Simultaneous Multiple Nests of Calliope Hummingbird and Rufous Hummingbird

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Printable Species Checklist Only (PDF)

Waterfowl N Shorebirds N Gulls and Terns N Owls N Greater Scaup American Avocet Bonaparte’s Gull Barn Owl ◡ Lesser Scaup ◡ Black Oystercatcher Franklin’s Gull Great Horned Owl ◡ Harlequin Duck Black-bellied Plover Heermann’s Gull Snowy Owl Surf Scoter American Golden-Plover Mew Gull Northern Pygmy-Owl White-winged Scoter Pacific Golden-Plover Ring-billed Gull Barred Owl ◡ Black Scoter Semipalmated Plover Western Gull 2 Short-eared Owl Long-tailed Duck Killdeer ◡ California Gull Northern Saw-whet Owl ◡ Bufflehead Whimbrel Herring Gull Kingfishers Common Goldeneye Long-billed Curlew Iceland Gull Belted Kingfisher ◡ Barrow’s Goldeneye Marbled Godwit Glaucous-winged Gull 2 ◡ Woodpeckers Hooded Merganser ◡ Ruddy Turnstone GWxWestern Gull (hybrid) ◡ Red-breasted Sapsucker ◡ Common Merganser Black Turnstone Caspian Tern P Downy Woodpecker ◡ Red-breasted Merganser Red Knot Common Tern Hairy Woodpecker ◡ Ruddy Duck ◡ Surfbird Loons Pileated Woodpecker ◡ Quail and Allies Sharp-tailed Sandpiper Red-throated Loon Northern Flicker ◡ California Quail ◡ Stilt Sandpiper Pacific Loon Falcons Ring-necked Pheasant ◡ Sanderling Common Loon American Kestrel ◡ P Grebes Dunlin Yellow-billed Loon 1 Merlin Peregrine Falcon Pied-billed Grebe ◡ Rock Sandpiper Cormorants Flycatchers Horned Grebe Baird’s Sandpiper Brandt’s Cormorant Olive-sided Flycatcher Red-necked Grebe Least Sandpiper Pelagic Cormorant ◡ Western Wood-Pewee P Eared Grebe Pectoral Sandpiper Double-crested Cormorant ◡ Willow Flycatcher Western Grebe Semipalmated Sandpiper Pelicans ◡ Hammond’s Flycatcher -

Attracting Hummingbirds to Your Garden Using Native Plants

United States Department of Agriculture Attracting Hummingbirds to Your Garden Using Native Plants Black-chinned Hummingbird feeding on mountain larkspur, fireweed, and wild bergamot (clockwise from top) Forest National Publication April Service Headquarters Number FS-1046 2015 Hummingbird garden guide Many of us enjoy the beauty of flowers in our backyard and community gardens. Growing native plants adds important habitat for hummingbirds and other wildlife—especially pollinators. Even small backyard gardens can make a difference. Gardening connects us to nature and helps us better understand how nature works. This guide will help you create a hummingbird- What do hummingbirds, friendly garden. butterflies, and bees have in common? They all pollinate flowering plants. Broad-tailed Hummingbird feeding on scarlet gilia Hummingbirds are Why use native plants in restricted to the Americas with more your garden? than 325 species of Hummingbirds have evolved with hummingbirds in North, Central, and native plants, which are best adapted South America. to local growing seasons, climate, and soil. They prefer large, tubular flowers that are often (but not always) red in color. In this guide, we feature seven hummingbirds that breed in the United States. For each one, we also highlight two native plants found in its breeding range. These native plants are easy to grow, need little water once established, and offer hummingbirds abundant nectar. 2 Hummingbirds and pollination Ruby-throated Hummingbird feeding on the At rest, a hummer’s nectar and pollen heart beats an of blueberry flowers average of 480 beats per minute. On cold nights, it goes into What is pollination? torpor (hibernation- like state), and its Pollination is the process of moving pollen heart rate drops to (male gamete) from one flower to the ovary of another 45 to 180 beats per minute. -

