Read This Book Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cornwall Childminders EYMES Project Case Study Written by Ann Stott with Contributions from Jenny Crow and Childminders in Cornwall

Cornwall Music Service Trust Early Years Music Education Service Phase 4 Research Project. Cornwall Childminders EYMES Project Case Study Written by Ann Stott with contributions from Jenny Crow and Childminders in Cornwall “To what extent can monthly Music Activities impact on Childminders practice and their recognition of and response to children’s innate musicality.” In response to enquiries from childminders attending our EYMES CPD events, the CMST EYMES Cornwall Childminders Project was formed. This supported Childminders and their children across Cornwall and was fully funded by CMST EYMES. Ann Stott (Lead for CMST EYMES) collaborated with Mary-Ann Trethewey (Early Years Childcare Support Assistant, Childminder Support, Cornwall Council) to identify Childminders in Cornwall interested in being part of the project. Six groups of Childminders across the county took part in the project. Some groups already met on a regular basis, others were formed specifically to take part in the project. Some of the groups met in Family Hubs for free whilst others collectively paid for a venue. The groups were located in Launceston, Bodmin, St Austell, St Columb, Falmouth and Porthleven. They ranged in size from 3 Childminders and 5 children to 11 Childminders and 26 children. The children in the groups had an age range of 6 months to 36 months and came from a variety of socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds. The Project Ann Stott (CMST EYMES Lead) delivered the project across the six groups, assisted by Jenny Crow (CMST EYMES Music Leader) at Porthleven from January 2020. Ann met with each group in July 2019 to outline the project delivery and research question. -

Gardens Guide

Gardens of Cornwall map inside 2015 & 2016 Cornwall gardens guide www.visitcornwall.com Gardens Of Cornwall Antony Woodland Garden Eden Project Guide dogs only. Approximately 100 acres of woodland Described as the Eighth Wonder of the World, the garden adjoining the Lynher Estuary. National Eden Project is a spectacular global garden with collection of camellia japonica, numerous wild over a million plants from around the World in flowers and birds in a glorious setting. two climatic Biomes, featuring the largest rainforest Woodland Garden Office, Antony Estate, Torpoint PL11 3AB in captivity and stunning outdoor gardens. Enquiries 01752 814355 Bodelva, St Austell PL24 2SG Email [email protected] Enquiries 01726 811911 Web www.antonywoodlandgarden.com Email [email protected] Open 1 Mar–31 Oct, Tue-Thurs, Sat & Sun, 11am-5.30pm Web www.edenproject.com Admissions Adults: £5, Children under 5: free, Children under Open All year, closed Christmas Day and Mon/Tues 5 Jan-3 Feb 16: free, Pre-Arranged Groups: £5pp, Season Ticket: £25 2015 (inclusive). Please see website for details. Admission Adults: £23.50, Seniors: £18.50, Children under 5: free, Children 6-16: £13.50, Family Ticket: £68, Pre-Arranged Groups: £14.50 (adult). Up to 15% off when you book online at 1 H5 7 E5 www.edenproject.com Boconnoc Enys Gardens Restaurant - pre-book only coach parking by arrangement only Picturesque landscape with 20 acres of Within the 30 acre gardens lie the open meadow, woodland garden with pinetum and collection Parc Lye, where the Spring show of bluebells is of magnolias surrounded by magnificent trees. -

