Implementing Modulation Functions in Microwave Frequency Synthesizers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microwave Frequency Demodulation Using Two Coupled Optical Resonators with Modulated Refractive Index

PHYSICAL REVIEW APPLIED 15, 034056 (2021) Microwave Frequency Demodulation Using two Coupled Optical Resonators with Modulated Refractive Index Adam Mock * School of Engineering and Technology, Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant, Michigan 48859, USA (Received 16 October 2020; revised 1 February 2021; accepted 10 February 2021; published 18 March 2021) Traditional electronic frequency demodulation of a microwave frequency voltage is challenging because it requires complicated phase-locked loops, narrowband filters with fixed passbands, or large footprint local oscillators and mixers. Herein, a different frequency demodulation concept is proposed based on refractive index modulation of two coupled microcavities excited by an optical wave. A frequency- modulated microwave frequency voltage is applied to two photonic crystal microcavities in a spatially odd configuration. The spatially odd perturbation causes coupling between the even and odd supermodes of the coupled-cavity system. It is shown theoretically and verified by finite-difference time-domain sim- ulations how careful choice of the modulation amplitude and frequency can switch the optical output from on to off. As the modulating frequency is detuned from its off value, the optical output switches from off to on. Ultimately, the optical output amplitude is proportional to the frequency deviation of the applied voltage making this device a frequency-modulated-voltage to amplitude-modulated-optical- wave converter. The optical output can be immediately detected and converted to a voltage that would result in a frequency-demodulated voltage signal. Or the optical output can be fed into a larger radio- over-fiber optical network. In this case the device presents a compact, low power, and tunable route for multiplexing frequency-modulated voltages with amplitude-modulated optical communication systems. -

Additive Synthesis, Amplitude Modulation and Frequency Modulation

Additive Synthesis, Amplitude Modulation and Frequency Modulation Prof Eduardo R Miranda Varèse-Gastprofessor [email protected] Electronic Music Studio TU Berlin Institute of Communications Research http://www.kgw.tu-berlin.de/ Topics: Additive Synthesis Amplitude Modulation (and Ring Modulation) Frequency Modulation Additive Synthesis • The technique assumes that any periodic waveform can be modelled as a sum sinusoids at various amplitude envelopes and time-varying frequencies. • Works by summing up individually generated sinusoids in order to form a specific sound. Additive Synthesis eg21 Additive Synthesis eg24 • A very powerful and flexible technique. • But it is difficult to control manually and is computationally expensive. • Musical timbres: composed of dozens of time-varying partials. • It requires dozens of oscillators, noise generators and envelopes to obtain convincing simulations of acoustic sounds. • The specification and control of the parameter values for these components are difficult and time consuming. • Alternative approach: tools to obtain the synthesis parameters automatically from the analysis of the spectrum of sampled sounds. Amplitude Modulation • Modulation occurs when some aspect of an audio signal (carrier) varies according to the behaviour of another signal (modulator). • AM = when a modulator drives the amplitude of a carrier. • Simple AM: uses only 2 sinewave oscillators. eg23 • Complex AM: may involve more than 2 signals; or signals other than sinewaves may be employed as carriers and/or modulators. • Two types of AM: a) Classic AM b) Ring Modulation Classic AM • The output from the modulator is added to an offset amplitude value. • If there is no modulation, then the amplitude of the carrier will be equal to the offset. -

En 300 720 V2.1.0 (2015-12)

Draft ETSI EN 300 720 V2.1.0 (2015-12) HARMONISED EUROPEAN STANDARD Ultra-High Frequency (UHF) on-board vessels communications systems and equipment; Harmonised Standard covering the essential requirements of article 3.2 of the Directive 2014/53/EU 2 Draft ETSI EN 300 720 V2.1.0 (2015-12) Reference REN/ERM-TG26-136 Keywords Harmonised Standard, maritime, radio, UHF ETSI 650 Route des Lucioles F-06921 Sophia Antipolis Cedex - FRANCE Tel.: +33 4 92 94 42 00 Fax: +33 4 93 65 47 16 Siret N° 348 623 562 00017 - NAF 742 C Association à but non lucratif enregistrée à la Sous-Préfecture de Grasse (06) N° 7803/88 Important notice The present document can be downloaded from: http://www.etsi.org/standards-search The present document may be made available in electronic versions and/or in print. The content of any electronic and/or print versions of the present document shall not be modified without the prior written authorization of ETSI. In case of any existing or perceived difference in contents between such versions and/or in print, the only prevailing document is the print of the Portable Document Format (PDF) version kept on a specific network drive within ETSI Secretariat. Users of the present document should be aware that the document may be subject to revision or change of status. Information on the current status of this and other ETSI documents is available at http://portal.etsi.org/tb/status/status.asp If you find errors in the present document, please send your comment to one of the following services: https://portal.etsi.org/People/CommiteeSupportStaff.aspx Copyright Notification No part may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm except as authorized by written permission of ETSI. -

