Searching for the Haiku in Translation Sarah Macneil Under The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free Software an Introduction

Free Software an Introduction By Steve Riddett using Scribus 1.3.3.12 and Ubuntu 8.10 Contents Famous Free Software...................................................... 2 The Difference.................................................................. 3 Stallman and Torvalds.......................................................4 The Meaning of Distro......................................................5 Linux and the Holy Grail.................................................. 6 Frequently Asked Questions............................................. 7 Where to find out more.....................................................8 2 Free Software - an Introduction Famous Free Software Firefox is a web browser similar to Microsoft's Internet Explorer but made the Free software way. The project started in 2003 from the source code of the Netscape browser which had been released when Netscape went bust. In April 2009, Firefox recorded 29% use worldwide (34% in Europe). Firefox is standards compliant and has a system of add-ons which allow innovative new features to be added by the community. OpenOffice.org is an office suite similar to Microsoft Office. It started life as Star Office. Sun Microsystems realised it was cheaper to buy out Star Office than to pay Microsoft for licence fees for MS Office. Sun then released the source code for Star Office under the name OpenOffice.org. OpenOffice.org is mostly compatible with MS Office file formats, which allows users to open .docs and .xls files in Open Office. Microsoft is working on a plug-in for MS Office that allows it to open .odf files. ODF (Open Document Format) is Open Office's default file format. Once this plug-in is complete there will 100% compatiblity between the two office suites. VLC is the VideoLAN Client. It was originally designed to allow you to watch video over the network. -

Acadiens and Cajuns.Indb

canadiana oenipontana 9 Ursula Mathis-Moser, Günter Bischof (dirs.) Acadians and Cajuns. The Politics and Culture of French Minorities in North America Acadiens et Cajuns. Politique et culture de minorités francophones en Amérique du Nord innsbruck university press SERIES canadiana oenipontana 9 iup • innsbruck university press © innsbruck university press, 2009 Universität Innsbruck, Vizerektorat für Forschung 1. Auflage Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Umschlag: Gregor Sailer Umschlagmotiv: Herménégilde Chiasson, “Evangeline Beach, an American Tragedy, peinture no. 3“ Satz: Palli & Palli OEG, Innsbruck Produktion: Fred Steiner, Rinn www.uibk.ac.at/iup ISBN 978-3-902571-93-9 Ursula Mathis-Moser, Günter Bischof (dirs.) Acadians and Cajuns. The Politics and Culture of French Minorities in North America Acadiens et Cajuns. Politique et culture de minorités francophones en Amérique du Nord Contents — Table des matières Introduction Avant-propos ....................................................................................................... 7 Ursula Mathis-Moser – Günter Bischof des matières Table — By Way of an Introduction En guise d’introduction ................................................................................... 23 Contents Herménégilde Chiasson Beatitudes – BéatitudeS ................................................................................................. 23 Maurice Basque, Université de Moncton Acadiens, Cadiens et Cajuns: identités communes ou distinctes? ............................ 27 History and Politics Histoire -

Frogpond 37.1 • Winter 2014 (Pdf)

F ROGPOND T HE JOURNAL OF THE HAIKU SOCIETY OF AMERICA V OLUME 37:1 W INTER 2014 About HSA & Frogpond Subscription / HSA Membership: For adults in the USA, $35; in Canada/Mexico, $37; for seniors and students in North America, $30; for everyone elsewhere, $47. Pay by check on a USA bank or by International Postal Money Order. All subscriptions/memberships are annual, expiring on December 31, and include three issues of Frogpond as well as three newsletters, the members’ anthology, and voting rights. All correspondence regarding new and renewed memberships, changes of address, and requests for information should be directed to the HSA secretary (see the list of RI¿FHUVS). Make checks and money orders payable to Haiku Society of America, Inc. Single Copies of Back Issues: For USA & Canada, $14; for elsewhere, $15 by surface and $20 by airmail. Older issues might cost more, depending on how many are OHIW3OHDVHLQTXLUH¿UVW0DNHFKHFNVSD\DEOHWR+DLNX6RFLHW\RI America, Inc. Send single copy and back issue orders to the Frogpond editor (see p. 3). Contributor Copyright and Acknowledgments: All prior copyrights are retained by contributors. Full rights revert to contributors upon publication in Frogpond. Neither the Haiku 6RFLHW\RI$PHULFDLWVRI¿FHUVQRUWKHHGLWRUDVVXPHUHVSRQVLELOLW\ IRUYLHZVRIFRQWULEXWRUV LQFOXGLQJLWVRZQRI¿FHUV ZKRVHZRUNLV printed in Frogpond, research errors, infringement of copyrights, or failure to make proper acknowledgments. Frogpond Listing and Copyright Information: ISSN 8755-156X Listed in the MLA International Bibliography, Humanities Interna- tional Complete, Poets and Writers. © 2014 by the Haiku Society of America, Inc. Francine Banwarth, Editor Michele Root-Bernstein, Associate Editor Cover Design and Photos: Christopher Patchel. -

