Costa's Hummingbird: Its Distribution and Status

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Attracting Hummingbirds to Your Garden Using Native Plants

United States Department of Agriculture Attracting Hummingbirds to Your Garden Using Native Plants Black-chinned Hummingbird feeding on mountain larkspur, fireweed, and wild bergamot (clockwise from top) Forest National Publication April Service Headquarters Number FS-1046 2015 Hummingbird garden guide Many of us enjoy the beauty of flowers in our backyard and community gardens. Growing native plants adds important habitat for hummingbirds and other wildlife—especially pollinators. Even small backyard gardens can make a difference. Gardening connects us to nature and helps us better understand how nature works. This guide will help you create a hummingbird- What do hummingbirds, friendly garden. butterflies, and bees have in common? They all pollinate flowering plants. Broad-tailed Hummingbird feeding on scarlet gilia Hummingbirds are Why use native plants in restricted to the Americas with more your garden? than 325 species of Hummingbirds have evolved with hummingbirds in North, Central, and native plants, which are best adapted South America. to local growing seasons, climate, and soil. They prefer large, tubular flowers that are often (but not always) red in color. In this guide, we feature seven hummingbirds that breed in the United States. For each one, we also highlight two native plants found in its breeding range. These native plants are easy to grow, need little water once established, and offer hummingbirds abundant nectar. 2 Hummingbirds and pollination Ruby-throated Hummingbird feeding on the At rest, a hummer’s nectar and pollen heart beats an of blueberry flowers average of 480 beats per minute. On cold nights, it goes into What is pollination? torpor (hibernation- like state), and its Pollination is the process of moving pollen heart rate drops to (male gamete) from one flower to the ovary of another 45 to 180 beats per minute. -

Paper Describing Hummingbird-Sized Dinosaur Retracted 24 July 2020, by Bob Yirka

Paper describing hummingbird-sized dinosaur retracted 24 July 2020, by Bob Yirka teeth. Some in the field were so sure that it was a lizard and not a dinosaur that they wrote and uploaded a paper to the bioRxiv preprint server outlining their concerns. The authors of the paper then published a response addressing their concerns and refuting the skeptics' arguments. That was followed by another team reporting that they had found a similar fossil and after studying it, had deemed it to be a lizard. In reviewing both the paper and the evidence presented by others in the field, the editors at Nature chose to retract the paper. A CT scan of the skull of Oculudentavis by LI Gang, The researchers who published the original paper Oculudentavis means eye-tooth-bird, so named for its appear to be divided on their assessment of the distinctive features. Credit: Lars Schmitz retraction, with some insisting there was no reason for the paper to be retracted and others acknowledging that they had made a mistake when they classified their find as a dinosaur. In either The journal Nature has issued a retraction for a case, all of the researchers agree that the work paper it published March 11th called they did on the fossil was valid and thus the paper "Hummingbird-sized dinosaur from the Cretaceous could be used as a source by others in the future—it period of Myanmar." The editorial staff was alerted is only the classification of the find that has been to a possible misclassification of the fossil put in doubt. -

Spider Webs and Windows As Potentially Important Sources of Hummingbird Mortality

