Redalyc.TAPHONOMIC ANALYSIS of RODENT BONES from Lontra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mitochondrial Genomes of the United States Distribution

fevo-09-666800 June 2, 2021 Time: 17:52 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 08 June 2021 doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.666800 Mitochondrial Genomes of the United States Distribution of Gray Fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) Reveal a Major Phylogeographic Break at the Great Plains Suture Zone Edited by: Fernando Marques Quintela, Dawn M. Reding1*, Susette Castañeda-Rico2,3,4, Sabrina Shirazi2†, Taxa Mundi Institute, Brazil Courtney A. Hofman2†, Imogene A. Cancellare5, Stacey L. Lance6, Jeff Beringer7, 8 2,3 Reviewed by: William R. Clark and Jesus E. Maldonado Terrence C. Demos, 1 Department of Biology, Luther College, Decorah, IA, United States, 2 Center for Conservation Genomics, Smithsonian Field Museum of Natural History, Conservation Biology Institute, National Zoological Park, Washington, DC, United States, 3 Department of Biology, George United States Mason University, Fairfax, VA, United States, 4 Smithsonian-Mason School of Conservation, Front Royal, VA, United States, Ligia Tchaicka, 5 Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology, University of Delaware, Newark, DE, United States, 6 Savannah River State University of Maranhão, Brazil Ecology Laboratory, University of Georgia, Aiken, SC, United States, 7 Missouri Department of Conservation, Columbia, MO, *Correspondence: United States, 8 Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Organismal Biology, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, United States Dawn M. Reding [email protected] We examined phylogeographic structure in gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) across † Present address: Sabrina Shirazi, the United States to identify the location of secondary contact zone(s) between eastern Department of Ecology and and western lineages and investigate the possibility of additional cryptic intraspecific Evolutionary Biology, University of California Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, divergences. -

Regional Differences in Wild North American River Otter (Lontra Canadensis) Behavior and Communication

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 2020 Regional Differences in Wild North American River Otter (Lontra canadensis) Behavior and Communication Sarah Walkley Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Biological Psychology Commons, Cognitive Psychology Commons, Comparative Psychology Commons, Integrative Biology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Walkley, Sarah, "Regional Differences in Wild North American River Otter (Lontra canadensis) Behavior and Communication" (2020). Dissertations. 1752. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1752 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REGIONAL DIFFERENCES IN WILD NORTH AMERICAN RIVER OTTER (LONTRA CANADENSIS) BEHAVIOR AND COMMUNICATION by Sarah N. Walkley A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Education and Human Sciences and the School of Psychology at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved by: Dr. Hans Stadthagen, Committee Chair Dr. Heidi Lyn Dr. Richard Mohn Dr. Carla Almonte ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Hans Stadthagen Dr. Sara Jordan Dr. Karen S. Coats Committee Chair Director of School Dean of the Graduate School May 2020 COPYRIGHT BY Sarah N. Walkley 2020 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT This study focuses on the vocalization repertoires of wild North American river otters (Lontra canadensis) in New York and California. Although they are the same species, these two established populations of river otters are separated by a significant distance and are distinct from one another. -

The 2008 IUCN Red Listings of the World's Small Carnivores

The 2008 IUCN red listings of the world’s small carnivores Jan SCHIPPER¹*, Michael HOFFMANN¹, J. W. DUCKWORTH² and James CONROY³ Abstract The global conservation status of all the world’s mammals was assessed for the 2008 IUCN Red List. Of the 165 species of small carni- vores recognised during the process, two are Extinct (EX), one is Critically Endangered (CR), ten are Endangered (EN), 22 Vulnerable (VU), ten Near Threatened (NT), 15 Data Deficient (DD) and 105 Least Concern. Thus, 22% of the species for which a category was assigned other than DD were assessed as threatened (i.e. CR, EN or VU), as against 25% for mammals as a whole. Among otters, seven (58%) of the 12 species for which a category was assigned were identified as threatened. This reflects their attachment to rivers and other waterbodies, and heavy trade-driven hunting. The IUCN Red List species accounts are living documents to be updated annually, and further information to refine listings is welcome. Keywords: conservation status, Critically Endangered, Data Deficient, Endangered, Extinct, global threat listing, Least Concern, Near Threatened, Vulnerable Introduction dae (skunks and stink-badgers; 12), Mustelidae (weasels, martens, otters, badgers and allies; 59), Nandiniidae (African Palm-civet The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species is the most authorita- Nandinia binotata; one), Prionodontidae ([Asian] linsangs; two), tive resource currently available on the conservation status of the Procyonidae (raccoons, coatis and allies; 14), and Viverridae (civ- world’s biodiversity. In recent years, the overall number of spe- ets, including oyans [= ‘African linsangs’]; 33). The data reported cies included on the IUCN Red List has grown rapidly, largely as on herein are freely and publicly available via the 2008 IUCN Red a result of ongoing global assessment initiatives that have helped List website (www.iucnredlist.org/mammals). -

