Intimate Ceremony: Ceramic Bath Accessories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2005, 21/06/2021 P`Kasana : Baart Sarkar Vyaapar Icanh Rijast/I Esa

Trade Marks Journal No: 2005, 21/06/2021 Reg. No. TECH/47-714/MBI/2000 Registered as News Paper p`kaSana : Baart sarkar vyaapar icanh rijasT/I esa.ema.raoD eMTa^p ihla ko pasa paosT Aa^ifsa ko pasa vaDalaa mauMba[- 400037 durBaaYa : 022 24101144 ,24101177 ,24148251 ,24112211. Published by: The Government of India, Office of The Trade Marks Registry, Baudhik Sampada Bhavan (I.P. Bhavan) Near Antop Hill, Head Post Office, S.M. Road, Mumbai-400037. Tel: 022 24101144, 24101177, 24148251, 24112211. 1 Trade Marks Journal No: 2005, 21/06/2021 Anauk/maiNaka INDEX AiQakairk saucanaaeM Official Notes vyaapar icanh rijasT/IkrNa kayaa-laya ka AiQakar xao~ Jurisdiction of Offices of the Trade Marks Registry sauiBannata ko baaro maoM rijaYT/ar kao p`arMiBak salaah AaoOr Kaoja ko ilayao inavaodna Preliminary advice by Registrar as to distinctiveness and request for search saMbaw icanh Associated Marks ivaraoQa Opposition ivaiQak p`maaNa p`~ iT.ema.46 pr AnauraoQa Legal Certificate/ Request on Form TM-46 k^apIra[T p`maaNa p`~ Copyright Certificate t%kala kaya- Operation Tatkal saava-jainak saucanaaeM Public Notices iva&aipt Aavaodna Applications advertised class-wise: 2 Trade Marks Journal No: 2005, 21/06/2021 vagavagavaga-vaga--- /// Class - 1 11-128 vagavagavaga-vaga--- /// Class - 2 129-167 vagavagavaga-vaga--- /// Class - 3 168-439 vagavagavaga-vaga--- /// Class - 4 440-472 vagavagavaga-vaga--- / Class - 5 473-1696 vagavagavaga-vaga--- /// Class - 6 1697-1790 vagavagavaga-vaga--- /// Class - 7 1791-1886 vagavagavaga-vaga--- /// Class - 8 1887-1923 -

Hideaway Spa Signature Treatments

HIDEAWAY SPA SIGNATURE TREATMENTS LOMI MASSAGE A beautiful massage ideal for island weather! This energizing treatment restores balance and harmony between the mind and body. You will be taken to a peaceful place to relieve stress and restore physical and mental being. 60 min, $120++ PAPAYA SCRUB Experience this tropical bliss using home grown papaya, rich in Vitamin E, Vitamin C and anti-oxidants. Great treatment to exfoliate from head to toe, leaving your skin glowing, soft and hydrated. 50 min, $100++ HIDEAWAY SPA HOLLISTIC TREATMENTS DORISSIMA D1-D7 SIGNATURE TREATMENTS 120MIN - $220++ D1 EMPOWERMENT RITUAL D5 CLEARING RITUAL Your journey begins with body brushing followed by Hot Stone You will be taken on a journey to greater clarity of mind.We begin massage. You will then be cocooned in body mask and receive by full body exfoliation followed by a body mask and purifying hot stones foot massage for total relaxation. facial leaving you feeling utterly relaxed. D2 UPLIFTING RITUAL D6 INSPIRING RITUAL Perfect treatment for those wanting to regain sense of joy and This treatment starts with an invigorating body scrub based happiness! The ritual begins with invigorating body brushing on the Ayuverdic philosophy. You will then receive full body followed by Ylang- Ylang, Orange & Lemongrass Therapy massage with warm oils that will bring your body into balance. Massage. You will then receive a stimulating scalp massage while While wrapped in softening body mask, heated sesame oil will be cocooned in Orange body mask. poured onto the third eye, bringing peace and clarity to the mind. D3 CONFIDENCE RITUAL D7 SPIRIT RITUAL This ritual starts with full body exfoliation using Honey and This ritual begins with a full body exfoliation to prepare you for Himalayan Salt leaving your skin radiant and glowing. -