Paper Describing Hummingbird-Sized Dinosaur Retracted 24 July 2020, by Bob Yirka

Paper describing hummingbird-sized dinosaur retracted 24 July 2020, by Bob Yirka teeth. Some in the field were so sure that it was a lizard and not a dinosaur that they wrote and uploaded a paper to the bioRxiv preprint server outlining their concerns. The authors of the paper then published a response addressing their concerns and refuting the skeptics' arguments. That was followed by another team reporting that they had found a similar fossil and after studying it, had deemed it to be a lizard. In reviewing both the paper and the evidence presented by others in the field, the editors at Nature chose to retract the paper. A CT scan of the skull of Oculudentavis by LI Gang, The researchers who published the original paper Oculudentavis means eye-tooth-bird, so named for its appear to be divided on their assessment of the distinctive features. Credit: Lars Schmitz retraction, with some insisting there was no reason for the paper to be retracted and others acknowledging that they had made a mistake when they classified their find as a dinosaur. In either The journal Nature has issued a retraction for a case, all of the researchers agree that the work paper it published March 11th called they did on the fossil was valid and thus the paper "Hummingbird-sized dinosaur from the Cretaceous could be used as a source by others in the future—it period of Myanmar." The editorial staff was alerted is only the classification of the find that has been to a possible misclassification of the fossil put in doubt. -

Spider Webs and Windows As Potentially Important Sources of Hummingbird Mortality

J. Field Ornithol., 68(1):98--101 SPIDER WEBS AND WINDOWS AS POTENTIAIJJY IMPORTANT SOURCES OF HUMMINGBIRD MORTALITY DEVON L. G•nqAM Departmentof Biology Universityof Miami PO. Box 249118 Coral Gables,Florida, 33124 USA Abstract.--Sourcesof mortality for adult hummingbirdsare varied, but most reports are of starvationand predation by vertebrates.This paper reportstwo potentiallyimportant sources of mortality for tropical hermit hummingbirds,entanglement in spiderwebs and impacts with windows.Three instancesof hermit hummingbirds(Phaethornis spp.) tangled in webs of the spider Nephila clavipesin Costa Rica are reported. The placement of webs of these spidersin sitesfavored by hermit hummingbirdssuggests that entanglementmay occur reg- ularly. Observationsat buildingsalso suggest that traplining hermit hummingbirdsmay be more likely to die from strikingwindows than other hummingbirds.Window kills may need to be consideredfor studiesof populationsof hummingbirdslocated near buildings. TELAS DE ARAI•A Y VENTANAS COMO FUENTES POTENCIALES DE MORTALIDAD PARA ZUMBADORES Sinopsis.--Lasfuentes de mortalidad para zumbadoresson variadas.Pero la mayoria de los informes se circunscribena inanicitn y a depredacitn pot parte de vertebrados.En este trabajo se informan dos importantesfuentes de mortalidad para zumbadorestropicales (Phaethornisspp.) como los impactoscontra ventanasy el enredarsecon tela de arafia. Se informan tres casosde zumbadoresenredados con tela de la arafia Nephila clavipesen Costa Rica. La construccitn de las telas de arafia en lugares -

57 HUMMINGBIRDS 1 PLAIN-CAPPED STARTHROAT Heliomaster Constantii 11.5–12.5Cm Field Notes: Often Makes Low Sallies to Capture Flying Insects

Copyrighted Material 57 HUMMINGBIRDS 1 PLAIN-CAPPED STARTHROAT Heliomaster constantii 11.5–12.5cm field notes: Often makes low sallies to capture flying insects. voice: A loud peek; song transcribed as chip chip chip chip pi-chip chip chip..., or chi chi chi chi whit-it chi.... habitat: Shrubby, arid woodland, woodland edge and thickets. distribution: Rare vagrant from Mexico. 2 BAHAMA WOODSTAR Calliphlox evelynae 8–9.5cm field notes: Female has buff tips on outermost tail feathers. Feeds on nectar and by hawked insects. voice: A dry prititidee prititidee prititidee; also a sharp tit titit tit titit, which often speeds into a rattle. habitat: Mixed pine forests, forest edge, clearings, scrub and large gardens. distribution: Very rare vagrant from the Bahamas. 3 LUCIFER HUMMINGBIRD Calothorax lucifer 9–10cm field notes: Male has 3 a forked tail. Feeds on nectar and insects which are obtained by brief fly-catching sallies. voice: Twittering chips. habitat: Desert areas with agave, mountain slopes and canyons. distribution: Summers in SW Texas and S Arizona. 4 RUBY-THROATED HUMMINGBIRD Archilochus colubris 8–9.5cm field notes: Feeds on nectar; insects are taken during fly-catching sallies. voice: 4 A squeaking cric-cric. habitat: Woodland edge, copse and gardens. distribution: Summers in E USA and S Canada, from Alberta eastwards. 5 BLACK-CHINNED HUMMINGBIRD Archilochus alexandri 10cm field notes: Female very similar to Ruby-throated Hummingbird. voice: A husky tiup, tiv or tipip. 5 Song is a weak warble. habitat: Dry scrub. distribution: Summers in W and SW USA. 6 ANNA’S HUMMINGBIRD Calypte anna 10–11cm field notes: Feeds on nectar and insects, which are gleaned or hawked. -

