 200 5 60036547 25/G-033 SUBHASH CH CHOPRA & SHWETA CHOPRA 124 6 60234038 33/146/RV GEETA RANI & ASHOK KUMAR GARG 200 7 60006053 37/1608 ATEET IMPEX PVT. LTD. 55 8 39000209 93A/1473 ATS VI MADHU BALA 163 9 60233999 93A/01/1983/ATS NAMRATA KAPOOR 163 10 39000200 93A/0672/ATS ASHOK SOOD SOOD 0 11 39000208 93A/1453 /14/AT AMIT CHIBBA 163 12 39000218 93A/2174/ATS ARUN YADAV YADAV YADAV 163 13 39000229 93A/P-251/P2/AT MAMTA SAHNI 260 14 39000203 93A/0781/ATS SHASHANK SINGH SINGH 139 15 39000210 93A/1622/ATS RAJEEV KUMAR 0 16 39000220 93A/6-GF-2/ATS SUNEEL GALGOTIA GALGOTIA 228 17 60232078 93A/P-381/ATS PURNIMA GANDHI & MS SHAFALI GA 200 18 60233531 93A/001-262/ATS ATUULL METHA 260 19 39000207 93A/0984/ATS GR RAVINDRA KUMAR TYAGI 163 20 39000212 93A/1834/ATS GR VIJAY AGARWAL 0 21 39000213 93A/2012/1 ATS KUNWAR ADITYA PRAKASH SINGH 139 22 39000211 93A/1652/01/ATS J R MALHOTRA, MRS TEJI MALHOTRA, ADITYA 139 MALHOTRA 23 39000214 93A/2051/ATS SHASHI MADAN VARTI MADAN 139 24 39000202 93A/0761/ATS GR PAWAN JOSHI 139 25 39000223 93A/F-104/ATS RAJESH CHATURVEDI 113 26 60237850 93A/1952/03 RAJIV TOMAR 139 27 39000215 93A/2074 ATS UMA JAITLY 163 28 60237921 93A/722/01 DINESH JOSHI 139 29 60237832 93A/1762/01 SURESH RAINA & RUHI RAINA 139 30 39000217 93A/2152/ATS CHANDER KANTA -

List of Life Members As on 20Th January 2021

LIST OF LIFE MEMBERS AS ON 20TH JANUARY 2021 10. Dr. SAURABH CHANDRA SAXENA(2154) ALIGARH S/O NAGESH CHANDRA SAXENA POST HARDNAGANJ 1. Dr. SAAD TAYYAB DIST ALIGARH 202 125 UP INTERDISCIPLINARY BIOTECHNOLOGY [email protected] UNIT, ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 202 002 11. Dr. SHAGUFTA MOIN (1261) [email protected] DEPT. OF BIOCHEMISTRY J. N. MEDICAL COLLEGE 2. Dr. HAMMAD AHMAD SHADAB G. G.(1454) ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY 31 SECTOR OF GENETICS ALIGARH 202 002 DEPT. OF ZOOLOGY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY 12. SHAIK NISAR ALI (3769) ALIGARH 202 002 DEPT. OF BIOCHEMISTRY FACULTY OF LIFE SCIENCE 3. Dr. INDU SAXENA (1838) ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY, ALIGARH 202 002 HIG 30, ADA COLONY [email protected] AVANTEKA PHASE I RAMGHAT ROAD, ALIGARH 202 001 13. DR. MAHAMMAD REHAN AJMAL KHAN (4157) 4/570, Z-5, NOOR MANZIL COMPOUND 4. Dr. (MRS) KHUSHTAR ANWAR SALMAN(3332) DIDHPUR, CIVIL LINES DEPT. OF BIOCHEMISTRY ALIGARH UP 202 002 JAWAHARLAL NEHRU MEDICAL COLLEGE [email protected] ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 202 002 14. DR. HINA YOUNUS (4281) [email protected] INTERDISCIPLINARY BIOTECHNOLOGY UNIT ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY 5. Dr. MOHAMMAD TABISH (2226) ALIGARH U.P. 202 002 DEPT. OF BIOCHEMISTRY [email protected] FACULTY OF LIFE SCIENCES ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY 15. DR. IMTIYAZ YOUSUF (4355) ALIGARH 202 002 DEPT OF CHEMISTRY, [email protected] ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY, ALIGARH, UP 202002 6. Dr. MOHAMMAD AFZAL (1101) [email protected] DEPT. OF ZOOLOGY [email protected] ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 202 002 ALLAHABAD 7. Dr. RIAZ AHMAD(1754) SECTION OF GENETICS 16. -

