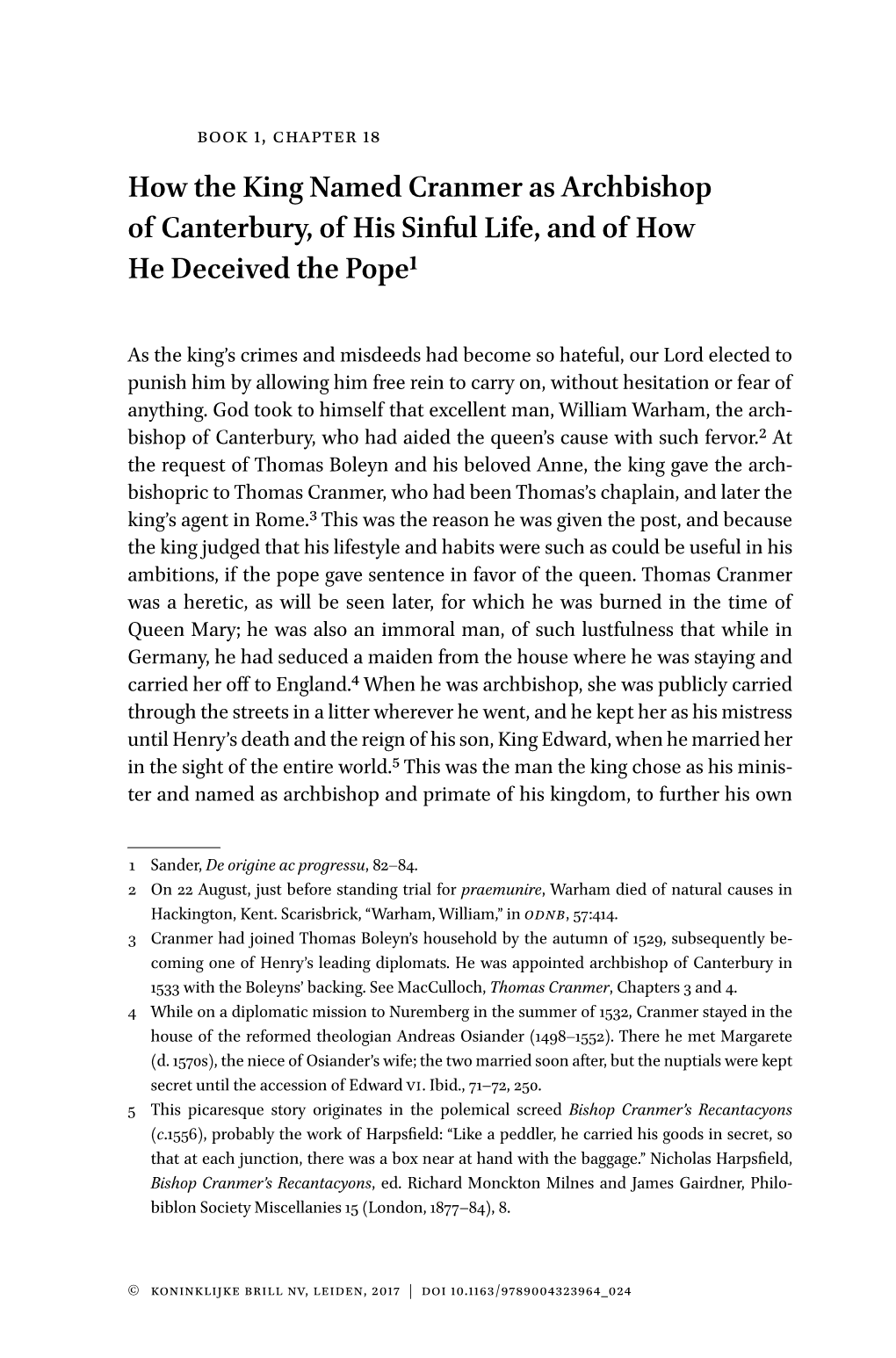

How the King Named Cranmer As Archbishop of Canterbury, of His Sinful Life, and of How He Deceived the Pope1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

