1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 5Th Annual Harry Potter Conference

Draft Conference Schedule, Page 1 of 3 th The 5 AnnualChestnut Harry Hill Potter College Conference Friday October 21st, 2016 8:00-8:45AM Conference Arrival & Badge Pickup (Rotunda; Refreshments Provided) 8:45-8:55 Conference Welcome (East Parlor/Redmond Room) 9:00-10:15 Conference Section A (Concurrent Sessions) 1) Character Analyses I: Hogwarts & Professors (East Parlor) Kim, BA, Reading Snape's Mind: The Occlumency Lessons T. Jennings, BA (California State University Fullerton), Dumbledore’s Road To Hell: How His Good Intentions Nearly Led To Voldemort’s Victory L. Ryan, MS (Montclair State University), Transformational Dumbledore: A Critical Analysis of the Wizarding World’s Greatest Leader 2) Heroes and Villains (Redmond Room) J. Granger, Unlocking H.P.: An Invitation and Introduction to the Seven Keys to Rowling's Artistry and Meaning C. Roncin (Kutztown University), Teaching Joseph Campbell's Hero Theory Through H.P. D. Gras (Christ Community Chapel), Harry Potter: The Chosen One – Love’s Victory Over Death K. Peterman (Rutgers University), Utilization of Child Abuse in the H.P. Series 3) Film Analyses I (SJH 243) J. Ambrose, MA (Delaware County Community College), Mixed Messages: Gender Stereotypes in the Goblet of Fire Film E. Strand, MA (Mt. Carmel College of Nursing), Star Wars and H.P.: Commonalities, Cross-Influences and Shared Sources J. Roberts, MM, Magical, Musical Maturation: Examining the Use of “Hedwig’s Theme” in the H.P. Films L. Stevenson (University of Notre Dame), “Accio, Author!”: Dispersal and Convergence of Authorships in the H.P. Franchise 4) Textual Analyses I (SJH 245) B. Fish, BA (University of N. -

Spectacles of Light, Fire, and Fog: Artichoke and the Art of the Ephemeral

Spectacles of Light, Fire, and Fog: Artichoke and the Art of the Ephemeral Francisco LaRubia-Prado Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA What does Christ’s crucifixion have in common with George Floyd’s video-recorded murder, Donald Trump’s reality TV-like Presidency, popular festivals like Mardi Gras, and the advertising and news media images that flood our daily existence? The answer is that all of the above have been considered “spectacles” by critics in various fields; and, in fact, they share key features when regarded as a “spectacle.” Furthermore, all have had — or can have — a significant impact at the individual, local, national, and/or global levels. 1 Historically, spectacle emerges as an as the sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland, inevitable phenomenon in any society, and is unemployment, violence, and gender crucial to promote a sense of identity and inequality— through stunning spectacles that community. It also provides education and place art at their core. Later in this essay, I will entertainment, and is used to enforce the law and examine some of these events. maintain the social order. Leading up to the present day, spectacle becomes even more The field of “Festival studies” has central to culture due to the increasing frequently analyzed how spectacle has the power importance of the mass media. Yet, spectacle to engage citizens in their communities while rejects any a priori ethical alignment; namely, it countering social isolation.3 In the belief that it can possess a bright or a dark character. Because would -