CORNWALL. [ KELJ Y's

1180 SHO CORNWALL. [ KELJ_y's SHOPKEEPERS-continued. Staple John, 69 Pydar street, Truro Thomas Nicholas, Trequite, St. Kew, Rowe Wm. St. Blazey, Par Station R.S.O Stentiford H. Gerrans,Grampound Road Wadebridge R.S.O Rowett Thos. Market st. East Looe R.S.O Stephens Edward Bloye, Latchley, Gun- Thomas Richd. Southgate st. Redruth Rowland Thomas, Coppetthorne, Pound- nislake, Tavistock Thomas Richard, Tregenna pi. St. Ives stock, Stratton R.S.O Stephens Miss Eva, Fore !!treet, St. Thomas Samuel, High street, Penzance Rowling John, Leeds Town, Hayle Columb Major R.S.O Thomas S. D. 79 Killigrew st. Falmouth Rowse J.St. Blazey gate,ParStationR.S.O Stephens Mrs. Jane, 76 Plain-an- Thomas Thomas, Church town, Zennor, Row-e J. L. St. Blazey, ParStation R.S.O Gwarry, Redruth St. Ives R.S.O Rule Miss H. Condurrow, Camborne Stephens John, Godolphin, Helston Thomas William, Carnkie, Redruth Rule Mrs. Mary Ann, Troon, Camborne Stephens Jonathan, Millbrook, Maker, Thomas Wm. Germoe, Marazion R.S.O RundelMrs.E.St.Blazey,ParStationR.S.O Devonport Thorne William,Fore st.East Looe R.S.O Rundle Mrs. F. St. Eval, St. Jssey R.S.O Stephens Mrs. Maria, St. Blazey, Par Tingcombe George, Camelford Rundle Miss G. J. Heiston rd. Penryn Station R.S.O Tom Henry, St. Mabyn, Bodmin Rundle Mrs. J. Trebollett, Launceston Stephens Mrs. Rebecca, Vicarage, St. Toman Mrs. John, Chapel street, Rundle J. H. St. Thomas street, Penryn Agnes, Scorrier R.S.O Newlyn, Penzance Ruse John, Medrase, Camelford Stephens Richard, Towan cross, Mount, Toms Mrs. Eliza, St. -

FEBRUARY 2020 SIGN up to OUR MAILINGS HERE CORONAVIRUS GUIDANCE GENERAL SYNOD AGREES 2030 the Church of England Has Offered Advice to Parishes

OUR NEWS FEBRUARY 2020 SIGN UP TO OUR MAILINGS HERE CORONAVIRUS GUIDANCE GENERAL SYNOD AGREES 2030 The Church of England has offered advice to parishes. ‘NET ZERO’ CARBON TARGET This page (click here) on the national church website will be updated to reflect The Church of England’s General Synod has set new any change in circumstance. The threat posed by Coronavirus targets for all parts of the church to work to become (COVID-19) has been assessed by the carbon ‘net zero’ by 2030. Chief Medical Officer as ‘moderate’. This permits the Government to plan for all eventualities. The risk to individuals At its February 2020 meeting, An amendment by Canon Prof Martin remains low. members voted in favour of a revised Gainsborough (Bristol) introduced a Churches should already be following date encouraging all parts of the more ambitious target date of 2030, best-hygiene practices that include Church of England to take action and fifteen years ahead of the original advising parishioners with coughs and ramp-up efforts to reduce emissions. proposal. The Church of England has sneezes to refrain from handshaking also announced an energy footprinting during The Peace and to receive A motion approved today called for tool for parishes to calculate their Communion in one kind only. urgent steps to examine requirements carbon footprint. to reach the new target, and draw up + MORE INFORMATION IS AVAILABLE an action plan. + READ MORE HERE BISHOP PHILIP ISSUES SAFEGUARDING STATEMENT “The thief comes only to steal write here has been reviewed both If the gospel is about human and kill and destroy. -

