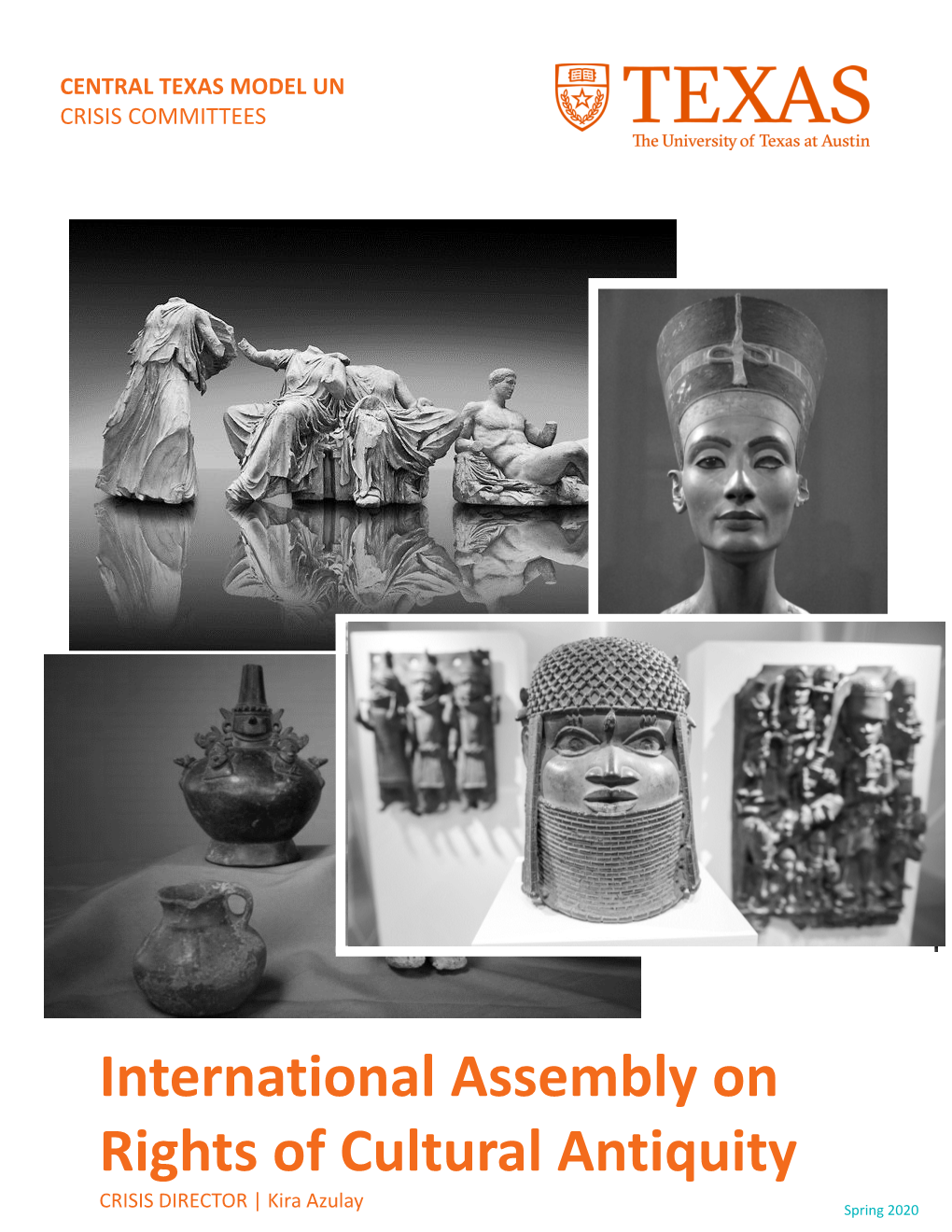

International Assembly on Rights of Cultural Antiquity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Amir Sheikh Nawaf Sworn in As Sheikh Sabah Laid to Rest

