Utah State Water Plan - West Desert Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Photograph Taken by David A

Prepared in cooperation with the National Park Service Characterization of Surface-Water Resources in the Great Basin National Park Area and Their Susceptibility to Ground-Water Withdrawals in Adjacent Valleys, White Pine County, Nevada Scientific Investigations Report 2006–5099 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Confluence of Lehman and Baker Creeks, looking west toward Great Basin National Park, White Pine County, Nevada. (Photograph taken by David A. Beck, U.S. Geological Survey, 2003.) Characterization of Surface-Water Resources in the Great Basin National Park Area and Their Susceptibility to Ground-Water Withdrawals in Adjacent Valleys, White Pine County, Nevada By Peggy E. Elliott, David A. Beck, and David E. Prudic Prepared in cooperation with the National Park Service Scientific Investigations Report 2006–5099 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Dirk Kempthorne, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey P. Patrick Leahy, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2006 For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Information Services Box 25286, Denver Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 For more information about the USGS and its products: Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/ Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Elliott, P.E., Beck, D.A., and Prudic, D.E., 2006, Characterization of surface-water resources in the Great Basin National Park area and their susceptibility to ground-water withdrawals in adjacent valleys, White Pine County, Nevada: U.S. -

Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone Land Use in Northern Nevada: a Class I Ethnographic/Ethnohistoric Overview

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Bureau of Land Management NEVADA NORTHERN PAIUTE AND WESTERN SHOSHONE LAND USE IN NORTHERN NEVADA: A CLASS I ETHNOGRAPHIC/ETHNOHISTORIC OVERVIEW Ginny Bengston CULTURAL RESOURCE SERIES NO. 12 2003 SWCA ENVIROHMENTAL CON..·S:.. .U LTt;NTS . iitew.a,e.El t:ti.r B'i!lt e.a:b ~f l-amd :Nf'arat:1.iern'.~nt N~:¥G~GI Sl$i~-'®'ffl'c~. P,rceP,GJ r.ei l l§y. SWGA.,,En:v,ir.e.m"me'Y-tfol I €on's.wlf.arats NORTHERN PAIUTE AND WESTERN SHOSHONE LAND USE IN NORTHERN NEVADA: A CLASS I ETHNOGRAPHIC/ETHNOHISTORIC OVERVIEW Submitted to BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Nevada State Office 1340 Financial Boulevard Reno, Nevada 89520-0008 Submitted by SWCA, INC. Environmental Consultants 5370 Kietzke Lane, Suite 205 Reno, Nevada 89511 (775) 826-1700 Prepared by Ginny Bengston SWCA Cultural Resources Report No. 02-551 December 16, 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................v List of Tables .................................................................v List of Appendixes ............................................................ vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................1 CHAPTER 2. ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW .....................................4 Northern Paiute ............................................................4 Habitation Patterns .......................................................8 Subsistence .............................................................9 Burial Practices ........................................................11 -

Utah Historical Quarterly, Use of the Atomic Bomb

78 102 128 NO. 2 NO. I VOL. 86 VOL. I 148 179 UHQ 75 CONTENTS Departments 78 The Crimson Cowboys: 148 Remembering Topaz and Wendover The Remarkable Odyssey of the 1931 By Christian Heimburger, Jane Beckwith, Claflin-Emerson Expedition Donald K. Tamaki, and Edwin P. Hawkins, Jr. By Jerry D. Spangler and James M. Aton 165 Voices from Drug Court By Randy Williams 102 Small but Significant: The School of Nursing at Provo 77 In This Issue General Hospital, 1904–1924 By Polly Aird 172 Book Reviews & Notices 128 The Mountain Men, the 179 In Memoriam Cartographers, and the Lakes 182 Contributors By Sheri Wysong 183 Utah In Focus Book Reviews 172 Depredation and Deceit: The Making of the Jicarilla and Ute Wars in New Mexico By Gregory F. Michno Reviewed by Jennifer Macias 173 Juan Rivera’s Colorado, 1765: The First Spaniards among the Ute and Paiute Indians on the Trail to Teguayo By Steven G. Baker, Rick Hendricks, and Gail Carroll Sargent Reviewed by Robert McPherson 175 Isabel T. Kelly’s Southern Paiute Ethnographic Field Notes, 1932–1934, Las Vegas NO. 2 NO. Edited by Catherine S. Fowler and Darla Garey-Sage I Reviewed by Heidi Roberts 176 Mountain Meadows Massacre: Collected Legal Papers Edited by Richard E. Turley, Jr., Janiece L. Johnson, VOL. 86 VOL. and LaJean Purcell Carruth I Reviewed by Gene A. Sessions. UHQ Book Notices 177 Cowboying in Canyon Country: 76 The Life and Rhymes of Fin Bayles, Cowboy Poet By Robert S. McPherson and Fin Bayles 178 Dime Novel Mormons Edited by Michael Austin and Ardis E. -

