Post-Colonial Challenges, Connections and Contributions *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NAMASTE MALAYSIA Volume 1/2017

NAMASTE MALAYSIA Volume 1/2017 HIGH COMMISSION OF MALAYSIA IN NEW DELH, INDIA NAMASTE MALAYSIA Volume 1/2017 January - June 2017 OFFICIAL VISIT OF YAB In this Issue: PRIME MINISTER TO Official Visit of YAB INDIA Prime Minister Malaysia-India Bilateral Meeting YAB Prime Minister Stop-over in Chennai YAB Prime Minister Visits Historic City of Jaipur Official Opening Ceremo- ny of the New High Commission of Malaysia Complex in New Delhi YAB Prime Minister with the Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi before the Bilateral Meeting at Hyderabad House, New Delhi New High Commissioner of Malaysia to India The Prime Minister of Malaysia, YAB also visited Chennai and Jaipur. Dato’ Sri Mohd Najib Tun Abdul Both Malaysia and India signed Global Rajasthan Razak undertook an Official Visit to s e v e n A g r e e m e n t s a n d Agritech Meet (GRAM) India from 30 March – 4 April 2017. Memoranda of Understanding 2017 The visit was at the invitation of the (MoU), as well as 31 business MoUs Indian Prime Minister, Narendra worth RM 158.4 billion (USD 36 High Commissioner Modi. YAB Prime Minister was billion). Working Visit to accompanied by YABhg. Datin Sri Mumbai Rosmah Mansor, as well as 11 The visit could not come at a Cabinet Ministers, including YB better time, as this year, not only Iftar and Terawih Dato’ Seri Mustapa Mohamed Malaysia celebrates its 60th Prayers with Malaysians (Minister of International Trade and National Day, but also its 60th Residing in New Delhi Industry), YB Dato’ Sri Liow Tiong anniversary of diplomatic relations Lai (Minister of Transport) and YB with India. -

Pdf MATRADE (2005)

Asian Social Science May, 2008 An Assessment of Analysis on the Penetration of Malaysian Contractors into India Nur Aishah Mohd Hamdan, Hamimah Adnan Department of Quantity Surveying Faculty of Architecture, Planning and Surveying Universiti Teknologi MARA,Shah Alam, Selangor MALAYSIA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper will give insight to India as a developing country and an emerging super-power in the world’s economy. It will explain the factors that contribute to the development of India and the changes India has gone through to achieve the success. Following a thorough literature review, questionnaire surveys were sent out to G7 contractors registered under CIDB Malaysia to understand the situation of contractors in their venture into the Indian construction market. It was found that the successful contractors viewed profit margin as the most important factor when tendering compared to building reputation in the Indian market. The contractors need to make groundwork or research, build/increase tolerance and skills in negotiation. An offer of attractive financial package and comprehensive services and good Indian partnership with local representatives to build better relationship and accumulate better market information are several main factors to succeed in the Indian construction market. The findings of this research provide useful information for any contractors to their intention in penetrate the Indian construction market. Keywords: Penetration, Malaysian Contractors, India 1. Introduction The Indian construction industry growth was quite volatile especially in the early years since the liberalisation of its economy. The growth has escalated to a more comfortable momentum since 1998 due to the intensification of construction investments by the government. -

Black Europeans, the Indian Coolies and Empire: Colonialisation and Christianized Indians in Colonial Malaya & Singapore, C

Black Europeans, the Indian Coolies and Empire: Colonialisation and Christianized Indians in Colonial Malaya & Singapore, c. 1870s - c. 1950s By Marc Rerceretnam A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Sydney. February, 2002. Declaration This thesis is based on my own research. The work of others is acknowledged. Marc Rerceretnam Acknowledgements This thesis is primarily a result of the kindness and cooperation extended to the author during the course of research. I would like to convey my thanks to Mr. Ernest Lau (Methodist Church of Singapore), Rev. Fr. Aloysius Doraisamy (Church of Our Lady of Lourdes, Singapore), Fr. Devadasan Madalamuthu (Church of St. Francis Xavier, Melaka), Fr. Clement Pereira (Church of St. Francis Xavier, Penang), the Bukit Rotan Methodist Church (Kuala Selangor), the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (Singapore), National Archives of Singapore, Southeast Asia Room (National Library of Singapore), Catholic Research Centre (Kuala Lumpur), Suara Rakyat Malaysia (SUARAM), Mr. Clement Liew Wei Chang, Brother Oliver Rodgers (De Lasalle Provincialate, Petaling Jaya), Mr. P. Sakthivel (Seminari Theoloji Malaysia, Petaling Jaya), Ms. Jacintha Stephens, Assoc. Prof. J. R. Daniel, the late Fr. Louis Guittat (MEP), my supervisors Assoc. Prof. F. Ben Tipton and Dr. Lily Rahim, and the late Prof. Emeritus S. Arasaratnam. I would also like to convey a special thank you to my aunt Clarice and and her husband Alec, sister Caryn, my parents, aunts, uncles and friends (Eli , Hai Long, Maura and Tian) in Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and Penang, who kindly took me in as an unpaying lodger. -