Institute of Business Administration, Karachi Bba, Bs

FINAL RESULT - FALL 2020 ROUND 1 Announced on Tuesday, February 25, 2020 INSTITUTE OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, KARACHI BBA, BS (ACCOUNTING & FINANCE), BS (ECONOMICS) & BS (SOCIAL SCIENCES) ADMISSIONS TEST HELD ON SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2020 (FALL 2020, ROUND 1) LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR DIRECT ADMISSION (BSAF PROGRAM) SAT Test Math Eng TOTAL Maximum Marks 800 800 1600 Cut-Off Marks 600 600 1410 Math Eng Total IBA Test MCQ MCQ MCQ Maximum Marks 180 180 360 Cut-Off Marks 100 100 256 Seat S. No. App No. Name Father's Name No. 1 18 845 FABIHA SHAHID SHAHIDSIDDIQUI 132 136 268 2 549 1510 MUHAMMAD QASIM MAHMOOD AKHTAR 148 132 280 3 558 426 MUHAMMAD MUTAHIR ABBAS AMAR ABBAS 144 128 272 4 563 2182 ALI ABDULLAH MUHAMMAD ASLAM 136 128 264 5 1272 757 MUHAMMAD DANISH NADEEM MUHAMMAD NADEEM TAHIR 136 128 264 6 2001 1 MUHAMMAD JAWWAD HABIB MUHAMMAD NADIR HABIB 160 100 260 7 2047 118 MUHAMMAD ANAS LIAQUAT ALI 148 128 276 8 2050 125 HAFSA AZIZ AZIZAHMED 128 136 264 9 2056 139 MUHAMMAD SALMAN ANWAR MUHAMMAD ANWAR 156 132 288 10 2086 224 MOHAMMAD BADRUDDIN RIND BALOCH BAHAUDDIN BALOCH 144 112 256 11 2089 227 AHSAN KAMAL LAGHARI GHULAM ALI LAGHARI 136 160 296 12 2098 247 SYED MUHAMMAD RAED SYED MUJTABA NADEEM 152 132 284 13 2121 304 AREEB AHMED BAIG ILHAQAHMED BAIG 108 152 260 14 2150 379 SHAHERBANO ‐ ABDULSAMAD SURAHIO 148 124 272 15 2158 389 AIMEN ATIQ SYED ATIQ UR REHMAN 148 124 272 16 2194 463 MUHAMMAD SAAD MUHAMMAD ABBAS 152 136 288 17 2203 481 FARAZ NAWAZ MUHAMMAD NAWAZ 132 128 260 18 2210 495 HASNAIN IRFAN IRFAN ABDULAZIZ 128 132 260 19 2230 -

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Mohammad Raisur Rahman certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India Committee: _____________________________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________________________ Cynthia M. Talbot _____________________________________ Denise A. Spellberg _____________________________________ Michael H. Fisher _____________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India by Mohammad Raisur Rahman, B.A. Honors; M.A.; M.Phil. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the fond memories of my parents, Najma Bano and Azizur Rahman, and to Kulsum Acknowledgements Many people have assisted me in the completion of this project. This work could not have taken its current shape in the absence of their contributions. I thank them all. First and foremost, I owe my greatest debt of gratitude to my advisor Gail Minault for her guidance and assistance. I am grateful for her useful comments, sharp criticisms, and invaluable suggestions on the earlier drafts, and for her constant encouragement, support, and generous time throughout my doctoral work. I must add that it was her path breaking scholarship in South Asian Islam that inspired me to come to Austin, Texas all the way from New Delhi, India. While it brought me an opportunity to work under her supervision, I benefited myself further at the prospect of working with some of the finest scholars and excellent human beings I have ever known. -

