If I Ever Lose My Way: a Writer Shares What Has Made Crawford Path a Touchstone for Her

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In This Issue: Saturday, November 3 Highland Center, Crawford Notch, NH from the Chair

T H E O H A S S O C I A T I O N 17 Brenner Drive, Newton, New Hampshire 03858 The O H Association is former employees of the AMC Huts System whose activities include sharing sweet White Mountain memories. 2018 Fall Reunion In This Issue: Saturday, November 3 Highland Center, Crawford Notch, NH From the Chair .......... 2 Poetry & Other Tidbits .......... 3 1pm: Hike up Mt. Avalon, led by Doug Teschner (meet Fall Fest Preview .......... 4 at Highland Center Fastest Known Times (FKTs) .......... 6 3:30-4:30pm: Y-OH discussion session led by Phoebe “Adventure on Katahdin” .......... 9 Howe. Be part of the conversation on growing the OHA Cabin Photo Project Update .......... 10 younger and keeping the OHA relevant in the 21st 2019 Steering Committee .......... 11 century. Meet in Thayer Hall. OHA Classifieds .......... 12 4:30-6:30pm: Acoustic music jam! Happy Hour! AMC “Barbara Hull Richardson” .......... 13 Library Open House! Volunteer Opportunities .......... 16 6:30-7:30pm: Dinner. Announcements .......... 17 7:45-8:30pm: Business Meeting, Awards, Announce- Remember When... .......... 18 ments, Proclamations. 2018 Fall Croos .......... 19 8:30-9:15pm: Featured Presentation: “Down Through OHA Merchandise .......... 19 the Decades,” with Hanque Parker (‘40s), Tom Deans Event News .......... 20 (‘50s), Ken Olsen (‘60s), TBD (‘70s), Pete & Em Benson Gormings .......... 21 (‘80s), Jen Granducci (‘90s), Miles Howard (‘00s), Becca Obituaries .......... 22 Waldo (‘10s). “For Hannah & For Josh” .......... 24 9:15-9:30pm: Closing Remarks & Reminders Trails Update .......... 27 Submission Guidelines .......... 28 For reservations, call the AMC at 603-466-2727. Group # 372888 OH Reunion Dinner, $37; Rooms, $73-107. -

6–8–01 Vol. 66 No. 111 Friday June 8, 2001 Pages 30801–31106

6–8–01 Friday Vol. 66 No. 111 June 8, 2001 Pages 30801–31106 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 19:13 Jun 07, 2001 Jkt 194001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\08JNWS.LOC pfrm04 PsN: 08JNWS 1 II Federal Register / Vol. 66, No. 111 / Friday, June 8, 2001 The FEDERAL REGISTER is published daily, Monday through SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Friday, except official holidays, by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, PUBLIC Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Act (44 U.S.C. Subscriptions: Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Committee of Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Superintendent of Assistance with public subscriptions 512–1806 Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 is the exclusive distributor of the official edition. General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 Single copies/back copies: The Federal Register provides a uniform system for making available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Paper or fiche 512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and Assistance with public single copies 512–1803 Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general FEDERAL AGENCIES applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published Subscriptions: by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public interest. Paper or fiche 523–5243 Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions 523–5243 Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

