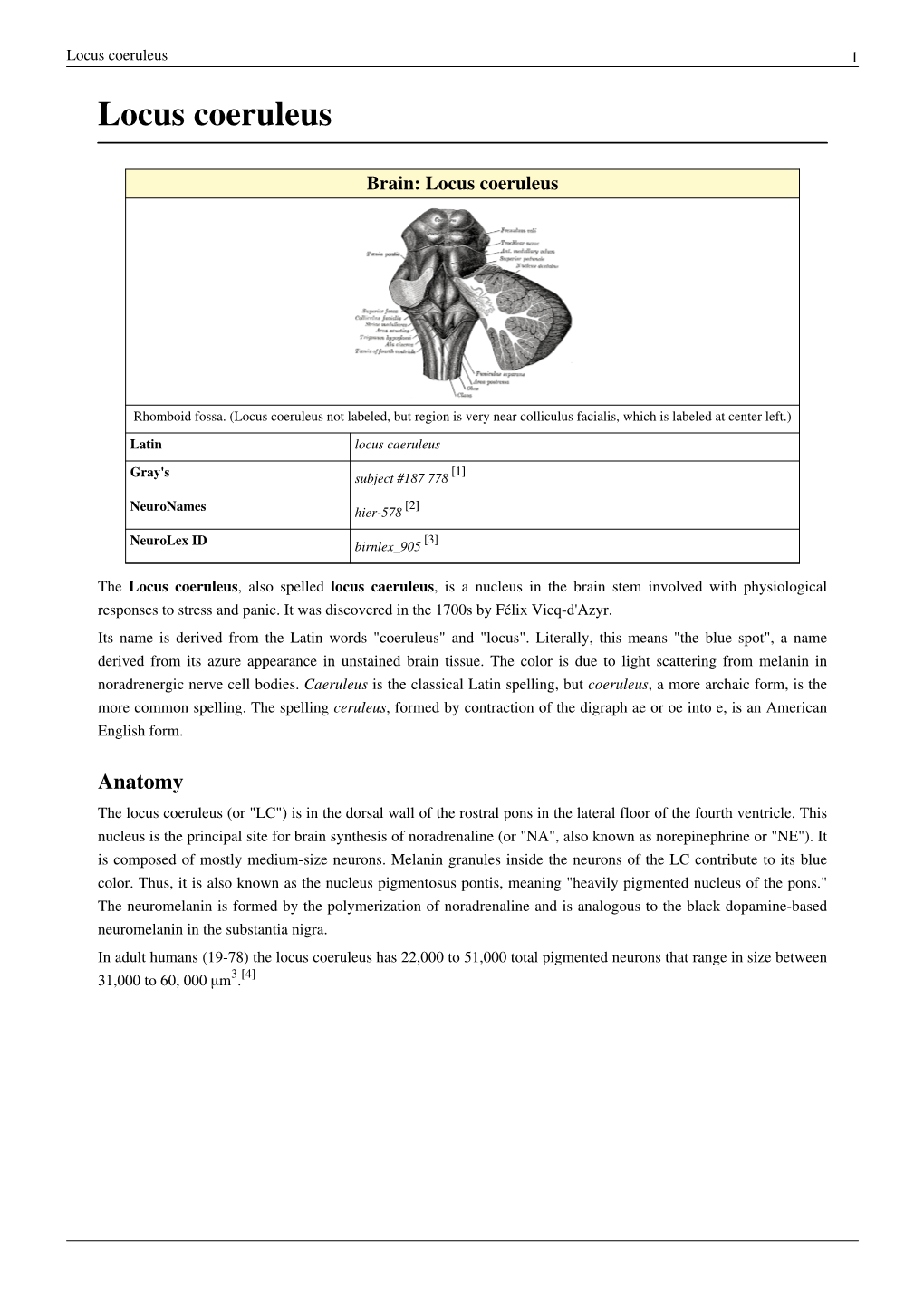

Locus Coeruleus 1 Locus Coeruleus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Role of Endoscopy in Management of Hydrocephalus