SAFAR 14, 1442 AH THURSDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2020 20 Pages Max 38º 150 Fils Min 24º ISSUE NO: 18245 www.kuwaittimes.net New Amir Sheikh Nawaf sworn in as Sheikh Sabah laid to rest Amir urges unity against ‘acute circumstances, critical challenges’ KUWAIT: HH the Amir Sheikh Nawaf Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah takes oath at the National Assembly yesterday. - Photo by Yasser Al-Zayyat By B Izzak The body of Sheikh Sabah, who passed away in a metal coffin. The motorcade then drove to and wore masks in line with coronavirus precautions. hospital in the United States on Tuesday, arrived in Sulaibikhat cemetery, where the late Amir was laid to Assembly Speaker Marzouq Al-Ghanem praised KUWAIT: HH Sheikh Nawaf Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber the country yesterday aboard a Kuwait Airways air- rest in a simple ceremony attended only by close rel- the great achievements of the late Sheikh Sabah Al-Sabah yesterday took the constitutional oath in craft to a reception led by HH the Amir, senior ruling atives because of the coronavirus pandemic. through his wise policies and strategic decisions, the National Assembly to exercise his authority as family members and government dignitaries. The After taking the oath, HH the Amir Sheikh Nawaf which safeguarded the country against dangers. the 16th Amir of the country, as late Amir Sheikh plane was met by royal guard members, each carry- paid tribute to Sheikh Sabah and recalled his major World leaders and Kuwaitis alike have hailed the Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah was laid to rest ing a flagpole at half-staff. -

FOR the PHOENIX to FIND ITS FORM in US. on Restitution, Rehabilitation, and Reparation

FOR THE PHOENIX TO FIND ITS FORM IN US. On Restitution, Rehabilitation, and Reparation INVOCATIONS 20.08.-22.08.2021 WITH Pio Abad Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme Khyam Allami with Julie Normal & Julia Tieke Noah Angell Arjun Appadurai Archive Oumar Atakosso Daniel Romuald Bitouh Benji Boyadgian Hamze Bytyçi Nora Chipaumire Mwazulu Diyabanza Manuela García Aldana Samia Henni Harmony Holiday Simon Inou Gladys Kalichini Yuko Kaseki Chao Tayiana Maina Musa Michelle Mattiuzzi Mnyaka Sururu Mboro Wayne Modest Molemo Moiloa Trixie Munyama Marian Pastor Roces Zaratiana Randrianantenaina Michael Rakowitz Nora Razian Damien Rwegera Avni Sethi Linda-Philomène Tsoungui Die Jugendgruppe WIR SIND HIER! TEAM ARTISTIC DIRECTION Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung CURATORS Elena Agudio Arlette-Louise Ndakoze CURATORIAL ASSISTANCE Kelly Krugman Lili Somogyi PRODUCTION Billy Fowo Sagal Farah Meghna Singh TECHNICAL SUPPORT Mudassir Sheikh Spencer MacDonald SUPPORT Danielle Fogang Sebudandi Karen Heinze Rafal Lazar MANAGEMENT Lynhan Balatbat-Helbock Lema Sikod COMMUNICATIONS Anna Jäger INTERN Lia Milanesio STREAMING Ranav Adhikari Turi Agostino LIGHT DESIGN Gretchen Blegen FUNDING The project is funded by the Kulturstiftung des Bundes (German Federal Cultural Foundation), Art Jameel and ifa Gallery Berlin. The installation “The invisible enemy should not exist” by Michael Rakowitz is made possible by courtesy of Galerie Barbara Wien. SAVVY Contemporary The Laboratory of Form-Ideas INTRO Weaving together words, notes, bodily expressions, and Considering reparations not as a financial debt only, moving images, we contemplate the ways in which the this programme grapples with the work and the Phoenix Finds Its Form In Us, speculating collectively: labour of activists, scholars, poets, and artists that pondering the legal, socio-cultural, financial, and address reparations as a means of finding “new ways political entanglements of restitution. -

