Factors Associated with Home Births Among Rural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gomba District Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profi Le

Gomba District Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profi le 2016 GOMBA DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE a Acknowledgment On behalf of Office of the Prime Minister, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to all of the key stakeholders who provided their valuable inputs and support to this Multi-Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability mapping exercise that led to the production of comprehensive district Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability (HRV) profiles. I extend my sincere thanks to the Department of Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Management, under the leadership of the Commissioner, Mr. Martin Owor, for the oversight and management of the entire exercise. The HRV assessment team was led by Ms. Ahimbisibwe Catherine, Senior Disaster Preparedness Officer supported by Mr. Ogwang Jimmy, Disaster Preparedness Officer and the team of consultants (GIS/DRR specialists); Dr. Bernard Barasa, and Mr. Nsiimire Peter, who provided technical support. Our gratitude goes to UNDP for providing funds to support the Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Mapping. The team comprised of Mr. Steven Goldfinch – Disaster Risk Management Advisor, Mr. Gilbert Anguyo - Disaster Risk Reduction Analyst, and Mr. Ongom Alfred-Early Warning system Programmer. My appreciation also goes to Gomba District Team. The entire body of stakeholders who in one way or another yielded valuable ideas and time to support the completion of this exercise. Hon. Hilary O. Onek Minister for Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Refugees GOMBA DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The multi-hazard vulnerability profile outputs from this assessment for Gomba District was a combination of spatial modeling using adaptive, sensitivity and exposure spatial layers and information captured from District Key Informant interviews and sub-county FGDs using a participatory approach. -

STATEMENT by H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of the Republic

STATEMENT by H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of the Republic of Uganda At The Annual Budget Conference - Financial Year 2016/17 For Ministers, Ministers of State, Head of Public Agencies and Representatives of Local Governments November11, 2015 - UICC Serena 1 H.E. Vice President Edward Ssekandi, Prime Minister, Rt. Hon. Ruhakana Rugunda, I was informed that there is a Budgeting Conference going on in Kampala. My campaign schedule does not permit me to attend that conference. I will, instead, put my views on paper regarding the next cycle of budgeting. As you know, I always emphasize prioritization in budgeting. Since 2006, when the Statistics House Conference by the Cabinet and the NRM Caucus agreed on prioritization, you have seen the impact. Using the Uganda Government money, since 2006, we have either partially or wholly funded the reconstruction, rehabilitation of the following roads: Matugga-Semuto-Kapeeka (41kms); Gayaza-Zirobwe (30km); Kabale-Kisoro-Bunagana/Kyanika (101 km); Fort Portal- Bundibugyo-Lamia (103km); Busega-Mityana (57km); Kampala –Kalerwe (1.5km); Kalerwe-Gayaza (13km); Bugiri- Malaba/Busia (82km); Kampala-Masaka-Mbarara (416km); Mbarara-Ntungamo-Katuna (124km); Gulu-Atiak (74km); Hoima-Kaiso-Tonya (92km); Jinja-Mukono (52km); Jinja- Kamuli (58km); Kawempe-Kafu (166km); Mbarara-Kikagati- Murongo Bridge (74km); Nyakahita-Kazo-Ibanda-Kamwenge (143km); Tororo-Mbale-Soroti (152km); Vurra-Arua-Koboko- Oraba (92km). 2 We are also, either planning or are in the process of constructing, re-constructing or rehabilitating -

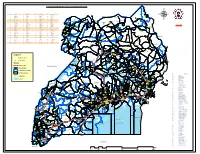

UGANDA: PLANNING MAP (Details)