Id Fda Cosmetic Talc Study 1973 Lewin

DEPARTMEr-.-T OF HEALTH, EDUCATION, AND WELFARE ~~~~~---. '.'.'.'.'.-.--' EMORANDUM PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE FOO D AJ" D DRUG ADMINISTRATION . 1--ic ZD .•• •••••.- ..- -~, : : : : . Dr. Robert M. Schaffner, Director July 31, 1973 ; .•~•. - ..•.•••••••....•-•. Office of Technology (BF-400) \ ' •... ~.,.• •••.••...•.•.- •. Dr. Alfred Weissler, Acting Director .•.•.':. ~ •.•••:.- ••.-•. :;. Division of Color Technology (BF-430) YECT: Summary and Comments on Prof. Lewin's Analytical Results for Asbestos in Talc .:.-.......•.•••-'- ....•.~ 1. The purposes of this memorandum are to present a summary of the analytical results for asbestos in Cosmetic talcum-type powders obtained by Prof. Seymour Z. Lewin of New York University in his role of consult ant to FDA; to compare his results with those obtained by other labora .:.•. •.": •.• .•••.•...•.. tories on some of the same samples; and to make some comments on the gen eral question of suitable techniques for the analysis of asbestos in talc. .•.•.• ...: ::.-: ::: 2. I asked Dr. Lewin in December 1971 to undertake asbestos analyses in 100 samples of cosmetic powders; the scope was expanded on two subsequent ::::::::::::; occasions, to include a total of 195 samples. I chose Dr. Lewin for this work because he is an internationally-recognized expert on mineralogical A::::::::: : :: chemistry and because he is a member of the academic community and there .••..•.•.•:: .. : ::. fore likely to be impartial in a confrontation between industry and government. Furthermore, his competence had previously been recognized : ::::::::: : by industry (by virtue of their own use. of him as a consultant) whi~h appeared to confer a desirable immunity against possible industry attacks ; ••:: :::_.:: : on the validity of the results. 3. Dr. Lewin's ·findings are shown in Table I; the key to the identities of the numbered samples is given in Table IV. -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1870, 08/10/2018

Trade Marks Journal No: 1870, 08/10/2018 Reg. No. TECH/47-714/MBI/2000 Registered as News Paper p`kaSana : Baart sarkar vyaapar icanh rijasT/I esa.ema.raoD eMTa^p ihla ko pasa paosT Aa^ifsa ko pasa vaDalaa mauMba[- 400037 durBaaYa : 022 24101144 ,24101177 ,24148251 ,24112211. fO@sa : 022 24140808 Published by: The Government of India, Office of The Trade Marks Registry, Baudhik Sampada Bhavan (I.P. Bhavan) Near Antop Hill, Head Post Office, S.M. Road, Mumbai-400037. Tel:022-24140808 1 Trade Marks Journal No: 1870, 08/10/2018 Anauk/maiNaka INDEX AiQakairk saucanaaeM Official Notes vyaapar icanh rijasT/IkrNa kayaa-laya ka AiQakar xao~ Jurisdiction of Offices of the Trade Marks Registry sauiBannata ko baaro maoM rijaYT/ar kao p`arMiBak salaah AaoOr Kaoja ko ilayao inavaodna Preliminary advice by Registrar as to distinctiveness and request for search saMbaw icanh Associated Marks ivaraoQa Opposition ivaiQak p`maaNa p`~ iT.ema.46 pr AnauraoQa Legal Certificate/ Request on Form TM-46 k^apIra[T p`maaNa p`~ Copyright Certificate t%kala kaya- Operation Tatkal saava-jainak saucanaaeM Public Notices iva&aipt Aavaodna Applications advertised class-wise: 2 Trade Marks Journal No: 1870, 08/10/2018 vaga- / Class - 1 11-142 vaga- / Class - 2 143-189 vaga- / Class - 3 190-522 vaga- / Class - 4 523-555 vaga- / Class - 5 556-1889 vaga- / Class - 6 1890-2045 vaga- / Class - 7 2046-2270 vaga- / Class - 8 2271-2312 vaga- / Class - 9 2313-2818 vaga- / Class - 10 2819-2905 vaga- / Class - 11 2906-3101 vaga- / Class - 12 3102-3196 vaga- / Class - 13 3197-3206 -