8 Role of Endoscopy in Management of Hydrocephalus Nasser M. F. El-Ghandour Department of Neurosurgery, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University Egypt 1. Introduction Management of hydrocephalus is the most beneficial indication for endoscopy. To cure hydrocephalus and thereby render an individual shunt independent is a great achievement. The standard and the most commonly performed endoscopic procedure is endoscopic third ventriculostomy. However, the field of neuroendoscopy is prepared to extend itself beyond just the ventriculostomy procedure. The neuroendoscope plays other important roles in the management of hydrocephalus. Although the literature is focusing mainly on the role of endoscopic third ventriculostomy in the treatment of aqueduct stenosis, the indications for endocopy continues to increase rapidly. With increasing experience, and improved endoscopic instruments, another important role of endoscopy has been emerged in approaching intraventricular tumors which may be completely removed without microsurgical brain dissection (Gaab & Schroeder, 1998). In addition to tumor removal it is usually possible to restore obstructed cerebrospinal fluid pathways using the same approach by performing ventriculostomies, septostomies or stent implantation (Oka et al., 1994). The goal of this chapter is to present the role of endoscopy in the management of hydrocephalus. The following chapter gives a comprehensive review about the indications, outcome, complications, and advantages of endoscopy. Various procedures which can be performed endoscopically for the management of hydrocephalus will be discussed. 2. Historical perspectives Endoscopy was introduced in the neurosurgical speciality at the beginning of this century. In 1910, L’Espinasse used the cystoscope to perform the first registered endoscopic procedure. He explored the lateral ventricle and coagulated the choroid plexus in 2 infants with hydrocephalus (Walker, 2001). -

Characterization of Age-Related Microstructural Changes in Locus Coeruleus and Substantia Nigra Pars Compacta

UC Riverside UC Riverside Previously Published Works Title Characterization of age-related microstructural changes in locus coeruleus and substantia nigra pars compacta. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/08304755 Journal Neurobiology of aging, 87 ISSN 0197-4580 Authors Langley, Jason Hussain, Sana Flores, Justino J et al. Publication Date 2020-03-01 DOI 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.11.016 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Neurobiology of Aging xxx (2019) 1e9 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Neurobiology of Aging journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/neuaging Characterization of age-related microstructural changes in locus coeruleus and substantia nigra pars compacta Jason Langley a, Sana Hussain b, Justino J. Flores c, Ilana J. Bennett c, Xiaoping Hu a,b,* a Center for Advanced Neuroimaging, University of California Riverside, Riverside, CA, USA b Department of Bioengineering, University of California Riverside, Riverside, CA, USA c Department of Psychology, University of California Riverside, Riverside, CA, USA article info abstract Article history: Locus coeruleus (LC) and substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) degrade with normal aging, but not Received 26 May 2019 much is known regarding how these changes manifest in MRI images, or whether these markers predict Received in revised form 19 November 2019 aspects of cognition. Here, we use high-resolution diffusion-weighted MRI to investigate microstructural Accepted 22 November 2019 and compositional changes in LC and SNpc in young and older adult cohorts, as well as their relationship with cognition. In LC, the older cohort exhibited a significant reduction in mean and radial diffusivity, but a significant increase in fractional anisotropy compared with the young cohort. -

Brainstem: Midbrainmidbrain

Brainstem:Brainstem: MidbrainMidbrain 1.1. MidbrainMidbrain –– grossgross externalexternal anatomyanatomy 2.2. InternalInternal structurestructure ofof thethe midbrain:midbrain: cerebral peduncles tegmentum tectum (guadrigeminal plate) Midbrain MidbrainMidbrain –– generalgeneral featuresfeatures location – between forebrain and hindbrain the smallest region of the brainstem – 6-7g the shortest brainstem segment ~ 2 cm long least differentiated brainstem division human midbrain is archipallian – shared general architecture with the most ancient of vertebrates embryonic origin – mesencephalon main functions:functions a sort of relay station for sound and visual information serves as a nerve pathway of the cerebral hemispheres controls the eye movement involved in control of body movement Prof. Dr. Nikolai Lazarov 2 Midbrain MidbrainMidbrain –– grossgross anatomyanatomy dorsal part – tectum (quadrigeminal plate): superior colliculi inferior colliculi cerebral aqueduct ventral part – cerebral peduncles:peduncles dorsal – tegmentum (central part) ventral – cerebral crus substantia nigra Prof. Dr. Nikolai Lazarov 3 Midbrain CerebralCerebral cruscrus –– internalinternal structurestructure CerebralCerebral peduncle:peduncle: crus cerebri tegmentum mesencephali substantia nigra two thick semilunar white matter bundles composition – somatotopically arranged motor tracts: corticospinal } pyramidal tracts – medial ⅔ corticobulbar corticopontine fibers: frontopontine tracts – medially temporopontine tracts – laterally -

