Agency at the Frontier and the Building of Territoriality in the Naranjo-Ceibo Corridor, Peten, Guatemala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout

English by Alain Stout For the Textile Industry Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout Compiled and created by: Alain Stout in 2015 Official E-Book: 10-3-3016 Website: www.TakodaBrand.com Social Media: @TakodaBrand Location: Rotterdam, Holland Sources: www.wikipedia.com www.sensiseeds.nl Translated by: Microsoft Translator via http://www.bing.com/translator Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout Table of Contents For Word .............................................................................................................................. 5 Textile in General ................................................................................................................. 7 Manufacture ....................................................................................................................... 8 History ................................................................................................................................ 9 Raw materials .................................................................................................................... 9 Techniques ......................................................................................................................... 9 Applications ...................................................................................................................... 10 Textile trade in Netherlands and Belgium .................................................................... 11 Textile industry ................................................................................................................... -

Shuttle-Craft Guild Bulletin #7, April 1925

Shuttle-Craft Guild Bulletin #7, April 1925 This Bulletin’s weave structure, the Bronson Book calls it barleycorn and has many 4 shaft drafts weave was first introduced last month as one of the in Chapter 10 (pages 83-92). Davison writes that the recommended structures for baby blankets. The weave is ideal for linens and specifically, calls out Shuttle Craft Bulletin #7 article gets into more detail. the Mildred Keyser Linen weave for toweling (page Mary called this structure the Bronson weave as 86). It is also known as droppdräll in Sweden and she originally found it in the book, Domestic diaper by the Mary’s original source (Bronson 1817). Manufacturer’s Assistant and Family Directory in the A diaper pattern weave refers to a small repeating Arts of Weaving and Dyeing, by J Bronson and R. overall pattern. Bronson, printed 1817. She stated that the weave Anne Dixon’s book The Handweaver’s Pattern appeared nowhere else as far as she knows. The Directory includes several examples of 4-shaft Spot Bronson book is available as a Dover publication, as Bronson. Dixon states that this weave produces a an e book or in paperback (at some very reasonable delicate textured cloth. Her examples of most of them prices –see this link: amazon.com/Early-American- are shown in two light colors-see the draft below. Weaving-Dyeing-Americana/dp/0486234401). The Bronson weave is commonly woven in one color The Bronson weave is a spot weave from England for both warp and weft, although Mary Atwater and was used for linens and for shawls, but in states that a second color may be added in the weft Colonial America, it was used for linens exclusively. -

Recollections and Notes, Vol. 1 (1887–1945) Translated by Abe

Vita Mathematica 18 Hugo Steinhaus Mathematician for All Seasons Recollections and Notes, Vol. 1 (1887–1945) Translated by Abe Shenitzer Edited by Robert G. Burns, Irena Szymaniec and Aleksander Weron Vita Mathematica Volume 18 Edited by Martin MattmullerR More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/4834 Hugo Steinhaus Mathematician for All Seasons Recollections and Notes, Vol. 1 (1887–1945) Translated by Abe Shenitzer Edited by Robert G. Burns, Irena Szymaniec and Aleksander Weron Author Hugo Steinhaus (1887–1972) Translator Abe Shenitzer Brookline, MA, USA Editors Robert G. Burns York University Dept. Mathematics & Statistics Toronto, ON, Canada Irena Szymaniec Wrocław, Poland Aleksander Weron The Hugo Steinhaus Center Wrocław University of Technology Wrocław, Poland Vita Mathematica ISBN 978-3-319-21983-7 ISBN 978-3-319-21984-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-21984-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015954183 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

Historic Costuming Presented by Jill Harrison

Historic Southern Indiana Interpretation Workshop, March 2-4, 1998 Historic Costuming Presented By Jill Harrison IMPRESSIONS Each of us makes an impression before ever saying a word. We size up visitors all the time, anticipating behavior from their age, clothing, and demeanor. What do they think of interpreters, disguised as we are in the threads of another time? While stressing the importance of historically accurate costuming (outfits) and accoutrements for first- person interpreters, there are many reasons compromises are made - perhaps a tight budget or lack of skilled construction personnel. Items such as shoes and eyeglasses are usually a sticking point when assembling a truly accurate outfit. It has been suggested that when visitors spot inaccurate details, interpreter credibility is downgraded and visitors launch into a frame of mind to find other inaccuracies. This may be true of visitors who are historical reenactors, buffs, or other interpreters. Most visitors, though, lack the heightened awareness to recognize the difference between authentic period detailing and the less-than-perfect substitutions. But everyone will notice a wristwatch, sunglasses, or tennis shoes. We have a responsibility to the public not to misrepresent the past; otherwise we are not preserving history but instead creating our own fiction and calling it the truth. Realistically, the appearance of the interpreter, our information base, our techniques, and our environment all affect the first-person experience. Historically accurate costuming perfection is laudable and reinforces academic credence. The minute details can be a springboard to important educational concepts; but the outfit is not the linchpin on which successful interpretation hangs. -