TCC Isabella Nikel.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA CENTRO SOCIOECONÔMICO DEPARTAMENTO DE CIÊNCIAS ECONÔMICAS E RELAÇÕES INTERNACIONAIS GRADUAÇÃO EM RELAÇÕES INTERNACIONAIS ISABELLA PEREIRA NIKEL EU PEÇO PELA MEMÓRIA DE ÁFRICA: A cultura do imperialismo no museu moderno “universal” a partir do estudo da expropriação cultural e do memoricídio no Reino de Benin FLORIANÓPOLIS 2021 2 ISABELLA PEREIRA NIKEL EU PEÇO PELA MEMÓRIA DE ÁFRICA: A cultura do imperialismo no museu moderno “universal” a partir do estudo da expropriação cultural e do memoricídio no Reino de Benin Monografia submetida ao curso de Relações Internacionais da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, como requisito obrigatório para a obtenção do grau de Bacharelado. Orientadora: Profª Drª Karine de Souza Silva Florianópolis 2021 3 Ficha de identificação da obra elaborada pelo autor, através do Programa de Geração Automática da Biblioteca Universitária da UFSC. Nikel, Isabella Pereira EU PEÇO PELA MEMÓRIA DE ÁFRICA: A cultura do imperialismo no museu moderno “universal” a partir do estudo da expropriação cultural e do memoricídio no Reino de Benin / Isabella Pereira Nikel ; orientador, Karine de Souza Silva, 2021. 112 p. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso (graduação) -Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Centro Sócio Econômico, Graduação em Relações Internacionais,Florianópolis, 2021. Inclui referências. 1. Relações Internacionais. 2. Expropriação cultural. 3.Memoricídio. 4. Bronzes de Benin. 5. Museu Moderno. I. deSouza Silva, Karine . II. Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Graduação -

Asante Artifacts at the American Museum of Natural History

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects CUNY Graduate Center 6-2021 Challenges of Repatriation: Asante Artifacts at the American Museum of Natural History Abdul-Alim Farook The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/4424 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Challenges of Repatriation: Asante artifact in American Museum of Natural History by ABDUL-ALIM FAROOK A master’s capstone Project submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2021 ii © 2021 ABDUL-ALIM FAROOK All Rights Reserved iii Challenges of Repatriation: Asante artifact in American Museum of Natural History by Abdul-Alim Farook This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the capstone project requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Date Matthew Reilly Capstone Project Advisor Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv ABSTRACT Challenges of Repatriation: Ashanti artifact in American Museum of Natural History by Abdul-Alim Farook Advisor: Matthew Reilly Inspired by calls for the repatriation of famous artifacts like the Benin Bronzes and the Elgin Marbles, for this capstone project, I have analyzed and catalogued 250 sampled Asante artifacts at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH). -

October 2020, Going Through

PAN AFRICAN VISIONS MARKETING AFRICAN SUCCESS STORIES & MORE MAG 1020 Vol III, OCT. 2020. www.panafricanvisions.com Brazil-Africa Mozambique: Cameroon: Forum 2020 In Presidents At “war” Catholic Bishops Sound Côte d›Ivoire: The Ghosts Of The Past Focus Alarm Bells PAN-AFRICAN PRO-AFRICAN www.centurionlg.com Contents PAN AFRICAN VISIONs CONTENTS The Burden of Leadership At 60: As Nigeria Goes, _________ 2 AfCFTA - Former Liberian Minister B. Elias Shoniyin ______ 27 so does Africa __________________________________ 2 French Court Faces a 'Stolen' African Artwork Dilemma ____ 31 Nigeria At 60: A Birthday That Could _________________ 3 On Bakassi Cameroon Denies Owing Any Financial Compensation to Nigeria _____________________________________ 33 Have Been Better _______________________________ 3 Rwanda: Will UN, other International Bodies rescue Paul Rusesa- Ramaphosa Calls on World Leaders to do more in tackling Chal- bagina from terrorism charges? ______________________ 34 lenges Facing Ordinary People ______________________ 6 Sustained Efforts Needed To Boast Brazil-Africa Relations -Prof Mozambique :Former and Current President At "war". ______ 9 Joao Monte ___________________________________ 35 Malawi: President Chakwera Faces Litmus Political Test In Ap- Health Expert Praises Africa's Fight Against Coronavirus ____ 39 pointments ___________________________________ 11 Aid for Sex Rampant in Uganda: UN Report _____________ 40 D.R.Congo: Growing Calls To Expel Rwandan Ambassador __ 13 60 Years After Independence Nigeria's Energy Industry -

