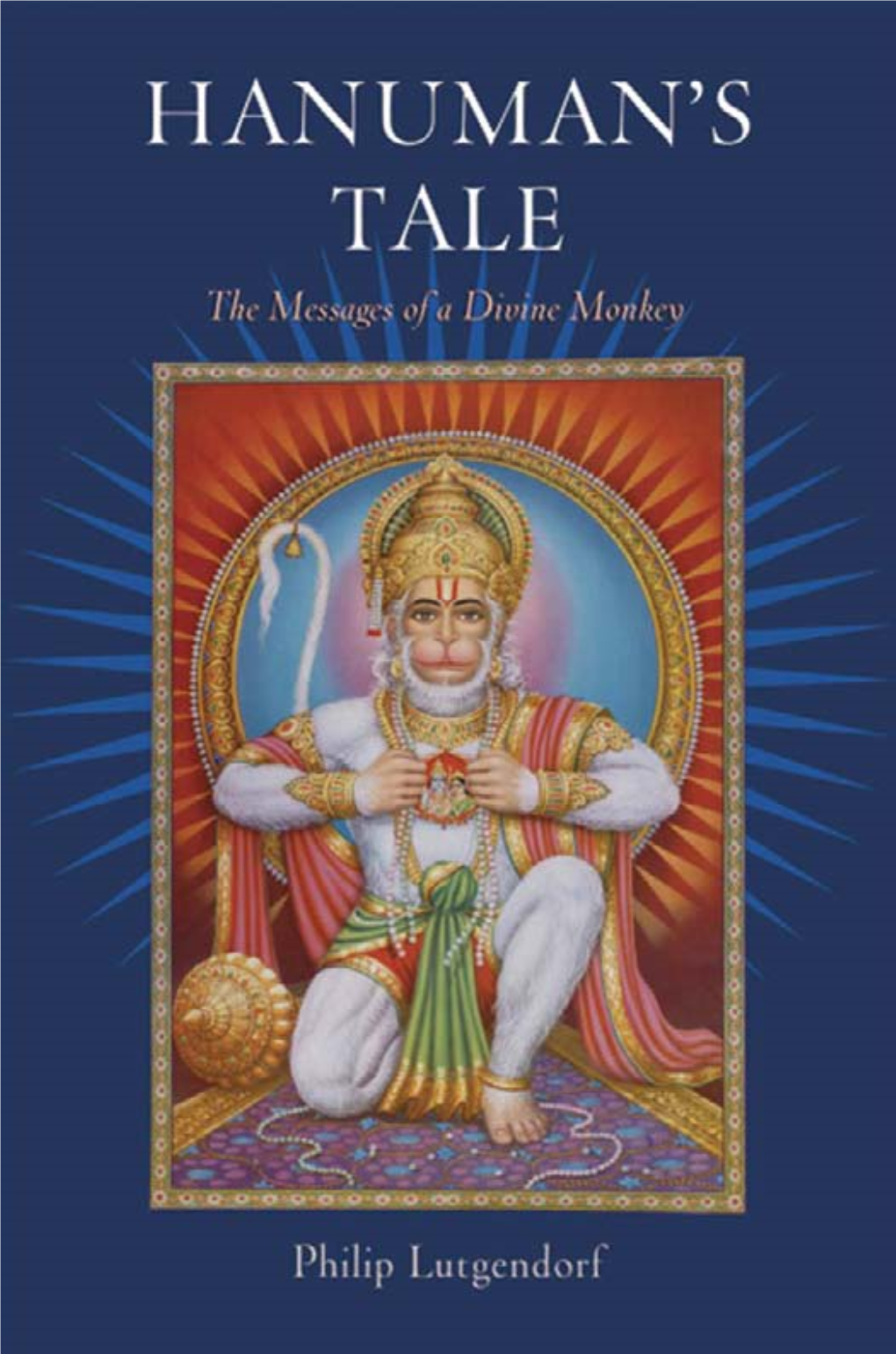

Philip Lutgendorf Hanumans Tal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

