University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trades. [ Hampsbih~

1012 FOR TRADES. [ HAMPSBIH~. FORAGE MERCHANTS. Bennett C. 114 Fawcett rd. SoutLsea. Jerome H.J.:r3 Winchester st.AndoTer Ashdo wne & Co. Ltd. 72 St. George's Best Frederick James, 33 Millbank Johnson Harry, 46 Somers rd. Sthsea square, Port sea street, Southampton Kersey Arthur E. 7 Romsey road. Ray A. & F. 7:a & 73 East street; 24 Row Wil_liam, 107 Some'rs rd. Sthsea Shirlev, Southampton Bargate street; 21 Bernard street & B.Jwd!tch Fred, I58 Desborough rd. Kimber ·Frederick Alfred, 35 High 1t. Wood hill, Swaythling, Southampton Eastleigh Shirley, Southampton Rigler Waiter, Palmerston road, Bos Bradshaw Wm. 35 High st.Aldershot Kimber G. H. 98 Arnndel Rt.Landprt combe, Bournemouth & 305 Christ Bray George, 47 Cromwell road, Lawrence E.G. 70 Trinity st.Pareham church road, Pokesdown, Bourne Pokesdown, Bournemouth Layton Albt. 175 Albert rd.Southsea mouth. See advertisement Brown C.P. 15 Bonfire corner,Po'ttsea Leal Mrs. Lucy, I88 Wimborne road. Southern Counties Agricultural Trad Burley William, 96a, N ortham rd. 1Vinto11, Bournemouth ing Society Limited (The), Gran Southampton Lewis D. H. 35 Queen's rd. Aldershot worth road, Winchester Burridge C.E.55Hyde Park rd.Sthsea Lewis Thomas, Rumbridge street, Tinsley J. M. & Son, 48 High street, Burton Frederick, 86 Church road, Totton, Southampton • Chri-;tchurch & Sopley, Christ Landport & 77 Jessie rd. Southsea Linden Frederick, 93 Palmerston rd. church Camp hell William T. 77 St. Mary's Boscrunl•e, Bournemouth road, Southampton Lloyd Henry, 53 Chapel rd. Sthamptn FOREIGN :BANKERS. Cantwell H. 5o Railway view,Landprt Loader John, 29 Warblington 11treet, Carpenter Alfred, 9 Lake rd.Landprt Portsmouth Cook Thomas & Son, 32 Oxford st. -