Observebserve a D Dinosaurinosaur

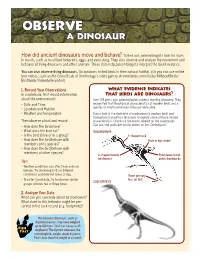

OOBSERVEBSERVE A DDINOSAURINOSAUR How did ancient dinosaurs move and behave? To fi nd out, paleontologists look for clues in fossils, such as fossilized footprints, eggs, and even dung. They also observe and analyze the movement and behavior of living dinosaurs and other animals. These data help paleontologists interpret the fossil evidence. You can also observe living dinosaurs. Go outdoors to fi nd birds in their natural habitat. (Or you can use online bird videos, such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s video gallery at www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/ BirdGuide/VideoGallery.html) 1. Record Your Observations What Evidence IndiCates In a notebook, fi rst record information That Birds Are Dinosaurs? about the environment: Over 125 years ago, paleontologists made a startling discovery. They • Date and Time recognized that the physical characteristics of modern birds and a • Location and Habitat species of small carnivorous dinosaur were alike. • Weather and temperature Take a look at the skeletons of roadrunner (a modern bird) and Coelophysis (an extinct dinosaur) to explore some of these shared Then observe a bird and record: characteristics. Check out the bones labeled on the roadrunner. • How does the bird move? Can you fi nd and label similar bones on the Coelophysis? • What does the bird eat? ROADRUNNER • Is the bird alone or in a group? S-shaped neck • How does the bird behave with Hole in hip socket members of its species? • How does the bird behave with members of other species? V-shaped furcula Pubis bone in hip (wishbone) points backwards Tips: • Weather conditions can affect how animals behave. -

Poster-Native Plants for Hummingbirds

Think tall. Hummingbirds nest on Planning your garden – the branches of tall shrubs and trees, which provide cover and escape from predators. think like a hummingbird. Think safe harbor. Think diverse. Plant a diversity Domestic cats can kill Think perches. Hummingbirds of flowering species with abundant hummingbirds. Please pollen and nectar. Think native. Hummers are spend much of their time perched on keep them indoors. best adapted to local, native dead branches and dead tree tops— plants, which often need less resting or surveying their territory. Think chemical free. water than ornamentals. Pesticides and insecticides Think showy. Flowers kill insect pollinators and can should bloom in your Think patience. It takes time for native harm hummingbirds. garden throughout the plants to grow and for hummers to find your growing season. Plant garden, especially if you live far from wild willow, currant, and lands. columbine for spring, and aster, salvia, and Think bountiful. Plant big goldenrod for fall patches of each plant species flowers. for better foraging efficiency. Think aware. Observe hummingbirds when you walk outside in nature. Notice which flowers attract them. Think friendly. Create hummingbird-friendly gardens both at home, at schools and in public parks. Help people learn more about hummingbirds and native plants. Calliope Hummingbird feeding on scarlet paintbrush Think a little messy. Most insects nest underground or in leafy debris so avoid using weed cloth or heavy mulch. More insects mean more food for hummingbirds. Think water. Hummingbirds U.S. Forest Service will bathe in dripping water, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W. shallow creeks and even garden Washington, DC 20250 sprinklers. -

Hummingbird Haven Backyard Habitat for Wildlife

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Hummingbird Haven Backyard Habitat for Wildlife From late March through mid November, if you and then spending their winters in Mexico. look carefully, you may find a small flying Beating their wings 2.7 million times, the jewel in your backyard. The ruby-throated ruby-throated hummingbird flies 500 miles hummingbird may be seen zipping by your nonstop across the Gulf of Mexico during porch or flitting about your flower migration. This trip averages 18-20 hours garden. Inquisitive by nature, these but with a strong tail wind, the flight takes tiny birds will fly close to investigate ten hours. To survive, migrating hummers your colorful blouse or red baseball cap. must store fat and fuel up before and right The hummingbird, like many species of after crossing the Gulf—there are no wildlife is plagued by loss of habitat. sources of nectar over the ocean! However, by providing suitable backyard habitat you can help this flying jewel of a bird. Hummingbird Flowers Flowers Height Color Bloom time Hummingbird Habitat A successful backyard haven for hummingbirds contains a Herbaceous Plants variety of flowering plants including tall and medium trees, Bee Balm 2-4' W, P, R, L summer shrubs, vines, perennial and annual flowers. Flowering plants Blazing Star 2-6' L summer & fall provide hummers with nectar for energy and insects for Cardinal Flower 2-5' R summer protein. Trees and shrubs provide vertical structure for nesting, perching and shelter. No matter what size garden, try Columbine 1-4' all spring & summer to select a variety of plants to ensure flowering from spring Coral Bells 6-12" W, P, R spring through fall. -

