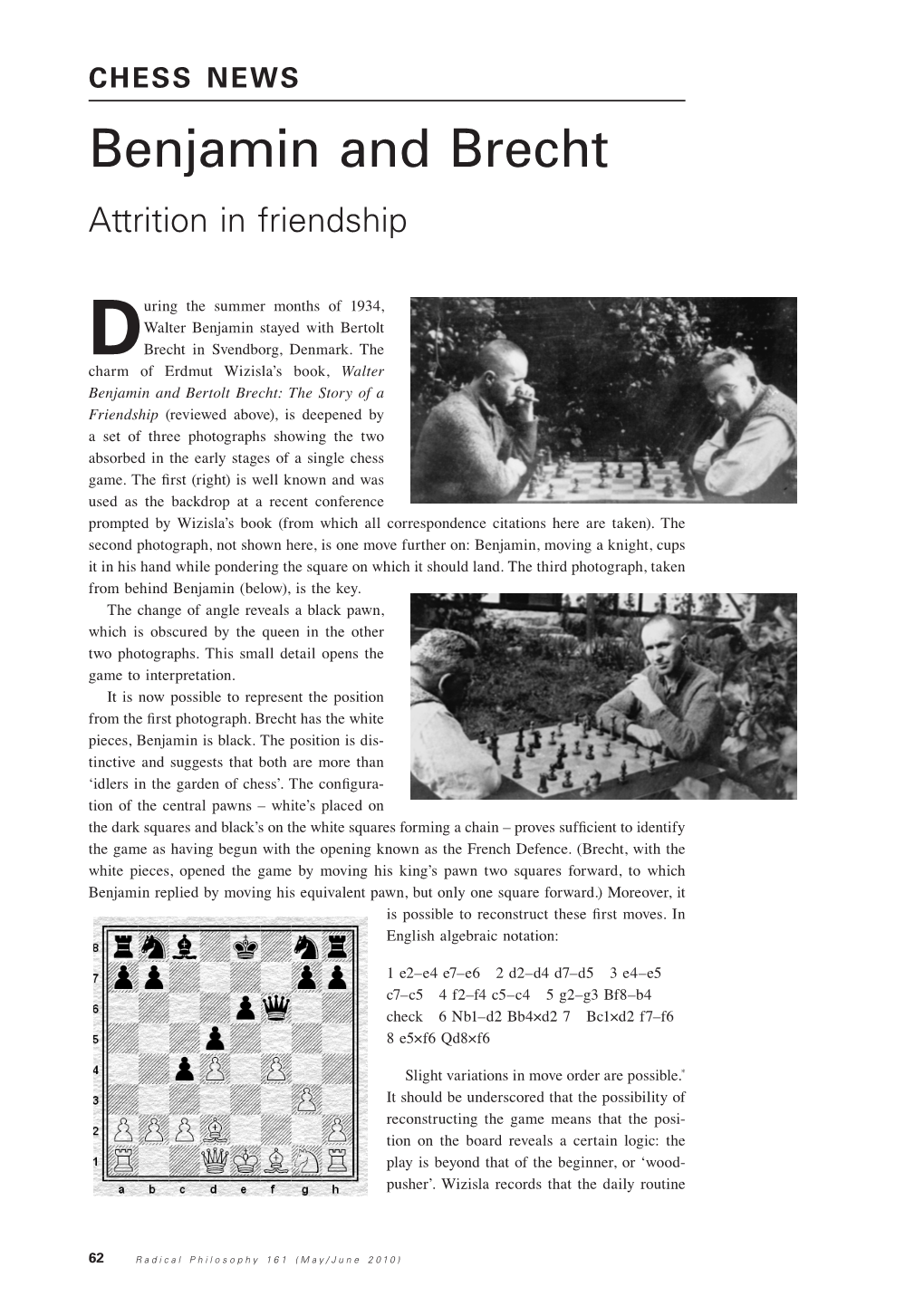

Benjamin and Brecht Attrition in Friendship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Combinatorial Game Theoretic Analysis of Chess Endgames

