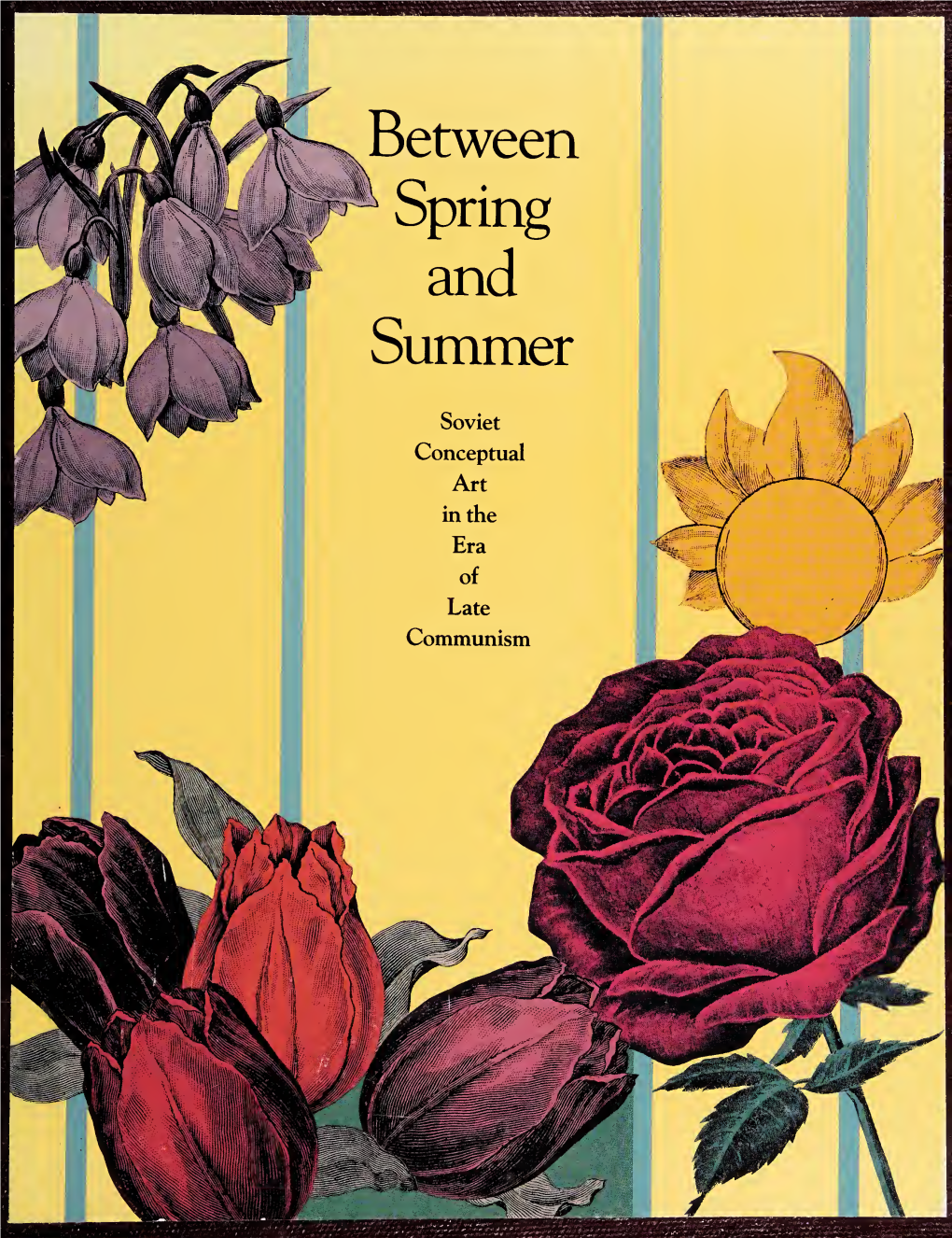

Soviet Conceptual Art in the Era of Late Communism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ilya & Emilia Kabakov