It 2.007 Vc Italian Films On

1 UW-Madison Learning Support Services Van Hise Hall - Room 274 rev. May 3, 2019 SET CALL NUMBER: IT 2.007 VC ITALIAN FILMS ON VIDEO, (Various distributors, 1986-1989) TYPE OF PROGRAM: Italian culture and civilization; Films DESCRIPTION: A series of classic Italian films either produced in Italy, directed by Italian directors, or on Italian subjects. Most are subtitled in English. Individual times are given for each videocassette. VIDEOTAPES ARE FOR RESERVE USE IN THE MEDIA LIBRARY ONLY -- Instructors may check them out for up to 24 hours for previewing purposes or to show them in class. See the Media Catalog for film series in other languages. AUDIENCE: Students of Italian, Italian literature, Italian film FORMAT: VHS; NTSC; DVD CONTENTS CALL NUMBER Il 7 e l’8 IT2.007.151 Italy. 90 min. DVD, requires region free player. In Italian. Ficarra & Picone. 8 1/2 IT2.007.013 1963. Italian with English subtitles. 138 min. B/W. VHS or DVD.Directed by Frederico Fellini, with Marcello Mastroianni. Fellini's semi- autobiographical masterpiece. Portrayal of a film director during the course of making a film and finding himself trapped by his fears and insecurities. 1900 (Novocento) IT2.007.131 1977. Italy. DVD. In Italian w/English subtitles. 315 min. Directed by Bernardo Bertolucci. With Robert De niro, Gerard Depardieu, Burt Lancaster and Donald Sutherland. Epic about friendship and war in Italy. Accattone IT2.007.053 Italy. 1961. Italian with English subtitles. 100 min. B/W. VHS or DVD. Directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini. Pasolini's first feature film. In the slums of Rome, Accattone "The Sponger" lives off the earnings of a prostitute. -

Ch. 3 MALE DEITIES I. Worship of Vishnu and Its Forms in Goa Vishnu

Ch. 3 MALE DEITIES I. Worship of Vishnu and its forms in Goa Vishnu is believed to be the Preserver God in the Hindu pantheon today. In the Vedic text he is known by the names like Urugai, Urukram 'which means wide going and wide striding respectively'^. In the Rgvedic text he is also referred by the names like Varat who is none other than says N. P. Joshi^. In the Rgvedhe occupies a subordinate position and is mentioned only in six hymns'*. In the Rgvedic text he is solar deity associated with days and seasons'. References to the worship of early form of Vishnu in India are found in inscribed on the pillar at Vidisha. During the second to first century BCE a Greek by name Heliodorus had erected a pillar in Vidisha in the honor of Vasudev^. This shows the popularity of Bhagvatism which made a Greek convert himself to the fold In the Purans he is referred to as Shripati or the husband oiLakshmi^, God of Vanmala ^ (wearer of necklace of wild flowers), Pundarikaksh, (lotus eyed)'". A seal showing a Kushan chief standing in a respectful pose before the four armed God holding a wheel, mace a ring like object and a globular object observed by Cunningham appears to be one of the early representations of Vishnu". 1. Vishnu and its attributes Vishnu is identified with three basic weapons which he holds in his hands. The conch, the disc and the mace or the Shankh. Chakr and Gadha. A. Shankh Termed as Panchjany Shankh^^ the conch was as also an essential element of Vishnu's identity. -