Penwith Statement 2 February 1998

CORNWALL COUNTY COUNCIL PUBLIC RIGHTS OF WAY NATIONAL PARKS AND ACCESS TO THE COUNTRYSIDE ACT 1949 COUNTRYSIDE ACT 1968 WILDLIFE AND COUNTRYSIDE ACT 1981 REVISED STATEMENT PENWITH DISTRICT Parish of GWINEAR-GWITHIAN Relevant date for the purposes of this revised Definitive Statement: 2nd February 1998 _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ NO. LOCATION AVERAGE MIN WIDTH WIDTH _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1 FP from road west of Barripper to Coswinsawsin Lane 3'0" 2 FP from road south west of Carnhell Green to BR 49 at Cathebedron 3'0" 3 FP from Shaft Downs to BR 49 3'0" 4 FP from road south of Halancoose to B3280 3'0" 5 FP from BR 49 south of Drewollas to FP 6 3'0" 6 FP from BR 49 north east of Gwinear Downs to FP 5 2'6" 7 FP from road south of Deveral to BW 52 west of Calloose - 8 FP from south of Taskus to Parish Boundary 2'6" 9 FP from BR 54 at Trenerth to BW 52 at Calloose Caravan Park 2'0" 1.0m 10 FP from Tregotha to Parish Boundary and Hayle FP 44 - 11 FP from south of Gwinear to Deverell Road west of Henvor 2'6" 12 FP from BR 49 at Drewollas to Reawla Lane (Wall) 2'6" 13 FP from Gwinear to road north of Relistien 3'0" 14 FP from Rosewarne to Lanyon Gate 3'0" 15 FP from Lanyon Gate to road north of Carnhell Green - 16 FP and BR from Gwinear via Lanyon Farm to former Gwinear Road Station 3'0" 1.5m 17 FP from Higher Trevaskis (BR16) to lane west of Trevaskis 2'6" 18 FP from BR 16 north of Lanyon to south of Trenowin 2'6" 19 FP from Gwinear to Polkinghorne 2'6" 20 FP from Gwinear via Trungle to Parish Boundary at Angarrack 3'0" Parish of GWINEAR-GWITHIAN Relevant Date 2nd February 1998 - Sheet 2 _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ NO. -

![CORNWALL.] FARMERS Continued](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9312/cornwall-farmers-continued-2239312.webp)

CORNWALL.] FARMERS Continued

TRADES DIRECTORY.] 959 FAR [CORNWALL.] FARMERS continued. Treffry Mrs. Grace, Peneskin, Ruan TrembathJames, Carnequidden & Bos- Tbomas Thomas, Mudianvean, St. Laniborne, Grampouod crege, Gulval, Penzance Martin-in-Meneage, Helston Treffry J.GovilyMinor,Cuby,Grrnpound Trembath James, Menwidden, Ludgvan, Thomas Tbos. Penmarth, Carnmenellis, Tregaskis Samuel, Tregonce, St. Issey Penzance Redruth Tregear Edward,Green,St.Mary's,Scilly Trembath J. Ninnis, Gwennap, Redruth Thomas Thos.Spittal,St.Mabyn,Bodmin Tregear James, Boswarlas, St. Just-in- Trembath J.Tremhath, Morvah,Penznce ThomasW.Bojewyan,Pendeen,Penzance Penwith, Penzance Trembath John, Kenwyn, Truro Thomas Wm. Cadwin, Lanivet, Bodmiu TregearJohn,Pentreath,Breage,Helston Trembath John, Pendeen, Penzance Thomas William, Godolphin, Helston Tregear William, Boswarlas, St. Just- Trembath Matthew,Bojewyan,Pendeen, Thomas W.Lidcott, Cardinham, Bodmin in-Penwith, Penzance Penzance Thomas W. Mulberry, Lanivet, Bodmin Tregear.William, Green,St.Mary's,Scilly Trembath Richard, Pedneventon, Thomas William, N anpean, St. Tregellas J .Church tn. St.Agnes,Scorrier Madron, Penzance Stephens-in-Branwell Tregenza T. Mylor brdg. Mylor, Falmth Trembath Richard, Trevilley,St.Sennen, Thomas W . .Ninnis, Wendron, Helston Treglown Henry, Bolenowe, Treslothan, Penzance Thomas William, Park Ventonsah, Camborne Trembath William, Tresvennack, St. Mullion, Helst.on TregoningArchelaus,Hugos, Kea, Truro Paul, Penzance Thomas W. Trereen, Zennor, St. Ives Tregoning Mrs. Elizabeth, Colvadnack, Tremhath William David, Portb, St. Thomas W.Wheel Wreeth,Lelant,Hayle Carnmenellis, Redruth Anthony-in-Roseland, Gramponnd Thomas Wm. Zelah, St. Alien, Truro Tregoning Henry, Tregilsoe, St. Hilary, Tremewan William,Horrows,Luxulyan, Thomas W. H. Higher Market st. Penryn M arazion Bodmin Thomas William Henry, Lancarrow, Tregoning Mrs. Maria, Walkey trees, TremewenNicholas, Trewey, St. Levan, Carnmenellis, Redruth St. -