A Chan, a Tancareira

INDEX “A Chan, a Tancareira” (Senna Albuquerque, Pedro António de Fernandes), 250 Meneses Noronha de, 73 Abriz, José, 38 Ali, Ha¯jı¯ Muha¯mmad, 73 Abu’l Hasan (sultan), 71 Allen, Charles Herbert, 179 Aceh Almeida, António José de Miranda e, Portuguese conflicts with, 51, 53, 36 57 Almeida, Manuel de, 122 sultan and sultanate of, 50 Almeida, Miguel Vale de, 72–73, 242, adaptation, 4–5, 6, 10, 19, 240, 255 259 Afonso, Inácio Caetano, 35, 37 An Earth-Colored Sea, 259 Africa, 12, 26, 29, 140, 173 Almeida, Teresa da Piedade de Baptista Lusophone, 131, 143, 242, 271 See Devi, Vimala (pseud.) plants from, 33, 34, 39 aloe, 40 Africans, 11, 12, 133, 135, 138, 160, althea, 40 170, 245, 249 Álvares, Gaspar Afonso, 69 See also slaves Amaral, Miguel de, 90 Agualusa, José Eduardo, 261, 265, 270 American Institute of Indian Studies, Um Estranho em Goa, 261–63, 270 xi Fronteiras Perdidas, 265 Ames, Glenn Joseph, xi–xiii “A Nossa Pátria na Malásia”, 270 works by, xiii Aguiar, António de, 86, 89, 97 Amor e Dedinhos de Pé (Senna “Ah Chan, the Tanka Girl” (Senna Fernandes), 247, 250–54 Fernandes) Amorim, Francisco Gomes de, 183 See “A Chan, a Tancareira” An Earth-Colored Sea (Almeida), 259 air forces Anderson, Benedict, 236, 240–41, 255 Royal Air Force, 217 See also imagined communities United States Army Air Forces, Anglo-Asians, 132 Fourteenth Air Force, 215 See also Luso-Asians Ajuda Palace, 36 Anglo-Indians, 134, 139 Albuquerque, Afonso de, 48, 54 and White Australia policy, 143 299 14 Portuguese_1.indd 299 10/31/11 10:17:12 AM 300 Index Anglo-Portuguese -

NAMASTE MALAYSIA a High Commission of Malaysia in New Delhi Publication

NAMASTE MALAYSIA a High Commission of Malaysia in New Delhi publication ISSUE 2019 IN THIS ISSUE VISIT BY HER MAJESTY SERI PADUKA BAGINDA Visit by Her Majesty Seri Paduka Baginda the Raja THE RAJA PERMAISURI AGONG TUNKU HAJAH Permaisuri Agong Visit by Minister of Human AZIZAH AMINAH MAIMUNAH ISKANDARIAH BINTI Resource Visit by the State Minister of ALMARHUM AL-MUTAWAAKIL ALALLAH SULTAN Selangor ISKANDAR AL-HAJ Talk on Health Tips in Preventing from Air Pollution Courtesy Call by DG of Malaysian Handicraft Development Cooperation Hari Sukan Negara 2019 62nd Malaysia National Day Reception 2nd Edition of Merdeka Golf ASEAN Fellowship for PHD 74th LO Meeting of AARDO Visit by Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department 52nd ASEAN Day Celebration Visit by Minister of Primary Resources of Malaysia Visit by DID Participants of IDFR 112th ANDC Meeting Launching Ceremony of Malindo’s Air Inaugural Flight Kuala Lumpur-Varanasi Courtesy Call by Resident Commissioner of the State of Assam AARDO Special Session And many more…. Her Majesty Seri Paduka Baginda the Raja Permaisuri Agong Tunku Hajah Azizah Aminah Maimunah Iskandariah binti Almarhum Al-Mutawaakil Alallah Sultan Iskandar Al-Haj undertook a private visit to New Delhi on 6-8 December 2019. Her Majesty attended the International Craft Award which was held in conjunction with the India Craft Week on 7 December 2019 at GMR Aerocity, New Delhi. Her Majesty received a prestigious and well-deserved award entitled Craft Icon of the Year awarded by the World Craft Council (WCC). Congratulations Her Majesty the Raja Permaisuri Agong! Page 2 NAMASTE MALAYSIA VISIT YB M. -