Economics Briefs: Rethinking the Basics

Lebanon after the blast The trouble with Trumpian TikTok How much to spend on a vaccine? Economics briefs: rethinking the basics AUGUST 8TH–14TH 2020 The absent student How covid-19 will change college COLLECTION Fifty Fathoms RAISE AWARENESS, TRANSMIT OUR PASSION, HELP PROTECT THE OCEAN BEIJING · CANNES · DUBAI · GENEVA · HONG KONG · KUALA LUMPUR · LAS VEGAS · LONDON · MACAU · MADRID ©Photograph: Laurent Ballesta/Gombessa Project ©Photograph: Laurent www.blancpain-ocean-commitment.com MANAMA · MOSCOW · MUNICH · NEW YORK · PARIS · SEOUL · SHANGHAI · SINGAPORE · TAIPEI · TOKYO · ZURICH Contents The Economist August 8th 2020 3 The world this week Asia 5 A summary of political 17 Sectarianism in India and business news 18 Australia’s internal borders Leaders 19 Corruption in Uzbekistan 7 Universities 19 Schools v hair in Thailand The absent student 20 Banyan Lee Teng-hui, 8 Tech wars Taiwan’s Trojan horse Trumpian TikTok 8 Lebanon China No way to run a country 21 Hunan’s cultural rise 9 Vaccine economics 22 Debate about divorce A bigger dose On the cover 10 Gay rights The world comes out Covid-19 will be painful for 11 Economics universities, but it will also When the facts change bring long-needed change: leader, page 7. Higher United States Letters education was already in 23 Electing a president trouble. The pandemic could 12 On reopening schools, 24 The postal service push some institutions over oil, French accents, the brink: briefing, page 14 Amazon, sports teams 25 Hyperloops 25 Covid-19 and pro sports • Lebanon after the blast Briefing A massive explosion caused by 26 Washington history spectacular negligence shatters 14 Covid-19 and college 27 UBI and cities Uncanny University an already-reeling Lebanese 28 Lexington One America capital, page 33. -

The Continent With

African journalism. October 24 2020 ISSUE NO. 26 The Continent with Inside the illicit trade in West Africa’s oldest artworks (Photo: Lutz Mükke) The Continent ISSUE 26. October 24 2020 Page 2 THE ART THIEVES EDITION This week’s cover story reads like Inside: an action thriller. We travel from Abuja to Paris, from the Nok Valley Nigeria: The state strikes back to New Haven, on the trail of the – with live ammunition (p8, p10) underground dealers who are – Mozambique: The miracle baby quite literally – selling off Nigeria’s born on a boat (p11) history (p14). Then we meet the The virtual world of Fortnite Congolese man on a mission to systematically disadvantages reclaim stolen African artworks Africans (p26) from European museums – even if Kenya, coffee and organised he has to steal them back (p22). crime (p29) The unholy trinity: The self-proclaimed prophet Shepherd Bushiri appeared in court in the South African capital Pretoria on Friday, along with his wife Ntlokwana and one other member of the Enlightened Christian Gathering church. The trio have been accused of money laundering, theft and fraud. Bushiri is reputed to be Africa’s richest religious figure, with an estimated net worth of $150-million. The Continent ISSUE 26. October 24 2020 Page 3 The Week in Numbers 100,000 236,0000 The number of 1.8-billion The number of people who may The number of trees newborns who died in have been exposed in West Africa’s sub-Saharan Africa in to lead poisoning in Sahel and Sahara 2019 due to household Kabwe, Zambia, due deserts. -

{Download PDF} Congo Pdf Free Download

CONGO PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Michael Crichton | 384 pages | 05 Jul 2011 | Cornerstone | 9780099544319 | English | London, United Kingdom Congo () - IMDb From to the country was officially the Republic of Zaire, a change made by then ruler Gen. Mobutu Sese Seko to give the country what he thought was a more authentic African name. Unlike Zaire, however, the name Congo has origins in the colonial period, when Europeans identified the river with the kingdom of the Kongo people, who live near its mouth. Congo subsequently was plunged into a devastating civil war; the conflict officially ended in , although fighting continued in the eastern part of the country. Congo is rich in natural resources. It boasts vast deposits of industrial diamonds, cobalt , and copper; one of the largest forest reserves in Africa; and about half of the hydroelectric potential of the continent. Most of the country is composed of the central Congo basin , a vast rolling plain with an average elevation of about 1, feet metres above sea level. The lowest point of 1, feet metres occurs at Lake Mai-Ndombe formerly Lake Leopold II , and the highest point of 2, feet metres is reached in the hills of Mobayi-Mbongo and Zongo in the north. The basin may once have been an inland sea whose only vestiges are Lakes Tumba and Mai- Ndombe in the west-central region. This part of the country is the highest and most rugged, with striking chains of mountains. The Mitumba Mountains stretch along the Western Rift Valley, rising to an elevation of 9, feet 2, metres.