Northcountry News Northcountry News

SUPPORTING ALL THAT IS LOCAL FOR OVER 25 YEARS! NNOORRTTHHCCOOUUNNTTRRYY FREE EEWWSS NN Tom Sears Photo SINCE APRIL 1989 g READ THROUGHOUT THE NORTH COUNTRY & BEYOND g APRIL 10, 2015 In New Hampshire - Bath, Benton, Bethlehem, Bristol, Campton, Canaan, Dalton, Dorchester, East Haverhill, Easton, Franconia, Glencliff, Groton, Haverhill, Hebron, Landaff, Lincoln, Lisbon, Littleton, Lyman, Monroe, North Haverhill, North Woodstock, Orford, Piermont, Pike, Plymouth, Rumney, Sugar Hill, Swiftwater, Thornton, Warren, Waterville Valley, Wentworth, and Woodsville. In Vermont - Bradford, Corinth, Fairlee, Groton, Newbury, South Ryegate and Wells River Northcountry News • PO Box 10 • Warren, NH 03279 • 603-764-5807 Oliverian, An Alternative High School, Gives Back____________________________ CYAN MAGENTA By: Olivia Acker, munity members to craft hand- Maya Centeno, and made bowls, and then and eat YELLOW Hannah Greatbatch soup together out of the donated bowls. Participants are encour- Have you heard of the aged to keep their bowls in Empty Bowl Project? exchange for a donation to a local organization dedicated to The Empty Bowl Project, an feeding the hungry. BLACK (Page 1) international fundraiser aiming to end hunger around the world, Bessa Axelrod and Liz has come to the Upper Valley. Swindell, teachers at the The project, which originated in Oliverian School in Pike, NH, The American Robin usually means it is a sign of spring. Let’s hope they are here to stay for Michigan in 1990, invites com- Story continues on page A2 a while! - Duane Cross Photo. (www.duanecrosspics.com) SKIP’S GUN SHOP Buy • Sell • Trade 837 Lake St. The area's C.M. Whitcher first choice, for Bristol, NH Transfer Facility furniture and New & Used Firearms mattresses. -

Portland Daily Press: October 24, 1876

PORTLAND m DAILY PRESS. 'IWIMlim——— U—>——U—————M—1—1— —* —— llil WTll— W III III 111 l| Wllimu—WWI1 1———T^***"*—WT———M—IBMMBLMI—.IUWH JI.11I ^"r~n~—n— iumuhuu LtxuiunLjujMm——a——m—n——— ESTABLISHED JUNE 23, 1862..--Y0L. U. PORTLAND, TUESDAY MORNING, OCTOBER 24. 1876. TERMS $8.00 PER ANNUMjINADYANCE. ENTERTAINMENTS. ENTERTAINMENTS. WANTS. BOARD. Db. Hamlin seems to prefer that Turkey _____ THE PRESS. _MISCELLANEOUS._ should not become a Christian State unless it Business Wanted, Board. can become his particular kind. This $11 CENTENNIAL J $11 Tuesday istg feeling TWO EXHIBITIONS a or mormyg, oct. 24, $11 party with good experience, (chiefly in flour,) ii.’gcntlcmen'XIarg efront ronmw) may be Christian, but it looks more like sec- CENTENNIAL ! $11 BY and having a few thousand dollars in cash. FOIt»* 31 JELjI hTKBET. THE octl4 tarian -OF- PIANO-FORTE WAR Address .-A. B. B. B eod2w* bigotry. We do not communi- -- read anonymous letters and $11 CENTENNIAL ! $11 P. O. 1 —— still and while oct2Id2w»_Portland cations. The name and address of the writer are In $11 goes on, most other first-class makers are quarreling Boarders Wauled. CENTENNIAL J $11 as to who received TIIE All cases indispensable, not necessarily for publication Our New York Letter. FIRST PRIZE at the Centennial, the fflWG single gentlemen and a number of table but as a ART PICTURES Wanted ! JL boarders can find excellent accommodation at guaranty of good faith. Don’t a Second-Class Route w hen go by 2U4 Congress street, up oc20-dlw We cannot undeitake to return or reserve commu- — AND — Blairs,_ (mu the First-Class Route you go b.v lO YOUNG MEN lO nications that are not used. -