IMU, UNOCHA Uganda http://www.ugandaclusters.ug http://ochaonline.un.org UGANDA: PLANNING MAP (Details) SUDAN NARENGEPAK KARENGA KATHILE KIDEPO NP !( NGACINO !( LOPULINGI KATHILE AGORO AGU FR PABAR AGORO !( !( KAMION !( Apoka TULIA PAMUJO !( KAWALAKOL RANGELAND ! KEI FR DIBOLYEC !( KERWA !( RUDI LOKWAKARAMOE !( POTIKA !( !( PAWACH METU LELAPWOT LAWIYE West PAWOR KALAPATA MIDIGO NYAPEA FR LOKORI KAABONG Moyo KAPALATA LODIKO ELENDEREA PAJAKIRI (! KAPEDO Dodoth !( PAMERI LAMWO FR LOTIM MOYO TC LICWAR KAPEDO (! WANDI EBWEA VUURA !( CHAKULYA KEI ! !( !( !( !( PARACELE !( KAMACHARIKOL INGILE Moyo AYUU POBURA NARIAMAOI !( !( LOKUNG Madi RANGELAND LEFORI ALALI OKUTI LOYORO AYIPE ORAA PAWAJA Opei MADI NAPORE MORUKORI GWERE MOYO PAMOYI PARAPONO ! MOROTO Nimule OPEI PALAJA !( ALURU ! !( LOKERUI PAMODO MIGO PAKALABULE KULUBA YUMBE PANGIRA LOKOLIA !( !( PANYANGA ELEGU PADWAT PALUGA !( !( KARENGA !( KOCHI LAMA KAL LOKIAL KAABONG TEUSO Laropi !( !( LIMIDIA POBEL LOPEDO DUFILE !( !( PALOGA LOMERIS/KABONG KOBOKO MASALOA LAROPI ! OLEBE MOCHA KATUM LOSONGOLO AWOBA !( !( !( DUFILE !( ORABA LIRI PALABEK KITENY SANGAR MONODU LUDARA OMBACHI LAROPI ELEGU OKOL !( (! !( !( !( KAL AKURUMOU KOMURIA MOYO LAROPI OMI Lamwo !( KULUBA Koboko PODO LIRI KAL PALORINYA DUFILE (! PADIBE Kaabong LOBONGIA !( LUDARA !( !( PANYANGA !( !( NYOKE ABAKADYAK BUNGU !( OROM KAABONG! TC !( GIMERE LAROPI PADWAT EAST !( KERILA BIAFRA !( LONGIRA PENA MINIKI Aringa!( ROMOGI PALORINYA JIHWA !( LAMWO KULUYE KATATWO !( PIRE BAMURE ORINJI (! BARINGA PALABEK WANGTIT OKOL KINGABA !( LEGU MINIKI -

FY 2020/21 Vote : 591 Gomba District

LG Budget Framework Paper Vote : 591 Gomba District FY 2020/21 Foreword The Local Government Budget Frame Work Paper is a document that provides a detailed analysis on all local government revenues and allocations for FY 2020/20221.This document has been prepared according to the provisions of the Budget ACT 2001, The First Budget Call Circular for FY 2020/2021 and Guide lines received from the Ministry of Finance Planning and Economic Development. The document gives a summary of revenue performance over the first quarter of FY 2019/2020 and projections and Allocations for the next FY 2020/2021.It also gives constraints which restrain departmental performance and these basically include; Inadequate Locally raised revenue, Decreasing central government transfers etc. This paper has been formulated through consultations from all key stake holders and has taken into account national priorities i.e Primary Health Care , Primary Education , Rural Water and sanitation ,Feeder roads and Agricultural Extension. The document outlines the Medium term objectives, Priorities , Outputs and Expenditure allocations. The departmental policies, emerging policy issues, sector outputs, Activities and service delivery indicators. Departmental key performance. It also involves the daft annual Work plans for all departments and activity implementation plans for the FY 2020/2021 for all the departments. In a special way, I wish to extend my gratitude to the District executive and the technical staff for the effort and support rendered towards compilation of -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