Diversity of Mammals and Birds Recorded with Camera-Traps in the Paraguayan Humid Chaco

Bol. Mus. Nac. Hist. Nat. Parag. Vol. 24, nº 1 (Jul. 2020): 5-14100-100 Diversity of mammals and birds recorded with camera-traps in the Paraguayan Humid Chaco Diversidad de mamíferos y aves registrados con cámaras trampa en el Chaco Húmedo Paraguayo Andrea Caballero-Gini1,2,4, Diego Bueno-Villafañe1,2, Rafaela Laino1 & Karim Musálem1,3 1 Fundación Manuel Gondra, San José 365, Asunción, Paraguay. 2 Instituto de Investigación Biológica del Paraguay, Del Escudo 1607, Asunción, Paraguay. 3 WWF. Bernardino Caballero 191, Asunción, Paraguay. 4Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract.- Despite its vast extension and the rich fauna that it hosts, the Paraguayan Humid Chaco is one of the least studied ecoregions in the country. In this study, we provide a list of birds and medium-sized and large mammals recorded with camera traps in Estancia Playada, a private property located south of Occidental region in the Humid Chaco ecoregion of Paraguay. The survey was carried out from November 2016 to April 2017 with a total effort of 485 camera-days. We recorded 15 mammal and 20 bird species, among them the bare-faced curassow (Crax fasciolata), the giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla), and the neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis); species that are globally threatened in different dregrees. Our results suggest that Estancia Playada is a site with the potential for the conservation of birds and mammals in the Humid Chaco of Paraguay. Keywords: Species inventory, Mammals, Birds, Cerrito, Presidente Hayes. Resumen.- A pesar de su vasta extensión y la rica fauna que alberga, el Chaco Húmedo es una de las ecorregiones menos estudiadas en el país. -

Food Habits of the North American River Otter (Lontra Canadensis)

Food Habits of the North American River Otter (Lontra canadensis) Heidi Hansen Graduate Program, Department of Zoology and Physiology University of Wyoming 2003 Introduction The North American river otter (Lontra canadensis) is a predator adapted to hunting in water, feeding on aquatic and semi-aquatic animals. The vulnerability and seasonal availability of prey animals primarily determines the food habits and prey preference of the river otter (Erlinge 1968; Melquist and Hornocker 1983). There are many studies that document the food habits of the river otter for most of their present range in North America. Among many, a few areas of study include southeastern Alaska (Larsen 1984); Arkansas (Tumlison and Karnes 1987); northeastern Alberta, Canada (Reid et al. 1994); Colorado (Berg 1999); Idaho (Melquist and Hornocker 1983); Minnesota (Route and Peterson 1988); Oregon (Toweill 1974); and Pennsylvania (Serfass et al. 1990). The diet of the river otter has been determined by analyzing either scat collected in the field (Berg 1999; Larsen 1984; Reid et al. 1994; Serfass et al. 1990; Tumlison and Karnes 1987) or gut contents obtained from trapper-caught otters (Toweill 1974). The contents were identified to family (fish, crustacean, etc.) and species if possible in order to determine the prey selection and the frequency of occurrence in the diet of the river otter. Fish are the most important prey items for river otters, occurring in the diet throughout the year (Larsen 1984; Reid et al. 1994; Route and Peterson 1988; Serfass et al. 1990, Toweill 1974, Tumlison and Karnes 1987). This has been documented by every study done on river otter food habits. -