Randolph Mountain Club Newsletter

12 Randolph Mountain Club Newsletter “… sharing the collective knowledge of its members …” June 2018 0 0.5 1 2 Miles Crawford Project Strip Map G A R B C E O S N U D I O e S N S c L D F E 0 N L t A . i R U 1 o Y G 2 n L I m 9 N E i r le ive rook R s lay B suc C R oo k U on o P m o S m r LL A B E n L W L JE rso E e ff W e J JE O M W O E N S S E s T AVIN R 8 S D UC k OS e I R NO D o O l AMM E o i r H n B C T y o a O m i N w f t L l N I a T A O c 2 H U S R C R T e 4 E K . W F E F R S O 0 M JE N S A N E N R I LI A O V NS V A HE I A R N D E N A SO M UT R H E SID K E C N E U D T R A M G o E n IN r P o L e A B B r A o S o E k R S VE T SO A OS T CR IO N MA N ER R CK D TU S N O M L O A W N C U CAM T EL - O F F 7 Lakes of the Clouds n s S 0 e tio il . -

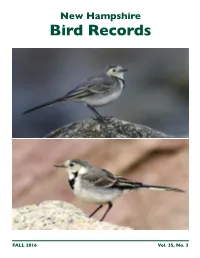

NH Bird Records

New Hampshire Bird Records FALL 2016 Vol. 35, No. 3 IN HONOR OF Rob Woodward his issue of New Hampshire TBird Records with its color cover is sponsored by friends of Rob Woodward in appreciation of NEW HAMPSHIRE BIRD RECORDS all he’s done for birds and birders VOLUME 35, NUMBER 3 FALL 2016 in New Hampshire. Rob Woodward leading a field trip at MANAGING EDITOR the Birch Street Community Gardens Rebecca Suomala in Concord (10-8-2016) and counting 603-224-9909 X309, migrating nighthawks at the Capital [email protected] Commons Garage (8-18-2016, with a rainbow behind him). TEXT EDITOR Dan Hubbard In This Issue SEASON EDITORS Rob Woodward Tries to Leave New Hampshire Behind ...........................................................1 Eric Masterson, Spring Chad Witko, Summer Photo Quiz ...............................................................................................................................1 Lauren Kras/Ben Griffith, Fall Fall Season: August 1 through November 30, 2016 by Ben Griffith and Lauren Kras ................2 Winter Jim Sparrell/Katie Towler, Concord Nighthawk Migration Study – 2016 Update by Rob Woodward ..............................25 LAYOUT Fall 2016 New Hampshire Raptor Migration Report by Iain MacLeod ...................................26 Kathy McBride Field Notes compiled by Kathryn Frieden and Rebecca Suomala PUBLICATION ASSISTANT Loon Freed From Fishing Line in Pittsburg by Tricia Lavallee ..........................................30 Kathryn Frieden Osprey vs. Bald Eagle by Fran Keenan .............................................................................31 -

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Serials Collection

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Serials Collection : Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Serials Collection Rochester Public Library Reference Book Not For Circulation Form la Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Serials Collection ? llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll 3 9077 03099649 3 Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Serials Collection PROCEEDINGS OF THE Rochester Academy of Science Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Serials Collection PROCEEDINGS u OF THE Rochester Academy of Science hi VOLUME 6 October, 1919, to October, 1929 Rochester, n. y. PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY 1929 Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Serials Collection OFFICERS OF THE ACADEMY 1920-1929 L. English, 1920-1921. F. W. C. Meyer, 1922-1925. President, Cogswell Bentley, 1926-1927. (GeorgeWilliam H. Boardman, 1928-1929. Florus R. Baxter, 1920. J. L. Roseboom, 1921. First Vice-president, . John R. Murlin, 1922-1924. H. H. Covell, 1925-1927. |L. E. Jewell, 1928-1929. 'J. L. Roseboom, 1920. John R. Murlin, 1921. H. H. Covell, 1922-1924. Second Vice-president, A. C. Hawkins, 1925-1926. Arthur C. Parker, 1927. C. Messerschmidt, 1928-1929. Secretary, Milroy N. Stewart, 1920-1929. Treasurer, George Wendt, 1920-1929. Librarian, Alice H. Brown, 1920-1929. Corresponding Secretary, William D. Merrell, 1920-1921. COUNCILLORS Elective Florence Beckwith, 1920-1929. William H. Boardman, 1923-1927. Herman' L. Fairchild, 1920-1929. Alfred C. Hawkins, 1923-1925. Warren A. Matthews, 1920-1927. F. W. C. Meyer, 1926-1929. Milton S. Baxter, 1920-1922. William D. Merrell, 1926-1928. Charles C. Zoller, 1920-1922. Arthur C. -