全文本) Acceptance for Registration (Full Version)

公報編號 Journal No.: 139 公布日期 Publication Date: 02-12-2005 分項名稱 Section Name: 接納註冊 (全文本) Acceptance for Registration (Full Version) 香港特別行政區政府知識產權署商標註冊處 Trade Marks Registry, Intellectual Property Department The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region 接納註冊 (全文本) 商標註冊處處長已根據《商標條例》(第 559 章)第 42 條,接納下列商標的註冊申請。現根據《商標條 例》第 43 條及《商標規則》(第 559 章附屬法例)第 15 條,公布申請的詳情。 根據《商標條例》第 44 條及《商標規則》第 16 條,任何人擬就下列商標的註冊提出反對,須在本公告 公布日期起計的三個月內,採用表格第 T6 號提交反對通知。(例如,若果公布日期爲 2003 年 4 月 4 日,則該三個月的最後一日爲 2003 年 7 月 3 日。)反對通知須載有反對理由的陳述及《商標規則》第 16(2)條所提述的事宜。反對人須在提交反對通知的同時,將該通知的副本送交有關申請人。 有關商標註冊處處長根據商標條例(第 43 章)第 13 條/商標條例(第 559 章)附表 5 第 10 條所接納的註冊申請, 請到 http://www.info.gov.hk/pd/egazette/檢視電子憲報。 ACCEPTANCE FOR REGISTRATION (FULL VERSION) The Registrar of Trade Marks has accepted the following trade marks for registration under section 42 of the Trade Marks Ordinance (Cap. 559). Under section 43 of the Trade Marks Ordinance and rule 15 of the Trade Marks Rules (Cap. 559 sub. leg.), the particulars of the applications are published. Under section 44 of the Trade Marks Ordinance and rule 16 of the Trade Marks Rules, any person who wishes to oppose the registration of any of these marks shall, within the 3-month period beginning on the date of this publication, file a notice of opposition on Form T6. (For example, if the publication date is 4 April 2003, the last day of the 3-month period is 3 July 2003.) The notice of opposition shall include a statement of the grounds of opposition and the matters referred to in rule 16(2). -

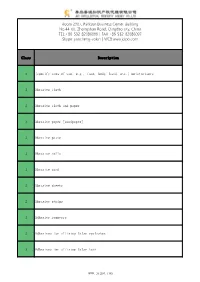

Class Description 3 {Specify Area of Use, E.G., Face, Body, Hand, Etc

Room 2907, Parkson Business Center Building No.44-60, Zhongshan Road, Qingdao city, China TEL:+86-532-82086099|FAX:+86-532-82086097 Skype: jiancheng-cokin|WEB:www.jcipo.com Class Description 3 {specify area of use, e.g., face, body, hand, etc.} moisturizers 3 Abrasive cloth 3 Abrasive cloth and paper 3 Abrasive paper [sandpaper] 3 Abrasive paste 3 Abrasive rolls 3 Abrasive sand 3 Abrasive sheets 3 Abrasive strips 3 Adhesive removers 3 Adhesives for affixing false eyelashes 3 Adhesives for affixing false hair www.jcipo.com 3 Adhesives for affixing false eyebrows 3 Adhesives for artificial nails 3 Adhesives for attaching artificial fingernails and/or eyelashes 3 Adhesives for cosmetic use 3 Adhesives for false eyelashes, hair and nails Aerosol spray for cleaning condenser coils of air filters for air conditioning, 3 heating and air filtration units 3 After shave lotions 3 After sun creams 3 After sun moisturisers 3 Aftershave 3 Aftershave cologne 3 Aftershave moisturising cream 3 Aftershave preparations 3 After-shave 3 After-shave balms www.jcipo.com 3 After-shave creams 3 After-shave emulsions 3 After-shave gel 3 After-shave liquid 3 After-shave lotions 3 After-sun gels [cosmetics] 3 After-sun lotions 3 After-sun milks [cosmetics] 3 After-sun oils [cosmetics] 3 Age retardant gel 3 Age retardant lotion 3 Age spot reducing creams 3 Air fragrancing preparations 3 Alcohol for cleaning purposes 3 All purpose cleaning preparations www.jcipo.com 3 All purpose cleaning preparation with deodorizing properties 3 All purpose cotton swabs for personal -