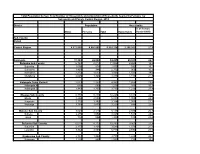

Population by Parish

Total Population by Sex, Total Number of Households and proportion of Households headed by Females by Subcounty and Parish, Central Region, 2014 District Population Households % of Female Males Females Total Households Headed HHS Sub-County Parish Central Region 4,672,658 4,856,580 9,529,238 2,298,942 27.5 Kalangala 31,349 22,944 54,293 20,041 22.7 Bujumba Sub County 6,743 4,813 11,556 4,453 19.3 Bujumba 1,096 874 1,970 592 19.1 Bunyama 1,428 944 2,372 962 16.2 Bwendero 2,214 1,627 3,841 1,586 19.0 Mulabana 2,005 1,368 3,373 1,313 21.9 Kalangala Town Council 2,623 2,357 4,980 1,604 29.4 Kalangala A 680 590 1,270 385 35.8 Kalangala B 1,943 1,767 3,710 1,219 27.4 Mugoye Sub County 6,777 5,447 12,224 3,811 23.9 Bbeta 3,246 2,585 5,831 1,909 24.9 Kagulube 1,772 1,392 3,164 1,003 23.3 Kayunga 1,759 1,470 3,229 899 22.6 Bubeke Sub County 3,023 2,110 5,133 2,036 26.7 Bubeke 2,275 1,554 3,829 1,518 28.0 Jaana 748 556 1,304 518 23.0 Bufumira Sub County 6,019 4,273 10,292 3,967 22.8 Bufumira 2,177 1,404 3,581 1,373 21.4 Lulamba 3,842 2,869 6,711 2,594 23.5 Kyamuswa Sub County 2,733 1,998 4,731 1,820 20.3 Buwanga 1,226 865 2,091 770 19.5 Buzingo 1,507 1,133 2,640 1,050 20.9 Maziga Sub County 3,431 1,946 5,377 2,350 20.8 Buggala 2,190 1,228 3,418 1,484 21.4 Butulume 1,241 718 1,959 866 19.9 Kampala District 712,762 794,318 1,507,080 414,406 30.3 Central Division 37,435 37,733 75,168 23,142 32.7 Bukesa 4,326 4,711 9,037 2,809 37.0 Civic Centre 224 151 375 161 14.9 Industrial Area 383 262 645 259 13.9 Kagugube 2,983 3,246 6,229 2,608 42.7 Kamwokya -

Legend " Wanseko " 159 !

CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA_ELECTORAL AREAS 2016 CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA GAZETTED ELECTORAL AREAS FOR 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY 266 LAMWO CTY 51 TOROMA CTY 101 BULAMOGI CTY 154 ERUTR CTY NORTH 165 KOBOKO MC 52 KABERAMAIDO CTY 102 KIGULU CTY SOUTH 155 DOKOLO SOUTH CTY Pirre 1 BUSIRO CTY EST 53 SERERE CTY 103 KIGULU CTY NORTH 156 DOKOLO NORTH CTY !. Agoro 2 BUSIRO CTY NORTH 54 KASILO CTY 104 IGANGA MC 157 MOROTO CTY !. 58 3 BUSIRO CTY SOUTH 55 KACHUMBALU CTY 105 BUGWERI CTY 158 AJURI CTY SOUTH SUDAN Morungole 4 KYADDONDO CTY EST 56 BUKEDEA CTY 106 BUNYA CTY EST 159 KOLE SOUTH CTY Metuli Lotuturu !. !. Kimion 5 KYADDONDO CTY NORTH 57 DODOTH WEST CTY 107 BUNYA CTY SOUTH 160 KOLE NORTH CTY !. "57 !. 6 KIIRA MC 58 DODOTH EST CTY 108 BUNYA CTY WEST 161 OYAM CTY SOUTH Apok !. 7 EBB MC 59 TEPETH CTY 109 BUNGOKHO CTY SOUTH 162 OYAM CTY NORTH 8 MUKONO CTY SOUTH 60 MOROTO MC 110 BUNGOKHO CTY NORTH 163 KOBOKO MC 173 " 9 MUKONO CTY NORTH 61 MATHENUKO CTY 111 MBALE MC 164 VURA CTY 180 Madi Opei Loitanit Midigo Kaabong 10 NAKIFUMA CTY 62 PIAN CTY 112 KABALE MC 165 UPPER MADI CTY NIMULE Lokung Paloga !. !. µ !. "!. 11 BUIKWE CTY WEST 63 CHEKWIL CTY 113 MITYANA CTY SOUTH 166 TEREGO EST CTY Dufile "!. !. LAMWO !. KAABONG 177 YUMBE Nimule " Akilok 12 BUIKWE CTY SOUTH 64 BAMBA CTY 114 MITYANA CTY NORTH 168 ARUA MC Rumogi MOYO !. !. Oraba Ludara !. " Karenga 13 BUIKWE CTY NORTH 65 BUGHENDERA CTY 115 BUSUJJU 169 LOWER MADI CTY !. -