S. No. Name of the Ayurveda Medical Colleges

S. NO. NAME OF THE AYURVEDA MEDICAL COLLEGES Dr. BRKR Govt Ayurvedic CollegeOpp. E.S.I Hospital, Erragadda 1. Hyderabad-500038 Andhra Pradesh Dr.NR Shastry Govt. Ayurvedic College, M.G.Road,Vijayawada-520002 2. Urban Mandal, Krishna District Andhra Pradesh Sri Venkateswara Ayurvedic College, 3. SVIMS Campus, Tirupati North-517507Andhra Pradesh Anantha Laxmi Govt. Ayurvedic College, Post Laxmipura, Labour Colony, 4. Tq. & Dist. Warangal-506013 Andhra Pradesh Government Ayurvedic College, Jalukbari, Distt-Kamrup (Metro), 5. Guwahati- 781014 Assam Government Ayurvedic College & Hospital 6. Kadam Kuan, Patna 800003 Bihar Swami Raghavendracharya Tridandi Ayurved Mahavidyalaya and 7. Chikitsalaya,Karjara Station, PO Manjhouli Via Wazirganj, Gaya-823001Bihar Shri Motisingh Jageshwari Ayurved College & Hospital 8. Bada Telpa, Chapra- 841301, Saran Bihar Nitishwar Ayurved Medical College & HospitalBawan Bigha, Kanhauli, 9. P.O. RamanaMuzzafarpur- 842002 Bihar Ayurved MahavidyalayaGhughari Tand, 10. Gaya- 823001 Bihar Dayanand Ayurvedic Medical College & HospitalSiwan- 841266 11. Bihar Shri Narayan Prasad Awathy Government Ayurved College G.E. Road, 12. Raipur- 492001 Chhatisgarh Rajiv Lochan Ayurved Medical CollegeVillage & Post- 13. ChandkhuriGunderdehi Road, Distt. Durg- 491221 Chhatisgarh Chhatisgarh Ayurved Medical CollegeG.E. Road, Village Manki, 14. Dist.-Rajnandgaon 491441 Chhatisgarh Shri Dhanwantry Ayurvedic College & Dabur Dhanwantry Hospital 15. Plot No.-M-688, Sector 46-B Chandigarh- 160017 Ayurved & Unani Tibbia College and HospitalAjmal Khan Road, Karol 16. Bagh New Delhi-110005 Chaudhary Brahm Prakesh Charak Ayurved Sansthan 17. Khera Dabur, Najafgarh, New Delhi-110073 Bharteeya Sanskrit Prabodhini, Gomantak Ayurveda Mahavidyalaya & Research Centre, Kamakshi Arogyadham Vajem, 18. Shiroda Tq. Ponda, Dist. North Goa-403103 Goa Govt. Akhandanand Ayurved College & Hospital 19. Lal Darvaja, Bhadra Ahmedabad- 380001 Gujarat J.S. -

Bhagavata Purana

Bhagavata Purana The Bh āgavata Pur āṇa (Devanagari : भागवतपुराण ; also Śrīmad Bh āgavata Mah ā Pur āṇa, Śrīmad Bh āgavatam or Bh āgavata ) is one of Hinduism 's eighteen great Puranas (Mahapuranas , great histories).[1][2] Composed in Sanskrit and available in almost all Indian languages,[3] it promotes bhakti (devotion) to Krishna [4][5][6] integrating themes from the Advaita (monism) philosophy of Adi Shankara .[5][7][8] The Bhagavata Purana , like other puranas, discusses a wide range of topics including cosmology, genealogy, geography, mythology, legend, music, dance, yoga and culture.[5][9] As it begins, the forces of evil have won a war between the benevolent devas (deities) and evil asuras (demons) and now rule the universe. Truth re-emerges as Krishna, (called " Hari " and " Vasudeva " in the text) – first makes peace with the demons, understands them and then creatively defeats them, bringing back hope, justice, freedom and good – a cyclic theme that appears in many legends.[10] The Bhagavata Purana is a revered text in Vaishnavism , a Hindu tradition that reveres Vishnu.[11] The text presents a form of religion ( dharma ) that competes with that of the Vedas , wherein bhakti ultimately leads to self-knowledge, liberation ( moksha ) and bliss.[12] However the Bhagavata Purana asserts that the inner nature and outer form of Krishna is identical to the Vedas and that this is what rescues the world from the forces of evil.[13] An oft-quoted verse is used by some Krishna sects to assert that the text itself is Krishna in literary -

CEU Department of Medieval Studies Initiated Sessions at the 2003 and 2004 International Medieval Congresses in Connection with This Issue