Bellwether 54, Fall 2002

Bellwether Magazine Volume 1 Number 54 Fall 2002 Article 1 Fall 2002 Bellwether 54, Fall 2002 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/bellwether Part of the Veterinary Medicine Commons Recommended Citation (2002) "Bellwether 54, Fall 2002," Bellwether Magazine: Vol. 1 : No. 54 , Article 1. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/bellwether/vol1/iss54/1 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/bellwether/vol1/iss54/1 For more information, please contact [email protected]. No.54 • Fall 2002 ® School of Veterinary Medicine UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA BellwetherTHE NEWSMAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA SCHOOL OF VETERINARY MEDICINE The New Animal Bloodmobile Page 4 Inside 2From the Dean 6 Scott Building Dedicated 11 V.M.D.Notes 25 Feline Symposium 31 Dr.Deubler’s Birthday 12 Alumni Weekend 16 Commencement A Message from the Dean Despite the awful tragedy of September 11, new gifts and pledges with $13.4 million raised $3 million grant from the Ellison Foundation 2001, anthrax threats to homeland security, by June 30, 2002. In cash receipts, we had our for studying gene manipulation in nematode Osama bin Laden, the down turn in the econ- second best year ever at $8.1 million. We were parasites, and Dr. Narayan Avadhani received a omy, Enron, WorldCom, and ImClone, it is especially fortunate to attract significant new $500,000 grant from NIH to purchase state-of- nice to be in support for the Teaching and Research Build- the-art equipment for proteomics. the position ing, securing $7.5 million in new commit- Finally, I am very pleased to share with you of reporting ments from individuals and private founda- that we are at last making progress in revising some very tions. -

Harry Potter Is a Hobbit: Rowling, Tolkien, and the Question of Readership by Amy H

The Bulletin of CSL The New York C.S. Lewis Society May/June 2004 Vol. 35, No. 3 Whole No. 401 Harry Potter Is A Hobbit: Rowling, Tolkien, and The Question of Readership by Amy H. Sturgis J.K. Rowlings Harry Potter novels have redefined commercial literary success, and yet, oddly enough, no clear consensus exists about who is the proper audience for the books. Rowling has drawn surprise and even criticism for the dark gravity of her subjects and fierce action of her plots, leading some to suggest that the so-called childrens series is unsuitable for the youngsters to whom it is marketed by publishers and booksellers. This conviction at times even translates into formal written complaints and legal actions lodged against elementary schools and libraries. In fact, the Harry Potter novels have continually C.S. Lewis topped the American Library Associations Most Challenged Books List, and the series as a whole ranked as the seventh most challenged book of the decade 1990-2000, no small feat Contents since the first volume, Harry Potter and the Sorcerers Stone, did not debut until 1998.1 Harry Is a Hobbit 1 Future Meetings 11 Although religious convictions lead some individuals to Private Passions in Public Square 16 denounce Harry Potter and the tradition of fantasy to which he Three Book Reviews 18 belongs,2 other adults who embrace such literature still worry Report of the February Meeting 22 about Rowlings work in particular, fearing its themes might prove Bits and Pieces 23 too much for young readers. In their article Controversial Content Report of the March Meeting 24 in Childrens Literature: Is Harry Potter Harmful to Children?, Deborah J. -

Fesmire 1 Literary Alchemy and the Transformation of The

Fesmire 1 Literary Alchemy and the Transformation of the Transformation William Thomas Fesmire Fesmire 2 Literary Alchemy and the Transformation of the Transformation William Thomas Fesmire Professor Mark Schoenfield: ________________________________ Professor Jessie Hock: ________________________________ Professor Scott Juengel: ________________________________ Submitted to the Department of English, Vanderbilt University, In partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major, April 17, 2020 Fesmire 3 Abstract Alchemy is a pseudoscience that has persisted throughout millennia as a result of its own ability to change while retaining its primary purpose: transformation. What began as a means of wielding and evolving metals developed into both a scientific and spiritual quest. Eventually, alchemy was no longer considered a viable science; however, it became a philosophical and psychological framework for analyzing internal transformation. This transformation of alchemy can be seen in literature throughout time. Authors have incorporated elements of the alchemical process into their own works, creating a “literary alchemy” with the same purpose of transformation. After an introduction to alchemy and literary alchemy, this thesis will present four permutations of literary alchemy in Western Literature—William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Ben Jonson’s The Alchemist, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter—in three separate time periods to demonstrate how literary alchemy both reflects the attitudes towards alchemy in the respective time period and remains consistent in its message of transformation. Fesmire 4 Table of Contents Acknowledgments 5 Dedication 6 Preparation An Introduction to Alchemy and Literary Alchemy 8 Nigredo The Alchemy of the Stage 20 Albedo Refining Literary Alchemy through Frankenstein 36 Rubedo A Conclusion through Harry Potter, Jung, and Nostalgia 56 Bibliography 71 Fesmire 5 Acknowledgments Mark Schoenfield, you have been stuck with me the longest, and I thank you for guiding me this whole process. -