A COMBINATORIAL GAME THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF CHESS ENDGAMES QINGYUN WU, FRANK YU,¨ MICHAEL LANDRY 1. Abstract In this paper, we attempt to analyze Chess endgames using combinatorial game theory. This is a challenge, because much of combinatorial game theory applies only to games under normal play, in which players move according to a set of rules that define the game, and the last player to move wins. A game of Chess ends either in a draw (as in the game above) or when one of the players achieves checkmate. As such, the game of chess does not immediately lend itself to this type of analysis. However, we found that when we redefined certain aspects of chess, there were useful applications of the theory. (Note: We assume the reader has a knowledge of the rules of Chess prior to reading. Also, we will associate Left with white and Right with black). We first look at positions of chess involving only pawns and no kings. We treat these as combinatorial games under normal play, but with the modification that creating a passed pawn is also a win; the assumption is that promoting a pawn will ultimately lead to checkmate. Just using pawns, we have found chess positions that are equal to the games 0, 1, 2, ?, ", #, and Tiny 1. Next, we bring kings onto the chessboard and construct positions that act as game sums of the numbers and infinitesimals we found. The point is that these carefully constructed positions are games of chess played according to the rules of chess that act like sums of combinatorial games under normal play. -

Parallel Chess Searching and Bitboards

Parallel Chess Searching and Bitboards David Ravn Rasmussen August 2004 Abstract In order to make chess programs faster and thus stronger, the two approaches of parallelizing the search and of using clever data structures have been suc- cessful in the past. In this project it is examined how the use of a specific data structure called a bitboard affects the performance of parallel search. For this, a realistic bitboard chess program with important modern enhance- ments is implemented, and several experiments are done to evaluate the performance of the implementation. A maximum speedup of 9.2 on 22 pro- cessors is achieved in one experiment and a maximum speedup of 9.4 on 12 processors is achieved in another experiment. These results indicate that bitboards are a realistic choice of data structure in a parallel chess program, although the considerable difference in the two results suggests that more research could be done to clarify what factors affect such an implementation, and how. I II Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 The Game Of Chess 5 2.1 TheBoard............................. 6 2.2 TheArmies ............................ 6 2.3 TheMoves............................. 6 2.3.1 TheBishop ........................ 7 2.3.2 TheRook ......................... 7 2.3.3 TheQueen ........................ 8 2.3.4 TheKnight ........................ 8 2.3.5 TheKing ......................... 8 2.3.6 ThePawn ......................... 10 2.4 TheEnd.............................. 11 3 Game Trees and Searching 13 3.1 GameTrees ............................ 13 3.2 SearchAlgorithms ........................ 15 3.2.1 Minimax.......................... 16 3.2.2 Negamax ......................... 18 3.2.3 Evaluation......................... 18 3.2.4 Alpha-BetaSearch . 20 4 Search Algorithm Improvements 25 4.1 AspirationWindows . -

1 Najdorf Sicilian Focus on the Critical D5 Squar One the Most Common Openings in the Past 50 Years Is the Najdorf Variation Of

1 Najdorf Sicilian will try to keep full control over the d5 Focus on the Critical d5 Squar square, and try to maintain the possibility of placing and keeping a piece One the most common openings in the on d5. Fully controlling the d5 square past 50 years is the Najdorf variation of allows white to affect both sides of the the Sicilian Defense. The Najdorf offers board. In order to assure that control, many different possibilities, starting from white wants to trade off black pieces extremely sharp, poison pawn variation that can control d5. For example, he (1. e4, c5 2. nf3 d6 3. d4 cxd4 4. Nxd4 wants to play with Bg5, in order to trade Nf6 5. Nc3 a6 6. Bg5 e6 7. f4 Qb6 8. off the Knight on f6. He also will Qd2 Qxb2! ) to extremely positional lines increase the number of his own pieces (1. e4, c5 2. nf3 d6 3. d4 cxd4 4. Nxd4 that can control d5, with maneuvers like Nf6 5. Nc3 a6 6. Be2 e5 7. Nb3 ... ) bishop to c4, then b3, and the knight on Somewhere between those two lines is f3 going to d2-c4-e3. It seems that white the following position, which I will try to has full control of the situation. So why explain. 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 does black choose to create this pawn 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be3 e5 7.Nf3 structure? The answer is because this is Diagram one of the rare Sicilian pawn structures abcdef gh that gives the black side a slight space advantage. -