THE PORTUGUESE in the CREOLE INDIAN OCEAN Copyright © Fernando Rosa 2015 All Rights Reserved

Copyrighted material – 9781137563668 Contents Preface ix Acknowledgments xv 1 Introduction 1 2 Revisiting the Creole Port City 41 3 The Malabar Coast (Kerala) and Cosmopolitanism 57 4 Revisiting Creoles and Other Languages in the Lusophone Indian Ocean 89 5 (Dis)connections in Macau and Melaka: Constructing a Lusophone Indian Ocean 115 6 The Muslim and Portuguese Indian Ocean: A Reappraisal of Cosmopolitanism in the Early Modern Era 135 7 Conclusion 167 Notes 179 References 197 Index 215 Copyrighted material – 9781137563668 Copyrighted material – 9781137563668 THE PORTUGUESE IN THE CREOLE INDIAN OCEAN Copyright © Fernando Rosa 2015 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission. In accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. First published 2015 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN The author has asserted their right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of Nature America, Inc., One New York Plaza, Suite 4500, New York, NY 10004-1562. -

!! Vol. 9 No. 4 1974 .RE L3l Lll Ataysian Baha'i News Vo L:9 No.4 Dec

I\ I- ~ L:. ~ s I ~ B a~ I ~ !! Vol. 9 No. 4 1974 .RE_ l3L lll ataysian Baha'i News Vo l:9 No.4 Dec. 73-July 74 PERMANENT SEAT, UNIVERSAL HOUSE OF JUSTICE JOYFULLY ANNOUNCE ACCEPTANCE EXQUISITE DESIGN CONCEIVED BY HUSAYN AMANAT FOR BUILDING TO SERVE AS PERMANENT SEAT UNIVERSAL HOUSE OF JUSTICE MOUNT CARMEL STOP DECISION MADE TO PROCEED NEGOTIATE CONTRACTS CONSTRUCTION THIS NOBLE EDIFICE SECOND THOSE BUILDINGS DESTINED ARISE AROUND ARC CONSTITUTE ADMINISTRATIVE CENTRE BAHA'I WORLD. 7th Feb. '74. THE UNIVERSAL HOUSE OF JUSTICE Front elevation of the design for the building for the Seat of the Universal House of Justice on Mount Carmel in Haifa. The building is to be sited on the central axis of the Arc and will face northward toward 'Akka and Bahji. The architect is Mr. Husayn Amanat. Architects needed for Baha'i Temples The Universal House of Justice will soon be considering the selection of architects for the Mashriqu'l-Adhkars to be erected in India and Samoa. Those wishing to be considered as architects for either of these Temples are invited to submit statements of their qualifications. Such submission may include examples of works previously designed and/ or executed and, if desired, any thoughts or concepts of proposed designs for the Temples may be expressed in whatever way the applicant chooses. The design of each Temple will be developed by f'he architect selected in relation to the climate, environ ment and culture of the area where it is to be built. The initiation of construction of these Temples is a goal of the current Five Year Plan. -

Dr. MUBARAK RAHAMATHULLA B) Address for Communication

CURRICULUM VITAE I. PERSONAL a) Name : Dr. MUBARAK RAHAMATHULLA b) Address for communication: Department of Social Work and Social Planning, Flinders University, GPO Box 2100, Adelaide SA5100. Telephone No.: 81770329 (Residence) Telephone No.: 82012677 (Office) Mobile: +61 403494047 Email address: [email protected] II. EDUCATION 1998-2000 M.Sc. (Master of Science) in Information Technology at the Northern University of Malaysia. 1989-92 PhD. (Doctor of Philosophy) in Social Work under the Faculty of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore University, India: "Stress, coping and Social Support among the families of unmarried Muslim women with neurosis". 1986-88 M.Phil. (Master of Philosophy) in Psychiatric Social Work under the Faculty of Mental Health and Neuroscience, Bangalore Unversity, India. 1982-84 M.A. (Master of Arts) in Social Work, Bharathiar University, India. Overall grade point average: 5.69 out of 6.00. 1978-81 B.A. (Bachelor of Arts, First Class) in Public Relations, University of Madras, India 1995-96 Certificate Course in Bahasa Malaysia, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Pulau Pinang. Academic and Professional memberships and awards 2009 Flinders University Faculty of Social Sciences Teaching Award 2003-2005 Elected Executive Committee member in the South Australian branch of the Australian Association of Social Workers 2002-to date Friend of International Federation of Social Workers 1998-to date Member, Asia Pacific Association for Social Work Education (APASWE). III. PRESENT POSITION CV Dr Mubarak Rahamathulla 10/9/2010 1 Senior Lecturer (Level C), Department of Social Work and Social Planning, Flinders University, Adelaide (since 4th February, 2001). IV. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE a) Assistant Professor, Department of Social Work and Psychology, National University of Singapore, 23rd December 1991 – 31st December 2001. -