Sex Differences in the Hypothalamic Oxytocin Pathway to Locus Coeruleus and Augmented Attention with Chemogenetic Activation of Hypothalamic Oxytocin Neurons

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Sex Differences in the Hypothalamic Oxytocin Pathway to Locus Coeruleus and Augmented Attention with Chemogenetic Activation of Hypothalamic Oxytocin Neurons Xin Wang, Joan B. Escobar and David Mendelowitz * Department of Pharmacology and Physiology, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, The George University Washington, Washington, DC 20037, USA; [email protected] (X.W.); [email protected] (J.B.E.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The tightly localized noradrenergic neurons (NA) in the locus coeruleus (LC) are well recognized as essential for focused arousal and novelty-oriented responses, while many children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) exhibit diminished attention, engagement and orienting to exogenous stimuli. This has led to the hypothesis that atypical LC activity may be involved in ASD. Oxytocin (OXT) neurons and receptors are known to play an important role in social behavior, pair bonding and cognitive processes and are under investigation as a potential treatment for ASD. However, little is known about the neurotransmission from hypothalamic paraventricular (PVN) OXT neurons to LC NA neurons. In this study, we test, in male and female rats, whether PVN OXT neurons excite LC neurons, whether oxytocin is released and involved in this neurotransmission, Citation: Wang, X.; Escobar, J.B.; and whether activation of PVN OXT neurons alters novel object recognition. Using “oxytocin sniffer Mendelowitz, D. Sex Differences in cells” (CHO cells that express the human oxytocin receptor and a Ca indicator) we show that there is the Hypothalamic Oxytocin Pathway release of OXT from hypothalamic PVN OXT fibers in the LC. Optogenetic excitation of PVN OXT to Locus Coeruleus and Augmented fibers excites LC NA neurons by co-release of OXT and glutamate, and this neurotransmission is Attention with Chemogenetic Activation of Hypothalamic Oxytocin greater in males than females. -

The Brain Stem Medulla Oblongata

Chapter 14 The Brain Stem Medulla Oblongata Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display. Central sulcus Parietal lobe • embryonic myelencephalon becomes Cingulate gyrus leaves medulla oblongata Corpus callosum Parieto–occipital sulcus Frontal lobe Occipital lobe • begins at foramen magnum of the skull Thalamus Habenula Anterior Epithalamus commissure Pineal gland • extends for about 3 cm rostrally and ends Hypothalamus Posterior commissure at a groove between the medulla and Optic chiasm Mammillary body pons Cerebral aqueduct Pituitary gland Fourth ventricle Temporal lobe • slightly wider than spinal cord Cerebellum Midbrain • pyramids – pair of external ridges on Pons Medulla anterior surface oblongata – resembles side-by-side baseball bats (a) • olive – a prominent bulge lateral to each pyramid • posteriorly, gracile and cuneate fasciculi of the spinal cord continue as two pair of ridges on the medulla • all nerve fibers connecting the brain to the spinal cord pass through the medulla • four pairs of cranial nerves begin or end in medulla - IX, X, XI, XII Medulla Oblongata Associated Functions • cardiac center – adjusts rate and force of heart • vasomotor center – adjusts blood vessel diameter • respiratory centers – control rate and depth of breathing • reflex centers – for coughing, sneezing, gagging, swallowing, vomiting, salivation, sweating, movements of tongue and head Medulla Oblongata Nucleus of hypoglossal nerve Fourth ventricle Gracile nucleus Nucleus of Cuneate nucleus vagus -