Evolutionary History of Carnivora (Mammalia, Laurasiatheria) Inferred

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.05.326090; this version posted October 5, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. This article is a US Government work. It is not subject to copyright under 17 USC 105 and is also made available for use under a CC0 license. 1 Manuscript for review in PLOS One 2 3 Evolutionary history of Carnivora (Mammalia, Laurasiatheria) inferred 4 from mitochondrial genomes 5 6 Alexandre Hassanin1*, Géraldine Véron1, Anne Ropiquet2, Bettine Jansen van Vuuren3, 7 Alexis Lécu4, Steven M. Goodman5, Jibran Haider1,6,7, Trung Thanh Nguyen1 8 9 1 Institut de Systématique, Évolution, Biodiversité (ISYEB), Sorbonne Université, 10 MNHN, CNRS, EPHE, UA, Paris. 11 12 2 Department of Natural Sciences, Faculty of Science and Technology, Middlesex University, 13 United Kingdom. 14 15 3 Centre for Ecological Genomics and Wildlife Conservation, Department of Zoology, 16 University of Johannesburg, South Africa. 17 18 4 Parc zoologique de Paris, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris. 19 20 5 Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL, USA. 21 22 6 Department of Wildlife Management, Pir Mehr Ali Shah, Arid Agriculture University 23 Rawalpindi, Pakistan. 24 25 7 Forest Parks & Wildlife Department Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. 26 27 28 * Corresponding author. E-mail address: [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.05.326090; this version posted October 5, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. This article is a US Government work. -

Mercury Poisoning in a Free-Living Northern River Otter (Lontra Canadensis)

Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 46(3), 2010, pp. 1035–1039 # Wildlife Disease Association 2010 Mercury Poisoning in a Free-Living Northern River Otter (Lontra canadensis) Jonathan M. Sleeman,1,5,6 Daniel A. Cristol,2 Ariel E. White,2 David C. Evers,3 R. W. Gerhold,4 and Michael K. Keel41Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Richmond, Virginia 23230, USA; 2 Department of Biology, The College of William & Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia 23187, USA; 3 BioDiversity Research Institute, Gorham, Maine 04038, USA; 4 Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study, College of Veterinary Medicine, The University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602, USA; 5 Current address: USGS National Wildlife Health Center, 6006 Schroeder Road, Madison, Wisconsin 53711, USA; 6 Corresponding author (email: [email protected]) ABSTRACT: A moribund 5-year-old female increasing (Basu et al., 2007; Wolfe et al., northern river otter (Lontra canadensis) was 2007). Background levels of mercury in found on the bank of a river known to be otters in ecosystems contaminated primar- extensively contaminated with mercury. It exhibited severe ataxia and scleral injection, ily through atmospheric deposition are made no attempt to flee, and died shortly under 9.0 mg/g (wet weight [ww]) in the thereafter of drowning. Tissue mercury levels liver (Yates et al., 2005) and lower in the were among the highest ever reported for a kidney (Kucera, 1983). Levels of mercury free-living terrestrial mammal: kidney, 353 mg/ g; liver, 221 mg/g; muscle, 121 mg/g; brain (three in ecosystems contaminated with point replicates from cerebellum), 142, 151, 151 mg/g sources can result in mortalities, as (all dry weights); and fur, 183 ug/g (fresh reported for a dead otter from Ontario weight). -