Reproduced from the Making of the Luso-Asian World

Nalanda-Sriwijaya Series General Editors: Tansen Sen and Geoff Wade The Nalanda-Sriwijaya Series, established under the publications program of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, has been created as a publications avenue for the Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre. The Centre focuses on the ways in which Asian polities and societies have interacted over time. To this end, the series invites submissions which engage with Asian historical connectivities. Such works might examine political relations between states; the trading, financial and other networks which connected regions; cultural, linguistic and intellectual interactions between societies; or religious links across and between large parts of Asia. 1. Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia, edited by Hermann Kulke, K. Kesavapany and Vijay Sakhuja 2. Early Interactions between South and Southeast Asia: Reflections on Cross-Cultural Exchange, edited by Pierre-Yves Manguin, A. Mani and Geoff Wade 3. Anthony Reid and the Study of the Southeast Asian Past, edited by Geoff Wade and Li Tana 4. Hardships and Downfall of Buddhism in India, by Giovanni Verardi The Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) was established as an autonomous organization in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are the Regional Economic Studies (RES, including ASEAN and APEC), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. -

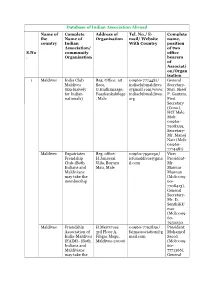

Database of Indian Association Abroad S.No . Name of the Country Complete Name of Indian Association/ Community Organisation Ad

Database of Indian Association Abroad Name of Complete Address of Tel. No./ E- Complete the Name of Organisation mail/ Website name, country Indian With Country position Association/ of two S.No community office . Organisation bearers of Associati on/Organ isation 1 Maldives India Club Reg. Office: 1st 00960-7774481/ General Maldives floor, indiaclubmaldives Secretary- (Exclusively G.Kudhimaage, @gmail.com/www. Shri. Sheel for Indian Faashankakilege indiaclubmaldives. P. Gautam, nationals) , Male org First Secretary (Cons.), HCI Male Mob: 00960- 7908339, Secretary- Mr. Manoj Nair (Mob: 00960- 7774481) Maldives Expatriates Reg. office: 00960-7950250/ Vice- Frendship H.Janavari iefcmaldives@gma President- Club-(Both Villa, Buruzu il.com Mr. Indians and Mau, Male Mannar Maldivians Mannan may take the (Mob:009 membership 60- 7708413), General Secretary- Mr. D. SenthiKU mar (Mob:009 60- 7950250 Maldives Friendship H.Merryrose 00960-7792830/ President: Association of 3rd Floor A, faimassociation@g Mohamed India-Maldives Filigas Magu, mail.com Saeed (FAIM)- (Both Maldives-20006 (Mob:009 Indians and 60- Maldivians 7771366), may take the General membership Secretary- Ms. Sofy Saeed (Mob: 0096- 7792830 2 Iceland indo Icelandic Hus- 00354-5888910/ 1. CEO, Chamber of verslunarinnar- atvinnurekendur@ Mr. Olafur Commerce kringlunni 7- atvinnurekendur.is Stephense 103 Reykjavik / N/A n, 2. Chairman, Mr. Bala Kamallakh aran Iceland Iceland-India Vatnsstigur 15, 00354-8483391/ 1. friendship appt 701 chandrika@austuri President, society 101Reykjavik ndia.is/ N/A Mrs. Chandrika Gunnarsso n, 2. Board Member, Mrs. Shyamali Ghosh Iceland Friends of Baronstigur 3, 00354-6936810/ 1. India 101 Reykjavik [email protected]/ Chairman, http://www.vinirin Mrs. dlands.is Solveig Jonasdotti r, 2.