PBU AGENTS Central Region

PBU AGENTS Central Region Name of Agent or Outlet Place of Business District Abusha Junior (U) Ltd Bombo Luweero Parmer Financial Services Ltd Kapeeka Nakaseke Q&A Education and Management Consultancy Bombo Luweero Holy Saints Uganda Limited Bombo T/C Luweero Danortry Financial Link (U) Ltd Opposite PostBank Bombo Branch Luwero Dithcom Trading Co. Limited Opposite Centenary Bank ATM Luwero Glarison Technologies Limited Near the Barracks Luwero Nasu Express Outlet Bombo, near SR Fuel Station Luwero Nasu Express Outlet Opposite Bombo UPDF Play ground Luwero Uganda Post Limited Kyambogo Kampala Uganda Post Limited Nakawa Kampala NIK Tel Traders Nakawa Kampala Prime Secretarial Services Luzira Stage 6 Kampala ESSIE. RE Classic Fashions Biina Mutungo Kampala Nandudu Babra Kireka Wakiso Blessed Mina General Merchandise Kireka Wakiso Niktel Traders Pioneer Mall Kampala 6 GS Money Point Kireka Kampala Cinemax General Hardware Bweyogerere Wakiso Ariong Enterprises Mutungo Kampala Isip Connections Ltd Bugolobi Kampala Kireka BodaBoda Police Stage Co-Operative Kireka Kampala Savings and Credit Society Limited Chelanasta Cash Point Solutions Jinja Highway, Mukono Mukono Milly's Laundry Opposite UCU Main Gate Mukono Rana Phones 83 Enterprises Opp Kirinya Shopping Centre Wakiso Boadaph Financial Services Limited Sports Pro Hostel. Kampala Jeba (U) Limited Cwa 2 Street Kampala Tusaboomu Enterprises Ltd URA building, Nakawa Kampala Alpha Immanuel's Cash Point Najeera Road, Bweyogerere Wakiso Beulah Business Center Biina Road, Kunya Stage Kampala Kyobe -

BMAU BRIEFING PAPER (12/17) May 2017

BMAU BRIEFING PAPER (12/17) May 2017 WHAT ARE THE KEY ISSUES IN THE HEALTH SECTOR? Overview Key Issues The health sector aims at producing a healthy and productive population that effectively contributes to socio- Remuneration packages for health staff are economic growth. This is achievable through provision of inadequate . accessible and quality health care to all people in Uganda through delivery of promotive, preventive, curative, Inadequate staffing has in part resulted in palliative and rehabilitative care (Second National non-utilisation of some key service delivery Development Plan [NDP II] 2015/16-2019/20 p.188) equipment. Human capital development is a key priority in NDPII. The The health facilities are experiencing drug sector was allocated Ug shs 1,827.26billion in FY2016/17 stock out in part due poor planning and representing a 44% increase in the allocation from the Ug budgeting resulting into a mismatch of supply shs 1,270.81billion allocated in FY2015/16. and demand. The health sector has exhibited a good allocative efficiency through the investments in infrastructure and Health facilities either lack, or received poor other services but a number of aspects in the sector that quality or incomplete packages of equipment. affect service delivery remain less attended. The briefing paper highlights the three important aspects that require attention to enhance service delivery. the 112 districts in Uganda had either a hospital or HCIV or both regardless of the infrastructure condition. Despite this progress in service availability, significant challenges remain to Introduction improve the quality of service delivery and address Good health is instrumental in facilitating socio- continuing health status issues such as infant and economic transformation. -

