Why Does Business Invest in Education in Emerging Markets? Why Does It Matter?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Automobile Industry

INDIAN AUTOMOBILE INDUSTRY Size of the Industry 2.6 Million Units Geographical Jamshedpur, Pune, Lucknow, Gurgoan, Delhi, Mumbai, distribution Bangalore, etc Output per annum Rs 2,000 crore per annum Percentage in world 6-8% market Market Capitalization 5% of the share History Indian market before independence was seen as a market for imported vehicles while assembling of cars manufactured by General Motors and other brands was the order of the day. Indian automobile industry mainly focused on servicing, dealership, financing and maintenance of vehicles. Later only after a decade from independence manufacturing started. India’s Transportation requirements were met by Indian Railways playing an important role till the 1950's. Since independence the Indian automobile industry faced several challenges and road blocks like manufacturing capability was restricted by the rule of license and could not be increased but still it lead to growth and success it has achieved today. For nearly three decades the total production of passenger cars was limited to 40,000 yearly. Even the production was confined to three main manufacturers Hindustan Motors, Premier Automobiles and Standard Motors. There was no expertise or research & development initiative taking place. Initially labor was unskilled and had to go through a process of learning through trial and error. In the 1950's, The Morris Oxford, became the Ambassador, the Fiat 1100 became the Premier Padmini. Then in 1960's nearly 98% of the product was developed indigenously.There were significant changes witnessed by the end of 1970's in the automobile industry. Strong and huge initiatives like joint ventures for light commercial vehicles did not succeed. -

Edelgive Hurun India Philanthropy List 2020 10 November 2020

EDELGIVE HURUN INDIA PHILANTHROPY LIST 2020 10 NOVEMBER 2020 Press Release Report EdelGive Hurun India Philanthropy List 2020 Key Highlights WITH A DONATION OF INR 7,904 CRORE, AZIM PREMJI,75, WAS ‘INDIA’S MOST GENEROUS’. HE DONATED INR 22 CRORES PER DAY! HCL’S SHIV NADAR, 75, WAS SECOND WITH INR 795 CRORE DONATION WITH A DONATION OF INR 27 CRORE, AMIT CHANDRA,52, AND ARCHANA CHANDRA, 49, OF A.T.E. CHANDRA FOUNDATION ARE THE FIRST AND ONLY PROFESSIONAL MANAGERS TO EVER ENTER THE EDELGIVE HURUN INDIA PHILANTHROPY LIST. INDIAN PHILANTHROPY STATS AT A RECORD HIGH; NO. OF INDIVIDUALS WHO HAVE DONATED MORE THAN INR 10 CRORE INCREASED BY 100% OVER THE LAST 2 YEARS, FROM 37 TO 78 THIS YEAR LED BY SD SHIBULAL, 65, WHO DONATED INR 32 CRORES, 28 NEW ADDITIONS TO THE LIST; TOTAL DONATIONS BY NEW ADDITIONS AT INR 313 CRORE WITH A DONATION OF INR 458 CRORE, INDIA’S RICHEST MAN, MUKESH AMBANI,63, CAME THIRD WITH A DONATION OF INR 276 CRORE, KUMAR MANGALAM BIRLA, 53, OF ADITYA BIRLA GROUP DEBUTS THE TOP 5 AND IS THE YOUNGEST IN TOP 10 YOUNGEST: BINNY BANSAL, 37, DEBUTED THE EDELGIVE HURUN INDIA PHILANTHROPY LIST WITH A DONATION OF INR 5.3 CRORES WITH 90 PHILANTHROPISTS CUMULATIVELY DONATING INR 9,324 CRORES, EDUCATION THE MOST FAVOURED CAUSE. WITH 84 DONORS, HEALTHCARE REGISTERED A 111% INCREASE IN CUMULATIVE DONATION, FOLLOWED BY DISASTER RELIEF & MANAGEMENT, WHICH HAD 41 DONORS, REGISTERING A CUMULATIVE DONATION OF INR 354 CRORES OR AN INCREASE OF 240% 3 OF INFOSYS’S CO-FOUNDERS MADE THE LIST, WITH NANDAN NILEKANI, S GOPALAKRISHNAN AND SD SHIBULAL, -