Memorandum Department of Health, Education, and \'\'Elfare Public He.\Lth Service Food and Drug Administration

MEMORANDUM DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION, AND \'\'ELFARE PUBLIC HE.\LTH SERVICE FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION TO Heinz J. Eiermann, (HFF-440) DATE: J anuary 7, 1976 Director, Division of Cosmetics THROUGH: Henry M. Davis, (HFF-446) Chief, Product Composition Branch FROM Ronald L. Yates, (HFF-446) Product Composition Branch SUBJECT: Tabulated Results of DCST's Analyses for Asbestos Minerals in Lewin, Field Activity Surveillance (FAS), Investigational and Consumer Cosmetic Talc Products. Attached are a series of tables summarizing data obtained from the DCST analyses of cosmetic talc products for asbestos minerals. Also included, for purposes of comparison, are Dr. S. z. Lewin's analytical data obtained by x-ray diffractometry. Attachments: a. Master table . 11 Summary Table of Results of the Investigations of Commercial Cosmetic Talc Products For Asbestos Minerals by S. Z. Lewin and the Division of This table contains analytical data of all the Lewin samples analyzed by DCST. Included is Lewin's data on these samples. b. Table I. "Summary of Results of DCST' s Analyses For Asbestos Minerals in Talc Samples Reported by Lewin to contain Tremolite and/or Chrysotile. 11 Information in this table was extracted from the master table and lists only those samples which Lewin the presence of asbestos minerals. )' c. Table II. "Cosmetic Tales Analyzed by Lewin and Reported to Contain Chrysotile and/or Tremolite which were not Analyzed tf by DCST by Either DTA or Optical Microscopy." DCST does not possess the samples listed in this table and, therefore, were unable to analyze them. d. Table III. "Summary of DCST' s Analyses of Cosmetic Talc Products by Differential Thermal Analysis (DTA) and Optical Micr oscopy. -

Notice of Opposition Opposer Information Applicant

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA273364 Filing date: 03/20/2009 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Notice of Opposition Notice is hereby given that the following party opposes registration of the indicated application. Opposer Information Name The Sunrider Corporation, dba Sunrider I Granted to Date 03/22/2009 of previous extension Address 1625 Abalone Avenue Torrance, CA 90501 UNITED STATES Party who filed The Sunrider Corporation, dba Sunrider International Extension of time THE SUNRIDER CORPORATION, DBA SUNRIDER INTERNATIONAL to oppose Relationship to The Opposer's name is The Sunrider Corporation, dba Sunrider International. party who filed Due to lack of space on a previous page, the name of Opposer was abbreviated Extension of time to "The Sunrider Corporation, dba Sunrider I" with the "I" being the first letter of to oppose the word "International." Attorney Elizabeth A. Linford information Ladas & Parry LLP 5670 Wilshire Boulevard Suite 2100 Los Angeles, CA 90036 UNITED STATES [email protected] Phone:3239342300 Applicant Information Application No 77311353 Publication date 09/23/2008 Opposition Filing 03/20/2009 Opposition 03/22/2009 Date Period Ends Applicant Beauty Pearls for Chemo Girls, LLC 6 Orchard Drive South Salem, NY 10590 UNITED STATES Goods/Services Affected by Opposition Class 003. All goods and services in the class are opposed, namely: ADHESIVES FOR AFFIXING FALSE EYELASHES; ADHESIVES -