Corticotropin-Releasing Factor in the Norepinephrine Nucleus, Locus Coeruleus, Facilitates Behavioral Flexibility

Neuropsychopharmacology (2012) 37, 520–530 & 2012 American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. All rights reserved 0893-133X/12 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org Corticotropin-Releasing Factor in the Norepinephrine Nucleus, Locus Coeruleus, Facilitates Behavioral Flexibility Kevin Snyder1,4, Wei-Wen Wang2,4, Rebecca Han1, Kile McFadden3 and Rita J Valentino*,3 1 2 3 The University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA; Key Laboratory of Mental Health, Institute of Psychology, Beijing, China; Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, USA Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), the stress-related neuropeptide, acts as a neurotransmitter in the brain norepinephrine nucleus, locus coeruleus (LC), to activate this system during stress. CRF shifts the mode of LC discharge from a phasic to a high tonic state that is thought to promote behavioral flexibility. To investigate this, the effects of CRF administered either intracerebroventricularly (30–300 ng, i.c.v.) or directly into the LC (intra-LC; 2–20 ng) were examined in a rat model of attentional set shifting. CRF differentially affected components of the task depending on dose and route of administration. Intracerebroventricular CRF impaired intradimensional set shifting, reversal learning, and extradimensional set shifting (EDS) at different doses. In contrast, intra-LC CRF did not impair any aspect of the task. The highest dose of CRF (20 ng) facilitated reversal learning and the lowest dose (2 ng) improved EDS. The dose–response relationship for CRF on EDS performance resembled an inverted U-shaped curve with the highest dose having no effect. Intra-LC CRF also elicited c-fos expression in prefrontal cortical neurons with an inverted U-shaped dose–response relationship. -

Neuromelanin Marks the Spot: Identifying a Locus Coeruleus Biomarker of Cognitive Reserve in Healthy Aging

Neurobiology of Aging xxx (2015) 1e10 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Neurobiology of Aging journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/neuaging Neuromelanin marks the spot: identifying a locus coeruleus biomarker of cognitive reserve in healthy aging David V. Clewett a,*, Tae-Ho Lee b, Steven Greening b,c,d, Allison Ponzio c, Eshed Margalit e, Mara Mather a,b,c a Neuroscience Graduate Program, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA b Department of Psychology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA c Davis School of Gerontology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA d Department of Psychology, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA e Dornsife College of Letters and Sciences, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA article info abstract Article history: Leading a mentally stimulating life may build up a reserve of neural and mental resources that preserve Received 28 May 2015 cognitive abilities in late life. Recent autopsy evidence links neuronal density in the locus coeruleus (LC), Received in revised form 18 September 2015 the brain’s main source of norepinephrine, to slower cognitive decline before death, inspiring the idea Accepted 23 September 2015 that the noradrenergic system is a key component of reserve (Robertson, I. H. 2013. A noradrenergic theory of cognitive reserve: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 34, 298e308). Here, we tested this hypothesis using neuromelanin-sensitive magnetic resonance imaging to visualize and Keywords: measure LC signal intensity in healthy younger and older adults. Established proxies of reserve, including Locus coeruleus Aging education, occupational attainment, and verbal intelligence, were linearly correlated with LC signal in- fi Norepinephrine tensity in both age groups. -

The Choroid Plexus: a Comprehensive Review of Its History, Anatomy, Function, Histology, Embryology, and Surgical Considerations