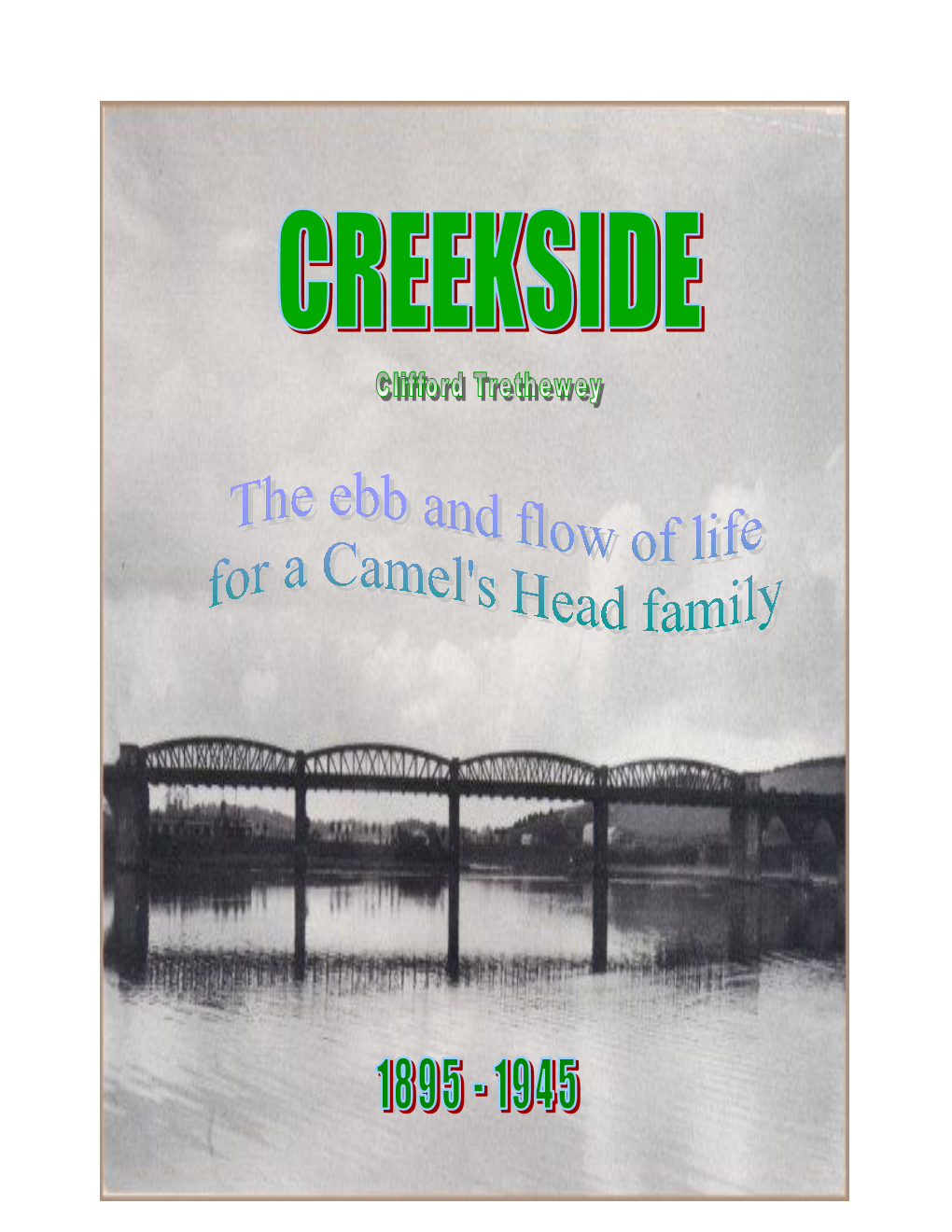

Clifford Trethewey

Clifford Trethewey BOOK 2 Introduction Plymouth’s First Generation It really was quite a sight. Black and white hulls moored three and four abreast, without their spars, as far as the eye could see. John and Ann had been to Plymouth Dock before when the war with France was still being fought and the Hamoaze was devoid of ships. Three years had passed since that time and John was carrying a small boy who had never seen a ship before. That boy would eventually become the father of four brothers who would all join Victoria’s Navy, but that was still years into the future. Ann’s passenger was asleep in a carrying basket as the boatman helped her into the boat with all their worldly possessions. When he pushed them off the beach and deployed his oars before the tide could capture their hesitation, he set the boat’s head towards North Corner. There, they would set foot in Devon and the new life that awaited them. Of course this is a Family History that is more than 200 years old. Facts and records are scarce. I am fortunate in the fact that John and Ann had EIGHT children, but they also buried three of them, yet every record survives to follow their path from house to house and job to job. No Family Historian encourages conjecture, but neither does any family exist without the question ‘why did they do that?’ It has been particularly difficult to suggest a way in which John became a stonemason. He could not have done it without help and in a strange and overwhelming town that help was most likely to come from a relative or a friend. -

The Penthouse