ANNUAL OF MEDIEVAL STUDIES AT CEU VOL. 11 2005 Central European University Budapest ANNUAL OF MEDIEVAL STUDIES AT CEU VOL. 11 2005 Edited by Katalin Szende and Judith A. Rasson Central European University Budapest Department of Medieval Studies All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the permission of the publisher. Editorial Board János M. Bak, Gerhard Jaritz, Gábor Klaniczay, József Laszlovszky, Johannes Niehoff-Panagiotidis, István Perczel, Marianne Sághy Editors Katalin Szende and Judith A. Rasson Cover illustration Saint Sophia with Her Daughters from the Spiš region, ca. 1480–1490. Budapest, Hungarian National Gallery. Photo: Mihály Borsos Department of Medieval Studies Central European University H-1051 Budapest, Nádor u. 9., Hungary Postal address: H-1245 Budapest 5, P.O. Box 1082 E-mail: [email protected] Net: http://medstud.ceu.hu Copies can be ordered in the Department, and from the CEU Press http://www.ceupress.com/Order.html ISSN 1219-0616 Non-discrimination policy: CEU does not discriminate on the basis of—including, but not limited to—race, color, national or ethnic origin, religion, gender or sexual orientation in administering its educational policies, admissions policies, scholarship and loan programs, and athletic and other school-administered programs. © Central European University Produced by Archaeolingua Foundation & Publishing House TABLE OF CONTENTS Editors’ Preface ............................................................................................................. 5 I. ARTICLES AND STUDIES ......................................................................... 7 Magdolna Szilágyi Late Roman Bullae and Amulet Capsules in Pannonia ..................................... 9 Trpimir Vedriš Communities in Conflict: the Rivalry between the Cults of Sts. Anastasia and Chrysogonus in Medieval Zadar ...................................................................... -

Cinematic Urban Geographies Thursday 3 - Friday 4 October 2013 at CRASSH · Alison Richard Building · 7 West Road · Cambridge

Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities Cinematic Urban Geographies Thursday 3 - Friday 4 October 2013 at CRASSH · Alison Richard Building · 7 West Road · Cambridge Invited speakers CHARLOTTE BRUNSDON (Film Studies, University of Warwick) TERESA CASTRO (Universite Sorbonne Nouvelle - Paris 3) RICHARD COYNE (Architectural Computing, Edinburgh College of Art), ROLAND-FRANÇOIS LACK and (French Studies, UCL) STEVE PILE (Human Geography, The Open University) ANDREW PRESCOTT (Digital Humanities, King’s College London) MARK SHIEL (Film Studies, King’s College London) PETER VON BAGH (Film Historian and Director, Helsinki) Conveners FRANÇOIS PENZ (University of Cambridge) RICHARD KOECK (University of Liverpool) ANDREW SAINT (English Heritage) CHRIS SPEED (Edinburgh College of Art) www.crassh.cam.ac.uk/events/2473 Battersea Power Station and Nine Elms, 1966, Aerofilms Collection, English Heritatge 1966, Aerofilms and Nine Station Elms, Power Battersea Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities (CRASSH) Acknowledgements Supported by the Centre for Research in the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences (CRASSH), the Architecture Department, both at the University of Cambridge and the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC). Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities (CRASSH) | Alison Richard Building | 7 West Road Cambridge CB3 9DT | UK | www.crassh.cam.ac.uk Cinematic Urban Geographies Cinematic Urban Geographies 3 & 4 October 2013 at CRASSH (SG1&2) Conveners François Penz (Architecture Department, University of Cambridge) Co-Conveners Richard Koeck (School of Architecture, University of Liverpool) Chris Speed (Edinburgh College of Art) Andrew Saint (English Heritage) Summary The Cinematic Urban Geographies conference aims to explore the di!erent facets by which cinema and the moving image contribute to our understanding of cities and their topographies. -