J. Field Ornithol., 68(1):98--101 SPIDER WEBS AND WINDOWS AS POTENTIAIJJY IMPORTANT SOURCES OF HUMMINGBIRD MORTALITY DEVON L. G•nqAM Departmentof Biology Universityof Miami PO. Box 249118 Coral Gables,Florida, 33124 USA Abstract.--Sourcesof mortality for adult hummingbirdsare varied, but most reports are of starvationand predation by vertebrates.This paper reportstwo potentiallyimportant sources of mortality for tropical hermit hummingbirds,entanglement in spiderwebs and impacts with windows.Three instancesof hermit hummingbirds(Phaethornis spp.) tangled in webs of the spider Nephila clavipesin Costa Rica are reported. The placement of webs of these spidersin sitesfavored by hermit hummingbirdssuggests that entanglementmay occur reg- ularly. Observationsat buildingsalso suggest that traplining hermit hummingbirdsmay be more likely to die from strikingwindows than other hummingbirds.Window kills may need to be consideredfor studiesof populationsof hummingbirdslocated near buildings. TELAS DE ARAI•A Y VENTANAS COMO FUENTES POTENCIALES DE MORTALIDAD PARA ZUMBADORES Sinopsis.--Lasfuentes de mortalidad para zumbadoresson variadas.Pero la mayoria de los informes se circunscribena inanicitn y a depredacitn pot parte de vertebrados.En este trabajo se informan dos importantesfuentes de mortalidad para zumbadorestropicales (Phaethornisspp.) como los impactoscontra ventanasy el enredarsecon tela de arafia. Se informan tres casosde zumbadoresenredados con tela de la arafia Nephila clavipesen Costa Rica. La construccitn de las telas de arafia en lugares -

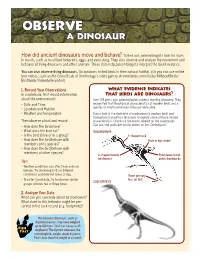

Observebserve a D Dinosaurinosaur

OOBSERVEBSERVE A DDINOSAURINOSAUR How did ancient dinosaurs move and behave? To fi nd out, paleontologists look for clues in fossils, such as fossilized footprints, eggs, and even dung. They also observe and analyze the movement and behavior of living dinosaurs and other animals. These data help paleontologists interpret the fossil evidence. You can also observe living dinosaurs. Go outdoors to fi nd birds in their natural habitat. (Or you can use online bird videos, such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s video gallery at www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/ BirdGuide/VideoGallery.html) 1. Record Your Observations What Evidence IndiCates In a notebook, fi rst record information That Birds Are Dinosaurs? about the environment: Over 125 years ago, paleontologists made a startling discovery. They • Date and Time recognized that the physical characteristics of modern birds and a • Location and Habitat species of small carnivorous dinosaur were alike. • Weather and temperature Take a look at the skeletons of roadrunner (a modern bird) and Coelophysis (an extinct dinosaur) to explore some of these shared Then observe a bird and record: characteristics. Check out the bones labeled on the roadrunner. • How does the bird move? Can you fi nd and label similar bones on the Coelophysis? • What does the bird eat? ROADRUNNER • Is the bird alone or in a group? S-shaped neck • How does the bird behave with Hole in hip socket members of its species? • How does the bird behave with members of other species? V-shaped furcula Pubis bone in hip (wishbone) points backwards Tips: • Weather conditions can affect how animals behave. -

Hummingbird Haven Backyard Habitat for Wildlife

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Hummingbird Haven Backyard Habitat for Wildlife From late March through mid November, if you and then spending their winters in Mexico. look carefully, you may find a small flying Beating their wings 2.7 million times, the jewel in your backyard. The ruby-throated ruby-throated hummingbird flies 500 miles hummingbird may be seen zipping by your nonstop across the Gulf of Mexico during porch or flitting about your flower migration. This trip averages 18-20 hours garden. Inquisitive by nature, these but with a strong tail wind, the flight takes tiny birds will fly close to investigate ten hours. To survive, migrating hummers your colorful blouse or red baseball cap. must store fat and fuel up before and right The hummingbird, like many species of after crossing the Gulf—there are no wildlife is plagued by loss of habitat. sources of nectar over the ocean! However, by providing suitable backyard habitat you can help this flying jewel of a bird. Hummingbird Flowers Flowers Height Color Bloom time Hummingbird Habitat A successful backyard haven for hummingbirds contains a Herbaceous Plants variety of flowering plants including tall and medium trees, Bee Balm 2-4' W, P, R, L summer shrubs, vines, perennial and annual flowers. Flowering plants Blazing Star 2-6' L summer & fall provide hummers with nectar for energy and insects for Cardinal Flower 2-5' R summer protein. Trees and shrubs provide vertical structure for nesting, perching and shelter. No matter what size garden, try Columbine 1-4' all spring & summer to select a variety of plants to ensure flowering from spring Coral Bells 6-12" W, P, R spring through fall. -