Dragon's Blood Profile • Norman Farnsworth Tribute • History Of

HerbalGram 92 • November 2011 – January 2012 History of Adulterants • Norman Farnsworth Tribute • Dragon's Blood Profile • Medicinal Plant Fabrics • Soy Reduces Blood Pressure Reduces • Soy Fabrics • Medicinal Plant Blood Profile • Dragon's Tribute 2011 – January HerbalGram 92 • November 2012 History • Norman Farnsworth of Adulterants Dragon's Blood Profile • Norman Farnsworth Tribute • History of Adulterants • Cannabis Genome Medical Plant Fabric Dyeing • Soy Reduces Blood Pressure • Cocoa and Heart Disease The Journal of the American Botanical Council Number 92 | November 2011 – January 2012 US/CAN $6.95 www.herbalgram.org www.herbalgram.org www.herbalgram.org 2011 HerbalGram 92 | 1 Herb Pharm’s Botanical Education Garden PRESERVING THE INTEGRITY OF NATURE'S CHEMISTRY The Art & Science of Herbal Extraction At Herb Pharm we continue to revere and follow the centuries-old, time-proven wisdom of traditional herbal medicine, but we also integrate that wisdom with the herbal sciences and technology of the 21st Century. We produce our herbal extracts in our new, FDA-audited, GMP- compliant herb processing facility which is located just two miles from our certified-organic herb farm. This assures prompt delivery of HPTLC chromatograph show- freshly-harvested herbs directly from the fields, or recently dried herbs ing biochemical consistency of 6 directly from the farm’s drying loft. Here we also receive other organic batches of St. John’s Wort extracts and wildcrafted herbs from various parts of the USA and world. In producing our herbal extracts we use precision scientific instru- ments to analyze each herb’s many chemical compounds. However, You’ll find Herb Pharm we do not focus entirely on the herb’s so-called “active compound(s)” at most health food stores and, instead, treat each herb and its chemical compounds as an integrated whole. -

Smart Border Management an Indian Perspective September 2016

Content Smart border management p4 / Responding to border management challenges p7 / Challenges p18 / Way forward: Smart border management p22 / Case studies p30 Smart border management An Indian perspective September 2016 www.pwc.in Foreword India’s geostrategic location, its relatively sound economic position vis-à-vis its neighbours and its liberal democratic credentials have induced the government to undertake proper management of Indian borders, which is vital to national security. In Central and South Asia, smart border management has a critical role to play. When combined with liberal trade regimes and business-friendly environments, HIğFLHQWFXVWRPVDQGERUGHUFRQWUROVFDQVLJQLğFDQWO\LPSURYHSURVSHFWVIRUWUDGH and economic growth. India shares 15,106.7 km of its boundary with seven nations—Pakistan, China, Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar, Bangladesh and Afghanistan. These land borders run through different terrains; managing a diverse land border is a complex task but YHU\VLJQLğFDQWIURPWKHYLHZRIQDWLRQDOVHFXULW\,QDGGLWLRQ,QGLDKDVDFRDVWDO boundary of 7,516.6 km, which includes 5,422.6 km of coastline in the mainland and 2,094 km of coastline bordering islands. The coastline touches 9 states and 2 union territories. The traditional approach to border management, i.e. focussing only on border security, has become inadequate. India needs to not only ensure seamlessness in the legitimate movement of people and goods across its borders but also undertake UHIRUPVWRFXUELOOHJDOĠRZ,QFUHDVHGELODWHUDODQGPXOWLODWHUDOFRRSHUDWLRQFRXSOHG with the adoption of -

Texas Administrative Code Title 40. Social Services and Assistance Part 19. Department of Family and Protective Services Chapter 746

