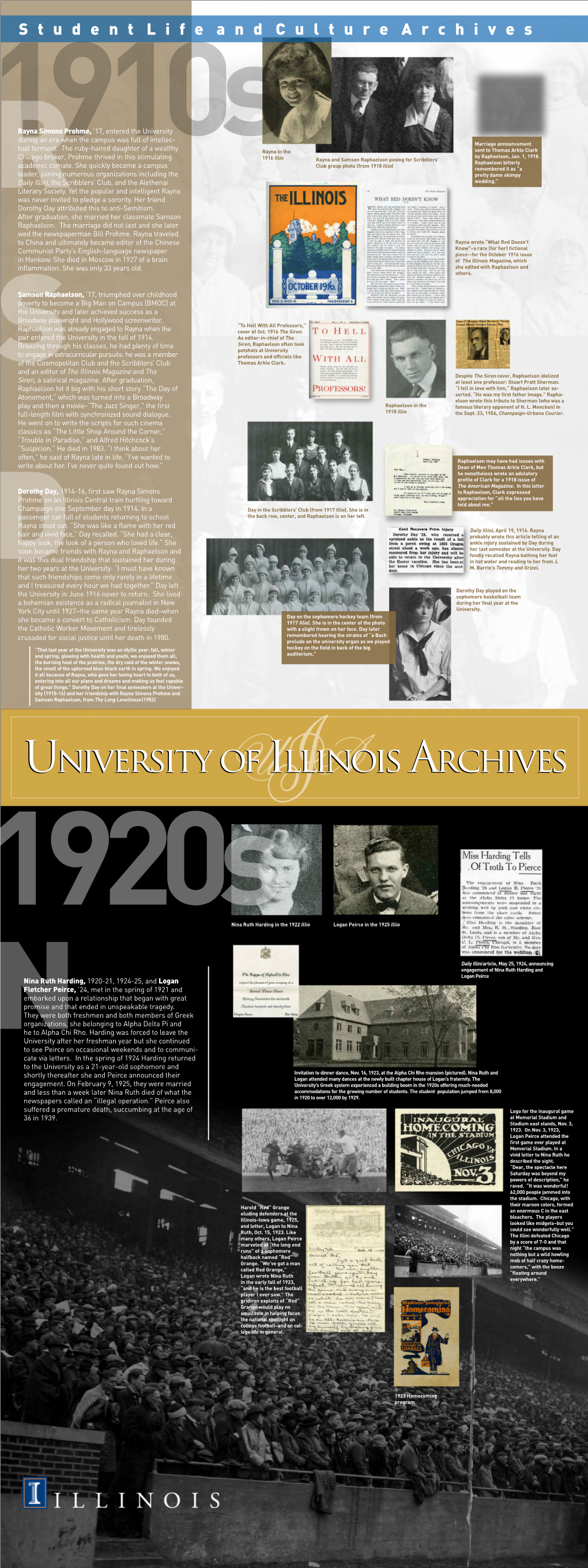

S T U D E N T L I F E a N D C U L T U R E a R C H I V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modern Jewish Culture: Key Texts and Their Afterlives

Modern Jewish Culture: Key Texts and Their Afterlives Comparative Literature 01:195:230 Jewish Studies 01:563:230 Provisional Syllabus Prof. Jeffrey Shandler Office: Room 102 Email: [email protected] Miller Hall (14 College Ave.; behind 12 College Ave.) Tel: 848-932-1709 Course Description This course examines four key texts, written between 1894 and 1944: Sholem Aleichem’s “Tevye the Dairyman” stories (the basis of the Broadway musical Fiddler on the Roof), Sh. Ansky’s play “The Dybbuk,” Samson Raphaelson’s short story “The Day of Atonement” (the basis of the 1927 film The Jazz Singer), and Anne Frank’s Diary of a Young Girl. These works have become fixtures not only of modern Jewish culture but also of world culture, primarily through adaptations and remediations in stage, film, broadcasting, music, dance, and visual art. Students will read these four texts, discuss the complex histories of their original composition, and examine the trajectories defined by how these works have been revisited over the years in diverse forms by various communities. As a result, students will consider how the texts in question have become modern cultural touchstones and how to understand the acts of adaptation and remediation as cultural practices in their own right. No prerequisites. All readings in English. Core Learning Goal AHp. Analyze arts and/or literatures in themselves and in relation to specific histories, values, languages, cultures, and technologies. Course Learning Goals Students will: • Examine the creative processes behind key works of modern Jewish culture, focusing on issues of composition, redaction, and translation. • Examine the process by which these key works are adapted, remediated, or otherwise responded to in various media and genre, focusing on these efforts as cultural practices in their own right. -