Magis ... Pro Nostra Sentencia

"Magis ... Pro Nostra Sentencia": John Wyclif, his mediaeval Predecessors and reformed Successors, and a pseudo-Augustinian Eucharistic Decretal Augustiniana [Institutum Historicum Augustianum Lovanii], 45, fasc. 3-4 (1995), 213-245. John Wyclif had not a high regard for Lanfranc. There were general grounds: though he lived three hundred years earlier, Lanfranc was on the wrong side of the great millennial divide. For the first one thousand years after the ascension of Christ, Satan, the father of lies had been bound, as the Apocalypse says. Consequently, in that time, there had been a succession of truthful teachers, "correctly logical, philosophers conformed to the faith of Scripture".1 Ambrose, Augustine and Jerome were the principal of these, and "any of them is one thousand times more valuable than a dozen subsequent doctors and popes, when the enemy of truth is free and sowing lies contrary to the school of Christ".2 There were, moreover, particular grounds which moved Wyclif to go far beyond despising Lanfranc's authority. He both made him an object of invective, and also directed reason, as well as, scriptural and patristic authority against him. There was the manner of Lanfranc's attack on Berengarius, to whom Wyclif had a most ambiguous relation. He was strongly enthusiastic for the decretal "Ego Berengarius" which recorded the confession of Berengar. But this was, after all, an enforced retraction!3 They were, in Wyclif's view, fellow soldiers in the army of truth. Like the Berengar of the decretal, Wyclif held both that the sacrament of the altar was truly, even, "substantially", the body of Christ, and also that the identity of the sacrament and Christ's body was figurative. -

Worldwide Communion: Episcopal and Anglican Lesson # 23 of 27

Worldwide Communion: Episcopal and Anglican Lesson # 23 of 27 Scripture/Memory Verse [Be] eager to maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace: There is one body and one Spirit just as you were called to the one hope that belongs to your call; one Lord, one Faith, one baptism, one God and Father of us all. Ephesians 4: 3 – 6 Lesson Goals & Objectives Goal: The students will gain an understanding and appreciation for the fact that we belong to a church that is larger than our own parish: we are part of The Episcopal Church (in America) which is also part of the worldwide Anglican Communion. Objectives: The students will become familiar with the meanings of the terms, Episcopal, Anglican, Communion (as referring to the larger church), ethos, standing committee, presiding bishop and general convention. The students will understand the meaning of the “Four Instruments of Unity:” The Archbishop of Canterbury; the Meeting of Primates; the Lambeth Conference of Bishops; and, the Anglican Consultative Council. The students will encounter the various levels of structure and governance in which we live as Episcopalians and Anglicans. The students will learn of and appreciate an outline of our history in the context of Anglicanism. The students will see themselves as part of a worldwide communion of fellowship and mission as Christians together with others from throughout the globe. The students will read and discuss the “Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral” (BCP pages 876 – 877) in order to appreciate the essentials of an Anglican identity. Introduction & Teacher Background This lesson can be as exciting to the students as you are willing to make it. -