Acadian Music As a Cultural Symbol and Unifying Factor

L’Union Fait la Force: Acadian Music as a Cultural Symbol and Unifying Factor By Brooke Bisson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Atlantic Canada Studies at Saint Mary's University Halifax, Nova Scotia A ugust 27, 2003 I Brooke Bisson Approved By: Dr. J(Jihn Rgid Co-Supervisor Dr. Barbara LeBlanc Co-Supervisor Dr. Ma%aret Harry Reader George'S Arsenault Reader National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1^1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisisitons et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 0-612-85658-5 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 0-612-85658-5 The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of theL'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither thedroit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from Niit la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou aturement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. In compliance with the Canadian Conformément à la loi canadienne Privacy Act some supporting sur la protection de la vie privée, forms may have been removed quelques formulaires secondaires from this dissertation. -

Software Process Versus Design Quality: Tug of War? > Architecture Haiku > Designing Resource-Aware Cloud Applications

> Software Process versus Design Quality: Tug of War? > Architecture Haiku > Designing Resource-Aware Cloud Applications AUGUST 2015 www.computer.org IEEE COMPUTER SOCIETY http://computer.org • +1 714 821 8380 STAFF Editor Manager, Editorial Services Content Development Lee Garber Richard Park Senior Manager, Editorial Services Contributing Editors Robin Baldwin Christine Anthony, Brian Brannon, Carrie Clark Walsh, Brian Kirk, Chris Nelson, Meghan O’Dell, Dennis Taylor, Bonnie Wylie Director, Products and Services Evan Butterfield Production & Design Carmen Flores-Garvey, Monette Velasco, Jennie Zhu-Mai, Senior Advertising Coordinator Mark Bartosik Debbie Sims Circulation: ComputingEdge is published monthly by the IEEE Computer Society. IEEE Headquarters, Three Park Avenue, 17th Floor, New York, NY 10016-5997; IEEE Computer Society Publications Office, 10662 Los Vaqueros Circle, Los Alamitos, CA 90720; voice +1 714 821 8380; fax +1 714 821 4010; IEEE Computer Society Headquarters, 2001 L Street NW, Suite 700, Washington, DC 20036. Postmaster: Send undelivered copies and address changes to IEEE Membership Processing Dept., 445 Hoes Lane, Piscataway, NJ 08855. Application to Mail at Periodicals Postage Prices is pending at New York, New York, and at additional mailing offices. Canadian GST #125634188. Canada Post Corporation (Canadian distribution) publications mail agreement number 40013885. Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to PO Box 122, Niagara Falls, ON L2E 6S8 Canada. Printed in USA. Editorial: Unless otherwise stated, bylined articles, as well as product and service descriptions, reflect the author’s or firm’s opinion. Inclusion in ComputingEdge does not necessarily constitute endorsement by the IEEE or the Computer Society. All submissions are subject to editing for style, clarity, and space. -

Programming UEFI for Dummies Or What I Have Learned While Tweaking Freepascal to Output UEFI Binaries

Programming UEFI for dummies Or What I have learned while tweaking FreePascal to output UEFI binaries UEFI ● Unified Extensible Firmware Interface ● Specification that define an abstract common interface over firmware ● For short : BIOS replacement What I will discuss ? ● Quick overview of existing UEFI toolchains ● Structure of UEFI executable files ● Structure of UEFI APIs ● Overview of features exposed by UEFI APIs ● Protocols ● Bonus feature... ● What’s next ? Disclaimer notice ● While very important, this presentation will not discuss any security issues of UEFI ● I assume SecureBoot is disabled to use what is presented here Existing toolchains ● Mainly two stacks – TianoCore EDK II – GNU-EFI ● From what I read – Tedious setup process (more than one package) – GNU-EFI is supposed simpler to use (not simple ;-) – Do not require a full cross compiler Binary structure of UEFI application ● Portable Executable binaries (PE32 or PE32+ for x86* and ARM CPUs) ● With a special subsystem code to recognize an UEFI application from a Windows binary – Applications ● EFI_APP (11) : bootloader, baremetal applications... – drivers ● EFI_BOOT (12) : filesystem... ● EFI_RUN (13) : available to OS at runtime UEFI application entry point ● EFI_MAIN( imageHandle: EFI_HANDLE; systemTable : PEFI_SYSTEM_TABLE): EFI_STATUS; ● Same calling convention as the corresponding Windows target ● CPU already in protected mode with flat memory model – On 64 bits, already in long mode – But only one CPU core initialized Overview of EFI_SYSTEM_TABLE ● Access to Input/output/error -

