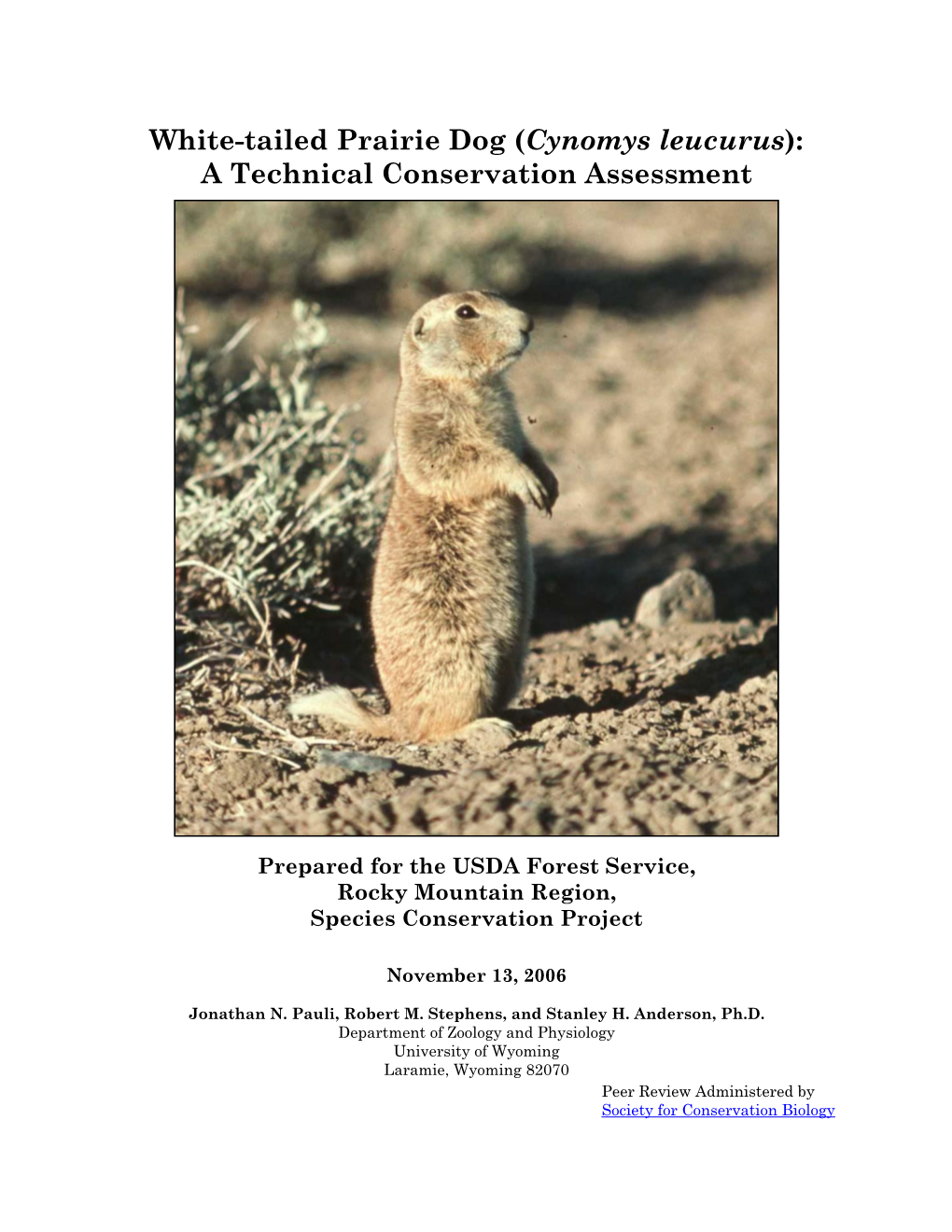

White-Tailed Prairie Dog (Cynomys Leucurus): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plant Guide for Fourwing Saltbush (Atriplex Canescens)