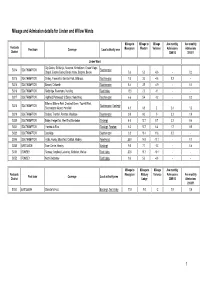

Mileage and Admissions

Mileage and Admission details for Linden and Willow Wards Mileage to Mileage to Mileage Ave monthly Ave monthly Postcode Post town Coverage Local authority area Moorgreen Western Variance Admissions Admissions District 2009/10 2010/11 Linden Ward City Centre, St. Mary's, Newtown, Nicholstown, Ocean Village, SO14 SOUTHAMPTON Southampton Chapel, Eastern Docks, Bevois Valley, Bargate, Bevois 5.6 5.0 -0.6 - 0.2 SO15 SOUTHAMPTON Shirley, Freemantle, Banister Park, Millbrook, Southampton 7.6 3.0 -4.6 0.2 - SO16 SOUTHAMPTON Bassett, Chilworth Southampton 8.4 3.5 -4.9 - 0.1 SO16 SOUTHAMPTON Redbridge, Rownhams, Nursling Test Valley 13.0 2.0 -11 - - SO17 SOUTHAMPTON Highfield, Portswood, St Denys, Swaythling Southampton 6.6 5.4 -1.2 - 0.2 Bitterne, Bitterne Park, Chartwell Green, Townhill Park, SO18 SOUTHAMPTON Southampton , Eastleigh Southampton Airport, Harefield 4.5 6.5 2 2.4 1.2 SO19 SOUTHAMPTON Sholing, Thornhill, Peartree, Woolston Southampton 9.0 9.0 0 3.2 1.9 SO30 SOUTHAMPTON Botley, Hedge End, West End, Bursledon Eastleigh 4.0 12.7 8.7 2.2 0.4 SO31 SOUTHAMPTON Hamble-le-Rice Eastleigh , Fareham 6.3 12.7 6.4 1.7 0.5 SO32 SOUTHAMPTON Curdridge Southampton 3.8 15.4 11.6 0.2 - SO45 SOUTHAMPTON Hythe, Fawley, Blackfield, Calshot, Hardley New Forest 25.9 14.8 -11.1 - 0.1 SO50 EASTLEIGH Town Centre, Hamley Eastleigh 9.0 7.7 -1.3 - 0.6 SO51 ROMSEY Romsey, Ampfield, Lockerley, Mottisfont, Wellow Test Valley 20.8 10.7 -10.1 - - SO52 ROMSEY North Baddesley Test Valley 9.6 5.0 -4.6 - - Mileage to Mileage to Mileage Ave monthly Postcode Moorgreen Melbury Variance Admissions Ave monthly Post town Coverage Local authority area District Lodge 2009/10 Admissions 2010/11 SO53 EASTLEIGH Chandler's Ford Eastleigh , Test Valley 11.0 9.0 -2 1.8 0.6 1 Mileage to Mileage to Mileage Ave monthly Ave monthly Postcode Post town Coverage Local authority area Moorgreen Western Variance Admissions Admissions District 2009/10 2010/11 Willow Ward City Centre, St. -

Policing Southampton Partnership Briefing

Policing Southampton Partnership briefing September 2019 Southampton is a vibrant, busy city that we are all proud to protect and serve. This newsletter is for our trusted partners with the aim to bring you closer to the teams and the people that identify risk, tackle offenders and protect those who most need our help. We will list the challenges we are facing, the problems we are solving, and opportunities to work together. Operation Sceptre We took part in Operation Sceptre which was a national week of action that ran from September 16 to 22. In Southampton we demonstrated our commitment through several engagement events, proactive patrols, visits to parents of young people thought be carrying knives, and we conducted knife sweeps. In Shirley, a PCSO hosted a live, two hours engagement session on Twitter and the team carried out a test purchase operation in four retail outlets. All shops passed which is great news. Through our focus on high harm, we stopped and searched a man who was in possession of an axe and he was charged. We also ar- rested a man after he was reported to be making threats towards his ex partner with a knife. Most notably, a man was reported to have committed three knife point robberies in the centre of Southampton, he was quickly arrested, charged and remanded. For us to be able try and influence young people and prevent the next generation from carrying knives, we produced a campaign via the Police Apprentice Scheme in partnership with schools and the Saints Foundation and asked children come up with an idea that they thought would make their peers aged 9 to 14 think twice about choosing to carry a knife. -

Neighbourhoods in England Rated E for Green Space, Friends of The

Neighbourhoods in England rated E for Green Space, Friends of the Earth, September 2020 Neighbourhood_Name Local_authority Marsh Barn & Widewater Adur Wick & Toddington Arun Littlehampton West and River Arun Bognor Regis Central Arun Kirkby Central Ashfield Washford & Stanhope Ashford Becontree Heath Barking and Dagenham Becontree West Barking and Dagenham Barking Central Barking and Dagenham Goresbrook & Scrattons Farm Barking and Dagenham Creekmouth & Barking Riverside Barking and Dagenham Gascoigne Estate & Roding Riverside Barking and Dagenham Becontree North Barking and Dagenham New Barnet West Barnet Woodside Park Barnet Edgware Central Barnet North Finchley Barnet Colney Hatch Barnet Grahame Park Barnet East Finchley Barnet Colindale Barnet Hendon Central Barnet Golders Green North Barnet Brent Cross & Staples Corner Barnet Cudworth Village Barnsley Abbotsmead & Salthouse Barrow-in-Furness Barrow Central Barrow-in-Furness Basildon Central & Pipps Hill Basildon Laindon Central Basildon Eversley Basildon Barstable Basildon Popley Basingstoke and Deane Winklebury & Rooksdown Basingstoke and Deane Oldfield Park West Bath and North East Somerset Odd Down Bath and North East Somerset Harpur Bedford Castle & Kingsway Bedford Queens Park Bedford Kempston West & South Bedford South Thamesmead Bexley Belvedere & Lessness Heath Bexley Erith East Bexley Lesnes Abbey Bexley Slade Green & Crayford Marshes Bexley Lesney Farm & Colyers East Bexley Old Oscott Birmingham Perry Beeches East Birmingham Castle Vale Birmingham Birchfield East Birmingham -