Quaternary Tectonics of Utah with Emphasis on Earthquake-Hazard Characterization

QUATERNARY TECTONICS OF UTAH WITH EMPHASIS ON EARTHQUAKE-HAZARD CHARACTERIZATION by Suzanne Hecker Utah Geologiral Survey BULLETIN 127 1993 UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY a division of UTAH DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 0 STATE OF UTAH Michael 0. Leavitt, Governor DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Ted Stewart, Executive Director UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY M. Lee Allison, Director UGSBoard Member Representing Lynnelle G. Eckels ................................................................................................... Mineral Industry Richard R. Kennedy ................................................................................................. Civil Engineering Jo Brandt .................................................................................................................. Public-at-Large C. Williatn Berge ...................................................................................................... Mineral Industry Russell C. Babcock, Jr.............................................................................................. Mineral Industry Jerry Golden ............................................................................................................. Mineral Industry Milton E. Wadsworth ............................................................................................... Economics-Business/Scientific Scott Hirschi, Director, Division of State Lands and Forestry .................................... Ex officio member UGS Editorial Staff J. Stringfellow ......................................................................................................... -

Water Resources of Millard County, Utah

WATER RESOURCES OF MILLARD COUNTY, UTAH by Fitzhugh D. Davis Utah Geological Survey, retired OPEN-FILE REPORT 447 May 2005 UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY a division of UTAH DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Although this product represents the work of professional scientists, the Utah Department of Natural Resources, Utah Geological Survey, makes no warranty, stated or implied, regarding its suitability for a particular use. The Utah Department of Natural Resources, Utah Geological Survey, shall not be liable under any circumstances for any direct, indirect, special, incidental, or consequential damages with respect to claims by users of this product. This Open-File Report makes information available to the public in a timely manner. It may not conform to policy and editorial standards of the Utah Geological Survey. Thus it may be premature for an individual or group to take action based on its contents. WATER RESOURCES OF MILLARD COUNTY, UTAH by Fitzhugh D. Davis Utah Geological Survey, retired 2005 This open-file release makes information available to the public in a timely manner. It may not conform to policy and editorial standards of the Utah Geological Survey. Thus it may be premature for an individual or group to take action based on its contents. Although this product is the work of professional scientists, the Utah Department of Natural Resources, Utah Geological Survey, makes no warranty, expressed or implied, regarding its suitability for a particular use. The Utah Department of Natural Resources, Utah Geological Survey, shall not be liable under any circumstances for any direct, indirect, special, incidental, or consequential damages with respect to claims by users of this product. -

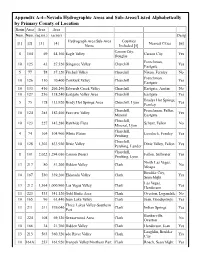

Nevada Hydrographic Areas and Sub-Areas/Listed Alphabetically by Primary County of Location Basin Area Area Area Num

Appendix A-4--Nevada Hydrographic Areas and Sub-Areas/Listed Alphabetically by Primary County of Location Basin Area Area Area Num. Num. (sq.mi.) (acres) Desig Hydrograph Area/Sub-Area Counties [1] [2] [3] [4] Nearest Cities [6] Name Included [5] Carson City, 8 104 69 44,160 Eagle Valley Carson City Yes Douglas Frenchman, 10 125 43 27,520 Stingaree Valley Churchill Yes Eastgate 5 77 58 37,120 Fireball Valley Churchill Nixon, Fernley No Frenchman, 10 126 110 70,400 Cowkick Valley Churchill Yes Eastgate 10 133 416 266,240 Edwards Creek Valley Churchill Eastgate, Austin No 10 127 216 138,240 Eastgate Valley Area Churchill Eastgate Yes Bradys Hot Springs, 5 75 178 113,920 Brady Hot Springs Area Churchill, Lyon Yes Fernley Churchill, Frenchman, Fallon, 10 124 285 182,400 Fairview Valley Yes Mineral Eastgate Churchill, 10 123 227 145,280 Rawhide Flats Schurz, Fallon No Mineral, Lyon Churchill, 4 74 164 104,960 White Plains Lovelock, Fernley Yes Pershing Churchill, 10 128 1,303 833,920 Dixie Valley Dixie Valley, Fallon Yes Pershing, Lander Churchill, 8 101 2,022 1,294,080 Carson Desert Fallon, Stillwater Yes Pershing, Lyon North Las Vegas, 13 217 80 51,200 Hidden Valley Clark No Moapa Boulder City, 10 167 530 339,200 Eldorado Valley Clark Yes Searchlight Las Vegas, 13 212 1,564 1,000,960 Las Vegas Valley Clark Yes Henderson 13 223 533 341,120 Gold Butte Area Clark Overton, Logandale No 10 165 96 61,440 Jean Lake Valley Clark Jean, Goodsprings Yes Three Lakes Valley-Southern 13 211 311 199,040 Clark Indian Springs Yes Part Bunkerville, 13 224 -