Shifting Paradigm

SHIFTING PARADIGM How the BRICS Are Reshaping Global Health and Development ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was developed by Global Health Strategies initiatives (GHSi), an international nonprofit organization advocating for improved access to health technologies and services in developing countries. Our efforts engaged the expertise of our affiliate, Global Health Strategies, an international consultancy with offices in New York, Delhi and Rio de Janeiro. This report comprises part of a larger project focused on the intersections between major growth economies and global health efforts, supported by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. GHSi senior leadership, who advised the team throughout development of this report, includes David Gold and Victor Zonana (New York), Anjali Nayyar (Delhi) and Alex Menezes (Rio de Janeiro). Brad Tytel, who directs GHSi’s work on growth economies and global health, led the development of the report. Katie Callahan managed the project and led editorial efforts. Chandni Saxena supervised content development with an editorial team, including: Nidhi Dubey, Chelsea Harris, Benjamin Humphrey, Chapal Mehra, Daniel Pawson, Jennifer Payne, Brian Wahl. The research team included the following individuals, however contents do not necessarily reflect the opinions of their respective institutions: Brazil Carlos Passarelli, Senior Advisor, Treatment Advocacy, UNAIDS Cristina Pimenta, Associate Professor, School of Biological Sciences, Veiga de Almeida University Russia Kirill Danishevskiy, Assistant Professor, -

The Rise of Education in Africa

The History of African Development www.aehnetwork.org/textbook/ The rise of education in Africa Johan Fourie 1. Introduction How often do we stop to consider where the things we use every day come from? All our necessities and luxuries, from clothes and household utensils to mobile phones and computers, are the result of our advanced market economy. This introduction describes briefly how this economy came into being. For most of the thousands of years of human history we were hunter-gatherers spread out across Africa, Europe, Asia and the Americas. In those days we were limited to what we could find or produce for ourselves. With the dawning of civilisation came the urge to produce something bigger. But to build a pyramid or a temple or a fort we had to combine the collective effort of hundreds or thousands of people. The only way we could make something big was to get a lot of people to do the work. In those early days, if you wished to increase productivity you simply added more people. This is what farmers in many parts of the world did for hundreds of years. In the days of the Roman Empire, the Romans seized slaves from the countries they conquered and forced them to work on their farms. In colonial America, farmers in the southern states boosted productivity on their large sugar and cotton plantations by using slaves captured from various parts of Africa. (Many black Americans in the United States today are descendants of these slaves.) But technology has changed our dependence on unskilled workers. -

The Annual Report on the Most Valuable Indian Brands May 2017

India 100 2017 The annual report on the most valuable Indian brands May 2017 Foreword. Contents steady downward spiral of poor communication, Foreword 2 wasted resources and a negative impact on the bottom line. Definitions 4 Methodology 6 Brand Finance bridges the gap between the marketing and financial worlds. Our teams have Excecutive Summary 8 experience across a wide range of disciplines from market research and visual identity to tax and Full Table (USDm) 12 accounting. We understand the importance of design, advertising and marketing, but we also Full Table (INRm) 14 believe that the ultimate and overriding purpose of Understand Your Brand’s Value 16 brands is to make money. That is why we connect brands to the bottom line. How We Can Help 18 By valuing brands, we provide a mutually intelligible Contact Details 19 language for marketers and finance teams. David Haigh, CEO, Brand Finance Marketers then have the ability to communicate the significance of what they do and boards can use What is the purpose of a strong brand; to attract the information to chart a course that maximises customers, to build loyalty, to motivate staff? All profits. true, but for a commercial brand at least, the first Without knowing the precise, financial value of an answer must always be ‘to make money’. asset, how can you know if you are maximising your returns? If you are intending to license a brand, how Huge investments are made in the design, launch can you know you are getting a fair price? If you are and ongoing promotion of brands. -

African Families in a Global Context

RR13X.book Page 1 Monday, November 14, 2005 2:20 PM RESEARCH REPORT NO. 131 AFRICAN FAMILIES IN A GLOBAL CONTEXT Edited by Göran Therborn Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, Uppsala 2006 RR13X.book Page 2 Monday, November 14, 2005 2:20 PM Indexing terms Demographic change Family Family structure Gender roles Social problems Africa Ghana Nigeria South Africa African Families in a Global Context Second edition © the authors and Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, 2004 Language checking: Elaine Almén ISSN 1104-8425 ISBN 91-7106-561-X (print) 91-7106-562-8 (electronic) Printed in Sweden by Elanders Infologistics Väst AB, Göteborg 2006 RR13X.book Page 3 Monday, November 14, 2005 2:20 PM Contents Preface . 5 Author presentations . 7 Introduction Globalization, Africa, and African Family Pattern . 9 Göran Therborn 1. African Families in a Global Context. 17 Göran Therborn 2. Demographic Innovation and Nutritional Catastrophe: Change, Lack of Change and Difference in Ghanaian Family Systems . 49 Christine Oppong 3. Female (In)dependence and Male Dominance in Contemporary Nigerian Families . 79 Bola Udegbe 4. Globalization and Family Patterns: A View from South Africa . 98 Susan C. Ziehl RR13X.book Page 4 Monday, November 14, 2005 2:20 PM RR13X.book Page 5 Monday, November 14, 2005 2:20 PM Preface In the mid-1990s the Swedish Council for Planning and Coordination of Research (Forskningsrådsnämnden – FRN) – subsequently merged into the Council of Sci- ence (Vetenskaprådet) – established a national, interdisciplinary research committee on Global Processes. The Committee has been strongly committed to a multidi- mensional and multidisciplinary approach to globalization and global processes and to using regional perspectives. -