Acknowledgement

Acknowledgement We are extremely grateful to the following members of the medical profession from Pakistan and Overseas for sparing their precious time to review the manuscript during the year, 2012. Reviewer’s No. of Reviewer’s No. of Reviewer’s No. of Name Manuscript Name Manuscript Name Manuscript Reviewed Reviewed Reviewed A Razaque Shaihk, Hyderabad 2 Jahan Ara Pal, Karachi 5 Saba Sohail, Karachi 5 A Sattar Hashim, Karachi 2 Kamaran Hafeez, Karachi 6 Saeed Minhas, Karachi 4 Abdul Basit, Karachi 3 Khadigeh Nasri, Iran 1 Sajid Rashid, Multan 2 Abdul Haque, Faisalabad 1 Khaleeq-uz-Zaman, Islamabad 1 Saleem Marfani, Karachi 1 Abdul Rehman, Bahawalpur 3 Khalid Nawaz, Lahore 1 Saleem Sadiq, Karachi 3 Abdul Salam, Bangladesh 6 Khan Shah Zaman Khan, Karachi 2 Salman Ahmed Tipu, Rawalpindi 3 Abdul Samad, Oman 4 Laiq Hussain Siddiqui, Lahore 2 Sameen Afzal Junejo, Hyderabad 3 Ahmad Badar, Saudi Arabia 2 M Asif Qureshi, Karachi 1 Sarwat Ara, Faisalabad 1 Akhtar Sherin, Kohat 2 M Aslam, Lahore 4 Seema Bibi, Hyderabad 3 Ali Mohammad 1 M Azeem Aslam, Islamabad 1 Seema Mumtaz, Karachi 1 Sabzghabaee, Iran M Sarwar, Karachi 3 Shahid Hameed, Lahore 4 M Waqar Rabbani, Multan 3 Ameer Malik, Bahawalpur 1 Shahid Mahmood Baig, 2 Anisuddin Bhatti, Karachi 2 M Zubair, Karachi 1 Faisalabad Anwar Naqvi, Karachi 1 M. Akbar Chaudhry, Lahore 5 Shahida Khawaja, Lahore 2 Aqeel Safdar, Islamabad 1 M. Aslam Maj. Gen., Islamabad 3 Shakeel Baig, Karachi 1 Arturo Langa, Scotland, UK 1 M. Zaman Shaikh, Karachi 2 Shamim Qureshi, Karachi 2 Arif-ur-Rehman, Karachi 5 Mahfooz-ur-Rehman, Lahore 3 Shams Nadeem Alam, Karachi 3 Ata Mahmood Poor, Iran 4 Mansoor Ahmed, Karachi 1 Shaukat Ali, Karachi 4 Azeem Aslam, Islamabad 1 Maqbool H. -

Bangladesh: Political and Strategic Developments and U.S

Bangladesh: Political and Strategic Developments and U.S. Interests /name redacted/ Specialist in Asian Affairs June 8, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R44094 Bangladesh: Political and Strategic Developments and U.S. Interests Summary Bangladesh (the former East Pakistan) is a Muslim-majority nation in South Asia, bordering the Bay of Bengal, dominated by low-lying riparian zones. It is the world’s eighth most populous country, with approximately 160 million people housed in a land mass about the size of Iowa. It is a poor nation and suffers from high levels of corruption and a faltering democratic system that has been subject to an array of pressures in recent years. These pressures include a combination of political violence, corruption, weak governance, poverty, demographic and environmental stress, and Islamist militancy. The United States has long-standing supportive relations with Bangladesh and views Bangladesh as a moderate voice in the Islamic world. The U.S. government and Members of Congress have focused on issues related to economic development, humanitarian concerns, labor rights, human rights, good governance, and counterterrorism among other issues as part of the United States’ bilateral relationship with Bangladesh. The Awami League (AL) and the Bangladesh National Party (BNP) dominate Bangladeshi politics. When in opposition, both parties have sought to regain control of the government through demonstrations, labor strikes, and transport blockades. Such mass protests are known as hartals in South Asia. The current AL government of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina was reelected in January 2014 with an overwhelming majority in parliament. Hasina has been in office since 2009. -

Sustainable Solid Waste Management Through 3R Strategy in Gazipur City Corporation

Sustainable Solid Waste Management Through 3R Strategy in Gazipur City Corporation By ABDULLAH RUMI SHISHIR PROMI ISLAM ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY (IUT) 2016 i Sustainable Solid Waste Management Through 3R Strategy in Gazipur City Corporation By Abdullah Rumi Shishir (Student id 125423) Promi Islam (Student id 125447) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN CIVIL ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY NOVEMBER, 2015 iii iv APPROVAL The thesis titled ―Sustainable solid waste management through 3R strategy in Gazipur city corporation‖ submitted by Abdullah Rumi Shishir (Student ID 125423), Promi Islam (Student ID 125447) of Academic Year 2012-16 has been found as satisfactory and accepted as partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Civil Engineering. SUPERVISOR DR. MD. REZAUL KARIM Professor Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering (CEE) Islamic University of Technology (IUT) v DECLARATION We hereby declare that the undergraduate project work reported in this thesis has been performed by us and this work has not been submitted elsewhere for the award of any degree or diploma. November 2016 Abdullah Rumi Shishir (125423) Promi Islam (125447) vi DEDICATED TO OUR BELOVED PARENTS vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the name of Allah, Most Gracious, Most Merciful All praises belongs to the almighty Allah for giving us the strength and courage to successfully complete our B.Sc. thesis. We would like to express our sincere appreciation to our Supervisor Dr. Md. Rezaul Karim, Professor, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Islamic University of Technology (IUT), for his generous guidance, advice and encouragement in supervising us. -