Super Human Chess Engine

SUPER HUMAN CHESS ENGINE FIDE Master / FIDE Trainer Charles Storey PGCE WORLD TOUR Young Masters Training Program SUPER HUMAN CHESS ENGINE Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Power Principles...................................................................................................................................... 4 Human Opening Book ............................................................................................................................. 5 ‘The Core’ Super Human Chess Engine 2020 ......................................................................................... 6 Acronym Algorthims that make The Storey Human Chess Engine ......................................................... 8 4Ps Prioritise Poorly Placed Pieces ................................................................................................... 10 CCTV Checks / Captures / Threats / Vulnerabilities ...................................................................... 11 CCTV 2.0 Checks / Checkmate Threats / Captures / Threats / Vulnerabilities ............................. 11 DAFiii Attack / Features / Initiative / I for tactics / Ideas (crazy) ................................................. 12 The Fruit Tree analysis process ............................................................................................................ -

Positional Attacks

Positional Attacks Joel Johnson Edited by: Patrick Hammond © Joel Johnson, January 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from Joel Johnson. Edited by: Patrick Hammond Cover Photography: Barry M. Evans Cover Design and Proofreading: Joel Johnson Game Searching: Joel Johnson, Richard J. Cowan, William Parker, Nick Desmarais Game Contributors: Brian Wall, Jack Young, Clyde Nakamura, James Rizzitano, Keith Hayward, Hal Terrie, Richard Cowan, Jesús Seoane, William Parker, Domingos Perego, Danielle Rice Linares Diagram and Linares Figurine fonts ©1993-2003 by Alpine Electronics, Steve Smith Alpine Electronics 703 Ivinson Ave. Laramie, WY 82070 Email: Alpine Chess Fonts ([email protected]) Website: http://www.partae.com/fonts/ Pressure Gauge graphic Image Copyright Araminta, 2012 Used under license from Shutterstock.com In Memoriam to my step dad and World War II Navy, Purple Heart Recipient, Theodore Kosiavelon, 12/22/1921 – 11/09/2012 CONTENTS Preface 7 Kudos 7 Brian Wall 8 Young Rising Stars 27 Daniil Dubov 27 Wei Yi 30 Section A – Pawn Roles 36 Pawn Structure 37 Ugliest Pawn Structure Ever? 38 Anchoring 41 Alien Pawn 48 Pawn Lever 63 Pawn Break 72 Center Pawn Mass 75 Isolated Pawn 94 Black Strategy 95 White Strategy 96 Eliminate the Isolated Pawn Weakness with d4-d5 96 Sacrifices on e6 & f7 , Often with f2-f4-f5 Played 99 Rook Lift Attack 104 Queenside Play 111 This Is Not Just -

Course Notes and Summary

FM Morefield’s Chess Curriculum: Course Review This PDF is intended to be used as a place to review the topics covered in the course and should not be used as a replacement. Feel free to save, print, or distribute this PDF as needed. Section 1: Background Information History ● Chess is widely assumed to have originated in India around the seventh century. ● Until the mid-1400s in Europe, chess was known as shatranj, which had different rules than modern chess. ● Some well-known authors and chess players from that time period are Greco, Lucena, and Ruy Lopez. ● The Romantic Era lasted from the late 18th century until the middle of the 19th century, and was characterized by sacrifices and aggressive play. ● Chess has widely been considered a sport since the late 1800s, when the World Chess Championship was organized for the first time. Other ● Chess is considered a game of planning and strategy because it is a game with no hidden information, where you and your opponent have the same pieces, so there is no luck. ● Studying chess seriously can bring you many benefits, but simply playing it won’t make you smarter. Section 2: Rules of the Game Setting Up the Board ● There are sixty-four squares on the board, and thirty-two pieces (sixteen per player). ● Each player’s pieces are made up of eight pawns, two knights, two bishops, two rooks, a queen, and a king. ● There are two players, Black and White. White moves first. ● If you’re using a physical board, rotate the board until there is a light square on the bottom right for each player. -