The Harry Potter Conference

The Harry Potter Conference Academic Reflections on the Major Themes 2014 in J.K. Rowling’s Literature Chestnut Hill College October 17, 2014 Harry Potter Conference Art Exhibit (Rotunda) Susan Bradbury, MAOL, Medaille College “Life Story” (Mixed Media) “Role Model” (Mixed Media) Joseph J. Calabresi, BA, Independent Illustrator “Expecto Patronum” “Harry is Alone” (Mixed Media) (Mixed Media) Patrick McCauley, PhD, Chestnut Hill College “Selected Chapter Heading Illustrations for Into the Pensieve: The Philosophy & Mythology of Harry Potter” (Schiffer Publishing, 2015) (Mixed Media) Conference Overview Pre-Conference Schedule 11:30AM – 2:00PM: Registration (Rotunda) 12noon – 1PM: High School Student Conference Presentations (East Parlor) 1:00 – 6:00PM: Harry Potter Art Exhibit & Refreshments (Rotunda) The Harry Potter Conference 2:00 – 2:10PM: Conference Introduction & High School Student Conference Award Ceremony (East Parlor) 2:10 – 2:55PM: Opening Plenary Lecture (East Parlor) John Granger, Independent Scholar “What Cormoran Strike, Private Investigator, Teaches Us About the Hogwarts Saga” 3:00 – 5:00 PM: Concurrent Conference Sections Section A: Gender, Politics & Psychology (East Parlor) Section B: Philosophy & Literature (Redmond Room) Section C: Education & History (Second Floor, SJH 245) 5:10 – 5:55PM: Closing Plenary Lecture (East Parlor) Gregory Bassham, King’s College “Harry Potter and the Meaning of Life” 5:55 – 6:00PM: Conference Conclusion Conference Map High School Student Conference Presentations 12 noon – 1PM (East Parlor) -

Rachel Jelinek English Senior Honors Thesis Dr. Johanna Kramer 5 May 2016 from the Bible to Harry Potter

Rachel Jelinek English Senior Honors Thesis Dr. Johanna Kramer 5 May 2016 From the Bible to Harry Potter: Updating an ancient myth into modern fantasy The Harry Potter series began in 1997 and concluded in 2007. In a matter of ten years, the series joined the ranks of the most read books in the world, with 400 million copies sold as of 2015, according to writer James Chapman (“10 Most Read Books in the World”). The Harry Potter series phenomenon, though, faced criticism in the United States by those who believed the books promoted witchcraft and occultism, and so the books were banned in many libraries across the nation. These controversies have also affected critical scholarship about the books resulting in much of the existing research focusing on religious controversy rather than on critical analysis of the Harry Potter series. In my thesis, I leave the controversies aside and instead focus on what the Harry Potter series means for readers and what the driving elements are behind readers’ attraction to the series today. A series that has had a dominant presence in modern culture is worthwhile investigating to discover what about the books has brought them to their stunning popularity. I argue throughout the remainder of my thesis that through Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallow’s (hereafter Harry Potter DH) completion of the Bible, and its position in the fantasy genre, modern-day readers find Harry Potter DH an approachable text to explore the complex universal questions all humans have. When examining the dominant themes and symbols found in Harry Potter DH, it is apparent that these elements parallel those found in the Bible. -