THE PENTHOUSE THE PENTHOUSE, THE PENTHOUSE • CYAN • PORTHCURNO • PENZANCE • CORNWAL • TR19 6JU THE PENTHOUSE COMPRISES EXTENSIVE LATERAL LIVING BENEFITING WITH PANORAMIC SEA VIEWS TO LOGANS ROCK. • Situated above Porthcurno beach • Sea views • Three Bedrooms • Ground source heating • Balcony • Two designated parking spaces • Close to the Minack theatre DISTANCES Minack Theatre- 0.2 miles St Buryan – 4 Sennen Cove – 4.5 Lamorna Cove – 6.5 Mousehole – 8.5 Newlyn – 8.5 Penzance – 10 St Ives – 17.4 Cornwall Airport (Newquay) – 51 THE LOCATION balcony area off the kitchen perfect for those warm summer evenings. The kitchen and sitting room area have outstanding The Penthouse apartment is located within walking distance sea views to Logans Rock. The property has two designated of Porthcurno Beach. Described by Good Beach Guide parking spaces, three good sized double bedrooms with two 2015 as being a paradise, Porthcurno is located in the far en-suites, guest bathroom, storage space, kitchen/dining west of Cornwall and has won many awards: it’s easy to see area, a balcony overlooking the sea and Logans Rock and a why with its gorgeous fine soft white sand and turquoise communal outside area overlooking the sea at the end of the water. Porthcurno has the renowned Minack theatre built in car park perfect for barbecues or a picnic. the 1920s by theatrical visionary Rowena Wade, which can be visited all year round. The property has awe-inspiring scenery, coastline, arts scene, legendary surfing. This apartment would make the perfect Another famous attraction is Logans Rock, famous for its 80 lock up and leave or a holiday investment. -