Os Nomes Galegos Dos Carnívoros 2019 2ª Ed

Os nomes galegos dos carnívoros 2019 2ª ed. Citación recomendada / Recommended citation: A Chave (20192): Os nomes galegos dos carnívoros. Xinzo de Limia (Ourense): A Chave. https://www.achave.ga"/wp#content/up"oads/achave_osnomes!a"egosdos$carnivoros$2019.pd% Fotografía: lince euroasiático (Lynx lynx ). Autor: Jordi Bas. &sta o'ra est( su)eita a unha licenza Creative Commons de uso a'erto* con reco+ecemento da autor,a e sen o'ra derivada nin usos comerciais. -esumo da licenza: https://creativecommons.or!/"icences/'.#n #nd//.0/deed.!". Licenza comp"eta: https://creativecommons.or!/"icences/'.#n #nd//.0/"e!a"code0"an!ua!es. 1 Notas introdutorias O que cont n este documento Neste documento fornécense denominacións galegas para diferentes especies de mamíferos carnívoros. Primeira edición (2018): En total! ac"éganse nomes para 2#$ especies! %&ue son practicamente todos os carnívoros &ue "ai no mundo! salvante os nomes das focas% e $0 subespecies. Os nomes galegos das focas expóñense noutro recurso léxico da +"ave dedicado só aos nomes das focas! manatís e dugongos. ,egunda edición (201-): +orríxese algunha gralla! reescrí'ense as notas introdutorias e incorpórase o logo da +"ave ao deseño do documento. A estrutura En primeiro lugar preséntase a clasificación taxonómica das familias de mamíferos carnívoros! onde se apunta! de maneira xeral! os nomes dos carnívoros &ue "ai en cada familia. seguir vén o corpo do documento! unha listaxe onde se indica! especie por especie, alén do nome científico! os nomes galegos e ingleses dos diferentes mamíferos carnívoros (nalgún caso! tamén, o nome xenérico para un grupo deles ou o nome particular dalgunhas subespecies). -

Northern River Otter, Lontra Canadensis

Lontra canadensis (Schreber, 1777) Margaret K. Trani and Brian R. Chapman CONTENT AND TAXONOMIC COMMENTS The Nearctic northern river otter was recognized as distinct from Eurasian genera by van Zyll de Jong (1972, 1987). Wozencraft (1993) and Baker et al. (2003) followed van Zyll de Jong in using Lontra as the generic name. However, some authors (e.g., Whitaker and Hamilton 1998) continue to place the species in genus Lutra. Seven subspecies currently are recog- nized (Hall 1981, Lariviere and Walton 1998); one subspecies (L. c. lataxina) occurs in the South. The life history of the northern river otter is reviewed by Toweill and Tabor (1982), Melquist and Dronkert (1987), Lariviere and Walton (1998), and Melquist et al. (2003). DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS The northern river otter has a large, long body with short legs and a hydrodynamic shape that distin- guishes it from other mustelids. Feet are pentadactyl and plantigrade with interdigital webbing pronounced on the longer toes of the hind foot (Melquist et al. 2003). The tail is about one-third of total length and tapered from base to tip. Measurements are: total length, 890–1200 mm; tail, 350–520 mm; hind foot, 100–140 mm; ear, 20–30 mm; weight, 4.5–15 kg. Females are 3–21% smaller than males (Blundell et al. 2002). The short, thick, and glossy pelage ranges from dark brown to dark reddish-brown dorsally, and pale brown to silver-gray ventrally. The throat and muzzle often are silvery gray to brownish-white. The ears are round and inconspicuous. The small eyes are positioned anteriorly (Lariviere and Walton 1998). -

Mammals of New York State – Efb 483

MAMMALS OF NEW YORK STATE – EFB 483 ORDER DIDELPHIMORPHIA Family: Didelphidae 1. Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana) ORDER SORICOMORPHA Family Soricidae 2. Masked shrew (Sorex cinereus) 3. Pygmy shrew (Sorex hoyi) 4. Long-tailed shrew (Sorex dispar) 5. Smoky shrew (Sorex fumeus) 6. Water shrew (Sorex palustris) 7. Northern short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda) 8. Least shrew (Cryptotis parva) Family Talpidae 9. Eastern mole (Scalopus aquaticus) 10. Hairy-tailed mole (Parascalops breweri) 11. Star-nosed mole (Condylura cristata) ORDER CHIROPTERA Family: Vespertilionidae 12. Little brown myotis (Myotis lucifugus) 13. Northern myotis (Myotis septrionalis) 14. Indiana myotis (Myotis sodalis) 15. Small-footed myotis (Myotis leibii) 16. Eastern red bat (Lasiurus borealis) 17. Hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus) 18. Big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus) 19. Eastern pipistrellus (Pipistrellus (Perimyotis) subflavus) 20. Silver-haired bat (Lasionycteris noctivagans) ORDER CARNIVORA Family: Canidae 21. Coyote (Canis latrans) 22. Red fox (Vulpes vulpes) 23. Gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) Family: Ursidae 24. American black bear (Ursus americanus) Family: Procyonidae 25. Raccoon (Procyon lotor) Family: Mustelidae 26. Fisher (Martes pennanti) 27. American marten (Martes americana) 28. Mink (Neovison vison) 29. Long-tailed weasel (Mustela frenata) 30. Short-tailed weasel (Mustela erminea) 31. River otter (Lontra canadensis) Family: Mephitidae 32. Striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis) Family: Felidae 33. Bobcat (Lynx rufus) ORDER ARTIODACTYL Family: Cervidae 34. White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) 35. Moose (Alces alces) ORDER RODENTIA Family: Sciuridae 36. Red squirrel: (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) 37. Eastern gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) 38. Fox squirrel (Sciurus niger) 39. Northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus) 40. Southern flying squirrel (Glaucomys volans) 41. Eastern chipmunk (Tamias striatus) 42. -