Childs Nerv Syst (2014) 30:205–214 DOI 10.1007/s00381-013-2326-y REVIEW PAPER The choroid plexus: a comprehensive review of its history, anatomy, function, histology, embryology, and surgical considerations Martin M. Mortazavi & Christoph J. Griessenauer & Nimer Adeeb & Aman Deep & Reza Bavarsad Shahripour & Marios Loukas & Richard Isaiah Tubbs & R. Shane Tubbs Received: 30 September 2013 /Accepted: 11 November 2013 /Published online: 28 November 2013 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Abstract Keywords Choroid plexus . Anatomy . Neurosurgery . Introduction The role of the choroid plexus in cerebrospinal Hydrocephalus fluid production has been identified for more than a century. Over the years, more intensive studies of this structure has lead to a better understanding of the functions, including brain Introduction immunity, protection, absorption, and many others. Here, we review the macro- and microanatomical structure of the Around the walls of the ventricles, folds of pia mater form choroid plexus in addition to its function and embryology. vascularized layers named choroid plexus. This vasculature Method The literature was searched for articles and textbooks along with the overlying ependymal lining of the ventricles for data related to the history, anatomy, physiology, histology, forms the tela choroidea. Sometimes, however, the term embryology, potential functions, and surgical implications of choroid plexus is used to describe the entire structure [1]. The the choroid plexus. All were gathered and summarized narrow cleft, to which the choroids plexus is attached in the comprehensively. ventricles, is defined as the choroidal fissure. [2] The discovery Conclusion We summarize the literature regarding the choroid of the choroid plexus is attributed to Herophilus, who named it plexus and its surgical implications. -

High-Yield Neuroanatomy

LWBK110-3895G-FM[i-xviii].qxd 8/14/08 5:57 AM Page i Aptara Inc. High-Yield TM Neuroanatomy FOURTH EDITION LWBK110-3895G-FM[i-xviii].qxd 8/14/08 5:57 AM Page ii Aptara Inc. LWBK110-3895G-FM[i-xviii].qxd 8/14/08 5:57 AM Page iii Aptara Inc. High-Yield TM Neuroanatomy FOURTH EDITION James D. Fix, PhD Professor Emeritus of Anatomy Marshall University School of Medicine Huntington, West Virginia With Contributions by Jennifer K. Brueckner, PhD Associate Professor Assistant Dean for Student Affairs Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology University of Kentucky College of Medicine Lexington, Kentucky LWBK110-3895G-FM[i-xviii].qxd 8/14/08 5:57 AM Page iv Aptara Inc. Acquisitions Editor: Crystal Taylor Managing Editor: Kelley Squazzo Marketing Manager: Emilie Moyer Designer: Terry Mallon Compositor: Aptara Fourth Edition Copyright © 2009, 2005, 2000, 1995 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a Wolters Kluwer business. 351 West Camden Street 530 Walnut Street Baltimore, MD 21201 Philadelphia, PA 19106 Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. This book is protected by copyright. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including as photocopies or scanned-in or other electronic copies, or utilized by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the copyright owner, except for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Materials appearing in this book prepared by individuals as part of their official duties as U.S. government employees are not covered by the above-mentioned copyright. To request permission, please contact Lippincott Williams & Wilkins at 530 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106, via email at [email protected], or via website at http://www.lww.com (products and services). -

The Nucleus Prepositus Hypoglossi Contributes to Head Direction Cell Stability in Rats

The Journal of Neuroscience, February 11, 2015 • 35(6):2547–2558 • 2547 Systems/Circuits The Nucleus Prepositus Hypoglossi Contributes to Head Direction Cell Stability in Rats William N. Butler and XJeffrey S. Taube Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire 03755 Head direction (HD) cells in the rat limbic system fire according to the animal’s orientation independently of the animal’s environmental location or behavior. These HD cells receive strong inputs from the vestibular system, among other areas, as evidenced by disruption of their directional firing after lesions or inactivation of vestibular inputs. Two brainstem nuclei, the supragenual nucleus (SGN) and nucleus prepositus hypoglossi (NPH), are known to project to the HD network and are thought to be possible relays of vestibular information. Previous work has shown that lesioning the SGN leads to a loss of spatial tuning in downstream HD cells, but the NPH has historically been defined as an oculomotor nuclei and therefore its role in contributing to the HD signal is less clear. Here, we investigated this role by recording HD cells in the anterior thalamus after either neurotoxic or electrolytic lesions of the NPH. There was a total loss of direction-specific firing in anterodorsal thalamus cells in animals with complete NPH lesions. However, many cells were identified that fired in bursts unrelated to the animals’ directional heading and were similar to cells seen in previous studies that damaged vestibular- associated areas. Some animals with significant but incomplete lesions of the NPH had HD cells that were stable under normal conditions, but were unstable under conditions designed to minimize the use of external cues. -