List of Unclaimed Shares and Dividend

ATTOCK REFINERY LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS REGARDING UNCLAIMED DIVIDENDS / UNCLAIMED SHARES FOLIO NO / CDC SHARE NET DIVIDEND S/NO. NAME OF SHAREHOLDER / CERTIFICATE HOLDER ADDRESS ACCOUNT NO. CERTIFICATES AMOUNT 1 208020582 MUHAMMAD HAROON DASKBZ COLLEGE, KHAYABAN-E-RAHAT, PHASE-VI, D.H.A., KARACHI 450 2 208020632 MUHAMMAD SALEEM SHOP NO.22, RUBY CENTRE,BOULTON MARKETKARACHI 8 3 307000046 IGI FINEX SECURITIES LIMITED SUIT # 701-713, 7TH FLOOR, THE FORUM, G-20, BLOCK 9, KHAYABAN-E-JAMI, CLIFTON, KARACHI 15 4 307013023 REHMAT ALI HASNIE HOUSE # 96/2, STREET # 19, KHAYABAN-E-RAHAT, DHA-6, KARACHI. 15 5 307020846 FARRUKH ALI HOUSE # 246-A, STREET # 39, F-11/3, ISLAMABAD 67 6 307022966 SALAHUDDIN QURESHI HOUSE # 785, STREET # 11, SECTOR G-11/1, ISLAMABAD. 174 7 307025555 ALI IMRAN IQBAL MOTIWALA HOUSE NO. H-1, F-48-49, BLOCK - 4, CLIFTON, KARACHI. 2,550 8 307026496 MUHAMMAD QASIM C/O HABIB AUTOS, ADAM KHAN, PANHWAR ROAD, JACOBABAD. 2,085 9 307028922 NAEEM AHMED SIDDIQUI HOUSE # 429, STREET # 4, SECTOR # G-9/3, ISLAMABAD. 7 10 307032411 KHALID MEHMOOD HOUSE # 10 , STREET # 13 , SHAHEEN TOWN, POST OFFICE FIZAI, C/O MADINA GERNEL STORE, CHAKLALA, RAWALPINDI. 6,950 11 307034797 FAZAL AHMED HOUSE # A-121,BLOCK # 15,RAILWAY COLONY , F.B AREA, KARACHI 225 12 307037535 NASEEM AKHTAR AWAN HOUSE # 183/3 MUNIR ROAD , LAHORE CANTT LAHORE . 1,390 13 307039564 TEHSEEN UR REHMAN HOUSE # S-5, JAMI STAFE LANE # 2, DHA, KARACHI. 3,475 14 307041594 ATTIQ-UR-REHMAN C/O HAFIZ SHIFATULLAH,BADAR GENERALSTORE,SHAMA COLONY,BEGUM KOT,LAHORE 7 15 307042774 MUHAMMAD NASIR HUSSAIN SIDDIQUI HOUSE-A-659,BLOCK-H, NORTH NAZIMABAD, KARACHI. -

Annotated Bibliography of National Institute of Malaria Research (Publications: 2011-2015)

Annotated Bibliography of NIMR (Publications: 2011-2015) NIMR Library Annotated Bibliography of National Institute of Malaria Research (Publications: 2011-2015) Compiled and Edited by Md. Rashid Perwez Assistant Library and Information Officer Library and Information Centre ICMR-National Institute of Malaria Research Sector-8, Dwarka, New Delhi-110077 Email: [email protected]; Website: https://nimr.icmr.org.in Annotated Bibliography of NIMR (Publications: 2011-2015) NIMR Library Annotated Bibliography of National Institute of Malaria Research Publications (2011-2015) Contents Page no. Master List-Titles: A-Z 1. Titles: A-Z- 2011 1 2. Titles: A-Z- 2012 58 3. Titles: A-Z- 2013 99 4. Titles: A-Z- 2014 138 5. Titles: A-Z- 2015 177 6. Books: A-Z- 2011-2015 217 Index 7. NIMR Author(s): A-Z 224 8. Sources(s): A-Z 233 9. Publisher(s): A-Z 240 Annotated Bibliography of NIMR (Publications: 2011-2015) NIMR Library Master List Titles: A-Z 2011 1. Mathur A, Singh R, Yousuf S, Bhardwaj A, Verma SK, Babu P, Gupta V, Prasad GBKS, Dua VK. Antifungal activity of some plant extracts against clinical pathogens. Adv Appl Sci Res 2011; 2(2): 260-4. ABSTRACT The antifungal activity and minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of various plant extracts in different solvents such as hydro-alcohol (50 % v/v) and hexane of plants traditionally used as medicines as Valeriana jatamansi (Sugandhbala), Coleus barbatus (Pathar choor), Berberis aristata (Kingore), Asparagus racemosus (Satrawal), Andrographis paniculata (Kalmegha), Achyranthes aspera (Latjiri), Tinospora cordifolia (Giloei), Plantago depressa (Isabgol) were evaluated against Aspergillus niger and Candida albicans. -

Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal La Revue De Santé De La Méditerranée Orientale

Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal La Revue de Santé de la Méditerranée orientale املجلد العرشون / عدد Volume 20 / No. 9 9 أيلول / سبتمرب September/Septembre 2014 Members of the WHO Regional Committee for the Eastern Mediterranean املجلة الصحية لرشق املتوسط Afghanistan . Bahrain . Djibouti . Egypt . Islamic Republic of Iran . Iraq . Jordan . Kuwait . Lebanon هى املجلة الرسمية التى تصدر عن املكتب اﻹقليمى لرشق املتوسط بمنظمة الصحة العاملية. وهى منرب لتقديم Libya . Morocco . Oman . Pakistan . Palestine . Qatar . Saudi Arabia . Somalia . Sudan . Syrian Arab السياسات واملبادرات اجلديدة ىف اخلدمات الصحية والرتويج هلا، ولتبادل اﻵراء واملفاهيم واملعطيات الوبائية Republic . Tunisia . United Arab Emirates . Yemen ونتائج اﻷبحاث وغري ذلك من املعلومات، وخاصة ما يتعلق منها بإقليم رشق املتوسط. وهى موجهة إىل كل أعضاء املهن الصحية، والكليات الطبية وسائر املعاهد التعليمية، وكذا املنظامت غري احلكومية املعنية، واملراكز املتعاونة مع منظمة الصحة العاملية واﻷفراد املهتمني بالصحة ىف اﻹقليم وخارجه. EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN HEALTH JOURNAL البلدان أعضاء اللجنة اﻹقليمية ملنظمة الصحة العاملية لرشق املتوسط IS the official health journal published by the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office of the World Health Organization. It is a forum for the presentation and promotion of new policies and initiatives in health services; and for the exchange of ideas, con- اﻷردن . أفغانستان . اﻹمارات العربية املتحدة . باكستان . البحرين . تونس . ليبيا . مجهورية إيران اﻹسﻻمية .cepts, epidemiological data, research findings and other information, with special reference to the Eastern Mediterranean Region اجلمهورية العربية السورية . اليمن . جيبويت . السودان . الصومال . العراق . عُ ام ن . فلسطني . قطر . الكويت . لبنان . مرص -It addresses all members of the health profession, medical and other health educational institutes, interested NGOs, WHO Col laborating Centres and individuals within and outside the Region. -

SACM-November 2020

SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF PEACE AND CONFLICT 9 NOVEMBER 2020 South Asia Conflict Monitor monthly newsletter on terrorism, violence and armed conflict… COUNTRY NEWS ROUNDUP: OCTOBER 2020 AFGHANISTAN MAJOR EVENTS: October 05: Tariq Arian, spokesman for the Ministry of Interior (MoI), said that a group under the Taliban's command is involved in the targeted killings in cities across Afghanistan. Around 17 member of this covert group were arrested by the Security Forces and they have reportedly confessed about the group. Nearly 70 civilians were killed, and more than 140 others were wounded in the last two weeks in magnetic mine and roadside mine blasts in the country. (Tolo News) October 12: Nato Commander Scott Miller has called on the Taliban to stop their attacks in Helmand province, as it is not consistent with the US-Taliban agreement and that undermines the ongoing Afghan peace talks. US Forces-Afghanistan (USFOR-A) spokesman Sonny Leggett has said that the US forces will continue to provide support to Afghan forces under attack by the Taliban. (Twitter) October 16: Head of the High Council for National Reconciliation (HCNR), Mr Abdullah Abdullah said that a return of the Taliban’s Emirate is unacceptable to Afghans. He emphasised on the need for unity among Afghans and said violence will not lead the country to peace. (HeartofAsia) October 21: NATO allies and partners discussed contributions for 2021 and reiterated their commitment to providing financial support to the Afghan security forces through 2024. A Statement said, “Today’s commitments help underpin the confidence that our financial support to the Afghan security forces will continue to be strong beyond 2020.