Hummingbirds for Kids

Hummingbird Facts & Activity for Kids Hummingbird Facts: Georgia is home to 11 hummingbird species during the year: 1. ruby-throated 2. black-chinned 3. rufous 4. calliope 5. magnificent 6. Allen's 7. Anna's 8. broad-billed 9. green violet-ear 10. green-breasted mango 11. broad-tailed The ruby-throated hummingbird is the only species of hummingbird known to nest to Georgia. These birds weigh around 3 grams-- as little as a first-class letter. The female builds the walnut-sized nest without any help from her mate, a process that can take up to 12 days. The female then lays two eggs, each about the size of a black-eyed pea. In Georgia, female ruby-throated hummers produce up to two broods per year. Nests are typically built on a small branch that is parallel to or dips downward. The birds sometimes rebuild the nest they used the previous year. Keep at least one feeder up throughout the year. You cannot keep hummingbirds from migration by leaving feeders up during the fall and winter seasons. Hummingbirds migrate in response to a decline in day length, not food availability. Most of the rare hummingbirds found in Georgia are seen during the winter. Homemade Hummingbird Feeders: You can use materials from around your home to make a feeder. Here is a list of what you may use: • Small jelly jar • Salt shaker • Wire or coat hanger for hanging • Red pipe cleaners Homemade Hummingbird Food: • You will need--- 1 part sugar to 4 parts water • Boil the water for 2–3 minutes before adding sugar. -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed -

Attracting Hummingbirds

BirdNotes 02 Attracting Hummingbirds ♂ RUBY-THROATED HUMMINGBIRD The tiniest birds in the world are also among the most fascinating and the easiest to watch, sometimes from inches away in your window feeders. Feeding hummingbirds is fun and rewarding and, when done properly, can also make life easier for hummingbirds. Hummingbirds get quick energy from sugar-water feeders, energy that fuels their search for the insects and flowers which provide most of their nourishment. selecting feeders he most important feature of a Tgood hummingbird feeder is that it be easy to open and to clean. If you can’t easily reach every bit of inside surface with a bottle brush, the feed- er will soon foster bacteria, fungi, and other harmful organisms. Feeders should have red parts. Flowers pollinated by hummingbirds are often red, and hummingbirds are attracted to that color. Hamster water bottles and similar items are much more likely to attract hummingbirds if part of the Recipe for success: There’s no need to add red food color to sugar water, or to use red- glass is painted with red nail polish or colored commercial mixes. Flower nectar is clear and red food coloring may be harmful something red is placed on them. to hummingbirds. Some feeders come with bee guards— bird tongues have no trouble, so these Hummingbirds are exceptionally plastic screens that fit over the feed- feeders are often the best choice for territorial and often fight with one ing ports. When these are yellow, they discouraging flying insects. another. You will attract more hum- may actually attract yellow jacket mingbirds that can feed with fewer Some feeders have ant moats. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Hummingbirds