High-Yield Neuroanatomy, FOURTH EDITION

LWBK110-3895G-FM[i-xviii].qxd 8/14/08 5:57 AM Page i Aptara Inc. High-Yield TM Neuroanatomy FOURTH EDITION LWBK110-3895G-FM[i-xviii].qxd 8/14/08 5:57 AM Page ii Aptara Inc. LWBK110-3895G-FM[i-xviii].qxd 8/14/08 5:57 AM Page iii Aptara Inc. High-Yield TM Neuroanatomy FOURTH EDITION James D. Fix, PhD Professor Emeritus of Anatomy Marshall University School of Medicine Huntington, West Virginia With Contributions by Jennifer K. Brueckner, PhD Associate Professor Assistant Dean for Student Affairs Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology University of Kentucky College of Medicine Lexington, Kentucky LWBK110-3895G-FM[i-xviii].qxd 8/14/08 5:57 AM Page iv Aptara Inc. Acquisitions Editor: Crystal Taylor Managing Editor: Kelley Squazzo Marketing Manager: Emilie Moyer Designer: Terry Mallon Compositor: Aptara Fourth Edition Copyright © 2009, 2005, 2000, 1995 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a Wolters Kluwer business. 351 West Camden Street 530 Walnut Street Baltimore, MD 21201 Philadelphia, PA 19106 Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. This book is protected by copyright. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including as photocopies or scanned-in or other electronic copies, or utilized by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the copyright owner, except for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Materials appearing in this book prepared by individuals as part of their official duties as U.S. government employees are not covered by the above-mentioned copyright. To request permission, please contact Lippincott Williams & Wilkins at 530 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106, via email at [email protected], or via website at http://www.lww.com (products and services). -

…Going One Step Further

…going one step further C20 (1017868) 2 Latin A Encephalon Mesencephalon B Telencephalon 31 Lamina tecti B1 Lobus frontalis 32 Tegmentum mesencephali B2 Lobus temporalis 33 Crus cerebri C Diencephalon 34 Aqueductus mesencephali D Mesencephalon E Metencephalon Metencephalon E1 Cerebellum 35 Cerebellum F Myelencephalon a Vermis G Circulus arteriosus cerebri (Willisii) b Tonsilla c Flocculus Telencephalon d Arbor vitae 1 Lobus frontalis e Ventriculus quartus 2 Lobus parietalis 36 Pons 3 Lobus occipitalis f Pedunculus cerebellaris superior 4 Lobus temporalis g Pedunculus cerebellaris medius 5 Sulcus centralis h Pedunculus cerebellaris inferior 6 Gyrus precentralis 7 Gyrus postcentralis Myelencephalon 8 Bulbus olfactorius 37 Medulla oblongata 9 Commissura anterior 38 Oliva 10 Corpus callosum 39 Pyramis a Genu 40 N. cervicalis I. (C1) b Truncus ® c Splenium Nervi craniales d Rostrum I N. olfactorius 11 Septum pellucidum II N. opticus 12 Fornix III N. oculomotorius 13 Commissura posterior IV N. trochlearis 14 Insula V N. trigeminus 15 Capsula interna VI N. abducens 16 Ventriculus lateralis VII N. facialis e Cornu frontale VIII N. vestibulocochlearis f Pars centralis IX N. glossopharyngeus g Cornu occipitale X N. vagus h Cornu temporale XI N. accessorius 17 V. thalamostriata XII N. hypoglossus 18 Hippocampus Circulus arteriosus cerebri (Willisii) Diencephalon 1 A. cerebri anterior 19 Thalamus 2 A. communicans anterior 20 Sulcus hypothalamicus 3 A. carotis interna 21 Hypothalamus 4 A. cerebri media 22 Adhesio interthalamica 5 A. communicans posterior 23 Glandula pinealis 6 A. cerebri posterior 24 Corpus mammillare sinistrum 7 A. superior cerebelli 25 Hypophysis 8 A. basilaris 26 Ventriculus tertius 9 Aa. pontis 10 A.