2014 Air Quality Progress Report and Detailed Assessment for Southampton City Council

2014 Air Quality Progress Report and Detailed Assessment for Southampton City Council In fulfillment of Part IV of the Environment Act 1995 Local Air Quality Management May 2015 Southampton City Council LAQM Progress Report 2013 1 Southampton City Council Local Authority Southampton City Council Officer Department Regulatory Services Address Civic Centre, Southampton Telephone 023 80917531 e-mail [email protected] Report Reference PR5 number Date May 2015 LAQM Progress Report 2013 2 Southampton City Council Executive Summary Southampton City Council has examined the results from 2013 monitoring in the Southampton Unitary Authority Area. Concentrations within most of the AQMAs still exceed the 40 µg/m3 annual mean standard for nitrogen dioxide at some relevant receptors and the AQMAs should remain. This Progress Report incorporates detailed assessments for four areas, Portswood Road; the southern section of Romsey Road, 2 residential receptors within the docks and Queens Terrace/Orchard Place. The detailed assessments have used NOx tube monitoring and appended at the end of the report as appendix B, C, D and E. This report recommends that the existing AQMA on Romsey Road is extended to include the NOx tube locations that are exceeding the 40 µg/m3 annual mean standard for nitrogen dioxide at the southern section, the junction with Shirley Road. The existing Bevois Valley AQMA should be extended to include the NOx tube locations that are exceeding the 40 µg/m3 annual mean standard for nitrogen dioxide on Portswood Road to the north. The monitoring in the docks at the residential receptors shows that this location is very unlikely to exceed the 40 µg/m3 annual mean standard for nitrogen dioxide, and no further action is required. -

1997 Sundance Film Festival Awards Jurors

1997 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL The 1997 Sundance Film Festival continued to attract crowds, international attention and an appreciative group of alumni fi lmmakers. Many of the Premiere fi lmmakers were returning directors (Errol Morris, Tom DiCillo, Victor Nunez, Gregg Araki, Kevin Smith), whose earlier, sometimes unknown, work had received a warm reception at Sundance. The Piper-Heidsieck tribute to independent vision went to actor/director Tim Robbins, and a major retrospective of the works of German New-Wave giant Rainer Werner Fassbinder was staged, with many of his original actors fl own in for forums. It was a fi tting tribute to both Fassbinder and the Festival and the ways that American independent cinema was indeed becoming international. AWARDS GRAND JURY PRIZE JURY PRIZE IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Documentary—GIRLS LIKE US, directed by Jane C. Wagner and LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY (O SERTÃO DAS MEMÓRIAS), directed by José Araújo Tina DiFeliciantonio SPECIAL JURY AWARD IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Dramatic—SUNDAY, directed by Jonathan Nossiter DEEP CRIMSON, directed by Arturo Ripstein AUDIENCE AWARD JURY PRIZE IN SHORT FILMMAKING Documentary—Paul Monette: THE BRINK OF SUMMER’S END, directed by MAN ABOUT TOWN, directed by Kris Isacsson Monte Bramer Dramatic—HURRICANE, directed by Morgan J. Freeman; and LOVE JONES, HONORABLE MENTIONS IN SHORT FILMMAKING directed by Theodore Witcher (shared) BIRDHOUSE, directed by Richard C. Zimmerman; and SYPHON-GUN, directed by KC Amos FILMMAKERS TROPHY Documentary—LICENSED TO KILL, directed by Arthur Dong Dramatic—IN THE COMPANY OF MEN, directed by Neil LaBute DIRECTING AWARD Documentary—ARTHUR DONG, director of Licensed To Kill Dramatic—MORGAN J. -