ILYA & EMILIA KABAKOV: NOT EVERYONE WILL BE TAKEN INTO THE FUTURE 18 October 2017 – 28 January 2018 LARGE PRINT GUIDE Please return to exhibition entrance CONTENTS Introduction 3 Room 1 7 Room 2 23 Room 3 37 Room 4 69 Room 5 81 Room 6 93 Room 7 101 Room 8 120 Room 9 3 12 Room 10 5 13 INTRODUCTION 3 Ilya and Emilia Kabakov are amongst the most celebrated artists of their generation, widely known as pioneers of installation art. Ilya Kabakov was born in 1933 in Dnepropetrovsk (now Dnipro) in Ukraine, formerly part of the Soviet Union. When he was eight, he moved to Moscow with his mother. He studied at the Art School of Moscow, and at the V.I. Surikov Art Institute. Artists in the Soviet Union were obliged to follow the officially approved style, Socialist Realism. Wanting to retain his independence, Ilya supported himself as a children’s book illustrator from 1955 to 1987, while continuing to make his own paintings and drawings. As an ‘unofficial artist’, he worked in the privacy of his Moscow attic studio, showing his art only to a close circle of artists and intellectuals. Ilya was not permitted to travel outside the Soviet Union until 1987, when he was offered a fellowship at the Graz Kunstverein, Austria. The following year he visited New York, and resumed contact with Emilia Lekach. Born in 1945, Emilia trained as a classical pianist at Music College in Irkutsk, and studied Spanish Language and Literature at Moscow University before emigrating to the United States in 1973. -

The Conceptual Art Game a Coloring Game Inspired by the Ideas of Postmodern Artist Sol Lewitt

Copyright © 2020 Blick Art Materials All rights reserved 800-447-8192 DickBlick.com The Conceptual Art Game A coloring game inspired by the ideas of postmodern artist Sol LeWitt. Solomon (Sol) LeWitt (1928-2007), one of the key pioneers of conceptual art, noted that, “Each person draws a line differently and each person understands words differently.” When he was working for architect I.M. Pei, LeWitt noted that an architect Materials (required) doesn't build his own design, yet he is still Graph or Grid paper, recommend considered an artist. A composer requires choice of: musicians to make his creation a reality. Koala Sketchbook, Circular Grid, He deduced that art happens before it 8.5" x 8.5", 30 sheets (13848- becomes something viewable, when it is 1085); share two across class conceived in the mind of the artist. Canson Foundation Graph Pad, 8" x 8" grid, 8.5" x 11" pad, 40 He said, “When an artist uses a conceptual sheets, (10636-2885); share two form of art, it means that all of the planning across class and decisions are made beforehand and Choice of color materials, the execution is a perfunctory affair. The recommend: idea becomes a machine that makes the Blick Studio Artists' Colored art.” Pencils, set of 12 (22063-0129); Over the course of his career, LeWitt share one set between two students produced approximately 1,350 designs known as “Wall Drawings” to be completed at specific sites. Faber-Castell DuoTip Washable Markers, set of 12 (22314-0129); The unusual thing is that he rarely painted one share one set between two himself. -

Iowa State Capitol Complex Master Plan I

Iowa State Capitol Complex I Master Plan January 7, 2010 (Amended December 2020) State of Iowa Department of Administrative Services & Capitol Planning Commission Confluence Zimmer Gunsul Frasca Architects LLP Jeffrey Morgan Architecture Studio Tilghman Group Snyder and Associates [ This page intentionally left blank ] Iowa State Capitol Complex Master Plan Master Complex Capitol State Iowa Contents ii Preface 78 Architectural Design 82 Utilities 1 Chapter 1 - The Vision 84 Parking 9 Chapter 2 - Principal Influences on the Plan 88 Transit 10 Historical Development 92 Pedestrian and Bicycle Circulation 16 Capitol Neighborhood 99 Sustainable Development Principles 23 Chapter 3 - Capitol Complex 107 Chapter 4 - Making the Vision a Reality 24 Concept 111 Acknowledgements 28 Approaches and Gateways 30 View Corridors and Streets 117 Appendix A - Transportation Plan 38 Access and Circulation 131 Appendix B - Facility Needs Assessment 45 Landscape Framework Summary 58 Monuments and Public Art 155 Appendix C - Capitol Complex Planning History 62 Site Amenities 64 Signs and Visitor Information 164 Appendix D - Annual Review & Update of Iowa State Capitol Complex 2010 72 Buildings Master Plan i ii Iowa State Capitol Complex Master Plan Master Complex Capitol State Iowa Preface iii Introduction Amended December 2016, 2020 The Iowa State Legislature appropriated funds to the Department of Administrative than fiscal years. Services for updating the 2000 Master Plan for physical facilities on the Iowa State Capitol Complex. The resulting 2010-2060 plan was prepared in close collaboration Beginning in 2015, the Capitol Planning Commission committed to keeping the with the Capitol Planning Commission for its consideration and acceptance. The Master Plan viable and current by annually reviewing the Plan to note accomplished consultant team was led by Confluence and Zimmer Gunsul Frasca Architects goals as well as recognizing evolving changes in conditions and assumptions. -