Penwith Introduc on 2019

26/04/2019 Introduction Introducon Penwith 2019 The Penwith locality stretches from St Ives on the North Coast to Marazion on the South Coast. The locality includes the towns of Penzance and Hayle and the Key Messages small rural town of St Just. West Cornwall Hospital in Penzance is a 8 GP pracces, 2 of which are dispensing satellite hospital, providing a 24-hour Urgent Care Centre, amongst other 65,170 residents are registered at the GP Pracces facilies. Addionally there is St Michael’s hospital, in Hayle, providing a range of Over 12,000 residents registered at Stennack Surgery specialist services. Obesity is the worst long term condion Edward Hain community hospital, is located in St Ives along with a minor injury 27.5% of paents are elderly unit at the Stennack Surgery. Currently 644 care home beds, 1,063 new units planned The main general hospital for Cornwall, Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust, Treliske, is based in Truro. 65,170 12.43% Registered Paents GP Pracces Paents Obese Name Address Town Postcode Status/Dispensing ALVERTON PRAC 7 ALVERTON TERRACE PENZANCE TR18 4JH Pracce - Non Disp BODRIGGY HEALTH CTR 60 QUEENSWAY HAYLE TR27 4PB Pracce - Non Disp CAPE CORNWALL SURGERY ST.JUST-IN-PENWITH PENZANCE TR19 7HX Pracce - Disp MARAZION SURGERY GWALLON LANE MARAZION TR17 0HW Pracce - Disp MORRAB SURGERY 2 MORRAB ROAD PENZANCE TR18 4EL Pracce - Non Disp 27.5% ROSMELLYN SURGERY ALVERTON TERRACE PENZANCE TR18 4JH Pracce - Non Disp 1,063 STENNACK SURGERY THE OLD STENNACK SCHOOL ST.IVES TR26 1RU Pracce - Non Disp Care Home Paents SUNNYSIDE SURGERY HAWKINS ROAD PENZANCE TR18 4LT Pracce - Non Disp Units Planned 65+ Introducon Populaon Elderly Populaon 1/1 26/04/2019 Population Populaon Penwith 2019 The latest figures (2017) show that the populaon for the Penwith Locality is 63,936, with a difference of almost 3,000 more female than male. -

Cornish Language & Names in Family Research

TALK TO THE CORNISH INTERESTS MEETING 17th June, 2000 THE CORNISH LANGUAGE AND NAMES IN FAMILY RESEARCH Dohajéth da. Hedhyu mý a vyn clappya yn-kever an Yéth Gernewek coth ha keltek. Pyth dysquedhyans a'n Yéth Gernewek a vynnas bos gwelas war ün vysytya dhe Pow Kernow? Good afternoon. Today I will talk about the ancient Celtic Cornish language. What evidence of the Cornish language would be seen on a visit to Cornwall? OK, you may be fortunate enough to attend a church service in Cornish at Truro Cathedral, or seeking out a relaxing place after a hard day’s touring you may stumble upon a small group in a pub talking animatedly in Cornish. The main contact however will of course be in names: People names. We’ve talked about that before here. And Place Names How are Cornish place names different to English place names? Saying "By tre, pol and pen shall ye know most Cornishmen" Cornwall has noticeably different place names from neighbouring England (about 80% of place names in Cornwall are derived from the Celtic Cornish language, most of the remainder being either from English or Norman French. These names are similar in many respects to Welsh and Breton names (Cornish, Breton and Welsh languages are closely related). Examples: Landevennec (Brittany) and Landewednak (Cornwall); Pendine (Wales), Pendeen (Cornwall). What are Cornish Place Names like? Typically, Cornish place names start with elements such as tre (settlement), pol (pool or lake) and pen (hill). Unlike English place names, Cornish ones are structured in 'reverse order' by comparison with English place names. -

Ancient Sites of West Penwith from the Map of the Ancient Sites and Alignments of West Penwith 9Th October 2015