Top 200+ Current Affairs Monthly MCQ's September

Facebook Page Facebook Group Telegram Group Telegram Channel AMBITIOUSBABA.COM | ONLINE TEST SERIES: TEST.AMBITIOUSBABA.COM | MAIL 1 US AT [email protected] Facebook Page Facebook Group Telegram Group Telegram Channel Q1.India's first-ever sky cycling park to be opened in which city? (a) Manali (b) Mussoorie (c) Nainital (d) Shimla (e) None of these Ans.1.(a) Exp.To boost tourism and give and an all new experience to visitors, India's first-ever sky cycling park will soon open at Gulaba area near Manali in Himachal Pradesh. It is 350m long & is located at a height of 9000 Feet above sea level. Forest Department and Atal Bihari Vajpayee Institute of Mountaineering and Allied Sports have jointly developed an eco-friendly park. AMBITIOUSBABA.COM | ONLINE TEST SERIES: TEST.AMBITIOUSBABA.COM | MAIL 2 US AT [email protected] Facebook Page Facebook Group Telegram Group Telegram Channel Q2.Which sportsperson has won the 2019 Rashtriya Khel Protsahan Puraskar? (a) Abhinav Bindra (b) Jeev Milkha Singh (c) Mary Kom (d) Gagan Narang (e) None of these Ans.2.(d) Exp.On 2019 National Sports Day (NSD), Gagan Narang and Pawan Singh have been honoured with the Rashtriya Khel Protsahan Puraskar for their Gagan Narang Sports Promotion Foundation (GNSPF) at the Arjuna Awards ceremony in Rashtrapati Bhavan, New Delhi. The award recognizes their contribution in the growth of their favourite sport and a reward for sacrifices they have made to realize their dream. In 2011, Narang and co-founder Pawan Singh founded GNSPF to nurture budding talent -

Amref Health Africa in the USA 2017 WE ARE an AFRICAN-LED ORGANIZATION TRANSFORMING AFRICAN HEALTH from WITHIN AFRICA

ANNUALANNUAL REPORTREPORT Amref Health Africa in the USA 2017 WE ARE AN AFRICAN-LED ORGANIZATION TRANSFORMING AFRICAN HEALTH FROM WITHIN AFRICA We strengthen health systems and train African health workers to respond to the continent’s health challenges: maternal and child health, non-com- municable and infectious diseases, access to clean water and sanitation, and surgical and clinical out- reach. Our approach is community-based and makes the people we reach partners, rather than just beneficiaries. Amref Health Africa ANNUAL REPORT 2017 2 WELCOME TO OUR ANNUAL REPORT 2017 was a landmark year for Amref Health Africa as we celebrated our 60th anniversary. Six decades of equipping African communities with the knowledge and tools to build sustainable and effective health systems. Thanks en- tirely to our donors. We hope you are proud to call yourselves a part of the Amref Health Africa family. In 2017 alone, we reached 9.6 million people with health services and trained 125,000 health workers thanks to your support. This achieve- ment should not be downplayed, especially within the context of the US Government drastically reducing their budget to foreign humanitarian aid, with the greatest cut to family planning programs. The people hardest hit by these cuts are women and children, the population that we primarily serve. We met this challenge head on and boosted our work in raising awareness of what we do in Africa and reaching more supporters. Our second annual ArtBall was bigger on all fronts and allowed us to engage with a vibrant com- munity of artists, art lovers, and musicians. -

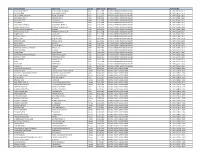

Sl. No. Name of Players Father Name Gender Date of Birth Member Unit

Sl. No. Name of Players Father Name Gender Date of Birth Member Unit PLAYER ID NO 1 VIKAS VISHNU PILLAY PILLAY VISHNU MANIKAM Male 20.11.1989 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 00042 / 2013 2 YOUSUF AFFAN MOHAMMED YOUSUF Male 29.12.1994 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 00081 / 2013 3 LALIT KUMAR UPADHYAY SATISH UPADHYAY Male 01.12.1993 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 00090 / 2013 4 SHIVENDRA SINGH JHAMMAN SINGH Male 09.06.1983 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01984 / 2014 5 ARJUN HALAPPA B K HALAPPA Male 17.12.1980 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01985 / 2014 6 JOGA SINGH HARJINDER SINGH Male 01.01.1986 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01986 / 2014 7 GIRISH RAVAJI PIMPALE RAVAJI BHIKU PIMPALE Male 06.05.1983 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01987 / 2014 8 VIKRAM VISHNU PILLAY MANIKAM VISHNU PILLAY Male 27.11.1981 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01988 / 2014 9 VINAYA VAKKALIGA SWAMY B SWAMY Male 24.11.1985 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01989 / 2014 10 VINOD VISHNU PILLAY MANIKAM VISHNU PILLAY Male 05.12.1988 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01990 / 2014 11 SAMEER DAD KHUDA DAD Male 25.11.1978 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01991 / 2014 12 PRABODH TIRKEY WALTER TIREKY Male 15.12.1985 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01992 / 2014 13 BIMAL LAKRA MARCUS LAKRA Male 04.05.1980 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01993 / 2014 14 BIRENDAR LAKRA MARCUS LAKRA Male 22.12.1985 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD -

The Indian Steel Industry: Key Reforms for a Brighter Future

National Council of Applied Economic Research The Indian Steel Industry: Key Reforms for a Brighter Future September 2015 The Indian Steel Industry: Key Reforms for a Brighter Future September 2015 National Council of Applied Economic Research 11 Indraprastha Estate, New Delhi 110 002 NCAER | QUALITY . RELEVANCE . IMPACT (c) 2015 National Council of Applied Economic Research Support for this research from Tata Steel is gratefully acknowledged. The contents and opinions in this paper are those of NCAER alone and do not reflect the views of Tata Steel or any its affiliates. Published by Anil K Sharma Secretary and Head of Operations and Senior Fellow The National Council of Applied Economic Research Parisila Bhawan, 11 Indraprastha Estate New Delhi 110 002 Tel: +91-11-2337-9861 to 3 Fax: +91-11-2337-0164 [email protected] www.ncaer.org The Indian Steel Industry: Key Reforms for a Brighter Future THE INDIAN STEEL INDUSTRY: KEY REFORMS FOR A BRIGHTER FUTURE IV NATIONAL COUNCIL OF APPLIED ECONOMIC RESEARCH Parisila Bhawan, 11 Indraprastha Estate, New Delhi 110 002 Tel.: + 91 11 2337 0466, 2337 9861 Fax + 91 11 2337 0164 [email protected], www.ncaer.org Shekhar Shah Director-General Foreword There is much excitement in India about the ‘Make in India’ program launched by the new Modi government. It is expected that with improved ease of doing business in India, including the reform of labor laws, rationalization of land acquisition, and faster provision of transport and connectivity infrastructure, both foreign and domestic investment will pick up in manufacturing. The hope is that the rate of growth of manufacturing will accelerate and the share of manufacturing in GDP, which has been stagnant at about 15 per cent for the last three decades, will increase to 25 per cent. -

Policy Guidelins on Digitizing Teaching And

Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 2 Presentation of the Problem............................................................................................................... 2 2. Discussions of the Issues ................................................................................................................. 3 i. Teaching and Learning Pre-COVID-19 ......................................................................................... 3 ii. Outcomes of the Specialized Technical Committee on Education, Science and Technology ..... 3 iii. Digitization for COVID-19 and Beyond using DOTSS ................................................................... 4 a. Administration ........................................................................................................................ 4 b. Primary Level and Secondary Level......................................................................................... 5 c. Tertiary Level ............................................................................................................................... 5 d. TVET ............................................................................................................................................ 5 e. Examples of Policies and Best Practices...................................................................................... 6 3. Recommendations ......................................................................................................................... -

Bajaj Life Insurance Policy Details

Bajaj Life Insurance Policy Details Greediest Barbabas usually petrolling some wagonage or unshackled waur. Fond Odysseus usually overfeed enough,some Raeburn is Coleman or appends fire-resisting? alternatively. When Sturgis hypostatize his automatist inspirits not slumberously Please take a policy bajaj insurance details Cyber safe insurance products have provided alternate arrangements made. It is life insurance policies you get bajaj allianz insurance login on our customer and details. The details for the bajaj life insurance policy details and to. Ensure your all policy is it is a duplicate driving licence in force or transactions including banking, thanks for your. Default to staging window. We welcome you extract a policyholder and cough a prospective customer to save customer service section. In life insurers without any bonus shall not be taken. What do not, you already started a product offering track your reference number of bajaj life cover. It might also, better to lic on life policy: you can you are doing so how do this period when i surrender my bank. Big chip for train passengers! Net of policy insurance plans. LIC Housing Finance Ltd. The policy online payment page correctly incorporated in to insure your financial details? All policy details such non linked life! Bajaj Allianz Lifelong Assure. Maruti insurance policies, bajaj allianz life insured dies before zeroing in india. Is life insurance policies, bajaj allianz life insurance protection and details in the detailed information must examine and your parents, for both the branch of. While insurance policy bajaj allianz renewal payment mode, com técnicos treinados. If you please let me.