Plant Guide saline-sodic soils (Ogle and St. John, 2008). It has FOURWING SALTBUSH excellent drought tolerance and has been planted in highway medians and on road shoulders, slopes, and other Atriplex canescens (Pursh) Nutt. disturbed areas near roadways. Because it is a good Plant Symbol = ATCA2 wildlife browse species, caution is recommended in using fourwing saltbush in plantings along roadways. Its Contributed by: USDA NRCS Idaho Plant Materials extensive root system provides excellent erosion control. Program Reclamation: fourwing saltbush is used extensively for reclamation of disturbed sites (mine lands, drill pads, exploration holes, etc,). It provides excellent species diversity for mine land reclamation projects. Status Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g., threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values). Description Fourwing saltbush is a polymorphic species varying from deciduous to evergreen, depending on climate. Its much- branched stems are stout with whitish bark. Mature plants range from 0.3 to 2.4 m (1 to 8 ft) in height, depending on ecotype and the soil and climate. Its leaves are simple, alternate, entire, linear-spatulate to narrowly oblong, Fourwing saltbush. Photo by Steven Perkins @ USDA-NRCS canescent (covered with fine whitish hairs) and ½ to 2 PLANTS Database inches long. Its root system is branched and commonly very deep reaching depths of up to 6 m (20 ft) when soil Alternate Names depth allows (Kearney et al., 1960). Common Alternate Names: Fourwing saltbush is mostly dioecious, with male and Chamise, chamize, chamiso, white greasewood, saltsage, female flowers on separate plants (Welsh et al., 2003); fourwing shadscale, bushy atriplex however, some monoecious plants may be found within a population. -

Plant Guide for Yellow Rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus Viscidiflorus)

Plant Guide valuable forage especially during late fall and early winter YELLOW after more desirable forage has been utilized (Tirmenstein, 1999). Palatability and usage vary between RABBITBRUSH subspecies of yellow rabbitbrush (McArthuer et al., 1979). Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus (Hook.) Nutt. Yellow rabbitbrush provides cover and nesting habitat for Plant Symbol = CHVI8 sage-grouse, small birds and rodents (Gregg et al., 1994). Black-tailed jackrabbits consume large quantities of Contributed by: USDA NRCS Idaho Plant Materials yellow rabbitbrush during winter and early spring when Program plants are dormant (Curie and Goodwin, 1966). Yellow rabbitbrush provides late summer and fall forage for butterflies. Unpublished field reports indicate visitation from bordered patch butterflies (Chlosyne lacinia), Mormon metalmark (Apodemia mormo), mourning cloak (Nymphalis antiopa), common checkered skipper (Pyrgus communis), and Weidemeyer’s admiral (Limenitis weidemeyerii). Restoration: Yellow rabbitbrush is a seral species which colonizes disturbed areas making it well suited for use in restoration and revegetation plantings. It can be established from direct seeding and will spread via windborne seed. It has been successfully used for revegetating depleted rangelands, strip mines and roadsides (Plummer, 1977). Status Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g., threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values). Description General: Sunflower family (Asteraceae). Yellow rabbitbrush is a low- to moderate-growing shrub reaching mature heights of 20 to 100 cm (8 to 39 in) tall. The stems Al Schneider @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database can be glabrous or pubescent depending on variety, and are covered with pale green to white-gray bark. -

Infection in Kangaroo Rats (Dipodomys Spp.): Effects on Digestive Efficiency

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 55 Number 1 Article 8 1-16-1995 Whipworm (Trichuris dipodomys) infection in kangaroo rats (Dipodomys spp.): effects on digestive efficiency James C. Munger Boise State University, Boise, idaho Todd A. Slichter Boise State University, Boise, Idaho Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Munger, James C. and Slichter, Todd A. (1995) "Whipworm (Trichuris dipodomys) infection in kangaroo rats (Dipodomys spp.): effects on digestive efficiency," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 55 : No. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol55/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Great Basin Naturalist 55(1), © 1995, pp. 74-77 WHIPWORM (TRICHURIS DIPODOMYS) INFECTION IN KANGAROO RATS (DIPODOMYS SPP): EFFECTS ON DIGESTIVE EFFICIENCY James C. Mungerl and Todd A. Slichterl ABSTRACT.-To dcterminc whether infections by whipworms (Trichuris dipodumys [Nematoda: Trichurata: Trichuridae]) might affect digestive eHlciency and therefore enel"/,,'Y budgets of two species ofkangaroo rats (Dipodomys microps and Dipodumys urdU [Rodentia: Heteromyidae]), we compared the apparent dry matter digestibility of three groups of hosts: those naturally infected with whipworms, those naturally uninfected with whipworms, and those origi~ nally naturally infected but later deinfected by treatment with the anthelminthic Ivermectin. Prevalence of T. dipodomys was higher in D. rnicrops (.53%) than in D. ordU (14%). Apparent dry matter digestibility was reduced by whipworm infection in D. -

Fleas, Hosts and Habitat: What Can We Predict About the Spread of Vector-Borne Zoonotic Diseases?