Effects of Increased Feeding Frequency on Captive North American River Otter (Lontra Canadensis) Behavior

EFFECTS OF INCREASED FEEDING FREQUENCY ON CAPTIVE NORTH AMERICAN RIVER OTTER (LONTRA CANADENSIS) BEHAVIOR By Matthew J. Hasenjager A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE ZOO AND AQUARIUM MANAGEMENT 2011 ABSTRACT EFFECTS OF INCREASED FEEDING FREQUENCY ON CAPTIVE NORTH AMERICAN RIVER OTTER (LONTRA CANADENSIS) BEHAVIOR By Matthew J. Hasenjager Manipulating captive feedings to resemble natural conditions can be highly effective in promoting species-typical foraging behaviors and patterns, thereby improving welfare. Despite its potential importance and relative ease of implementation, meal frequency is rarely considered in captive management strategies. North American river otters (Lontra canadensis) are a common species in North American zoos and provide an excellent subject to investigate feeding frequency questions. Wild otters spend large amounts of time foraging and consuming numerous small meals daily. Higher activity levels might be associated with increased meal frequency and decreased resting behavior in captivity. In this study, behavioral responses to a number of factors were considered. While no behavioral responses to meal frequency were detected, other feeding- related variables could have obscured potential effects. Additional variables were found to significantly affect behavior. The time of day appeared to influence behavior via external factors, such as the zoo-going public which was associated with decreased resting and increased stereotypic behavior. Precipitation could provide unplanned, beneficial stimulation for amphibious animals such as otters. Finally, individual behavioral variation was used to aid interpretation and highlight the importance of accounting for animal individuality. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the administration and keepers at Potter Park Zoo and John Ball Zoo for allowing and facilitating this study. -

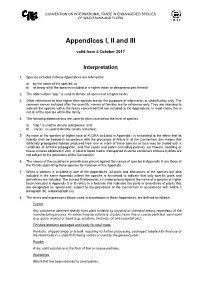

Appendices I, II and III (Valid from 4 October 2017)

CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA Appendices I, II and III valid from 4 October 2017 Interpretation 1. Species included in these Appendices are referred to: a) by the name of the species; or b) as being all of the species included in a higher taxon or designated part thereof. 2. The abbreviation “spp.” is used to denote all species of a higher taxon. 3. Other references to taxa higher than species are for the purposes of information or classification only. The common names included after the scientific names of families are for reference only. They are intended to indicate the species within the family concerned that are included in the Appendices. In most cases this is not all of the species within the family. 4. The following abbreviations are used for plant taxa below the level of species: a) “ssp.” is used to denote subspecies; and b) “var(s).” is used to denote variety (varieties). 5. As none of the species or higher taxa of FLORA included in Appendix I is annotated to the effect that its hybrids shall be treated in accordance with the provisions of Article III of the Convention, this means that artificially propagated hybrids produced from one or more of these species or taxa may be traded with a certificate of artificial propagation, and that seeds and pollen (including pollinia), cut flowers, seedling or tissue cultures obtained in vitro, in solid or liquid media, transported in sterile containers of these hybrids are not subject to the provisions of the Convention.