Appendix 5 Selected Films in English of Operettas by Composers for the German Stage

Appendix 5 Selected Films in English of Operettas by Composers for the German Stage The Merry Widow (Lehár) 1925 Mae Murray & John Gilbert, dir. Erich von Stroheim. Metro- Goldwyn-Mayer. 137 mins. [Silent] 1934 Maurice Chevalier & Jeanette MacDonald, dir. Ernst Lubitsch. MGM. 99 mins. 1952 Lana Turner & Fernando Lamas, dir. Curtis Bernhardt. Turner dubbed by Trudy Erwin. New lyrics by Paul Francis Webster. MGM. 105 mins. The Chocolate Soldier (Straus) 1914 Alice Yorke & Tom Richards, dir. Walter Morton & Hugh Stanislaus Stange. Daisy Feature Film Company [USA]. 50 mins. [Silent] 1941 Nelson Eddy, Risë Stevens & Nigel Bruce, dir. Roy del Ruth. Music adapted by Bronislau Kaper and Herbert Stothart, add. music and lyrics: Gus Kahn and Bronislau Kaper. Screenplay Leonard Lee and Keith Winter based on Ferenc Mulinár’s The Guardsman. MGM. 102 mins. 1955 Risë Stevens & Eddie Albert, dir. Max Liebman. Music adapted by Clay Warnick & Mel Pahl, and arr. Irwin Kostal, add. lyrics: Carolyn Leigh. NBC. 77 mins. The Count of Luxembourg (Lehár) 1926 George Walsh & Helen Lee Worthing, dir. Arthur Gregor. Chadwick Pictures. [Silent] 341 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.33.14, on 01 Oct 2021 at 07:31:57, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306 342 Appendix 5 Selected Films in English of Operettas Madame Pompadour (Fall) 1927 Dorothy Gish, Antonio Moreno & Nelson Keys, dir. Herbert Wilcox. British National Films. 70 mins. [Silent] Golden Dawn (Kálmán) 1930 Walter Woolf King & Vivienne Segal, dir. Ray Enright. -

Nashville Community Theatre: from the Little Theatre Guild

NASHVILLE COMMUNITY THEATRE: FROM THE LITTLE THEATRE GUILD TO THE NASHVILLE COMMUNITY PLAYHOUSE A THESIS IN Theatre History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri – Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by ANDREA ANDERSON B.A., Trevecca Nazarene University, 2003 Kansas City, Missouri 2012 © 2012 ANDREA JANE ANDERSON ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE LITTLE THEATRE MOVEMENT IN NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE: THE LITTLE THEATRE GUILD AND THE NASHVILLE COMMUNITY PLAYHOUSE Andrea Jane Anderson, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri - Kansas City, 2012 ABSTRACT In the early 20th century the Little Theatre Movement swept through the United States. Theatre enthusiasts in cities and towns across the country sought to raise the standards of theatrical productions by creating quality volunteer-driven theatre companies that not only entertained, but also became an integral part of the local community. This paper focuses on two such groups in the city of Nashville, Tennessee: the Little Theatre Guild of Nashville (later the Nashville Little Theatre) and the Nashville Community Playhouse. Both groups shared ties to the national movement and showed a dedication for producing the most current and relevant plays of the day. In this paper the formation, activities, and closure of both groups are discussed as well as their impact on the current generation of theatre artists. iii APPROVAL PAGE The faculty listed below, appointed by the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, have examined a thesis titled “Nashville Community Theatre: From the Little Theatre Guild to the Nashville Community Playhouse,” presented by Andrea Jane Anderson, candidate for the Master of Arts degree, and certify that in their opinion it is worthy of acceptance. -

Mckittrick, Casey. "Hitchcock's Hollywood Diet."

McKittrick, Casey. "Hitchcock’s Hollywood diet." Hitchcock’s Appetites: The corpulent plots of desire and dread. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 21–41. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 30 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501311642.0005>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 30 September 2021, 09:01 UTC. Copyright © Casey McKittrick 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 1 Hitchcock ’ s Hollywood diet lfred Joseph Hitchcock ’ s 1939 relocation from his native London to Los AAngeles set the stage for a surreal indoctrination into a culture he had only glimpsed through the refractions of the silver screen. Signing with SIP meant much more than leaving the homeland that had embraced him with growing enthusiasm as a national treasure over a fi fteen-year directorial career. It meant more than adapting to new and cutting edge fi lm technologies, more than submitting to the will of an erratic and headstrong studio boss. It also signaled his entrance into a milieu that demanded public, almost quotidian, access to his body. Consequently, it required a radical reassessment of his relationship to his body, and an intensifi cation of self-surveillance and heightened self- consciousness. In making the move to America, it is impossible to say how much Hitchcock had anticipated this rigorous negotiation of his celebrity persona. He discovered quickly that playing the Hollywood game required a new way of parsing the corporeal, and it made impossible the delusion — had he ever entertained one — of living or directing fi lms with any sense of disembodiment. -