AP Reports 229 Black Fungus Cases in 1

VIJAYAWADA, SATURDAY, MAY 29, 2021; PAGES 12 `3 RNI No.APENG/2018/764698 Established 1864 Published From VIJAYAWADA DELHI LUCKNOW BHOPAL RAIPUR CHANDIGARH BHUBANESWAR RANCHI DEHRADUN HYDERABAD *LATE CITY VOL. 3 ISSUE 193 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable www.dailypioneer.com New DNA vaccine for Covid-19 Raashi Khanna: Shooting abroad P DoT allocates spectrum P as India battled Covid P ’ effective in mice, hamsters 5 for 5G trials to telecom operators 8 was upsetting 12 In brief GST Council leaves tax rate on Delhi will begin AP reports 229 Black unlocking slowly from Monday, says Kejriwal Coronavirus vaccines unchanged n elhi will begin unlocking gradually fungus cases in 1 day PNS NEW DELHI from Monday, thanks to the efforts of the two crore people of The GST Council on Friday left D n the city which helped bring under PNS VIJAYAWADA taxes on Covid-19 vaccines and control the second wave, Chief medical supplies unchanged but Minister Arvind Kejriwal said. "In the The gross number of exempted duty on import of a med- past 24 hours, the positivity rate has Mucormycosis (Black fungus) cases icine used for treatment of black been around 1.5 per cent with only went up to 808 in Andhra Pradesh fungus. 1,100 new cases being reported. This on Friday with 229 cases being A group of ministers will delib- is the time to unlock lest people reported afresh in one day. erate on tax structure on the vac- escape corona only to die of hunger," “Lack of sufficient stock of med- cine and medical supplies, Finance Kejriwal said. -

Title Call # Category Lang./Notes

Title Call # Category Lang./Notes K-19 : the widowmaker 45205 Kaajal 36701 Family/Musical Ka-annanā ʻishrūn mustaḥīl = Like 20 impossibles 41819 Ara Kaante 36702 Crime Hin Kabhi kabhie 33803 Drama/Musical Hin Kabhi khushi kabhie gham-- 36203 Drama/Musical Hin Kabot Thāo Sīsudāčhan = The king maker 43141 Kabul transit 47824 Documentary Kabuliwala 35724 Drama/Musical Hin Kadının adı yok 34302 Turk/VCD Kadosh =The sacred 30209 Heb Kaenmaŭl = Seaside village 37973 Kor Kagemusha = Shadow warrior 40289 Drama Jpn Kagerōza 42414 Fantasy Jpn Kaidan nobori ryu = Blind woman's curse 46186 Thriller Jpn Kaiju big battel 36973 Kairo = Pulse 42539 Horror Jpn Kaitei gunkan = Atragon 42425 Adventure Jpn Kākka... kākka... 37057 Tamil Kakushi ken oni no tsume = The hidden blade 43744 Romance Jpn Kakushi toride no san akunin = Hidden fortress 33161 Adventure Jpn Kal aaj aur kal 39597 Romance/Musical Hin Kal ho naa ho 41312, 42386 Romance Hin Kalyug 36119 Drama Hin Kama Sutra 45480 Kamata koshin-kyoku = Fall guy 39766 Comedy Jpn Kān Klūai 45239 Kantana Animation Thai Kanak Attack 41817 Drama Region 2 Kanal = Canal 36907, 40541 Pol Kandahar : Safar e Ghandehar 35473 Farsi Kangwŏn-do ŭi him = The power of Kangwon province 38158 Kor Kannathil muthamittal = Peck on the cheek 45098 Tamil Kansas City 46053 Kansas City confidential 36761 Kanto mushuku = Kanto warrior 36879 Crime Jpn Kanzo sensei = Dr. Akagi 35201 Comedy Jpn Kao = Face 41449 Drama Jpn Kaos 47213 Ita Kaosu = Chaos 36900 Mystery Jpn Karakkaze yarô = Afraid to die 45336 Crime Jpn Karakter = Character -

Fairs and Festivals, (17 Karimnagar)