Texas Administrative Code _Title 40. Social Services and Assistance _Part 19. Department of Family and Protective Services _Chapter 746. Minimum Standards for Child-Care Centers _Subchapter H. Basic Care Requirements for Infants 40 TAC § 746.2401 Tex. Admin. Code tit. 40, § 746.2401 § 746.2401. What are the basic care requirements for infants? Basic care for infants must include: (1) Care by the same caregiver on a regular basis, when possible; (2) Individual attention given to each child including playing, talking, cuddling, and holding; (3) Holding and comforting a child who is upset; (4) Prompt attention given to physical needs, such as feeding and diapering; (5) Talking to children as they are fed, changed, and held, such as naming objects, singing, or saying rhymes; (6) Ensuring the environment is free of objects that may cause choking in children younger than three years; and (7) Never leaving an infant unsupervised. 40 TAC § 746.2403 Tex. Admin. Code tit. 40, § 746.2403 § 746.2403. How must I arrange the infant care area? The room arrangement of the infant care area must: (1) Make it possible for caregivers to see and/or hear all children at a glance and be able to intervene when necessary; Current through 39 Tex.Reg. No. 5000, dated June 27, 2014, as effective on or before June 30, 2014 Texas Administrative Code _Title 40. Social Services and Assistance _Part 19. Department of Family and Protective Services _Chapter 746. Minimum Standards for Child-Care Centers _Subchapter H. Basic Care Requirements for Infants (2) Include safe, open floor space for floor time play; (3) Separate infants from children more than 18 months older than the youngest child in the group, except when 12 or fewer children are in care; (4) Have cribs far enough apart so that one infant may not reach into another crib; (5) Provide caregivers with enough space to walk and work between cribs, cots, and mats; and (6) Ensure older children do not use the infant area as a passageway to other areas of the building. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles the Ground Plan As a Tool

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Ground Plan as a Tool for The Identification and Study of Houses in an Old Kingdom Special-Purpose Settlement at Heit el-Ghurab, Giza A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures by Mohsen E Kamel 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Ground Plan as a Tool for The Identification and Study of Houses in an Old Kingdom Special-Purpose Settlement at Heit el-Ghurab, Giza by Mohsen E Kamel Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Willemina Z. Wendrich, Chair The ground plan is an essential goal of the settlement archaeologist. For the archaeologist who would attempt to glean evidence of settlements of the Old Kingdom (c. 2543 - 2120 BCE), the ground plan is most often the ultimate goal, for although the seemingly eternal stone funerary monuments of Giza dominate the Old Kingdom landscape (both literally and figuratively), the Pyramid Age has not left standing the mudbrick walls of the houses within which people lived-- the preponderance of Old-Kingdom wall remnants comprising mere centimeters. Without an accurate ground plan, material culture and faunal and botanical evidence have no context. This study presents a detailed, concrete analysis and comparison of the ground plans of two structures that can be interpreted as houses from the Old Kingdom, 4th-dynasty (2543 – 2436 BCE) settlement site of Heit el-Ghurab at Giza. The houses whose ground plans are presented here are representative of a corpus of unpublished probable dwellings from this site, which excavation ii suggests was a “special-purpose” settlement that housed and provisioned the personnel engaged in the monumental constructions on the Giza plateau. -

School Building in Long Branch

Weather **f MLY nUd tomorrew, Ugh Red Bank Area f to upper «% Outlook Friday, "V Copyiiiit-tto Red Bank Register, lac, MS, fair tad coatlaued mm. MONMOUTH COUNTY'S HOME NEWSPAPER FOR 87 YEARS DIAL 741-0010 . 178 WEDNESDAY, MARCH 9, 1966 7c PER COPY PAGE ONE 650 Junior High Students Evacuated in Fire School Building in Long Branch LONG BRANCH — Fire officials were scheduled to begin • burn throughout the rest of the afternoon, but was confined fire hoses to prevent blowing sparks from igniting them. Elec- hurst, Wanamaasa, Deal and Alfenhurst fought tfie blaze. The their probe this morning into the cause of the fire which yester- within the gutted 67-year-old structure. tricity was cut off shortly after the blaze began, and the Wanamassa company used its newly acquired snorkel fire day destroyed the Chattle School Building and forced the evac- Firemen were recalled to the scene last night at 6:4$ and Willow Ave. houses were without electric power for most of truck, which carried the aerial rig from the Allenhurst.com* uation of some 65Q junior high school students. - 9:45 to extinguish flames which broke out. the afternoon. 1 • '•"••" •>'.•••••'•*• party. The-city used its two aerial trucks. The investigation was delayed because four feet of water BUILDINGS EVACUATED Chief Richter said the*fire quickly spread through the air tilled the basement area where the fire was believed to have ' School children and teachers were evacuated from the duct system of the buildings the' flames being carried' almost T^ie fire, was discovered by School Principal James J. -