2010 Fleas, Hosts and Habitat: What can we predict about the spread of vector-borne zoonotic diseases? Ph.D. Dissertation Megan M. Friggens School of Forestry I I I \, l " FLEAS, HOSTS AND HABITAT: WHAT CAN WE PREDICT ABOUT THE SPREAD OF VECTOR-BORNE ZOONOTIC DISEASES? by Megan M. Friggens A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Forest Science Northern Arizona University May 2010 ?Jii@~-~-u-_- Robert R. Parmenter, Ph. D. ~",l(*~ l.~ Paulette L. Ford, Ph. D. --=z:r-J'l1jU~ David M. Wagner, Ph. D. ABSTRACT FLEAS, HOSTS AND HABITAT: WHAT CAN WE PREDICT ABOUT THE SPREAD OF VECTOR-BORNE ZOONOTIC DISEASES? MEGAN M. FRIGGENS Vector-borne diseases of humans and wildlife are experiencing resurgence across the globe. I examine the dynamics of flea borne diseases through a comparative analysis of flea literature and analyses of field data collected from three sites in New Mexico: The Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge, the Sandia Mountains and the Valles Caldera National Preserve (VCNP). My objectives were to use these analyses to better predict and manage for the spread of diseases such as plague (Yersinia pestis). To assess the impact of anthropogenic disturbance on flea communities, I compiled and analyzed data from 63 published empirical studies. Anthropogenic disturbance is associated with conditions conducive to increased transmission of flea-borne diseases. Most measures of flea infestation increased with increasing disturbance or peaked at intermediate levels of disturbance. Future trends of habitat and climate change will probably favor the spread of flea-borne disease. -

Comparative Ability of Oropsylla Montana and Xenopsylla Cheopis Fleas to Transmit Yersinia Pestis by Two Different Mechanisms

RESEARCH ARTICLE Comparative Ability of Oropsylla montana and Xenopsylla cheopis Fleas to Transmit Yersinia pestis by Two Different Mechanisms B. Joseph Hinnebusch*, David M. Bland, Christopher F. Bosio, Clayton O. Jarrett Laboratory of Zoonotic Pathogens, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Hamilton, Montana, United States of America * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract a1111111111 a1111111111 Background Transmission of Yersinia pestis by flea bite can occur by two mechanisms. After taking a blood meal from a bacteremic mammal, fleas have the potential to transmit the very next OPEN ACCESS time they feed. This early-phase transmission resembles mechanical transmission in some Citation: Hinnebusch BJ, Bland DM, Bosio CF, respects, but the mechanism is unknown. Thereafter, transmission occurs after Yersinia Jarrett CO (2017) Comparative Ability of Oropsylla pestis forms a biofilm in the proventricular valve in the flea foregut. The biofilm can impede montana and Xenopsylla cheopis Fleas to Transmit and sometimes completely block the ingestion of blood, resulting in regurgitative transmis- Yersinia pestis by Two Different Mechanisms. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11(1): e0005276. doi:10.1371/ sion of bacteria into the bite site. In this study, we compared the relative efficiency of the two journal.pntd.0005276 modes of transmission for Xenopsylla cheopis, a flea known to become completely blocked Editor: Christian Johnson, Fondation Raoul at a high rate, and Oropsylla montana, a flea that has been considered to rarely develop pro- Follereau, FRANCE ventricular blockage. Received: June 22, 2016 Methodology/Principal findings Accepted: December 21, 2016 Fleas that took an infectious blood meal containing Y. -

Ground Squirrels Live in Burrows That Are Litter Size: Five to Seven

L-1909 6/13 Controlling GROUND SQUIRRELDamage round squirrels are small, burrowing rodents earthen dikes with their burrows. Their burrow- found throughout the state, with the excep- ing and gnawing behavior also can cause damage G tion of extreme East Texas. There are five in irrigated areas. different species in Texas. These are the thirteen- lined ground squirrel, Mexican ground squirrel, spotted ground squirrel, rock squirrel, and the Texas antelope ground squirrel. Most ground Biology and Reproduction squirrels prefer grassy areas such as pastures, Rock squirrels golf courses, cemeteries and parks. Rock squir- Adult weight: 1½ to 1¾ pounds. rels are nearly always found in rocky cliffs, Total length: 18 to 21 inches. boulders, and canyon walls. The rock squirrel Color: Varies from dark gray to black. and thirteen-lined ground squirrel are the two species that most commonly cause damage by Tail: 7 to 10 inches, somewhat bushy. their burrowing and gnawing. Gestation period: Approximately 30 days. Ground squirrels live in burrows that are Litter size: Five to seven. usually 2 to 3 inches in diameter and 15 to 20 Number of litters: Possibly two per year, feet long. The burrow system usually has two usually born from April to August. entrances. Dirt piles around the entry holes are seldom evident. Rock squirrels and thirteen- Life span: 4 to 5 years. lined ground squirrels may hibernate during the Thirteen-lined ground squirrels coldest periods of winter. Adult weight: 5 to 9 ounces. Damage Total length: 7 to 12 inches. Ground squirrels normally do not cause Color: Light to dark brown with 13 stripes extensive damage in urban areas. -