Us Department of the Interior

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY FIELD TRIP GUIDE TO THE SOUTHERN EAST HUMBOLDT RANGE AND NORTHERN CURRIE HILLS, NORTHEAST NEVADA: AGE AND STYLE OF ATTENUATION FAULTS IN PERMIAN AND TRIASSIC ROCKS by Charles H. Thorman1 and William E. Brooks1 Open-File Report 94-439 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Denver, Colorado 1994 FIELD TRIP GUIDE TO THE SOUTHERN EAST HUMBOLDT RANGE AND NORTHERN CURRIE HILLS, NORTHEAST NEVADA: AGE AND STYLE OF ATTENUATION FAULTS IN PERMIAN AND TRIASSIC ROCKS by Charles H. Thorman and William E. Brooks U.S. Geological Survey, Box 25046, MS 905, Denver, CO 80225 INTRODUCTION One of the most difficult aspects in unraveling Basin and Range geology is dating attenuation faults, which are low-angle younger-over-older faults that can be interpreted as contractional or extensional in origin. Units are typically thinned or eliminated, commonly with little discordance between juxtaposed beds. Hintze (1978) documented this style of faulting in western Utah and attributed it to the Sevier orogeny. Attenuation faults abound in the region, but are commonly difficult to date because of a lack of crosscutting or overlapping features (Nutt and others, 1992; Nutt and Thorman, 1994). Being unable to date an attenuation fault makes it difficult to relate the fault to extensional or contractional tectonics. In the case of the southern East Humboldt Range, we consider the attenuation faulting to be related to Jurassic (Elko) or Cretaceous (Sevier) contractional tectonics; on this field trip we will see some of the field evidence on which this conclusion is based. -

Hydrologic Reconnaissance of the Blue Creek Valley Area, Box Elder County, Utah

STATE OF UTAH DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Technical Publication No. 37 HYDROLOGIC RECONNAISSANCE OF THE BLUE CREEK VALLEY AREA, BOX ELDER COUNTY, UTAH by E. L. Boike and Don Price, Hydrologists U. S. Geological Survey Prepared by the U. S. Geological Survey in cooperation with the Utah Department of Natural Resources Division of Water Rights 1972 CONTENTS Page Abstract. .. 1 Introduction . 1 Purpose and scope . 1 Description of the area . 1 Acknowledgments and previous studies . 1 Geology. .......... .3 Water resources .4 Volume of precipitation .4 Surface water . 7 Ground water 10 Recharge . 10 Occurrence and movement 10 Discharge ....... 11 Springs and seeps . 11 Evapotranspiration 12 Pumpage ...... 12 Ground-water outflow 12 Water-level fluctuations 12 Storage 13 Budget 14 Perennial yield 14 Chemical quality of water 14 Chemical quality in relation to use 15 Summary of water use ..... 16 Past and present development 16 Future development ... 18 Proposals for future studies. 18 References cited 19 Appendix .... 21 Well- and spring-numbering system . 22 Use of metric units . 22 Basic data ....... 25 Reports of reconnaissance water-resources investigations in selected basins of western Utah . 32 Publications of the Utah Department of Natural Resources, Division of Water Rights '" . 33 III ILLUSTRATIONS Page Plate 1. Hydrogeologic maps of the Blue Creek Valley area, Box Elder County, Utah .. In pocket Figure 1. Map showing location of the Blue Creek Valley area and of other areas described in previously published reports in this reconnaissance series ..... .2 2. Graph showing magnitude and frequency of annual peak discharges for Blue Creek .. 9 3. Graphs showing depth to water in wells in the Blue Creek Valley area and cumulative departure from normal annual (1931-60) precipitation at Malad, Idaho. -

Over the Range

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2008 Over the Range Richard V. Francaviglia Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Francaviglia, R. V. (2008). Over the range: A history of the Promontory Summit route of the Pacific ailrr oad. Logan: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Over the Range Photo by author Photographed at Promontory, Utah, in 2007, the curving panel toward the rear of Union Pacifi c 119’s tender (coal car) shows the colorful and ornate artwork incorporated into American locomotives in the Victorian era. Over the Range A History of the Promontory Summit Route of the Pacifi c Railroad Richard V. Francaviglia Utah State University Press Logan, Utah Copyright ©2008 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322-7200 www.usu.edu/usupress Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on recycled, acid-free paper ISBN: 978-0-87421-705-6 (cloth) ISBN: 978-0-87421-706-3 (e-book) Manufactured in China Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Francaviglia, Richard V. Over the range : a history of the Promontory summit route of the Pacifi c / Richard V. Francaviglia. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-87421-705-6 (cloth : alk. -