Kent Archæological Society Library

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society KENT ARCILEOLOGICAL SOCIETY LIBRARY SIXTH INSTALMENT HUSSEY MS. NOTES THE MS. notes made by Arthur Hussey were given to the Society after his death in 1941. An index exists in the library, almost certainly made by the late B. W. Swithinbank. This is printed as it stands. The number given is that of the bundle or box. D.B.K. F = Family. Acol, see Woodchurch-in-Thanet. Benenden, 12; see also Petham. Ady F, see Eddye. Bethersden, 2; see also Charing Deanery. Alcock F, 11. Betteshanger, 1; see also Kent: Non- Aldington near Lympne, 1. jurors. Aldington near Thurnham, 10. Biddend.en, 10; see also Charing Allcham, 1. Deanery. Appledore, 6; see also Kent: Hermitages. Bigge F, 17. Apulderfield in Cudham, 8. Bigod F, 11. Apulderfield F, 4; see also Whitfield and Bilsington, 7; see also Belgar. Cudham. Birchington, 7; see also Kent: Chantries Ash-next-Fawkham, see Kent: Holy and Woodchurch-in-Thanet. Wells. Bishopsbourne, 2. Ash-next-Sandwich, 7. Blackmanstone, 9. Ashford, 9. Bobbing, 11. at Lese F, 12. Bockingfold, see Brenchley. Aucher F, 4; see also Mottinden. Boleyn F, see Hever. Austen F (Austyn, Astyn), 13; see also Bonnington, 3; see also Goodneston- St. Peter's in Tha,net. next-Wingham and Kent: Chantries. Axon F, 13. Bonner F (Bonnar), 10. Aylesford, 11. Boorman F, 13. Borden, 11. BacIlesmere F, 7; see also Chartham. Boreman F, see Boorman. Baclmangore, see Apulderfield F. Boughton Aluph, see Soalcham. Ballard F, see Chartham. -

KENT. Canterbt'ry, 135

'DIRECTORY.] KENT. CANTERBt'RY, 135 I FIRE BRIGADES. Thornton M.R.O.S.Eng. medical officer; E. W. Bald... win, clerk & storekeeper; William Kitchen, chief wardr City; head quarters, Police station, Westgate; four lad Inland Revilnue Offices, 28 High street; John lJuncan, ders with ropes, 1,000 feet of hose; 2 hose carts & ] collector; Henry J. E. Uarcia, surveyor; Arthur Robert; escape; Supt. John W. Farmery, chief of the amal gamated brigades, captain; number of men, q. Palmer, principal clerk; Stanley Groom, Robert L. W. Cooper & Charles Herbert Belbin, clerk.s; supervisors' County (formed in 1867); head quarters, 35 St. George'l; street; fire station, Rose lane; Oapt. W. G. Pidduck, office, 3a, Stour stroot; Prederick Charles Alexander, supervisor; James Higgins, officer 2 lieutenants, an engineer & 7 men. The engine is a Kent &; Canterbury Institute for Trained Nur,ses, 62 Bur Merryweather "Paxton 11 manual, & was, with all tht' gate street, W. H. Horsley esq. hon. sec.; Miss C.!". necessary appliances, supplied to th9 brigade by th, Shaw, lady superintendent directors of the County Fire Office Kent & Canterbury Hospital, Longport street, H. .A.. Kent; head quarters, 29 Westgate; engine house, Palace Gogarty M.D. physician; James Reid F.R.C.S.Eng. street, Acting Capt. Leonard Ashenden, 2 lieutenant~ T. & Frank Wacher M.R.C.S.Eng. cOJ1J8ulting surgeons; &; 6 men; appliances, I steam engine, I manual, 2 hQ5l Thomas Whitehead Reid M.RC.S.Eng. John Greasley Teel!! & 2,500 feet of hose M.RC.S.Eng. Sidney Wacher F.R.C.S.Eng. & Z. Fren Fire Escape; the City fire escape is kept at the police tice M.R.C.S. -

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Abbreviations Used ....................................................................................................... 4 3 Archbishops of Canterbury 1052- .................................................................................. 5 Stigand (1052-70) .............................................................................................................. 5 Lanfranc (1070-89) ............................................................................................................ 5 Anselm (1093-1109) .......................................................................................................... 5 Ralph d’Escures (1114-22) ................................................................................................ 5 William de Corbeil (1123-36) ............................................................................................. 5 Theobold of Bec (1139-61) ................................................................................................ 5 Thomas Becket (1162-70) ................................................................................................. 6 Richard of Dover (1174-84) ............................................................................................... 6 Baldwin (1184-90) ............................................................................................................ -