Programming with Haiku

Programming with Haiku Lesson 5 Written by DarkWyrm All material © 2010 DarkWyrm Let's take some time to put together all of the different bits of code that we've been learning about. Since the first lesson, we have examined the following topics: • Templates • Namespaces • Iterators • The C++ string class • The STL Associative containers: map, set, multimap, and multiset • The STL Sequential containers: vector, deque, and list • The STL Container Adapters: queue and priority_queue • C++ input and output streams, a.k.a cout and friends • Exceptions There is enough material here that a book could be written to get a good, strong understanding of effective use of the Standard Template Library and the Standard C++ Library. Expert use is not our goal for this context, but having a good working knowledge of these topics will help make our code better when writing applications for Haiku. Project: Reading Paladin Projects For those unfamiliar, Paladin is one of the Integrated Development Environments available for Haiku. It was designed to have an interface similar to BeIDE, which was the main IDE for BeOS back in the day. One feature that sets it apart from other IDEs for Haiku is that its unique project file format is a text file with a specific format. This makes it possible to easily migrate to and away from it. The format itself is relatively simple. Each file is a list of key/value entry pairs with one entry per line. This makes it possible to read and interpret the project file progressively. It also increases forward compatibility because new keys can be ignored by older versions of the program. -

Haiku, a Desktop You Can Still Learn From

Haiku, a desktop you can still learn from No, you didn't steal all our ideas yet ;-) François Revol [email protected] Haiku? ● Free Software Operating System ● Inspired by BeOS ● We use our own kernel & graphics server – Pros: We control the whole stack – Cons: Much harder porting Linux & X11 stuff ● C++ API The Haiku desktop inspiration ● Inherited from BeOS ● Goes waaay back! ● Oh look! A Dock! – Later changed to DeskBar Haiku genealogy ● Poke levenez.com � MacOS 2001 DevEd, MaxEd… BeOS DR1… PR1 … R4 R5.1 ZETA NewOS kernel Unix OpenBeOS Haiku R1? “This looks like 1990 stuff to me” ● Ok, no fancy bubblegum whizzbang ● But that’s faster � ● There’s more to it… Modern features in Haiku \o/ ● Some stuff BeOS didn’t have… ● Layout support ● L10n / I18n Multithreaded app design ● App has several messaging Looper threads – Main thread: BApplication – One thread per BWindow ● app_server – 1 drawing thread per window ● Pros: Responsiveness ● Cons: Correct app design is harder Replicants ● Apps can provide BViews to others ● Host not limited to Tracker – BeHappy doc browser X-ray navigation ● Saves lot of window opening/closing ● Also for Copy/Move Scripting API ● Handlers report supported suites – Not unrelated to Intents on Android � ● Provides GUI controls introspection Node monitoring ● Like inotify but 20y ago ● Yeah, well, Linux didn’t invent it � ● Kernel sends BMessage archives to looper (Extended) Attributes ● Typed ● Xattrs exist in *nix – XDG std but no common API ● Indexable – Each fs has its own – By the fs (no – Nobody cares updatedb…) -

Programming the Be Operating System

Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................................... vii 1. BeOS Programming Overview ............................................................. 1 Features of the BeOS ....................................................................................... 1 Structure of the BeOS ...................................................................................... 5 Software Kits and Their Classes ...................................................................... 7 BeOS Programming Fundamentals ............................................................... 13 BeOS Programming Environment ................................................................. 28 2. BeIDE Projects .......................................................................................... 31 Development Environment File Organization .............................................. 31 Examining an Existing BeIDE Project ........................................................... 34 Setting up a New BeIDE Project ................................................................... 47 HelloWorld Source Code ............................................................................... 65 3. BeOS API Overview ................................................................................ 75 Overview of the BeOS Software Kits ............................................................ 75 Software Kit Class Descriptions .................................................................... -