A History of the Speech and Drama Department at North

-7R A HISTORY OF THE SPEECH AND DRAMA DEPARTMENT AT NORTH TEXAS STATE UNIVERSITY AS IT RELATES TO GENERAL TRENDS IN SPEECH EDUCATION 1890-1970 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE By Mildred J. Sandel, B. S. Denton, Texas August, 1971 Sandel, Mildred J., A History of the Speech and Drama Department at North Texas State Universit a it Relates to General Trends in peeh Education LS-97. Master of Science (Speech and Drama) August, 1971, 189 pp., 6 tables, 3 appendices, bibliography, 53 titles. Training in oral discourse has been offered in a virtually continuous and increasingly diversified curriculum from the founding of North Texas as a private normal college to 1970. The purpose of this study is to compare the training given at North Texas State University to national trends in speech education. The hypothesis for such a study is that historical comparisons may be beneficial to scholars as in- dicative of those methods that have met with the greatest success. The thesis is divided into five chapters. Chapter I introduces the study, establishes the format of the remaining chapters, and gives the historical trends in speech education in the United States. The historical trends were established from publications of the Speech Association of America, where they were available, and from publications of the regional associations or records of representative institutions of higher learning when no composite studies existed. 1 2 The trends in speech education at North Texas were re- corded from the official records of the university, including Bulletins, Capus Chat, Yucca, records of the Registrar and official records of audits, faculty committees, and similar reports. -

Facing Jazz, Facing Trauma: Modern Trauma and the Jazz Archive

Facing Jazz, Facing Trauma: Modern Trauma and the Jazz Archive By Tyfahra Danielle Singleton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Judith Butler, Chair Professor Chana Kronfeld Professor Linda Williams Fall 2011 Facing Jazz, Facing Trauma: Modern Trauma and the Jazz Archive Copyright © 2011 by Tyfahra Danielle Singleton Abstract Facing Jazz, Facing Trauma: Modern Trauma and the Jazz Archive by Tyfahra Danielle Singleton Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Judith Butler, Chair ―Facing Jazz, Facing Trauma‖ posits American jazz music as a historical archive of an American history of trauma. By reading texts by Gayl Jones, Ralph Ellison, Franz Kafka; music and performances by Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday; the life, art and films of Josephine Baker, and the film The Jazz Singer (1927), my goal is to give African American experiences of trauma a place within American trauma studies and to offer jazz as an extensive archive of testimony for witnessing and for study. Initially, I explore the pivotal historical moment where trauma and jazz converge on a groundbreaking scale, when Billie Holiday sings ―Strange Fruit‖ in 1939. This moment illuminates the fugitive alliance between American blacks and Jews in forming the historical testimony that is jazz. ―Strange Fruit,‖ written by Jewish American Abel Meeropol, and sung by Billie Holiday, evokes the trauma of lynching in an effort to protest the same. -

NINOTCHKA (1939, 110 Min)

February 1, 2011 (XXII:3) Ernst Lubitsch, NINOTCHKA (1939, 110 min) Directed by Ernst Lubitsch Written by Charles Brackett, Billy Wilder, Walter Reisch, Melchior Lengyel (story) Produced by Ernst Lubitsch and Sidney Franklin Cinematography by William H. Daniels Edited by Gene Ruggiero Art Direction by Cedric Gibbons Costume Design by Adrian Greta Garbo...Ninotchka Melvyn Douglas...Leon Ina Claire...Swana Bela Lugosi...Razinin Sig Ruman...Iranoff Felix Bressart...Buljanoff Alexander Granach...Kopalski Gregory Gaye...Rakonin CHARLES BRACKETT (November 26, 1892, Saratoga Springs, New National Film Registry 1990 York – March 9, 1969, Los Angeles, California) won four Academy Awards: 1946 – Best Screenplay (The Lost Weekend) – shared w. ERNST LUBITSCH (January 28, 1892, Berlin, Germany – November Billy Wilder; 1951 – Best Screenplay (Sunset Blvd.) – w. Billy 30, 1947, Hollywood, California) won an honorary Academy Wilder, D.M. Marshman Jr.; 1954 – Best Screenplay (Titanic) – w. Award in 1947. He directed 47 films, some of which were 1948 Walter Reisch, Richard L. Breen; and 1958 – Honorary Award – That Lady in Ermine, 1946 Cluny Brown, 1943 Heaven Can Wait, (“for outstanding service to the Academy”). He has 46 1942 To Be or Not to Be, 1941 That Uncertain Feeling, 1940 The screenwriting titles, some of which are 1959 Journey to the Center Shop Around the Corner, 1939 Ninotchka, 1938 Bluebeard's Eighth of the Earth, 1956 “Robert Montgomery Presents”, 1955 The Girl Wife, 1937 Angel, 1935 La veuve joyeuse, 1934 The Merry Widow, in the Red Velvet -