Art and Power in Putin's Russia

RUSSIA Art and Power in Putin’s Russia BY SASHA PEVAK The separation between art and power in Russia’s recent history has never been clear-cut. Soon after the fall of the USSR, contemporary art, namely actionism in the 90s, openly criticized society and entered the political sphere. This trend continued after Vladimir Putin’s election in 2000. Russian identity politics in the 2000s were based on four pillars: state nationalism with the Putin’s “power vertical”, the vision of Russia as a nation-state, Orthodox religion, and the myth of the Unique Russian Path, reinforced by the notion of “sovereign democracy” and the idea of the omnipresence of a fifth column inside the country 1. The will to consolidate society around these values provoked, according to political scientist Lena Jonson, tensions between the State and culture, especially as far as religious issues were concerned. These issues were the cause of the trials against the exhibitions “Attention! Religion” (2003) and “Forbidden Art – 2006” (2007), shown in Moscow at the Andrei Sakharov Museum and Public Centre. The latter staged temporary events and activities based on the defence of Human Rights. For part of the national opinion, the Centre symbolized democracy in Russia, whereas for others it represented an antipatriotic element, all the more so because it was financed by foreign foundations. In 2014, the Department of Justice catalogued it as a “foreign agent,” on the pretext that it carried out political actions with American subsidies 2. In 2003, the exhibition “Caution, Religion!”, organized by Aroutioun Zouloumian, was vandalized by religious activists several days after the opening 3. -

All These Post-1965 Movements Under the “Conceptual Art” Umbrella

All these post-1965 movements under the “conceptual art” umbrella- Postminimalism or process art, Site Specific works, Conceptual art movement proper, Performance art, Body Art and all combinations thereof- move the practice of art away from art-as-autonomous object, and art-as-commodification, and towards art-as-experience, where subject becomes object, hierarchy between subject and object is critiqued and intersubjectivity of artist, viewer and artwork abounds! Bruce Nauman, Live-Taped Video Corridor, 1970, Conceptual Body art, Postmodern beginning “As opposed to being viewers of the work, once again they are viewers in it.” (“Subject as Object,” p. 199) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9IrqXiqgQBo A Postmodern beginning: Body art and Performance art as critique of art-as-object recap: -Bruce Nauman -Vito Acconci focus on: -Chris Burden -Richard Serra -Carolee Schneemann - Hannah Wilke Chapter 3, pp. 114-132 (Carolee Schneemann and Hannah Wilke, First Generation Feminism) Bruce Nauman, Bouncing Two Balls Between the Floor and Ceiling with Changing Rhythms, 1967-1968. 16mm film transferred to video (black and white, sound), 10 min. Body art/Performance art, Postmodern beginning- performed elementary gestures in the privacy of his studio and documented them in a variety of media Vito Acconci, Following Piece, 1969, Body art, Performance art- outside the studio, Postmodern beginning Video documentation of the event Print made from bite mark Vito Acconci, Trademarks, 1970, Body art, Performance art, Postmodern beginning Video and Print documentation -

Architecture of Downtown Des Moines: Some Highlights from the Twentieth Century and Beyond

Paula Mohr is an architectural historian and directs the certified local government program in Iowa. She is a graduate of the Cooperstown Museum Studies program and the architectural history program at the University of Virginia. Paula is the local co-chair for FORUM 2018. Architecture of Downtown Des Moines: Some Highlights from the Twentieth Century and Beyond By Paula Mohr In its 170-some years, the evolution of Des Moines’ commercial core has paral- leled that of many American cities. Fort Des Moines, an early foothold in terms of Euro-American settlement, today survives only as an archaeological site. Early commercial buildings of wood frame on both the east and west sides of the Des Moines River were replaced with brick later in the nineteenth century. At the turn of the twentieth century another wave of development introduced tall buildings or skyscrapers. In the midst of all this change, we can see the impact of external forces, including architectural ideas from Chicago, the City Beautiful Movement and the contributions of nationally and internationally renowned architects. The “book” on Des Moines’ architecture is still being written. As a result of this constant renewal and rebuild- Youngerman Block (1876), also by Foster, features ing, only a handful of nineteenth century buildings a façade of “Abestine Stone,” a nineteenth-century survive in Des Moines’ downtown. In the Court artificial stone manufactured by the building’s Avenue entertainment area across the river from owner, Conrad Youngerman. The five-story Des the FORUM conference hotel are several notable Moines Saddlery Building (c. 1878), just around examples. -