Chertsey Abbey : an Existence of the Past

iii^li.iin H.xik i ... l.t.l loolcsdlen and K.M kliin.l : .. Vil-rTii Str.-t. NOTTINGHAM. |. t . tft <6;ri0fence of Photo, by F. A. Monk. [Frontispiece. TRIPTYCH OF TILES FROM CHERTSEY ABBEY, THIRTEENTH CENTURY. of BY LUCY WHEELER. With. Preface by SIR SWINFEN EADY. ARMS OF THE MONASTERY OF S. PETER, ABBEY CHURCH, CHERTSEY. Bonbon : WELLS GARDNER, DARTON & CO., LTD., 3, Paternoster Buildings, E.C., and 44, Victoria Street, S. W. PREFACE THE History of Chertsey Abbey is of more than local interest. Its foundation carries us back to so remote a period that the date is uncertain. The exact date fixed in the is A.D. but Chertsey register 666 ; Reyner, from Capgrave's Life of S. Erkenwald, will have this Abbey to have been founded as early as A.D. 630. That Erken- wald, however, was the real founder, and before he became Bishop of London, admits of no doubt. Even the time of Erkenwald's death is not certain, some placing it in 685, while Stow says he died in 697. His splendid foundation lasted for some nine centuries, and in the following pages will be found a full history of the Abbey and its rulers and possessions until its dissolution by Henry VIII. is incessant is con- Change everywhere, and ; nothing stant or in a or less stable, except greater degree ; the Abbeys which in their time played so important a part in the history and development of the country, and as v houses of learning, have all passed away, but a study of the history of an important Abbey enables us to appre- ciate the part which these institutions played in the past, and some of the good they achieved, although they were not wholly free from abuses. -

The Apostolic Succession of the Right Rev. James Michael St. George

The Apostolic Succession of The Right Rev. James Michael St. George © Copyright 2014-2015, The International Old Catholic Churches, Inc. 1 Table of Contents Certificates ....................................................................................................................................................4 ......................................................................................................................................................................5 Photos ...........................................................................................................................................................6 Lines of Succession........................................................................................................................................7 Succession from the Chaldean Catholic Church .......................................................................................7 Succession from the Syrian-Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch..............................................................10 The Coptic Orthodox Succession ............................................................................................................16 Succession from the Russian Orthodox Church......................................................................................20 Succession from the Melkite-Greek Patriarchate of Antioch and all East..............................................27 Duarte Costa Succession – Roman Catholic Succession .........................................................................34 -

Iburtraits Qrtbhisbups Nt

iB urtraits of the ’ Qrtbhisbups nt fian tzrhury E M . B N Emm i) B Y G . V A A N D I SSU ED W I TH TH E AP P ROV AL O F Hrs G RAC E TH E A R CHB I SHOP OF CAN TER B U RY A . R . M LTD . OWB RAY CO . ON DON : G a t Ca s tl Ox f Ci c s W . L 34 re e Street , ord r u , ’ OXFO R D : 1 06 S . Alda t e s St re e t 1 908 LAM B ETH A LA P C E . E . , S , M a r h c 7 0 . , 9 8 MY DEAR M I SS B EV AN , I cordially approve of y o u r plan of publishing a series of such portraits as exist of the successive occupants of the See of Canterbury . I gather that you propose to a c c omp a ny the plates with such biographical notes as may present the facts in outline to those who have little knowledge of English Church History . I need hardly say that so far as Lambeth is c o n cerned we offer you every facility for the reproduction of pictures or seals . Such a book as you contemplate will have a peculiar f s interest this year, when the See of Canterbury orm the - pivot of a world wide gathering . a m I , Y s our very truly, Si n e d RAN DAL R ( g ) L CAN TUA . -