An Exploration of Twins in the Wizarding World

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-16-2014 Twin Core: An Exploration of Twins in the Wizarding World Carol R. Eshleman [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Eshleman, Carol R., "Twin Core: An Exploration of Twins in the Wizarding World" (2014). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1793. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1793 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Twin Core : An Exploration of Twins in the Wizarding World A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English by Carol Eshleman B.A. Loyola University of New Orleans 2003 May2014 Table of Contents Introduction -

Resurrection in Paganism and the Question of an Empty Tomb in 1 Corinthians 15*

Cambridge University Press, 2016 © .־New Test. Stud. (2017)» 63» pp. 5675 doi:10.1017/S002868851600028X Resurrection in Paganism and the Question of an Empty Tomb in 1 Corinthians 15* JOHN GRANGER COOK Religion and Philosophy; LaGrange College, 60i Broad St., LaGrange, GA 30240, USA. Email: [email protected] ־On the basis of the semantics of άνίστημι and εγείρω and the nature of resur rected bodies in ancient Judaism and ancient paganism, one can conclude that Paul could not have conceived of a resurrection of Jesus unless he believed the tomb was empty. empty tomb, resurrection in paganism ,־Keywords: 1 Cor 15-35 Wilhelm Bousset, one of the original members of the religionsgeschichtliche -wrote: ‘Here it is now extraordinarily im ,־Schule, in his discussion of 1 Cor 15.35 portant that the Apostle says nothing either concerning the empty tomb or con- cerning the witness of the women about the empty tomb. What he does not say, one cannot wish to read between the lines/1 This is an argumentum exsilentio and as such is logically invalid. Nevertheless, Bousset's approach has become pro- grammatic for many scholars in the discipline.2 My thesis is that Paul could not have conceived of a resurrection of Jesus unless he believed his tomb was empty. The intention of the article is certainly not to prove the historicity of the empty tomb - a poindess exercise after the arguments of David Hume.3 The argument schema for the thesis is as follows: * I am grateful for comments on the article made by the NTS reviewer, by historians of religion Jan Bremmer and Jorunn Jacobsen Buckley, and by philosopher Ian Morton. -

Introduction: Why Harry?

Notes Introduction: Why Harry? 1. J. K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (New York: Scholastic, 1997), 17. (Said by Minerva McGonagall to Albus Dumbledore.) 2. BBC News, “Harry Potter Finale Sales Hit 11m,” BBC News, July 23, 2007; Motoko Rich, “Record First- Day Sales for Last ‘Harry Potter’ Book,” New York Times, July 22, 2007. 3. Ben Fritz, “Box Office, Harry Potter Hits New Heights, Russell Crowe Flops,” Los Angeles Times, November 21, 2010, http://latimesblogs.latimes. com/entertainmentnewsbuzz/2010/11/box- office- harry- potter- hits- new - heights- russell- crowe- flops.html. 4. See, for example, Susan Gunelius, Harry Potter: The Story of a Global Business Phenomenon (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008). 5. http://www.jkrowling.com/. 6. Shayna Garlick, “Harry Potter and the Magic of Reading,” Christian Science Monitor, May 2, 2007, http://www.csmonitor.com/2007/0502/p13s01- legn .html. 7. Yankelovich and Scholastic, 2008 Kids & Family Reading Report: Reading in the 21st Century: Turning the Page with Technology (New York: Scholastic, 2008). It is important to note the potential for bias in research commissioned by the publisher of the book; we provide these statistics not as definitive proof of the series’ impact, but one piece of evidence of the value of the Potter books. 8. Harrison Group and Scholastic, 2010 Kids & Family Reading Report: Turning the Page in the Digital Age (New York: Scholastic, 2010). 9. Edmund Kern, The Wisdom of Harry Potter: What Our Favorite Hero Teaches Us about Moral Choices (New York: Prometheus Books, 2003), 14. 10. Gloria Ladson- Billings, The Dreamkeepers: Successful Teachers of African American Children, 2nd ed. -