Presidentials Hike

Presidentials – White Mountains – Carroll, NH Length Difficulty Streams Views Solitude Camping 21.4 mls Hiking Time: 2.5 Days Elev. Gain: 7,800 ft Parking: Parking is near the AMC Highland Center Lodge. The Presidential Range in the White Mountains of NH is a true bucket list hike. Hiking above treeline for most of the hike will give some of the best views we have seen in the Eastern U.S. Make no mistake, it will take some effort to get to those views and then you can enjoy the hospitality of AMC's famous White Mountain Huts at the end of each day. There is also the potential for severe weather year round so go prepared. This is one hike you should put on your bucket list! Hike Notes: Parking is near the AMC Highland Center Lodge with a shuttle to the trailhead. See end of write up for additional information and logistics regarding this hike. Day 1 – 10.8 miles Mile 0.0 – The trail begins at the Webster /AT Trailhead (1300') on Route 302 about 4 miles from the AMC Highland Center. Head North to begin your climb to Mt Webster. This was some of the toughest 3 miles we have done with over 2600' of elevation gain before reaching Mt Webster. I don't remember any switchbacks! Mile 3.3 – Mt Webster summit (3910'), enjoy some great views of Crawford Notch. The Webster Jackson Trail (Webster Branch) comes in on the left, continue on the Webster Cliff Trail/AT. Mile 4.6 – Mt Jackson summit (4052'). -

Appalachia Winter/Spring 2019: Complete Issue

Appalachia Volume 70 Number 1 Winter/Spring 2019: Quests That Article 1 Wouldn't Let Go 2019 Appalachia Winter/Spring 2019: Complete Issue Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/appalachia Part of the Nonfiction Commons Recommended Citation (2019) "Appalachia Winter/Spring 2019: Complete Issue," Appalachia: Vol. 70 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/appalachia/vol70/iss1/1 This Complete Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Dartmouth Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Appalachia by an authorized editor of Dartmouth Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume LXX No. 1, Magazine No. 247 Winter/Spring 2019 Est. 1876 America’s Longest-Running Journal of Mountaineering & Conservation Appalachia Appalachian Mountain Club Boston, Massachusetts Appalachia_WS2019_FINAL_REV.indd 1 10/26/18 10:34 AM AMC MISSION Founded in 1876, the Appalachian Committee on Appalachia Mountain Club, a nonprofit organization with more than 150,000 members, Editor-in-Chief / Chair Christine Woodside advocates, and supporters, promotes the Alpina Editor Steven Jervis protection, enjoyment, and understanding Assistant Alpina Editor Michael Levy of the mountains, forests, waters, and trails of the Appalachian region. We believe these Poetry Editor Parkman Howe resources have intrinsic worth and also Book Review Editor Steve Fagin provide recreational opportunities, spiritual News and Notes Editor Sally Manikian renewal, and ecological and economic Accidents Editor Sandy Stott health for the region. Because successful conservation depends on active engagement Photography Editor Skip Weisenburger with the outdoors, we encourage people to Contributing Editors Douglass P. -