Hummingbirds for Kids

Hummingbird Facts & Activity for Kids Hummingbird Facts: Georgia is home to 11 hummingbird species during the year: 1. ruby-throated 2. black-chinned 3. rufous 4. calliope 5. magnificent 6. Allen's 7. Anna's 8. broad-billed 9. green violet-ear 10. green-breasted mango 11. broad-tailed The ruby-throated hummingbird is the only species of hummingbird known to nest to Georgia. These birds weigh around 3 grams-- as little as a first-class letter. The female builds the walnut-sized nest without any help from her mate, a process that can take up to 12 days. The female then lays two eggs, each about the size of a black-eyed pea. In Georgia, female ruby-throated hummers produce up to two broods per year. Nests are typically built on a small branch that is parallel to or dips downward. The birds sometimes rebuild the nest they used the previous year. Keep at least one feeder up throughout the year. You cannot keep hummingbirds from migration by leaving feeders up during the fall and winter seasons. Hummingbirds migrate in response to a decline in day length, not food availability. Most of the rare hummingbirds found in Georgia are seen during the winter. Homemade Hummingbird Feeders: You can use materials from around your home to make a feeder. Here is a list of what you may use: • Small jelly jar • Salt shaker • Wire or coat hanger for hanging • Red pipe cleaners Homemade Hummingbird Food: • You will need--- 1 part sugar to 4 parts water • Boil the water for 2–3 minutes before adding sugar. -

Maintaining and Improving Habitat for Hummingbirds in Colorado, Wyoming and South Dakota

United States Department of Agriculture Maintaining and Improving Habitat for Hummingbirds in Colorado, Wyoming and South Dakota A Land Manager’s Guide Forest Service National Headquarters Introduction Food Hummingbirds play an important role in the food web, Hummingbirds feed by day on nectar pollinating a variety of owering plants, some of which from owers, including annuals, perenni- are speci cally adapted to pollination by hummingbirds. als, trees, shrubs, and vines. Native nectar Some hummingbirds are at risk, like other pollinators, plants are listed in the table near the end due to habitat loss, changes in the distribution and of this guide. ey feed while hovering or, abundance of nectar plants (which are a ected by climate if possible, while perched. ey also eat change), the spread of invasive plants, and pesticide use. Rufous Hummingbird nest insects, such as fruit- ies and gnats, and is guide is intended to help you provide and improve Courtesy of Martin Hutten will consume tree sap, when it is available. habitat for hummingbirds, as well as other pollinators, ey obtain tree sap from sap wells drilled in Colorado, Wyoming, and South Dakota. While hummingbirds, like all birds, have the in trees by sapsuckers and other hole-drill- Western columbine—Aquilegia formosa Courtesy of Gary A. Monroe basic habitat needs of food, water, shelter, and space, this guide is focused on providing ing birds. USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database food—the plants that provide nectar for hummingbirds. Because climate, geology, and vegetation vary widely in di erent areas, speci c recommendations are presented for each ecoregion in Colorado, Wyoming, and South Dakota. -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed -

Notes on the Location and Construction of the Nest of the Calliope Hummingbird with Three Illustrations

Jan.,1927 19 NOTES ON THE LOCATION AND CONSTRUCTION OF THE NEST OF THE CALLIOPE HUMMINGBIRD WITH THREE ILLUSTRATIONS By WINTON WEYDEMEYER SSUMING that the nesting habits of the Calliope Hummingbird throughout A the northwesternmost county of Montana, where it is a common breeder, may largely be typical of the species, I give here information obtained in studying this bird in that locality and in examining a few more than twenty nests. In Lincoln County the Calliope Hummingbird (Stellula calliope) nests along streams throughout most of the Canadian zone and downward into the upper borders of the Transition zone. During the nesting season and late summer it also frequents open mountains, ranging into the Hudsonian zone, and during May and August is commonly seen in the breeding areas of lower Transition zone species. Tree associ- ations evidently have greater influence on its range than does elevation. In the east- ern part of the county I have found the species to be common during the nesting season at 7000 feet, although I have never chanced actually to see a nest above 4800 feet. In the Kootenai Valley, near Libby, I have found it nesting abundantly at an elevation Fig. 10. TRANSITION ZONE TYPE OF HABITAT OF THE CALLIOPE HUMMINGBIRD, ALONG THE K~~TENAI RIVER NEAR LIBBY, MONTANA, AT AN ELEVATION OF 2160 FEET. of less than 2100 feet, and I have no doubt that it breeds below 1900 feet a few miles distant, in the lower end of the valley, the only place in Montana where so low an elevation occurs.