Shapiro Auctions

Shapiro Auctions RUSSIAN ART AUCTION INCLUDING POSTERS & BOOKS Tuesday - June 15, 2010 RUSSIAN ART AUCTION INCLUDING POSTERS & BOOKS 1: GUBAREV ET AL USD 800 - 1,200 GUBAREV, Petr Kirillovich et al. A collection of 66 lithographs of Russian military insignia and arms, from various works, ca. 1840-1860. Of varying sizes, the majority measuring 432 x 317mm (17 x 12 1/2 in.) 2: GUBAREV ET AL USD 1,000 - 1,500 GUBAREV, Petr Kirillovich et al. A collection of 116 lithographs of Russian military standards, banners, and flags from the 18th to the mid-19th centuries, from various works, ca. 1830-1840. Of varying sizes, the majority measuring 434 x 318mm (17 1/8 x 12 1/2 in.) 3: RUSSIAN CHROMOLITHOGRAPHS, C1870 USD 1,500 - 2,000 A collection of 39 color chromolithographs of Russian military uniforms predominantly of Infantry Divisions and related Artillery Brigades, ca. 1870. Of various sizes, the majority measuring 360 x 550mm (14 1/4 x 21 5/8 in.) 4: PIRATSKII, KONSTANTIN USD 3,500 - 4,500 PIRATSKII, Konstantin. A collection of 64 color chromolithographs by Lemercier after Piratskii from Rossiskie Voiska [The Russian Armies], ca. 1870. Overall: 471 x 340mm (18 1/2 x 13 3/8 in.) 5: GUBAREV ET AL USD 1,200 - 1,500 A collection of 30 lithographs of Russian military uniforms [23 in color], including illustrations by Peter Kirillovich Gubarev et al, ca. 1840-1850. Of varying sizes, the majority measuring 400 x 285mm (15 3/4 x 11 1/4 in.), 6: DURAND, ANDRE USD 2,500 - 3,000 DURAND, André. -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

Global Interiors Living Small & Smart

ASPIRE DESIGN AND HOME JUXTAPOSITION in DESIGN GLOBAL INTERIORS LIVING SMALL & SMART ASPIREMETRO.COM WWW.ASPIREMETRO.COM 61 & INSIDE ON THE MARKET: HUDSON VALLEY | HAWAII | BROOKLYN | NAPA VALLEY universal candor SAN FRANCISCO-BASED DESIGNER JIUN HO COLLABORATES WITH A DECISIVE COUPLE TO RECONFIGURE THEIR ECLECTIC HOME TEXT MICHELE KEITH PHOTOGRAPHY MATTHEW MILLMAN tarting with designer Jiun Ho Swho hails from Malaysia, and the bio-tech executive homeowners, one African-American, his partner German; to such artworks as a larger-than-life sculpture from Cameroon and paintings from Russian conceptualists Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid; to furnishings that include a Kashan carpet from Persia to a Louis XV desk, it’s clear this house would be hard to beat in the “universal” category. Above: Skillfully concealed lighting casts a glow on the hallway’s art collection distinguished by an early-20th-century Baga Nimba shoulder mask from Guinea, West Africa. The stairs, with balustrade designed by Ho, are made of oak as is the flooring. Opposite: Viewed through an arch, the office area features a Louis XV desk. Acquired at auction, with gilt bronze embellishments, it’s made of tulipwood, amaranth and rosewood. Creating a contemporary contrast are lithographs by Antoni Tàpies, acquired by the homeowners at auction. 122 WINTER 2017-18 WWW.ASPIREMETRO.COM 123 In the light-filled living room where curves contrast with straight edges, an oil and tar on canvas by Piero Manzoni, “Genus,” draws attention to the fireplace. 124 WINTER 2017-18 WWW.ASPIREMETRO.COM 125 The homeowners left the color palette and other such crucial elements for Ho to resolve. -