Appendix F3.12 Rangelands and Grazing

Appendix F3.12 Rangelands and Grazing BLM June 2011 Appendix F3.12 Table of Contents Figure F3.12-1 Grazing Allotments Table F3.12-1 Grazing Allotments Located Within the ROWs/Groundwater Development Areas for the Proposed Action Table F3.12-2 Springs in Area of Potential Impact per Grazing Allotments by Time Period Table F3.12-3 Sum of Miles of Perennial and Ephemeral Streams within the Area of Drawdown 10-foot or Greater Table F3.12-4 Sum of Acres by Drawdown of Greater than 10-foot to Wetland/Meadow and Basin Shrubland Vegetation Table F3.12-5 Cumulative Alternatives Comparison Carlin West Wendover Battle Mountain 196 306 228 144 ALT 93 93 55 22 Elko County 218 100 White Pine County 14 87 349 36 278 311 128 173 88 Tooele County 13 2 362 34 DEEP 382 Callao Juab County 489 335 278 147 CREEK 277 207 VALLEY Lander 113 256 County 177 FISH 130 211 SPRINGS STEPTOE 208 120 FLAT VALLEY 160 380 86 893 165 291 17 132 352 205 Juab County 892 96 93 101 180 191 198 68 126 Millard County 211 136 Eureka 78 Austin 61 390 199 SPRING 67 11 382 VALLEY 289 299 McGill 284 96 85 66 122 283 381 50 486 203 332 80 TULE VALLEY 82 365 47 219 197 6 Opt. 1 364 329 Ely 143 309 258 211 38 211 Eureka SNAKE VALLEY 270 County 211 209 211 70 351 102 189 327 326 172 Eskdale 282 83 204 365 12 6 56 108 212 White Pine County 487 159 119 240 255 224 43 Baker Nye County 228 211 125 112 8 Garrison 69 46 161 175 179 280 257 168 358 231 35 Opt. -

Hydrogeology of Spring, Cave, Dry Lake, and Delamar Valleys Impacts

HYDROGEOLOGY OF SPRING, CAVE, DRY LAKE, AND DELAMAR VALLEYS IMPACTS OF DEVELOPING SOUTHERN NEVADA WATER AUTHORITY’S CLARK, LINCOLN, AND WHITE PINE COUNTIES GROUNDWATER DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Presented to the Office of the Nevada State Engineer on behalf of Protestants White Pine County, Great Basin Water Network, et al. June, 2017 Prepared by: _______________________________________________________________ Thomas Myers, Ph.D. Hydrologic Consultant Reno, NV June 28, 2017 Date Table of Contents Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Method of Analysis .................................................................................................................................. 3 Study Area ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Water Rights Applications and Proposed Pumping Scenarios ............................................................... 8 Conceptual Flow Model ..................................................................................................................... 10 White River Flow System ................................................................................................................... 25 Hydrogeologic Properties of Aquifer Systems -

Biological Monitoring Plan for the Spring Valley Stipulation

Biological Monitoring Plan for the Spring Valley Stipulation Photo by Kelly Douglas February 2009 Biological Work Group Stipulation Parties: Bureau of Indian Affairs Bureau of Land Management National Park Service Southern Nevada Water Authority U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Invited Parties: Nevada Department of Wildlife Utah Division of Wildlife Resources Technical assistance in the preparation of this document was provided by: Bio-West, Inc., Logan, Utah Great Basin Bird Observatory, Reno, Nevada KS2 Ecological Field Services LLC, Anton, Texas The Nature Conservancy, Reno, Nevada This document may be cited as: Biological Work Group. 2009. Biological Monitoring Plan for the Spring Valley Stipulation. February 2009. LIST OF ACRONYMS ANOVA Analysis of Variance ANS Aquatic Nuisance Species BIA Bureau of Indian Affairs BLM Bureau of Land Management BWG Biological Work Group CAP Conservation Action Planning CCC Civilian Conservation Corps CPUE Catch Per Unit Effort DMP Data Management Plan DMS Document Management Software DOI Department of the Interior EC Executive Committee EPA Environmental Protection Agency EPT Ephemeroptera Plecoptera Trichoptera ESA Endangered Species Act FWS Fish and Wildlife Service GBNP Great Basin National Park GPS Global Positioning System HACCP Hazardous Analysis and Critical Control Points HB Hydrographic Basin IBMA Initial Biological Monitoring Area ICH Ichthiopterius (fish bacteria) LVVWD Las Vegas Valley Water District KEA Key Ecological Attribute MODFLOW Modular Three-Dimensional Finite-Difference Groundwater