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

ITEM NO: C2a APPENDIX 1

ITEM NO: C2a APPENDIX 1 Background Information Approximately 3600 flats and houses were built in Southampton in the five year period up to March 2006. About 80% of these were flats. Some 25% of these flats and houses were in the city centre, where the on-street parking facilities are available to everyone on a "Pay and Display" basis. Outside the central area, only about 10% of the city falls within residents' parking zones. So, out of the 3600 properties in all, it is estimated that only about 270 (or 7.5%) will have been within residents' parking zones and affected by the policy outlined in the report. Only in a few (probably less than 20) of these cases have difficulties come to light. In general, there is no question of anyone losing the right to a permit, although officers are currently seeking to resolve a situation at one particular development where permits have been issued in error. There are currently 13 schemes funded by the City Council and these cover the following areas:- Polygon Area Woolston North Woolston South Newtown/Nicholstown Bevois Town Freemantle Coxford (General Hospital) Shirley University Area (5 zones) These schemes operate from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. on weekdays and, in some cases, at other times as well. In addition, there are three further schemes at Bitterne Manor, Itchen and Northam that only operate during football matches or other major events at St Mary’s Stadium. These are funded by Southampton Football Club. Within all these schemes, parking bays are marked on the road for permit holders, often allowing short-stay parking by other users as well. -

Primary Care Networks for Southampton City CCG July 2019

Primary Care Networks for Southampton City CCG July 2019 WEST PCN Clinical Director(s) : Dr Dan Tongue Dr Sanjeet Kumar Lordshill Aldermoor Practice Raw Pop @ Weighted Practice Name Code Jan 19 Pop (GSUM) WEST J82002 LORDSHILL HEALTH CENTRE 11,540 11,357 J82022 VICTOR STREET SURGERY 12,308 12,168 Adelaide J82062 SHIRLEY AVENUE AND CHEVIOT ROAD PRACTICE 15,515 14,615 Victor St J82088 THE GROVE MEDICAL PRACTICE 14,560 13,494 Brook House Cheviot Rd Shirley Ave J82092 ALDERMOOR SURGERY 8,179 7,758 Raymond Rd J82115 ATHERLEY HOUSE SURGERY 5,211 4,713 Shirley Health Partnership J82126 DR S ROBINSON AND PARTNERS 4,516 4,604 J82207 HILL LANE SURGERY 9,337 8,687 J82213 BROOK HOUSE SURGERY 5,545 5,184 86,711 82,580 Plus circa 5k patients from Solent Adelaide – Solent as associate member of PCN Locality geographic boundary PCN absolute boundary NORTH PCN Clinical Director : Dr Vikas Shetty Dr Matt Prendergast Stoneham La Burgess Rd University HC Highfield Practice Raw Pop @ Weighted Practice Name Code Jan 19 Pop (GSUM) J82001 BURGESS ROAD SURGERY 9,503 7,662 J82080 UNIVERSITY HEALTH SERVICE SOUTHAMPTON 19,037 12,798 J82087 STONEHAM LANE SURGERY 7,124 6,845 J82663 HIGHFIELD HEALTH 6,675 5,058 42,339 32,363 Locality geographic boundary PCN absolute boundary CENTRAL PCN Clinical Director : Dr Fraser Malloch Mulberry St Denys (Br) Portswood (Br) Alma Rd Practice Raw Pop @ Weighted Practice Name Homeless HC Code Jan 19 Pop (GSUM) Nicholstown J82081 ST MARY'S SURGERY - SOUTHAMPTON 24,249 21,410 J82122 DR ORD-HUME AND PARTNERS 9,746 10,335 J82183 MULBERRY -