Quarantine Poetry

Quarantine Poetry A Gift of Joy and Laughter From Mead School’s Poetry Workshop To You March - June 2020 Syllabic Poems Syllabic poems are poems measured by the number of syllables. Haikus are syllabic poems, for instance. HAIKU - Haiku poems are early Japanese poetry that originated with the introduction of writing in Chinese characters, most likely in the fifth century, A.D. In the Japanese tradition, the poems were often sung and had a pattern of dance gestures. Topics common to haiku poetry include: nature, ceremonies, friends and acquaintances, beauty, love, and death. A haiku poem consists of 17 syllables written in three lines with a 5-7-5 syllable pattern. Variations include the: SENRYU - same as haiku but the topics are about politics, social satire, or irony. TANKA - 31 syllables in a five line pattern of 5-7-5-7-7 syllables. CINQUAIN - 22 syllables in a five line pattern of 2-4-6-8-2 syllables. Jade Moore Senryu: What now? Fire alarm rings In case of fire. But what If it is on fire? Haiku: I love spring I stand with the flowers Then my allergies greet us I really hate spring. Austin Shapiro A little birdy Feed me! Starts flying around the house Just give me food! Cat sees little bird I’ve been nothing but good Kitty jumps into the sky Hey human up there, I’m talking! Birdy goes bye bye, munch munch Meow meow! Smack, smack, smack, pillow! A small little frog I hit and hit and beat you with fluff Sitting right next to a dog Feathers everywhere In the creepy fog The bedroom becomes covered The floor is turned to whiteness Rain, rain, -

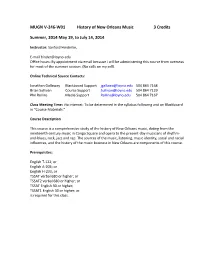

14SUM Syllabus NO Music

MUGN V-246-W01 History of New Orleans Music 3 Credits Summer, 2014 May 19, to July 14, 2014 Instructor: Sanford Hinderlie, E-mail [email protected] Office hours: By appointment via email because I will be administering this course from overseas for most of the summer session. (No calls on my cell). Online Technical Source Contacts: Jonathan Gallaway Blackboard Support [email protected] 504 864 7168 Brian Sullivan Course Support [email protected] 504 864 7129 Phil Rollins Media Support [email protected] 504 864 7167 Class Meeting Time: Via Internet: To be determined in the syllabus following and on Blackboard in “Course Materials.” Course Description This course is a comprehensive study of the history of New Orleans music, dating from the nineteenth century music in Congo Square and opera to the present-day musicians of rhythm- and-blues, rock, jazz and rap. The sources of the music, listening, music identity, social and racial influences, and the history of the music business in New Orleans are components of this course. Prerequisites: English T-122; or English A-205; or English H-233; or TSSAT verbal 680 or higher; or TSSAT2 verbal 680 or higher; or TSSAT English 30 or higher; TSSAT1 English 30 or higher; or is required for this class. Textbooks and Other Materials Purchased by Student: Armstrong, Louis. Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1954. Berry, Jason, Foose, Jonathan, and Jones, Tad. 2009 Up from the Cradle of Jazz, New Orleans Music since World War II, New Addition Edition. Lafayette, LA: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press. -

Technology Websites

Technology Websites 1. Animoto - Animoto is a video slideshow creator which allows users to upload images and use provided free songs. https://animoto.com/ 2. Anthologize - Anthologize is a plugin that turns WordPress into a platform for publishing electronic texts. http://anthologize.org/ 3. Bubblr – Create comic strips using photos found on flickr http://www.pimpampum.net/en/content/bubblr 4. BuddyPress - BuddyPress in a WordPress add-on that creates social networking features for use on your WP site. https://buddypress.org/ 5. Chatroll – Embed a chatroom into HTML or Canvas http://chatroll.com/ 6. ClassTools: Create free games, quizzes, activities and diagrams in seconds! Host them on your own blog, website or intranet! No signup, no passwords, no charge! http://www.classtools.net/ 7. ClippingMagic – ClippingMagic is a web-based way to crop parts of images with minimal time and effort (very impressive technology). https://clippingmagic.com/ 8. Coggle – Coggle helps sharing complex information by creating mind maps. www.coggle.it 9. Comic Life - Comic Life is a graphic illustrator / comic creating program. http://www.comiclife.com/ 10. Compfight - Compfight is a flikr search engine that locates Creative Commons licensed photos. http://compfight.com/ 11. Evernote - Evernote is a storage/bookmarking website that combines skitch, shoebox, and other software programs. https://evernote.com/ 12. Gigapan – very high resolution images enable online scrolling and zooming to approximate a digital field trip to many international and cultural locations. http://gigapan.com/ 13. Doodle – Scheduling and calendaring functions both in the cloud and integrated with outlook or google calendars http://doodle.com/ 14.