Ancient Sites of West Penwith From the Map of the Ancient Sites and Alignments of West Penwith 9th October 2015. www.ancientpenwith.org STONE CIRCLES Boleigh -5.590485 50.064483 Stone circle (missing). Possibly seven stones. SW 43142444. 50.064481N 5.5905247W. http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=423062 Stone circle. SW 4122 2736. 50.089857N 5.619272W. www.themodernantiquarian.com/site/229/boscawenun.html http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boscawen-Un BOSCAWEN-UN -5.619292 50.089841 http://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=22 http://www.ancient-wisdom.co.uk/englandboscawen.htm http://www.cornishancientsites.com/Boscawen- un%20circle.pdf Bosiliack -5.58334 50.133124 Bosiliack, destroyed stone circle. SW440320 50.132710193048N 5.583597772401W www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=689 Botallack -5.686852 50.139079 Stone circles, destroyed. SW36693311. 50° 8' 19.87" N 5° 41' 7.82" W. www.themodernantiquarian.com/site/10317/botallack.html Higher Trevorian -5.6120931 50.0802572 Destroyed stone circle (marked on old OS maps). SW 4168 2626. 50.080184N 5.612112W www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=23419 Unique holed stone, with menhirs and stones - formerly a stone circle. SW 4264 3493. 50.158134N 5.605106W. http://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?x=142600&y=035000 http://www.megalithics.com/england/menantol/mentmain.htm MEN AN TOL -5.604428 50.158561 http://www.themodernantiquarian.com/site/236/menantol.html http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M%C3%AAn-an-Tol http://www.saintsandstones.net/stones- menantol-journey.htm Stone circle. SW43262458. 50.065789N 5.588945W. http://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?x=143200&y=024600 MERRY MAIDENS -5.588726 50.065139 http://www.themodernantiquarian.com/site/307/merry_maidens.html http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Merry_Maidens http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=422900 Boskednan Stone circle. -

LAND Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

LAND bus time schedule & line map LAND Lelant Downs View In Website Mode The LAND bus line (Lelant Downs) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Lelant Downs: 5:30 PM (2) Penzance: 8:25 AM - 4:30 PM (3) Penzance: 8:35 AM - 5:00 PM (4) St Ives: 6:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest LAND bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next LAND bus arriving. Direction: Lelant Downs LAND bus Time Schedule 93 stops Lelant Downs Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 5:30 PM Monday 5:30 PM Bus Station, Penzance Tuesday 5:30 PM Jubilee Pool, Penzance Green Street, Penzance Civil Parish Wednesday 5:30 PM Lidl, Penzance Thursday 5:30 PM Western Promenade Road, Penzance Civil Parish Friday 5:30 PM Lidden Road, Penzance Saturday 5:30 PM New Road, Penzance Civil Parish Newlyn Art Gallery, Newlyn Florence Place, Penzance Civil Parish LAND bus Info Newlyn Bridge, Newlyn Direction: Lelant Downs 2 The Strand, Penzance Civil Parish Stops: 93 Trip Duration: 188 min Chywoone Hill, Newlyn Line Summary: Bus Station, Penzance, Jubilee Pool, Penzance, Lidl, Penzance, Lidden Road, Penzance, Gwavas Crossroads, Newlyn Newlyn Art Gallery, Newlyn, Newlyn Bridge, Newlyn, Chywoone Hill, Newlyn, Gwavas Crossroads, Newlyn, Long Row, She∆eld Long Row, She∆eld, Lamorna Pottery, Lamorna, Lamorna Turn, Lamorna, Menwinian, Boskenna, Lamorna Pottery, Lamorna Merry Maidens, Boskenna, Post O∆ce, St Buryan, Kew Pendra, St Buryan, Westmoor, Sparnon, Crean Lamorna Turn, Lamorna Turn, Sparnon, Lamorna Junction, Sparnon, Bus Shelter, Treen, Trethewey, The Valley, Porthcurno, Car Menwinian, Boskenna Park, Porthcurno, The Valley, Porthcurno, Trethewey, Little Trethewey, Trethewey, Tresco, Polgigga, Skewjack, Trevescan, The Little Barn Cafe, Trevescan, Merry Maidens, Boskenna Car Park, Land's End, Sea View Holiday Park, Sennen, First And Last Inn, Sennen, First And Last Post Post O∆ce, St Buryan O∆ce, Sennen, Maria's Lane, Sennen, Sennen Cove, Galligan Lane, St.