Amplitude Modulation(AM)

Introduction to Modulation: Amplitude Modulation(AM) Sharlene Katz James Flynn Overview Modulation Overview Basics of Amplitude Modulation (AM) AM Demonstration GRC Exercise 2 Flynn/Katz 7/8/10 Why do we need Modulation/Demodulation? Example: Radio transmission Voice Microphone Transmitter Electric signal, Antenna: 20 Hz – 20 Size requirement KHz > 1/10 wavelength c 3×108 Antenna too large! 5 Use modulation to At 3 KHz: λ = = 3 =10 =100km f 3×10 transfer ⇒ .1λ =10km information to a higher frequency 3 Flynn/Katz 7/8/10 Why do we need Modulation/Demodulation? (cont’d) Frequency Assignment Reduction of noise/interference Multiplexing Bandwidth limitations of equipment Frequency characteristics of antennas Atmospheric/cable properties 4 Flynn/Katz 7/8/10 Basic Concept of Modulation The information source Typically a low frequency signal Referred to as the “baseband signal” X(f) x(t) t f Carrier A higher frequency sinusoid baseband Modulated Modulator Example: cos(2π10000t) carrier signal Modulated Signal Some parameter of the carrier (amplitude, frequency, phase) is varied in accordance with the baseband signal 5 Flynn/Katz 7/8/10 Types of Modulation Analog Modulation Amplitude Modulation, AM Frequency Modulation, FM Double and Single Sideband, DSB and SSB Digital Modulation Phase Shift Keying: BPSK, QPSK, MSK Frequency Shift Keying, FSK Quadrature Amplitude Modulation, QAM 6 Flynn/Katz 7/8/10 Amplitude Modulation (AM) Block Diagram x(t) m x + xAM(t)=Ac [1+mx(t)]cos wct Ac cos wct Time Domain Signal information -

NTSC Specifications

NTSC Modulation Standard ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ The Impressionistic Era of TV. It©s Never The Same Color! The first analog Color TV system realized which is backward compatible with the existing B & W signal. To combine a Chroma signal with the existing Luma(Y)signal a quadrature sub-carrier Chroma signal is used. On the Cartesian grid the x & y axes are defined with B−Y & R−Y respectively. When transmitted along with the Luma(Y) G−Y signal can be recovered from the B−Y & R−Y signals. Matrixing ━━━━━━━━━ Let: R = Red \ G = Green Each range from 0 to 1. B = Blue / Y = Matrixed B & W Luma sub-channel. U = Matrixed Blue Chroma sub-channel. U #2900FC 249.76° −U #D3FC00 69.76° V = Matrixed Red Chroma sub-channel. V #FF0056 339.76° −V #00FFA9 159.76° W = Matrixed Green Chroma sub-channel. W #1BFA00 113.52° −W #DF00FA 293.52° HSV HSV Enhanced channels: Hue Hue I = Matrixed Skin Chroma sub-channel. I #FC6600 24.29° −I #0096FC 204.29° Q = Matrixed Purple Chroma sub-channel. Q #8900FE 272.36° −Q #75FE00 92.36° We have: Y = 0.299 × R + 0.587 × G + 0.114 × B B − Y = −0.299 × R − 0.587 × G + 0.886 × B R − Y = 0.701 × R − 0.587 × G − 0.114 × B G − Y = −0.299 × R + 0.413 × G − 0.114 × B = −0.194208 × (B − Y) −0.509370 × (R − Y) (−0.1942078377, −0.5093696834) Encode: If: U[x] = 0.492111 × ( B − Y ) × 0° ┐ Quadrature (0.4921110411) V[y] = 0.877283 × ( R − Y ) × 90° ┘ Sub-Carrier (0.8772832199) Then: W = 1.424415 × ( G − Y ) @ 235.796° Chroma Vector = √ U² + V² Chroma Hue θ = aTan2(V,U) [Radians] If θ < 0 then add 2π.[360°] Decode: SyncDet U: B − Y = -┼- @ 0.000° ÷ 0.492111 V: R − Y = -┼- @ 90.000° ÷ 0.877283 W: G − Y = -┼- @ 235.796° ÷ 1.424415 (1.4244145537, 235.79647610°) or G − Y = −0.394642 × (B − Y) − 0.580622 × (R − Y) (−0.3946423068, −0.5806217020) These scaling factors are for the quadrature Chroma signal before the 0.492111 & 0.877283 unscaling factors are applied to the B−Y & R−Y axes respectively. -