Thai Hien Taiteit Van Van Al Tidak Mat on T He

THAI HIEN TAITEIT US009737467B2VAN VAN AL TIDAK MAT ON T HE (12 ) United States Patent (10 ) Patent No. : US 9 , 737 , 467 B2 Hara et al. ( 45) Date of Patent : Aug . 22 , 2017 ( 54 ) BODY ODOR SUPPRESSING AGENT 2007/ 0017453 AL 1 / 2007 Fritter et al . 2008 /0194447 AL 8 / 2008 Oki (71 ) Applicant: MANDOM CORPORATION , Osaka, 2012/ 0258853 Al 10 / 2012 Veeraraghavan et al . Osaka ( JP ) FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (72 ) Inventors : Takeshi Hara , Osaka ( JP ); Hironori 101090742 A 12 / 2007 Shimizu , Osaka ( JP ) 0 411 206 Al 2 / 1991 2 - 224761 A 9 / 1990 ( 73) Assignee : MANDOM CORPORATION , Osaka 4 - 256436 A 9 / 1992 8 - 208211 A 8 / 1996 ( JP ) 9 - 234364 A 9 / 1997 2002 - 145747 A 5 / 2002 ( * ) Notice : Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 2005 - 263610 A 9 / 2005 patent is extended or adjusted under 35 2009 - 209043 A 9 / 2009 U . S . C . 154 (b ) by 0 days. 2011 - 148785 A 8 / 2011 JP 2014 - 516903 A 7 / 2014 (21 ) Appl. No. : 15 / 346 ,698 WO WO - 2006 / 071318 Al 7 / 2006 ( 22 ) Filed : Nov . 8 , 2016 OTHER PUBLICATIONS (65 ) Prior Publication Data International Search Report for the Application No . PCT / JP2013 / 082619 mailed Mar . 4 , 2014 . US 2017 /0049672 A1 Feb . 23 , 2017 ( Edited by ) Mitsui, Takeo , “ New Cosmetic Science ( Shin Keshouhingaku ) ” , Nanzando Co ., Ltd . , 2001 , second edition , pp . 510 - 515 . Related U . S . Application Data Wu , Jufang , “ Modeling adsorption of organic compounds on acti vated carbon ” 2004 , printed in Sweden , pp . 1 -74 (see p . 7 ) . (63 ) Continuation of application No . -

1001 Everyday Makeup Tips?

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 5 What In The World Am I Talking About, And Why Should You Invest Your Time To Keep Reading?..... 5 Have You Ever Experienced This? (I Like To Call It The ‘Beauty Bummer’!) ........................................... 6 Why Failure Is NOT Your Fault 90% Of The Time!................................................................................... 6 NO! Of Course Not! ................................................................................................................................... 7 And Now, “The Rest of The Story”…......................................................................................................... 7 You Are Left With 3 Options:..................................................................................................................... 8 The Beauty Bummer In Hiding…............................................................................................................... 9 You Are Being Given An Incomplete System!........................................................................................... 9 Here Is The Life of A Typical Online Product In The beauty Marketplace. ............................................... 9 But Let’s Get Real…................................................................................................................................10 THE PURPOSE OF THIS REPORT… ......................................................................... -