Sex, Politics, and Comedy

SEX, POLITICS, AND COMEDY GERMAN JEWISH CULTURES Editorial Board: Matthew Handelman, Michigan State University Iris Idelson-Shein, Goethe Universitat Frankfurt am Main Samuel Spinner, Johns Hopkins University Joshua Teplitsky, Stony Brook University Kerry Wallach, Gettysburg College Sponsored by the Leo Baeck Institute London SEX, POLITICS, AND COMEDY The Transnational Cinema of Ernst Lubitsch Rick McCormick Indiana University Press This book is a publication of Indiana University Press Office of Scholarly Publishing Herman B Wells Library 350 1320 East 10th Street Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA iupress.indiana.edu Supported by the Axel Springer Stiftung This book is freely available in an open access edition thanks to TOME (Toward an Open Monograph Ecosystem)—a collaboration of the Association of American Universities, the Association of University Presses, and the Association of Research Libraries—and the generous support of the University of Minnesota. Learn more at the TOME website, which can be found at the following web address: openmonographs.org. © 2020 by Richard W. McCormick All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992. -

Article Title: Subtitle in Same Font Frbrization: a Method for Turning Online Public Finding Lists Into Online Public Catalogs

FRBRization: A Method for Turning Online Public Finding Lists into Online Public Catalogs Item Type Journal (Paginated) Authors Yee, Martha M. Citation FRBRization: A Method for Turning Online Public Finding Lists into Online Public Catalogs 2005-06, 24(3):77-95 Information Technology and Libraries Publisher ALA (LITA) Journal Information Technology and Libraries Download date 28/09/2021 00:10:30 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/106459 FRBRization: A Method for Turning OnlineArticle PublicTitle: Finding Lists into Onlinesubtitle Public in same Catalogs font Martha M. Yee In this article, problems users are having searching authors (such as translators), and for the work itself, as for known works in current online public access catalogs well as by multiple bibliographic records for its various expressions/manifestations. Then I will briefly review (OPACs) are summarized. A better understanding of the FRBR entities with emphasis on the entities work, AACR2R/MARC 21 authority, bibliographic, and hold- expression, and manifestation. Next, I will point out ings records would allow us to implement the approaches where work identifiers exist in our current AACR2R and outlined in the IFLA Functional Requirements for MARC 21 bibliographic and authority records. I will then discuss the difficulties of using computer algorithms to Bibliographic Records to enhance, or “FRBRize,” our identify expressions/manifestations (formerly known as current OPACs using existing records. The presence editions), as some of the FRBRization projects do, since of work and expression identifiers in bibliographic and the records were designed to impart such information authority records is analyzed. Recommendations are made to humans, not to machines. -