Guide to Crawford Notch State Park

Guide to Crawford Notch State Park On US Route 302 Harts Location, NH (12 miles NW of Bartlett) This 5,775 acre park provides access to numerous hiking trails, waterfalls, fishing, wildlife viewing, and spectacular mountain views. Crawford Notch State Park is rich in history with the famous Willey House. There are picnicking areas, parking for hiking, as well as scenic pull-offs and a visitor information center. Park History Discovery: In 1771 a Lancaster hunter, Timothy Nash, discovered what is now called Crawford Notch, while tracking a moose over Cherry Mountain. He noticed a gap in the distant mountains to the south and realized it was probably the route through the mountains mentioned in Native American lore. Packed with provisions, he worked his way through the notch and on to Portsmouth to tell Governor John Wentworth of his discovery. Doubtful a road could be built through the mountains, the governor made him a deal. If Nash could get a horse through from Lancaster he would grant him a large parcel of land at the head of the notch, with the condition he build a road to it from the east. Nash and his friend Benjamin Sawyer managed to trek through the notch with a very mellow farm horse, that at times, they were required to lower over boulders with ropes. The deal with the governor was kept and the road, at first not much more than a trail, was opened in 1775. Settlement: The Crawford family, the first permanent settlers in the area, exerted such a great influence on the development of the notch that the Great Notch came to be called Crawford Notch. -

White Mountains

CÝ Ij ?¨ AÛ ^_ A B C D E AúF G H I J K t S 4 . lm v 8 E A B E R L I N 7 B E R L I N n G I O N O D Se RR EE G I O N O Sl WEEKS STATE PARK E A T NN OO RR TT HH WW O O D SSUUCC CCEE SSSS 8 G R A T G R E G . LLAANN CCAA SSTT EE RR Ij 7 WHITE MOUNTAIN REGION N o l i r Dream Lake t a h Martin Meadow Pond KKIILLKK EE NNNNYY r T R T T l Ii d i NN a BICYCLE ROUTES Weeks Pond R OO l d Blood Pond a Judson Pond i M R M t M n M n o lt 1 I a e 1 d d RR D Weed Pond 4 N i 7 or R 3. th Rd . s Aÿ 8 Clark Pond y 3 EE e e . l 9 r d i A R-4 2 A a P .5 VV R Pond of Safety MOOSE BROOK STATE PARK 0 2.5 5 10 9 B 3. r fgIi e LEAD MINE STATE FOREST t J E F F E R S O N 19 Androscoggin River Aú s J E F F E R S O N US 2 5 a Mascot Pond Wheeler Pond 8 I Miles . I c 8 . Aè H n d P A-4 9 r R A N D O L P H a a R e R A N D O L P H Reflection Pond 4 r L s G O R H A M U . -

THE HOOT Volume 1 October 2017 the Trip of a Lifetime by Elizabeth Mcgowan

THE HOOT Volume 1 October 2017 The Trip Of A Lifetime By Elizabeth McGowan Timberlane gives many opportunities to students throughout the year. They give opportunities to go to shows, to get scholarships, and even to travel. This past summer one of these trips gave six Timberlane students the opportunity of a lifetime. On June 26th 2017, six Timberlane High School students and one chaperone boarded the airplane that brought them to Tanzania, Africa for 10 days, and these 10 days were days that they would never forget. However, the students preparation for this trip began long before June 26th. With a new country comes new diseases. In Tanzania there are many different diseases and viruses that you can contract that are very rare to get in the United States. For example, diseases and viruses such as malaria, hepatitis a, and typhoid are all much more common in Tanzania. Therefore, before going to Africa the students on the trip had to get the hepatitis a, and typhoid vac- cine, as well as take a malaria pill when they were on the trip. Tanzania, Africa is a very different place than the United States is. For example, in the United States you can rarely walk down the street without seeing someone in shorts, or a tight shirt. Howev- er, in Tanzania they are required to wear pants and it is looked down upon if you choose to wear tight clothing. Therefore, the students attending this trip packed solely pants, and loose shirts for the trip. TRHS Students Left to Right: Sam Valorose, Nate Alexander, Ryan Monahan, Julia Ramsdell, Story continued on Page 4 Caroline Diamond, and Hannah Sorenson An Exchange of Cultures A Freshman Adventure By Kayla Bowen By Maria Heim This years freshman are off with the sound of a horn! No, not the bells, the class trip to Adventurelore! Located in Danville, NH, the excursion took place in four waves of students from Monday, September 11th, to Thursday, September 14, 2017.