Texosporium Sancti-Jacobi, a Rare Western North American Lichen

4347 The Bryologist 95(3), 1992, pp. 329-333 Copyright © 1992 by the American Bryological and Lichenological Society, Inc. Texosporium sancti-jacobi, a Rare Western North American Lichen BRUCE MCCUNE Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331-2902 ROGER ROSENTRETER Bureau of Land Management, Idaho State Office, 3380 Americana Terrace, Boise, ID 83706 Abstract. The lichen Texosporium sancti-jacobi (Ascomycetes: Caliciales) is known from only four general locations worldwide, all in western U.S.A. Typical habitat of Texosporium has the following characteristics: arid or semiarid climate; nearly flat ground; noncalcareous, nonsaline, fine- or coarse-textured soils developed on noncalcareous parent materials; little evidence of recent disturbance; sparse vascular plant vegetation; and dominance by native plant species. Within these constraints Texosporium occurs on restricted microsites: partly decomposed small mammal dung or organic matter infused with soil. The major threat to long-term survival of Texosporium is loss of habitat by extensive destruction of the soil crust by overgrazing, invasion of weedy annual grasses and resulting increases in fire frequency, and conversion of rangelands to agriculture and suburban developments. Habitat protection efforts are important to perpetuate this species. The lichen Texosporium sancti-jacobi (Tuck.) revisited. The early collections from that area have vague Nadv. is globally ranked (conservation status G2) location data while more recent collections (1950s-1960s) by the United States Rare Lichen Project (S. K. were from areas that are now heavily developed and pre- sumably do not support the species. New sites were sought Pittam 1990, pers. comm.). A rating of G2 means in likely areas, especially in southwest Idaho, northern that globally the species is very rare, and that the Nevada, and eastern Oregon. -

Chisel-Toothed Kangaroo Rat (Dipodomys Microps Alfredi)

Version 2020-04-20 [A race of the] Chisel-toothed Kangaroo Rat (Dipodomys microps alfredi) Species Status Statement. Distribution This subspecies is endemic to Utah and occurs only on Gunnison Island in the Great Salt Lake. Durrant (1952, p. 274) considered this kangaroo rat to be the most distinctive of the mammal subspecies that are endemic to islands in the Great Salt Lake—so distinctive that he even considered the possibility that it may deserve full species status. Table 1. Utah counties currently occupied by this species. [a Race of the] Chisel-toothed Kangaroo Rat - alfredi BOX ELDER Abundance and Trends Oliver (field notes, 15 July 2014 and 22 October 2014) captured numerous individuals on the north and south sides of Gunnison Island. However, its population trends are unknown. Statement of Habitat Needs and Threats to the Species. Habitat Needs The chisel-toothed kangaroo rat (Dipodomys microps, full species) is a dietary and a habitat specialist, and typically lives in association with either saltbush (Atriplex sp.) or blackbrush (Coleogyne sp.). However in some places it is found in association with greasewood (Sarcobatus sp.), sagebrush (Artemisia sp.), and a few other desert shrubs. Native perennial grasses are thought to be well-tolerated by the species, but introduced annual grasses are considered to impact it negatively (see review of ecology in Hayssen 1991). Threats to the Species The State of Utah owns Gunnison Island, and the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources administers it as a bird nesting colony. Therefore many potential anthropogenic threats are already prevented. The principal threat to the existence of Dipodomys microps alfredi is the dewatering of the Great Salt Lake. -