Chess Rules Ages 10 & up • for 2 Players

Front (Head to Head) Prints Pantone 541 Blue Chess Rules Ages 10 & Up • For 2 Players Contents: Game Board, 16 ivory and 16 black Play Pieces Object: To threaten your opponent’s King so it cannot escape. Play Pieces: Set Up: Ivory Play Pieces: Black Play Pieces: Pawn Knight Bishop Rook Queen King Terms: Ranks are the rows of squares that run horizontally on the Game Board and Files are the columns that run vertically. Diagonals run diagonally. Position the Game Board so that the red square is at the bottom right corner for each player. Place the Ivory Play Pieces on the first rank from left to right in order: Rook, Knight, Bishop, Queen, King, Bishop, Knight and Rook. Place all of the Pawns on the second rank. Then place the Black Play Pieces on the board as shown in the diagram. Note: the Ivory Queen will be on a red square and the black Queen will be on a black space. Play: Ivory always plays first. Players alternate turns. Only one Play Piece may be moved on a turn, except when castling (see description on back). All Play Pieces must move in a straight path, except for the Knight. Also, the Knight is the only Play Piece that is allowed to jump over another Play Piece. Play Piece Moves: A Pawn moves forward one square at a time. There are two exceptions to this rule: 1. On a Pawn’s first move, it can move forward one or two squares. 2. When capturing a piece (see description on back), a Pawn moves one square diagonally ahead. -

Birth of the Chess Queen C Marilyn Yalom for Irv, Who Introduced Me to Chess and Other Wonders Contents

A History Birth of the Chess Queen C Marilyn Yalom For Irv, who introduced me to chess and other wonders Contents Acknowledgments viii Introduction xii Selected Rulers of the Period xx part 1 • the mystery of the chess queen’ s birth One Chess Before the Chess Queen 3 Two Enter the Queen! 15 Three The Chess Queen Shows Her Face 29 part 2 • spain, italy, and germany Four Chess and Queenship in Christian Spain 39 Five Chess Moralities in Italy and Germany 59 part 3 • france and england Six Chess Goes to France and England 71 v • contents Seven Chess and the Cult of the Virgin Mary 95 Eight Chess and the Cult of Love 109 part 4 • scandinavia and russia Nine Nordic Queens, On and Off the Board 131 Ten Chess and Women in Old Russia 151 part 5 • power to the queen Eleven New Chess and Isabella of Castile 167 Twelve The Rise of “Queen’s Chess” 187 Thirteen The Decline of Women Players 199 Epilogue 207 Notes 211 Index 225 About the Author Praise Other Books by Marilyn Yalom Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher Waking Piece The world dreams in chess Kibitzing like lovers Pawn’s queened redemption L is a forked path only horses lead. Rook and King castling for safety Bishop boasting of crossways slide. Echo of Orbit: starless squared sky. She alone moves where she chooses. Protecting helpless monarch, her bidden skill. Attacking schemers, plotters, blundered all. Game eternal. War breaks. She enters. Check mate. Hail Queen. How we crave Her majesty. —Gary Glazner Acknowledgments This book would not have been possible without the vast philo- logical, archaeological, literary, and art historical research of pre- vious writers, most notably from Germany and England. -

Reshevsky Wins Playoff, Qualifies for Interzonal Title Match Benko First in Atlantic Open

RESHEVSKY WINS PLAYOFF, TITLE MATCH As this issue of CHESS LIFE goes to QUALIFIES FOR INTERZONAL press, world champion Mikhail Botvinnik and challenger Tigran Petrosian are pre Grandmaster Samuel Reshevsky won the three-way playoff against Larry paring for the start of their match for Evans and William Addison to finish in third place in the United States the chess championship of the world. The contest is scheduled to begin in Moscow Championship and to become the third American to qualify for the next on March 21. Interzonal tournament. Reshevsky beat each of his opponents once, all other Botvinnik, now 51, is seventeen years games in the series being drawn. IIis score was thus 3-1, Evans and Addison older than his latest challenger. He won the title for the first time in 1948 and finishing with 1 %-2lh. has played championship matches against David Bronstein, Vassily Smyslov (three) The games wcre played at the I·lerman Steiner Chess Club in Los Angeles and Mikhail Tal (two). He lost the tiUe to Smyslov and Tal but in each case re and prizes were donated by the Piatigorsky Chess Foundation. gained it in a return match. Petrosian became the official chal By winning the playoff, Heshevsky joins Bobby Fischer and Arthur Bisguier lenger by winning the Candidates' Tour as the third U.S. player to qualify for the next step in the World Championship nament in 1962, ahead of Paul Keres, Ewfim Geller, Bobby Fischer and other cycle ; the InterzonaL The exact date and place for this event havc not yet leading contenders. -