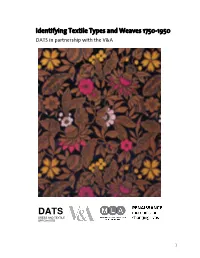

Identifying Textile Types and Weaves 1750-1950 DATS in Partnership with the V&A

Identifying Textile Types and Weaves 1750-1950 DATS in partnership with the V&A DATS DRESS AND TEXTILE SPECIALISTS 1 Identifying Textile Types and Weaves 1750-1950 Text copyright © DATS, 2007 Image copyrights as specified in each section. This information pack has been produced to accompany a one-day workshop of the same name taught by Sue Kerry and held at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery Collections Centre on 29th November 2007. The workshop is one of three produced in collaboration between DATS and the V&A, funded by the Renaissance Subject Specialist Network Implementation Grant Programme, administered by the MLA. The purpose of the workshops is to enable participants to improve the documentation and interpretation of collections and make them accessible to the widest audience. Participants will have the chance to study objects at first hand to help increase their confidence in identifying textile materials and techniques. This information pack is intended as a means of sharing the knowledge communicated in the workshops with colleagues and the public. Other workshops / information packs in the series: Identifying Printed Textiles in Dress 1740 -1890 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Front Cover - English silk tissue, 1875, Spitalfields. T.147-1972 , Image © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum 2 Identifying Textile Types and Weaves Contents Page 2. List of Illustrations 1 3. Introduction and identification checklist 3 4. Identifying Textile Types - Fibres and Yarns 4 5. Weaving and Woven Cloth Historical Framework - Looms 8 6. Identifying Basic Weave Structures – Plain Cloths 12 7. Identifying Basic Weave Structures – Figured / Ornate Cloths 17 8. -

Diaper Changing Pad Carol A

Diaper Changing Pad Carol A. Brown When you are away from home with baby, it’s nice to have a clean surface for diaper changes. Take this pad with you and you’ll always be prepared. The changing pad is 15 1/4” wide x 30 1/2” long when open; when folded into thirds it is 9” x 15 1/4” x 3/4” thick. It also has a flap with a Velcro ® closure. (See the additional in- structions for an alternate way to finish the flap, including adding embroidery.) For best results, wipe the vinyl surface clean or, if you prefer, wash the changing pad by hand and air dry. Do not wring the vinyl. Materials: 1. Thick fusible fleece for pad: three pieces, each 14” x 8 1/2”. (Fig. 1) 2. Brightly colored calico print for pad: three pieces, each 15” x 9 1/2”. The pieces need not all be the same fabric. You can use three different ones, or one striped fabric, with a middle piece turned sideways for fun. (Polyurethane coated fabric will allow you to omit the vinyl.) (Fig. 2) 3. Mid-weight clear or frosted vinyl for pad: three pieces, each 15” x 9 1/2”. (Fig. 3) 4. Denim or sturdy fabric for shell: 36” x 17”. (The denim I used was overdyed with stripes on the wrong side. The stripes will not show on the finished pad but help show right and wrong sides of the fabric in my pictures.) (Fig. 4) 5. Embroidery design up to 240 mm wide and 150 mm high. -

Diaper Design for Polyester Fabric

Research Article Journal of Volume 10:3, 2020 DOI: 10.37421/jtese.2020.10.408 Textile Science & Engineering ISSN: 2165-8064 Open Access Diaper Design for Polyester Fabric Onuegbu GC, Nnorom OO, Okonkwo Samuel Nonso* and Ojiaku PC Department of Polymer and Textile Engineering, Federal University of Technology Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria Abstract Knowledge about the indigenous traditional woven fabrics of Nigeria reveals the extent the people have advanced in the area of weaving and clothing need. Unfortunately, the indigenous weaving culture faces threat of extinction due to the introduction of machine made fabrics. Here, double twisted and single twisted polyester yarn was used as warp and weft respectively to weave a diaper design for polyester fabric which was used for interior decoration. The diaper weave was produced using a four-shaft hand loom and the steps involved were warping, beaming, heddling or drafting, reeding/denting, tie-up/gaiting, shedding, picking and beating up. The woven diaper polyester was cut and sewn for interior decoration. The diaper twill weave design produced has a front and a back side and was found to be durable, attractive and reliable. Soiling and stains were less noticeable on the uneven surface of the diaper designed twill weave than on a smooth surface, such as plain weaves and as a result makes them suitable for sturdy work clothing, draperies/curtains, durable upholsteries and furnishings. The fewer interlacing in this design as compared to other weaves allow the yarns to move more freely, and therefore they are softer and more pliable, and drape better than most plain-weave textiles.