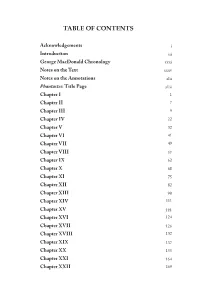

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements i Introduction iii George MacDonald Chronology xxxi Notes on the Text xxxv Notes on the Annotations xlii Phantastes: Title Page xliii Chapter I 1 Chapter II 7 Chapter III 9 Chapter IV 22 Chapter V 32 Chapter VI 41 Chapter VII 49 Chapter VIII 57 Chapter IX 62 Chapter X 68 Chapter XI 75 Chapter XII 82 Chapter XIII 90 Chapter XIV 111 Chapter XV 118 Chapter XVI 124 Chapter XVII 126 Chapter XVIII 132 Chapter XIX 137 Chapter XX 155 Chapter XXI 164 Chapter XXII 169 Chapter XXIII 177 Chapter XXIV 189 Chapter XXV 193 Appendix A: Phantastes and Novalis’ Epigraph 197 Appendix B: Reviews and Responses to Phantastes 199 1) Athenæum (1858) 2) The Leader (1858) 3) Spectator (1858) 4) The Globe (1858) 5) The Eclectic Review (1859) 6) British Quarterly Review (1859) Review of Phantastes after MacDonald’s Death 7) Stanley Robertson, “A Literary Causerie: Phantastes,” The Academy (1906) Review of Phantastes in Commemoration of MacDonald’s Centenary Birth 8) H. J. C. Grierson, “George MacDonald,” The Aberdeen University Review (1924) Appendix C: German Romantics and other Influences 216 1) Edmund Spenser, from The Faerie Queene (1590) 2) Phineas Fletcher, from The Purple Island (1633) 3) Novalis, from Heinrich von Ofterdingen, A Romance (1800) a: “Longing for Death” from Hymns to the Night (1800) 4) Wordsworth, “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood” (1802-1804; 1807) a: From The Prelude (1850) 5) Robert Blair, from “The Grave” (1743) a) Illustrations by William Blake 6) Samuel Taylor Coleridge, “Dejection: An Ode” (1802) 7) Friedrich von Shiller, “Longing” (1813) 8) Adelbert von Chamisso, from Peter Schlemihl (1814) a: Illustration by George Cruikshank 9) E. -

Happy Anniversary from the President’S Desk

SPRING 2007 VOLUME XII NO. 3 The Magazine of Wright State University Happy Anniversary From the President’s Desk SPRING 2007 VOLUME XII NO. 3 Managing Editor Denise Thomas Office of Communications and Marketing Editor Connie Steele Office of Communications and Marketing Design Theresa Almond Office of Communications and Marketing Cover Image William Jones, Center for Teaching and Learning WELCOME TO THIS SPECIAL ANNIVERSARY ISSUE OF Contributing Writers COMMUNITY MAGAZINE. John Bennett, Richard Doty, Stephanie James Ely, Jane Schreier Jones, Cindy Young, Connie Steele I find it especially rewarding that the same year I begin my tenure as WSU’s sixth president is also the same year that the university is celebrating its 40th Photography William Jones, Center for Teaching and Learning anniversary. Campus spirit is high: we’ve had an overwhelming response to an impressive lineup of speakers for the Honors Institute and Presidential Lecture Digital Imaging Manipulation Chris Snyder, Center for Teaching and Learning Series; colleges and departments have hosted an array of special reunion events; Cover Cake Design an all-class reunion hosted by the Office of Alumni Relations was a huge success. The Cakery There’s a special anniversary Web site (www.wright.edu/40years), and even a blog Community is published two times a year by the site (www.libraries.wright.edu/40th_wsu) where you can add your own personal Office of Communications and Marketing, Divi- comments, photographs, and memories of Wright State. And of course, who can sion of University Advancement. Distribution is forget March Madness when the Raiders won the Horizon League championship to Wright State alumni, faculty, staff, and friends of the university.