Chess Basics

NEWSLETTER Library: Jan-2003 Morals of Chess Feb-2003 Humor in Chess Feb 15th SCC Guidelines March 2003 The History of Chess Notation by Robert John McCrary The number of books on chess is greater the number of books on all other games combined. Yet, chess books would be few and far between if there were not an efficient way to record the moves of games. Chess notation is thus the special written" language" of chess players, making it possible for a single book to contain hundreds of games by great players, or thousands of opening variations. Surprisingly, however, chess notation was slow to evolve. As late as the early nineteenth century, many chess books simply wrote out moves in full sentences! As a result, very few of those early games before the 1800's were recorded and preserved in print, and published analysis was correspondingly limited. In Shakespeare's day, for example, the standard English chess book gave the move 2.Qf3 as follows: " Then the black king for his second draught brings forth his queene, and placest her in the third house, in front of his bishop's pawne." Can we imagine recording a full 40-move game with each move written out like that! Nevertheless, the great 18th century player and author Andre Philidor, in his highly influential chess treatise published in 1747, continued to write out moves as full sentences. One move might read, "The bishop takes the bishop, checking." Or the move e5 would appear as "King's pawn to adverse 4th." Occasionally Philidor would abbreviate something, but generally he liked to spell everything out. -

Chess Pieces – Left to Right: King, Rook, Queen, Pawn, Knight and Bishop

CCHHEESSSS by Wikibooks contributors From Wikibooks, the open-content textbooks collection Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled "GNU Free Documentation License". Image licenses are listed in the section entitled "Image Credits." Principal authors: WarrenWilkinson (C) · Dysprosia (C) · Darvian (C) · Tm chk (C) · Bill Alexander (C) Cover: Chess pieces – left to right: king, rook, queen, pawn, knight and bishop. Photo taken by Alan Light. The current version of this Wikibook may be found at: http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Chess Contents Chapter 01: Playing the Game..............................................................................................................4 Chapter 02: Notating the Game..........................................................................................................14 Chapter 03: Tactics.............................................................................................................................19 Chapter 04: Strategy........................................................................................................................... 26 Chapter 05: Basic Openings............................................................................................................... 36 Chapter 06: -

Winawer First Edition 2019 by Thinkers Publishing Copyright © 2019 David Miedema

The Modernized French Defense Volume 1: Winawer First edition 2019 by Thinkers Publishing Copyright © 2019 David Miedema All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. All sales or enquiries should be directed to Thinkers Publishing, 9850 Landegem, Belgium. Email: [email protected] Website: www.thinkerspublishing.com Managing Editor: Romain Edouard Assistant Editor: Daniël Vanheirzeele Proofreading: Bernard Carpinter Software: Hub van de Laar Cover Design: Iwan Kerkhof Graphic Artist: Philippe Tonnard Back cover photo: Evert van de Worp and Aventus Production: BESTinGraphics ISBN: 9789492510495 D/2019/13730/2 The Modernized French Defense Volume 1: Winawer David Miedema Thinkers Publishing 2019 Key to Symbols ! a good move ⩲ White stands slightly better ? a weak move ⩱ Black stands slightly better !! an excellent move ± White has a serious advantage ?? a blunder ∓ Black has a serious advantage !? an interesting move +- White has a decisive advantage ?! a dubious move -+ Black has a decisive advantage □ only move → with an attack N novelty ↑ with an initiative ⟳ lead in development ⇆ with counterplay ⨀ zugzwang ∆ with the idea of = equality ⌓ better is ∞ unclear position ≤ worse is © with compensation for the + check sacrificed material # mate Bibliography John Watson, Play the French Viktor Moskalenko, The Wonderful