The Island Ostrov

The Island Ostrov Director: Pavel Lungin Writer: Dmitri Sobolev Released: 23 November 2006 (Russia) "He has played so many well-meaning jokes on the locals and other monks, but the grand joke is on him, tricked by God into a life of faithfulness and the healing of others." Synopsis: Somewhere in Northern Russia in a small Russian Orthodox monastery lives a very unusual man. His fellow-monks are confused by his bizarre conduct. Those who visit the island believe that the man has the power to heal, exorcise demons and foretell the future. However, he considers himself unworthy because of a sin he committed in his youth. The film is a parable, combining the realities of Russian everyday life with monastic ritual and routine. http://www.amazon.com/Ostrov-Island-version-English-subtitles/dp/B000LTTOOS Before you watch the film, consider the following questions to guide your reflection: The Island has been perceived around the world, both by film critics and audience members, as a symbolic work for Russia today – a parable of sorts. Pavel Lungin’s The Island was shown in Voronezh with no free seats. The local clergy booked the entire movie theater… A day before the first show, the Metropolitan of Voronezh and Borisoglebsk gave an order to post the AD for the coming premier next to the schedule of worship in all of the city’s forty churches. The parish was surprised: never before were films advertised in churches… Father Andrei, a secretary of the eparchy comments: “The Metropolitan has watched the film and, therefore, we recommend it to the clergy and the parish.” … The show started with a prayer… Prior to the screening everybody crossed themselves… Petr Mamonov, the actor: “To me it means that our church is alive.” The clergy thanked Mamonov. -

Cultural Heritage, Cinema, and Identity by Kiun H

Title Page Framing, Walking, and Reimagining Landscapes in a Post-Soviet St. Petersburg: Cultural Heritage, Cinema, and Identity by Kiun Hwang Undergraduate degree, Yonsei University, 2005 Master degree, Yonsei University, 2008 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2019 Committee Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Kiun Hwang It was defended on November 8, 2019 and approved by David Birnbaum, Professor, University of Pittsburgh, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures Mrinalini Rajagopalan, Associate Professor, University of Pittsburgh, Department of History of Art & Architecture Vladimir Padunov, Associate Professor, University of Pittsburgh, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures Dissertation Advisor: Nancy Condee, Professor, University of Pittsburgh, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures ii Copyright © by Kiun Hwang 2019 Abstract iii Framing, Walking, and Reimagining Landscapes in a Post-Soviet St. Petersburg: Cultural Heritage, Cinema, and Identity Kiun Hwang, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2019 St. Petersburg’s image and identity have long been determined by its geographical location and socio-cultural foreignness. But St. Petersburg’s three centuries have matured its material authenticity, recognizable tableaux and unique urban narratives, chiefly the Petersburg Text. The three of these, intertwined in their formation and development, created a distinctive place-identity. The aura arising from this distinctiveness functioned as a marketable code not only for St. Petersburg’s heritage industry, but also for a future-oriented engagement with post-Soviet hypercapitalism. Reflecting on both up-to-date scholarship and the actual cityscapes themselves, my dissertation will focus on the imaginative landscapes in the historic center of St. -

Exhibition Provides New Insight Into the Globalization of Conceptual Art, Through Work of Nearly 50 Moscow-Based Artists Thinki

EXHIBITION PROVIDES NEW INSIGHT INTO THE GLOBALIZATION OF CONCEPTUAL ART, THROUGH WORK OF NEARLY 50 MOSCOW-BASED ARTISTS THINKING PICTURES FEATURES APPROXIMATELY 80 WORKS, INCLUDING MAJOR INSTALLATIONS, WORKS ON PAPER, PAINTINGS, MIXED-MEDIA WORKS, AND DOCUMENTARY MATERIALS, MANY OF WHICH OF HAVE NOT BEEN PUBLICLY DISPLAYED IN THE U.S. New Brunswick, NJ—February 23, 2016—Through the work of nearly 50 artists, the upcoming exhibition Thinking Pictures will introduce audiences to the development and evolution of conceptual art in Moscow—challenging notions of the movement as solely a reflection of its Western namesake. Opening at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers in September 2016, the exhibition will explore the unique social, political, and artistic conditions that inspired and distinguished the work of Muscovite artists from peers working in the U.S. and Western Europe. Under constant threat of censorship, and frequently engaging in critical opposition to Soviet-mandated Socialist Realism, these artists created works that defied classification, interweaving painting and installation, parody and performance, and images and texts in new types of conceptual art practices. Drawn from the Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection at the Zimmerli, the exhibition features masterworks by such renowned artists as Ilya Kabakov, Komar and Melamid, Eric Bulatov, Andrei Monastyrsky, and Irina Nakhova, and introduces important works by under-represented artists, including Yuri Albert, Nikita Alekseev, Ivan Chuikov, Elena Elagina, Igor Makarevich, Viktor Pivovarov, Oleg Vassiliev, and Vadim Zakharov. Many of the works in the exhibition have never been publicly shown in the U.S., and many others only in limited engagement. Together, these works, created in a wide-range of media, underscore the diversity and richness of the underground artistic currents that comprise ‘Moscow Conceptualism’, and provide a deeper and more global understanding of conceptual art, and its relationship to world events and circumstances.