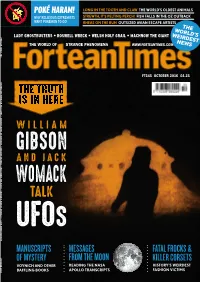

Womack and Gibson the Truth Is in Here

POKÉ HARAM! LONG IN THE TOOTH AND CLAW THE WORLD'S OLDEST ANIMALS WHY RELIGIOUS EXTREMISTS STREWTH, IT'S PELTING PERCH! FISH FALLS IN THE OZ OUTBACK WANT POKÉMON TO GO! RHEAS ON THE RUN OUTSIZED AVIAN ESCAPE ARTISTS THE WOR THE WORLD OF STRANGE PHENOMENA LD’S LADY GHOSTBUSTERS • ROSWELL WRECK • WELSH HOLY GRAIL • MACHNOWWWW.FORTEANTIMES.COM THE GIANT WEIRDES FORTEAN TIMES 345 NEWS T THE WORLD OF STRANGE PHENOMENA WWW.FORTEANTIMES.COM FT345 OCTOBER 2016 £4.25 GIBSON AND WOMACK TALK UFOS • MANUSCRIPTS OF MYSTERY • THE TRUTH IS IN HERE WILLIAM FA GIBSON SHION VICTIMS • MACHNOW THE GIANT • WORLD'S OLDEST ANIMALS • LADY GHOSTBUSTERS AND JACK WOMACK TALK UFOS MANUSCRIPTS MESSAGES FATALFROCKS& OCTOBER 2016 OFMYSTERY FROMTHEMOON KILLERCORSETS VOYNICH AND OTHER READING THE NASA HISTORY'S WEIRDEST BAFFLING BOOKS APOLLO TRANSCRIPTS FASHION VICTIMS LISTEN IT JUST MIGHT CHANGE YOUR LIFE LIVE | CATCH UP | ON DEMAND Fortean Times 345 strange days Pokémon versus religion, world’s oldest creatures, fate of Flight MH370, rheas on the run, Bedfordshire big cat, female ghostbusters, Australian fi sh fall, Apollo transcripts, avian CONTENTS drones, pornographer’s papyrus – and much more. 05 THE CONSPIRASPHERE 23 MYTHCONCEPTIONS 14 ARCHAEOLOGY 25 ALIEN ZOO the world of strange phenomena 15 CLASSICAL CORNER 28 NECROLOG 16 SCIENCE 29 FAIRIES & FORTEANA 18 GHOSTWATCH 30 THE UFO FILES features COVER STORY 32 FROM OUTER SPACE TO YOU JACK WOMACK has been assembling his collection of UFO-related books for half a century, gradually building up a visual and cultural history of the saucer age. Fellow writer and fortean WILLIAM GIBSON joined him to celebrate a shared obsession with pulp ufology, printed forteana and the search for an all too human truth.. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,779,686 B2 Bartholomew Et Al

USOO67796.86B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,779,686 B2 Bartholomew et al. (45) Date of Patent: Aug. 24, 2004 (54) POINT-OF-SALE BODY POWDER 4,561,850 A 12/1985 Fabbri et al. DSPENSING SYSTEM 4,681,546 A 7/1987 Hart 4,705,083 A 11/1987 Rossetti (75) Inventors: Julie R. Bartholomew, Birmingham, 4,764.044 A 8/1988 Konose 4,830,218 A 5/1989 Shirkhan MI (US); Charles P. Hines, Jr., 4,846,184 A 7/1989 Comment et al. Hamburg, MI (US) 4,871,262 A 10/1989 Krauss et al. 4,887,410 A 12/1989 Gandini (73) Assignee: IMX Labs, Inc., Birmingham, MI (US) D306,808 S 3/1990 Thomas 4909,632 A 3/1990 Simpson (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 4,953.985 A 9/1990 Miller patent is extended or adjusted under 35 4,966.205 A 10/1990 Tanaka U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. 4,967,938 A 11/1990 Hellenberg (21) Appl. No.: 10/437,085 (List continued on next page.) FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (22) Filed: May 13, 2003 DE 41 10299 C1 2/1993 (65) Prior Publication Data EP O 443 741 B1 8/1991 US 2003/0230355 A1 Dec. 18, 2003 EP O 446 512 B1 1/1995 (List continued on next page.) Related U.S. Application Data OTHER PUBLICATIONS (63) Continuation of application No. 10/151,398, filed on May 20, 2002, which is a continuation of application No. 09/872, Information from www.reflect.com.