St Stephen's Church, Hackington and Its

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society ( 253 ) ST. STEPHEN'S CHURCH, HACKINGTON, AND ITS POSSIBLE CONNECTION WITH ARCHBISHOP BALDWIN. BY SURGEON-CAPTAIN KENNETH H. JONES, M.B., R.N. THE first church we know of at Hackmgton was in part built by Archbishop Anselm about 1100 or a httle later, and of this considerable portions stUl remain at the west end and in the nave of the present building. The present church consists of a nave, with a tower at its western end, a chancel, north and south transepts and a south porch. The tower was raised, probably, by Archdeacon Simon Langton, about 1230, upon the walls of Anselm's Norman nave. In order that the Norman nave should be able to carry the weight of the tower, two large buttresses were placed at its north-west and south-west angles, while a very thick wall, some twelve feet high and pierced by a pointed arch, was built from side to side of the nave, inside, to support its eastern wall. AU this is clearly shown on Canon Livett's excellent plan facing page 268. The great buttresses form straight joints below the level of the Norman eaves, and above are shghtly bonded into the tower walls. The windows of the tower, probably of thirteenth century date, were altered in the fifteenth century, when trefoil hoods were added. The whole is surmounted by an octagonal wooden spire dating from the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century. -

Archbishop of Canterbury, and One of the Things This Meant Was That Fruit Orchards Would Be Established for the Monasteries

THE ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY And yet — in fact you need only draw a single thread at any point you choose out of the fabric of life and the run will make a pathway across the whole, and down that wider pathway each of the other threads will become successively visible, one by one. — Heimito von Doderer, DIE DÂIMONEN “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Archbishops of Canterb HDT WHAT? INDEX ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY 597 CE Christianity was established among the Anglo-Saxons in Kent by Augustine (this Roman import to England was of course not the Aurelius Augustinus of Hippo in Africa who had been in the ground already for some seven generations — and therefore he is referred to sometimes as “St. Augustine the Less”), who in this year became the 1st Archbishop of Canterbury, and one of the things this meant was that fruit orchards would be established for the monasteries. Despite repeated Viking attacks many of these survived. The monastery at Ely (Cambridgeshire) would be particularly famous for its orchards and vineyards. DO I HAVE YOUR ATTENTION? GOOD. Archbishops of Canterbury “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY 604 CE May 26, 604: Augustine died (this Roman import to England was of course not the Aurelius Augustinus of Hippo in Africa who had been in the ground already for some seven generations — and therefore he is referred to sometimes as “St. Augustine the Less”), and Laurentius succeeded him as Archbishop of Canterbury. -

Press Release the Archbishop of Canterbury Most Rev Justin Welby

Press Release The Archbishop of Canterbury Most Rev Justin Welby to Visit South India at the invitation of the Church of South India The Archbishop of Canterbury, head of the Anglican Communion, the Most Reverend Justin Welby will be visiting the Church of South India from 31st August to 5th September 2019 along with his spouse Mrs. Caroline Welby, on the invitation of the Moderator of Church of South India, Most Rev. Thomas K. Oommen. The Archbishop of Canterbury will visit the states of Kerala, Karnataka and Telangana. He will be hosted in Kerala by the Madhya Kerala Diocese, in Karnataka by the Karnataka Central Diocese and in Telugu region by the Medak Diocese. The Church of South India is a United and Uniting Church representing the Indian cultural and national ethos formed soon after Indian independence on 27th September 1947. The Anglican, Methodist, Congregational and Presbyterian Churches came together in an organic unity in CSI. As a United and Uniting Church, CSI has membership in three World Communions, namely, the Anglican Communion, the World Communion of Reformed Churches, the World Methodist Council as well as in the World Forum of United and Uniting Churches. The Archbishop of Canterbury is visiting the Church of South India as head of one of the Communions to which CSI belongs. The Most Reverend Justin Welby was installed as the 105th Archbishop of Canterbury on 21st March 2013 at Canterbury Cathedral. In 2017, Archbishop Welby was invited to join the UN Secretary- General António Guterres’ High-Level Advisory Board on Mediation – the only faith leader to be on the panel.