Introduction: Shakespeare, Spectro-Textuality, Spectro-Mediality 1

Notes Introduction: Shakespeare, Spectro-Textuality, Spectro-Mediality 1 . “Inhabiting,” as distinct from “residing,” suggests haunting; it is an uncanny form of “residing.” See also, for instance, Derrida’s musings about the verb “to inhabit” in Monolingualism (58). For reflections on this, see especially chapter 4 in this book. 2 . Questions of survival are of course central to Derrida’s work. Derrida’s “classical” formulation of the relationship between the living-on of a text and (un)translat- ability is in Parages (147–48). See also “Des Tours” on “the necessary and impos- sible task of translation” (171) and its relation with the surviving dimension of the work (182), a reading of Walter Benjamin’s “The Task of the Translator.” In one of his posthumously published seminars, he stresses that survival—or, as he prefers to call it, “survivance”—is “neither life nor death pure and simple,” and that it is “not thinkable on the basis of the opposition between life and death” (Beast II 130). “Survivance” is a trace structure of iterability, a “living dead machine” (131). To Derrida, what is commonly called “human life” may be seen as one of the outputs of this structure that exceeds the “human.” For a cogent “posthumanist” understanding of Derrida’s work, and the notion of the trace in particular, see Wolfe. 3 . There are of course significant exceptions, and this book is indebted to these studies. Examples are Wilson; Lehmann, Shakespeare Remains ; Joughin, “Shakespeare’s Genius” and “Philosophical Shakespeares”; and Fernie, “Introduction.” Richard Burt’s work is often informed by Derrida’s writings. -

GREEN NEWS Portswood

GREEN NEWS Katherine Barbour Local Green Party Portswood Candidate WORKING HARD ALL YEAR ROUND Did you know that cycling exposes us to the least pollution on our commute? It is also the best for our health so a WIN- WIN Jack’s Story The recent decision to not implement Die-In at the Bargate a Clean Air Zone is bad news for No Clean Air Zone – people like Jack in Bitterne. He has Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary shame on our City Disease (COPD) and struggles to Southampton City Council were breathe when he comes into the city. proposing to create a clean air zone, The air quality in parts of the city is charging lorries, buses and taxis to getting worse and little is being done enter the city. This proposal is to address this. Jack says, “you can’t expected to be thrown out by the see it, you are breathing it all the Labour council. This means we will time” continue breathing polluted air. To The Green Party has a set of policies highlight this many people to tackle this; stopping airport demonstrated at the Bargate on expansion, ensuring cruise liners plug Saturday 12th January – this was in in, expanding bus routes and memory of the 110 people who die building safe cycle routes in the city prematurely from poor air each year in our city –many more struggle every day with breathing difficulties. I believe SCC should reconsider implementing a clean air zone – 56% of respondents to the clean air consultation were in favour - and not buckle under the pressure from businesses and politicians. -

1 Shakespeare and Film

Shakespeare and Film: A Bibliographic Index (from Film to Book) Jordi Sala-Lleal University of Girona [email protected] Research into film adaptation has increased very considerably over recent decades, a development that coincides with postmodern interest in cultural cross-overs, artistic hybrids or heterogeneous discourses about our world. Film adaptation of Shakespearian drama is at the forefront of this research: there are numerous general works and partial studies on the cinema that have grown out of the works of William Shakespeare. Many of these are very valuable and of great interest and, in effect, form a body of work that is hybrid and heterogeneous. It seems important, therefore, to be able to consult a detailed and extensive bibliography in this field, and this is the contribution that we offer here. This work aims to be of help to all researchers into Shakespearian film by providing a useful tool for ordering and clarifying the field. It is in the form of an index that relates the bibliographic items with the films of the Shakespearian corpus, going from the film to each of the citations and works that study it. Researchers in this field should find this of particular use since they will be able to see immediately where to find information on every one of the films relating to Shakespeare. Though this is the most important aspect, this work can be of use in other ways since it includes an ordered list of the most important contributions to research on the subject, and a second, extensive, list of films related to Shakespeare in order of their links to the various works of the canon.