An Evening of Jewish and Israeli Jazz

The Zamir Chorale of Boston Joshua Jacobson, Artistic Director Jazzamir An Evening of Jewish and Israeli Jazz Sunday, June 6, 2010 Sanders Theatre, Cambridge Program I Got Rhythm (from Girl Crazy) George Gershwin (arr. C. Clapham) Deborah Melkin, solo Summertime (from Porgy and Bess) George Gershwin Susan Rubin, solo There’s a Boat (from Porgy and Bess) George Gershwin (arr. R. Solomon) Peter Bronk, Lawrence E. Sandberg, Sarah Boling, Anne Levy, soli Yiddisha Charleston Fred Fisher (arr. A. Bailey & J. Jacobson) Ba Mir Bistu Sheyn Sholom Secunda (arr. A. Bailey & J. Jacobson) Susan Rubin, Deborah Melkin, Deborah West, trio And the Angels Sing Ziggy Elman (arr. A. Bailey & J. Jacobson) Oy Mame, Bin Ikh Farlibt Abe Ellstein (arr. J. Jacobson) Lidiya Yankovskaya, solo Adon Olam (from And David Danced before the Lord) Charles Davidson Susan Rubin, solo Kiddush Kurt Weill Hal Katzman, solo Shout unto the Lord (from Gates of Justice) Dave Brubeck Ron Williams, baritone, guest soloist; David Burns, tenor solo Shir Ahavah Jef Labes Susan Rubin, solo Niga El Ha-Khalom Shalom Hanoch (arr. Tz. Sherf) Anne Levy, solo Venezuela Moshe Wilensky (arr. A. Bailey & J. Jacobson) Richard Lustig, solo Kafe Bekef Ben Oakland (arr. Tz. Sherf) Elana Rome, solo Dem Dry Bones trad. (arr. L. Gearhart) The Zami r Chorale of Boston Soprano Elise Barber • Betty Bauman • Sharon Goldstein • Marilyn J. Jaye Anne Levy • Elana Rome • Susan Rubin • Sharon Shore • Louise Treitman Heather Viola • Deborah West • Lidiya Yankovskaya Alto Sarah Boling • Susan Carp-Nesson • Johanna Ehrmann • Hinda Eisen Alison Fields • Silvia Golijov • Deborah Melkin • Rachel Miller • Jill Sandberg Nancy Sargon-Zarsky • Phyllis Werlin • Phyllis Sogg Wilner Tenor David Burns • Steven Ebstein • Ethan Goldberg • Suzanne Goldman Hal Katzman • Daniel Nesson • Leila Joy Rosenthal • Lawrence E. -

Alan Crosland, the JAZZ SINGER (1927, 88 Min)

August 27, 2013 (XXVII:1) Alan Crosland, THE JAZZ SINGER (1927, 88 min) Academy Awards—1929—Honorary Award (Warner Bros.) for producing The Jazz Singer, the pioneer outstanding talking picture, which has revolutionized the industry. National Film Registry—1996 Directed by Alan Crosland Adapted for film by Alfred A. Cohn Based on the short story by Samson Raphaelson (“The Day of Atonement”) Original music by Louis Silvers Cinematography by Hal Mohr Edited by Harold McCord Al Jolson...Jakie Rabinowitz May McAvoy...Mary Dale Warner Oland...The Cantor Eugenie Besserer...Sara Rabinowitz Otto Lederer...Moisha Yudelson Crossland directed John Barrymore in Don Juan, which had sync Richard Tucker...Harry Lee sound effects and music, but no dialogue, using Vitaphone. Cantor Joseff Rosenblatt…Cantor Rosenblatt - Concert Recital SAMSON RAPHAELSON (b. March 30, 1894, New York City, ALAN CROSLAND (b. August 10, 1894, New York City, New New York—d. July 16, 1983, New York City, New York) has 45 York—d. July 16, 1936, Hollywood, California, car accident) writing credits, among them 1988 “American Playhouse,” 1980 directed 68 films, among them 1936 The Case of the Black Cat, The Jazz Singer (play), 1965 “Wolken am Himmel,” 1959 1935 The Great Impersonation, 1935 King Solomon of “Startime,” 1956 Hilda Crane (play), 1955 “Lux Video Theatre,” Broadway, 1935 It Happened in New York, 1935 The White 1952 “Broadway Television Theatre,” 1949 “The Ford Theatre Cockatoo, 1934 The Case of the Howling Dog, 1934 Massacre, Hour” 1949 In the Good Old Summertime, 1947 -

THE BOX OFFICE CHECK-UP of 1935

1 to tell the world!* IN 1936 THE BOX OFFICE CHECK-UP of 1935 An annual produced by the combined editorial and statistical facilities of Motion Picture Herald and Motion Picture Daily devoted to the records and ratings of talent in motion pictures of the year. QUIGLEY PUBLISHING COMPANY THE PUBLIC'S MANDATE by MARTIN QUIGLEY 1 The Box Office Check-Up is intended to disclose guidance upon that single question which in the daily operations of the industry over- shadows all others; namely, the relative box office values of types and kinds of pictures and the personnel of production responsible for them. It is the form-sheet of the industry, depending upon past performances for future guidance. Judging what producers, types of pictures and personalities will do in the future must largely depend upon the record. The Box Office Check-Up is the record. Examination of the record this year and every year must inevitably dis- close much information of both arresting interest and also of genuine im- portance to the progress of the motion picture. It proves some conten- tions and disproves others. It is a source of enlightenment, the clarifying rays of which must be depended upon to light the road ahead. ^ Striking is the essential character of those pictures which month in and month out stand at the head of the list of Box Office Cham- pions. Since August, 1934, the following are among the subjects in this classification: "Treasure Island," "The Barretts of Wimpole Street," "Flirta- tion Walk," "David Copperfield," "Roberta," "Love Me Forever," "Curley