Prepared for the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign (NAPPC) Photo Hugh Vandervoort 6 things you can do for hummingbirds 1. Provide food by planting nectar plants or with careful use of feeder 2. Join a citizen science project • www.hummingbirdsathome.org • www.ebird.org • www.rubythroat.org • www.feederwatch.org 3. Provide a water source Promoting (e.g. fountain, sprinkler, or Hummingbirds How You Can birdbath with a mister) 4. Donate to organizations that Help Them support hummingbird and pollinator conservation Why are hummingbirds 5. Join the Million Pollinator important? Garden Challenge at www. Hummingbirds play an important role in the pollinator.org/million food web, pollinating a variety of fl owering plants, some of which are specifi cally adapted 6. Learn more at www.pollinator. to pollination by hummingbirds. Some tropical org/hummingbirds hummingbirds are at risk, like other pollinators, due to habitat loss and changes in the distribution and abundance of nectar plants. Where are they found? There are more than 300 species of hummingbirds in the world, all of which are found only in the western hemisphere, from southeastern Alaska to southern Chile. Many more species can be found in the tropics than in temperate zones. Many North American hummingbird species are migratory, covering enormous distances each year as they journey between summer breeding grounds and NAPPC overwintering areas. Photo Michael Duncan Photo Jillian Cowles Visit www.pollinator.org/brochures.htm to order copies of this brochure. What do they need? Food Hummingbirds feed by day on nectar As a result, many hummingbird species are from fl owers, including annuals, perennials, incredibly sensitive to environmental change trees, shrubs, and vines. -

Morphology of the Kidney in a Nectarivorous Bird, the Anna's Hummingbird Calypte Anna

J. Zool., Lond. (1998) 244, 175±184 # 1998 The Zoological Society of London Printed in the United Kingdom Morphology of the kidney in a nectarivorous bird, the Anna's hummingbird Calypte anna G. Casotti1*, C. A. Beuchat2 and E. J. Braun3 1 Department of Biology, West Chester University, West Chester, PA, 19383, U.S.A. 2 Department of Biology, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA, 92182, U.S.A. 3 Department of Physiology, Arizona Health Sciences Center, University of Arizona, P.O. Box 245051, Tucson, AZ, 85724±5051, U.S.A. (Accepted 21 April 1997) Abstract The kidneys of Anna's hummingbird (Calypte anna) differ in several signi®cant ways from those of other birds that have been examined. The kidneys of this nectarivore contain very little medullary tissue; 90% of the total volume of the kidneys is cortical tissue, with medulla accounting for only an additional 2%. More than 99% of the nephrons are the so-called `reptilian type', which lack the loop of Henle. The few looped (`mammalian type') nephrons are incorporated into only a few medullary cones per kidney. The loopless nephrons are similar to those of other birds. However, the looped nephrons differ in that they lack the thin descending limb of the loop of Henle, which is found in other birds and is thought to play an important role in the countercurrent multiplier system in the avian kidney. Instead, the cells of the nephron segment following the pars recta of the proximal tubule resemble those of the thick ascending limb, with the large populations of mitochondria that are typical of transporting epithelia and no reduction in cell height. -

Visual Resolution of Anna's Hummingbirds (Calypte Anna) in Space and Time

Visual Resolution of Anna's Hummingbirds (Calypte anna) in Space and Time by Tyee Kenneth Fellows B.Sc., The University of British Columbia, 2013 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Zoology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) June 2015 © Tyee Kenneth Fellows, 2015 Abstract The sampling of spatial and temporal visual information for all living organisms is finite. The speed and accuracy of visual systems contributes in part to an animal's sensitivity to visual motion. The ability to see swift motions is a crucial adaptation among bird species, which are high-speed animals that navigate in a three-dimensional world. Hummingbirds are emerging as important models for studying visual guidance in vertebrates. However, their sensitivity to visual motion remains unknown. A method that can be used to identify hummingbirds' sensitivity to visual motion is to characterise the spatial and temporal acuity of their visual system. It is hypothesised that temporal acuity scales positively with mass-specific metabolic rate and negatively with body size, and spatial acuity scales positively with body size. Given hummingbirds possess the highest mass- specific metabolic rates among vertebrates and the smallest body sizes among birds, I predicted that the Anna's hummingbird (Calypte anna) would have high temporal and low spatial acuities among bird species. Using operant conditioning and optocollic reflex experiments, I identified the temporal and spatial acuity thresholds of the Anna's hummingbird's visual system. Training hummingbirds to differentiate flickering from non-flickering lights at different rates and colours measured their temporal acuity for wavelengths of light between 380-750nm.