PRG. 179.17 (N) 750 KARIMNAGAR CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME II ANDHRA PRADESH PART VII - B (17) F AIRS AND FESTIV (17. Karimnagar District) A. CHANDRA SEKHAR OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Superintendent of Census Operations, Andhra Pradesh Price: Rs. 5.25 P. or 12 Sh. 3 d. or $ 1.89 c. 1961 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS, ANDHRA PRADESH (All the Census Publications of this State bear Vol. No. II) PART I-A (i) General Report (Chapters I to V) PART I-A (ii) General Report (Chapters VI to IX) PART I-A (iii) Gen'eral Report (Chapters eX to Xll) PART I-B Report on Vital Statistics PART I-C Subsidiary Tables PART II-A General Population Tables PART II-B (i) Economic Tables (B-1 to B-IV) PART II-B eii) Economic Tables (B-V to B-IX] PART II-C Cultural and Migration Tables PART III Household Economic Tables PART IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments (with Subsidiary Tables) PART IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables PART V-A Special Tables for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART VI Villag~ Survey Monographs (46) PART VII-A (1) l PART VlI-A (2) ~ ... Handicrafts Survey Reports (Selected Crafts) I PART VII-A (3) J PART VII-B (1 to 20) ... Fairs and Festivals (Separate Book for each District) PART VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration l }- (Not for sale) PART VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation J PART IX State Atlas PART X Special Report on Hyderabad City District Census Handbooks (Separate Volume for each District) I 1. -

On Space in Cinema

1 On Space in Cinema Jacques Levy Ecole polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne [email protected] Abstract The relationship between space and cinema is problematic. Cinema can be seen as a spatial art par excellence, but there are good reasons why this view is superficial. This article focuses on geographical films, which aim to increase our understanding of this dimension of the social world by attempting to depict inhabited space and the inhabitance of this space. The argument is developed in two stages. First, I attempt to show the absence both of space as an environment and of spatiality as an agency in cinematographic production. Both of these contribute to geographicity. Second, I put forward and expand on the idea of opening up new channels between cinema and the social sciences that take space as their object. This approach implies a move away from popular fiction cinema (and its avatar the documentary film) and an establishment of links with aesthetic currents from cinema history that are more likely to resonate with both geography and social science. The article concludes with a “manifesto” comprising ten principles for a scientific cinema of the inhabited space. Keywords: space, spatiality, cinema, history of cinema, diegetic space, distancing, film music, fiction, documentary, scientific films Space appears to be everywhere in film, but in fact it is (almost) nowhere. This observation leads us to reflect on the ways in which space is accommodated in films. I will focus in particular on what could be termed “geographical” films in the sense that they aim to increase our understanding of this dimension of the social world by 2 attempting to depict inhabited space and the inhabitance of this space. -

Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh

List of Coconut Producers Societies - Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh Sl. No CPS Name and Address Contact Address(president) Phone Nos Sri Sindhu Coconut Producers Society, Vajja Ravikumar, Balliputtuga Village, Sri Balliputtuga Village, Kusumpuram PO, Sindhu Coconut Producers Society, 1 9494588922 Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh-532292, Kaviti Kusumpuram PO, Kaviti Mandal, Srikakulam, Mandal Andhra Pradesh-532292 Sri Surya Coconut Producers Society, Pullata Kusaraju, Bhyripuram Village, Sri Bhyripuram Village, Rajapuram PO, Surya Coconut Producers Society, 2 9493909444 Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh-532312, Kaviti Rajapuram PO, Kaviti Mandal, Srikakulam, Mandal Andhra Pradesh-532312 Sri Laxminarasimha Coconut Producers Brindavan Dolai, Balliputtuga Village, Sri Society, Balliputtuga Village, Kusumpuram Laxminarasimha Coconut Producers Society, 3 9000646546 PO, Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh-532292, Kusumpuram PO, Kaviti Mandal, Srikakulam, Kaviti Mandal Andhra Pradesh-532292 Sri Jayabhavani Coconut Producers Ballada Jayaram, Bhyripuram Village, Sri Society, Bhyripuram Village, Rajapuram Jayabhavani Coconut Producers Society, 4 9866590732 PO, Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh-532312, Rajapuram PO, Kaviti Mandal, Srikakulam, Kaviti Mandal Andhra Pradesh-532312 Keta Laxminarayana, Kusumpuram Village & Sri Ganga Coconut Producers Society, PO, Sri Ganga Coconut Producers Society, 5 Kusumpuram Village & PO, , Srikakulam, 8008488891 Kaviti Mandal, Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh- Andhra Pradesh-532292, Kaviti Mandal 532292 Yarra Basudev, Govindaputtuga Village, Jai Jai Hanuman