Strengthening OVCMIS Repor and Utilisation in Ngthening OVCMIS

Strengthening OVCMIS reporting and Utilisation in Gomba district Presented by Kashemeire e Obadiah & Magall Moritz MAKSPH‐CDC Medium m Term M&E Fellows 2011/12 Presentation Outline line • Background • Problem Statement • Project Objectives • Project Implementation • Project deliverables • Challenges • Lessons learnt • Recommendations • Acknowledgements Background • The Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development (MGLSD) is a lead government agency mandated to ensure that the rights of all children including Orphans and other Vulnerable (OVC) are promoted and upheld . • The Ministry works through district local governments to deliver decentralized child care and protection services for children. OVC‐ ‐MIS The OVC‐ Management Information System was established by the Ministry to monitor OVC implementation and evaluate performance of all stakeholders to ensure effective implementation of National OVC response esponse. The OVCMIS is based on the conceptual framework that links; • The needs of OVC and their households • The provision of services by government, donors and CSOs. • The demand and utilization of services by the OVC and their households ds. OVCMIS data flow flow • OVCMIS data flow Problem Statement 32 “new” Districts including Gomba do not receive any support to roll out OVCMIS from SUNRISE project which operates in 80 “old” districts. In Gomba, staff lacked the basic skills for OVCMIS data collection, analysis and online reporting. The focal office does not have a printer for printing data collection tools. There was no internet connectivity for online reporting. Parishes are very large with many villages. CDOs have no motorcycles. Project Implementation Area In view of the problems and the time and budget allocated to this project, Gomba district which is within easy reach of project implementers was selected to act as a pilot district where success stories, good practices and challenges will be documented and shared to inform implementation in the rest of the districts and municipalities. -

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS SUPPLEMENT No. 5 3Rd February

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS SUPPLEMENT No. 5 3rd February, 2012 STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS SUPPLEMENT to The Uganda Gazette No. 7 Volume CV dated 3rd February, 2012 Printed by UPPC, Entebbe, by Order of the Government. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2012 No. 5. The Local Government (Declaration of Towns) Regulations, 2012. (Under sections 7(3) and 175(1) of the Local Governments Act, Cap. 243) In exercise of the powers conferred upon the Minister responsible for local governments by sections 7(3) and 175(1) of the Local Governments Act, in consultation with the districts and with the approval of Cabinet, these Regulations are made this 14th day of July, 2011. 1. Title These Regulations may be cited as the Local Governments (Declaration of Towns) Regulations, 2012. 2. Declaration of Towns The following areas are declared to be towns— (a) Amudat - consisting of Amudat trading centre in Amudat District; (b) Buikwe - consisting of Buikwe Parish in Buikwe District; (c) Buyende - consisting of Buyende Parish in Buyende District; (d) Kyegegwa - consisting of Kyegegwa Town Board in Kyegegwa District; (e) Lamwo - consisting of Lamwo Town Board in Lamwo District; - consisting of Otuke Town Board in (f) Otuke Otuke District; (g) Zombo - consisting of Zombo Town Board in Zombo District; 259 (h) Alebtong (i) Bulambuli (j) Buvuma (k) Kanoni (l) Butemba (m) Kiryandongo (n) Agago (o) Kibuuku (p) Luuka (q) Namayingo (r) Serere (s) Maracha (t) Bukomansimbi (u) Kalungu (v) Gombe (w) Lwengo (x) Kibingo (y) Nsiika (z) Ngora consisting of Alebtong Town board in Alebtong District; -

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS)

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7, as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties. Note for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Bureau. Compilers are strongly urged to provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of maps. Nabajjuzi Wetland System Ramsar Information Sheet 1. Name and address of the RIS compiler: Achilles Byaruhanga and Stephen Kigoolo NatureUganda Plot 83 Tufnel Drive, Kamwokya, P. O Box 27034, Kampala, Uganda. Tel: 256 41 540719 Fax no: 256 41 533 528 E-mail: [email protected] 2. Date: 20 September 2005. 3. Country: The Republic of Uganda 4. Name of the Ramsar site: Nabajjuzi Wetland System 5. Map of the Ramsar Site: Hard copy: attached Digital (electronic) format: yes 6. Geographical coordinates: 31o33’ – 31o49” E and 00o27” S – 00o05” N. 7. General Location: Nabajjuzi wetland system lies south west of central Uganda in Masaka district (Lwabenge, Kyamulibwa, Kalungu, Mukungwe, Nyendo, Kimanya, Katwe, Kingo, Kibinge, Butenga and Bigasa sub-counties), Sembabule district (Mijwala sub-county) and Mpigi district (Kabulasoke sub-county). It stretches up to the Kagera River basin area to the north and past the periphery of Masaka Town Municipal Council along Masaka – Mbarara highway to the south. 8.