Small Mammals of the National Reactor Testing Station, Idaho Dorald M

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 33 | Number 4 Article 6 12-31-1973 Small mammals of the National Reactor Testing Station, Idaho Dorald M. Allred Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Allred, Dorald M. (1973) "Small mammals of the National Reactor Testing Station, Idaho," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 33 : No. 4 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol33/iss4/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. SMALL MAMMALS OF THE NATIONAL REACTOR TESTING STATION, IDAHO^ Dorald M. Allred= Abstract.— During studies of ectoparasites in 12 plant communities in 1966 and 1967, five types of traps were used to capture 2,478 mammals of the follow- ing 1 1 species: Dipodomys ordii, Euiamias minimus, Microtus montanus, Onychomys leucogaster, Perognathus parvus, Peromyscus maniculatus, Reithro- dontomys megalotis, Sorex merriami, Spermophilus townsendii, Neotoma cinerea, and Thomomys talpoides. The most abundant species was D. ordii and the least, M. montanus. Plant communities which contained the greatest number of species were the Chrysothamnus-Artemisia and Chrysothamnus-grass Tetradymia. Fewest species were found in the grass and Juniperus communities. Greatest populations were in the Juniperus and grass communities, and lowest populations in the Artemisia-Chrysothamnus, Artemisia- Atriplex, and Chrysothamnus-grass-Tetrady- mia associations. Between June 1966 and September 1967, ectoparasites were col- lected from mammals at the National Reactor Testing Station by personnel of Brigham Young University. -

Distribution and Abundance of Hoary Marmots in North Cascades National Park Complex, Washington, 2007-2008

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Distribution and Abundance of Hoary Marmots in North Cascades National Park Complex, Washington, 2007-2008 Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NOCA/NRTR—2012/593 ON THE COVER Hoary Marmot (Marmota caligata) Photograph courtesy of Roger Christophersen, North Cascades National Park Complex Distribution and Abundance of Hoary Marmots in North Cascades National Park Complex, Washington, 2007-2008 Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NOCA/NRTR—2012/593 Roger G. Christophersen National Park Service North Cascades National Park Complex 810 State Route 20 Sedro-Woolley, WA 98284 June 2012 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series provides contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

(Amaranthaceae) in Italy. V. Atriplex Tornabenei

Phytotaxa 145 (1): 54–60 (2013) ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ Article PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.145.1.6 Studies on the genus Atriplex (Amaranthaceae) in Italy. V. Atriplex tornabenei DUILIO IAMONICO1 1 Laboratory of Phytogeography and Applied Geobotany, Department PDTA, Section Environment and Landscape, University of Rome Sapienza, 00196 Roma, Italy. Email: [email protected] Abstract The typification of the name Atriplex tornabenei (a nomen novum pro A. arenaria) is discussed. An illustration by Cupani is designated as the lectotype, while a specimen from FI is designated as the epitype. Chorological and morphological notes in comparison with the related species A. rosea and A. tatarica are also provided. A nomenclatural change (Atriplex tornabenei subsp. pedunculata stat. nov.) is proposed. Key words: Atriplex tornabenei var. pedunculata, epitype, infraspecific variability, lectotype, Mediterranean, nomenclatural change, nomen novum Introduction Atriplex Linnaeus (1753: 1054) is a genus of about 260 species distributed in arid and semiarid regions of Eurasia, America and Australia (Sukhorukov & Danin 2009). Several names (at species, subspecies, variety and form ranks) were described related to the high phenotipic variability of this critical genus (Al-Turki et al. 2000). As conseguence, misapplication of names and nomenclatural disorders exist and need clarification. In this paper, the identity of the A. tornabenei Tineo ex Gussone (1843: 589) is discussed as part of the treatment of the genus Atriplex for the new edition of the Italian Flora (editor, Prof. S. Pignatti) and within the initiative “Italian Loci Classici Census” (Domina et al. -

Sound Communication in the Uinta Ground Squirrel

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-1965 Sound Communication in the Uinta Ground Squirrel Donna Mae Balph Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Environmental Public Health Commons Recommended Citation Balph, Donna Mae, "Sound Communication in the Uinta Ground Squirrel" (1965). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 1552. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/1552 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOUND COMMUNICATION IN THE UINTA GROUND SQUIRREL by Donna Mae Balph A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Wildlife Biology Approved: Major Professor ~ &1 Gradua'te Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 1965 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION GENERAL LIFE HISTORY 2 METHODS AND APPARATUS 7 RESULTS 1 0 Use of calls in interaction with conspeci fics 10 Chirp 10 Chirp by males 10 Chirp by females 1 7 Churr 22 Squeal 24 Squawk 24 Teeth clatter 31 Growl 34 Use of calls by juveniles 34 Comparison of chirp and churr 36 Use of calls in interaction with other species . 43 Reaction to airborne predators 43 Reaction to predators on ground 47 Reaction to snakes 52 DISCUSSION . 55 Unspecifi c ilEilur~-.jJl call s 55 Ease of location of calls 57 CONCLUSIONS 59 LITERATURE CITED 61 LIST OF TABLES Table Page 1.