Saleh Faruque Radio Frequency Modulation Made Easy

SPRINGER BRIEFS IN ELECTRICAL AND COMPUTER ENGINEERING Saleh Faruque Radio Frequency Modulation Made Easy 123 SpringerBriefs in Electrical and Computer Engineering More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/10059 Saleh Faruque Radio Frequency Modulation Made Easy 123 Saleh Faruque Department of Electrical Engineering University of North Dakota Grand Forks, ND USA ISSN 2191-8112 ISSN 2191-8120 (electronic) SpringerBriefs in Electrical and Computer Engineering ISBN 978-3-319-41200-9 ISBN 978-3-319-41202-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-41202-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016945147 © The Author(s) 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

ES442 Lab 6 Frequency Modulation and Demodulation

ES442 Lab#6 ES442 Lab 6 Frequency Modulation and Demodulation Objective 1. Build simple FM demodulator by using frequency discriminator 2. Build simple envelope detector for FM demodulation. 3. Using MATLAB m-file and simulink to implement FM modulation and demodulation. Part List 1uF capacitor (2); 10.0Kohm resistor, 1.0Kohm resistor, Power supply with +/-5V, Scope and frequency analyzer, FM signal Generator. Estimated Time About 90 minutes. Introduction Frequency modulation is a form of modulation, which represents information as variations in the instantaneous frequency of a carrier wave. In analog applications, the carrier frequency is varied in direct proportion to changes in the amplitude of an input signal. This is shown in Fig. 1. Figure 1, Frequency modulation. The FM-modulated signal has its instantaneous frequency that varies linearly with the amplitude of the message signal. Now we can get the FM-modulation by the following: where Kƒ is the sensitivity factor, and represents the frequency deviation rate as a result of message amplitude change. The instantaneous frequency is: Ver 2. 1 ES442 Lab#6 The maximum deviation of Fc (which represents the max. shift away from Fc in one direction) is: Note that The FM-modulation is implemented by controlling the instantaneous frequency of a voltage-controlled oscillator(VCO). The amplitude of the input signal controls the oscillation frequency of the VCO output signal. In the FM demodulation what we need to recover is the variation of the instantaneous frequency of the carrier, either above or below the center frequency. The detecting device must be constructed so that its output amplitude will vary linearly according to the instantaneous freq. -

ETS 300 750 TELECOMMUNICATION May 1996 STANDARD

DRAFT EUROPEAN pr ETS 300 750 TELECOMMUNICATION May 1996 STANDARD Source: EBU/CENELEC/ETSI JTC Reference: DE/JTC-00VHFTXHU ICS: 33.060.20 Key words: broadcasting, radio, transmitter, FM, VHF, audio European Broadcasting Union Union Européenne de Radio-Télévision EBU UER Radio broadcasting systems; Very High Frequency (VHF), frequency modulated, sound broadcasting transmitters in the 66 to 73 MHz band ETSI European Telecommunications Standards Institute ETSI Secretariat Postal address: F-06921 Sophia Antipolis CEDEX - FRANCE Office address: 650 Route des Lucioles - Sophia Antipolis - Valbonne - FRANCE X.400: c=fr, a=atlas, p=etsi, s=secretariat - Internet: [email protected] Tel.: +33 92 94 42 00 - Fax: +33 93 65 47 16 Copyright Notification: No part may be reproduced except as authorized by written permission. The copyright and the * foregoing restriction extend to reproduction in all media. © European Telecommunications Standards Institute 1996. © European Broadcasting Union 1996. All rights reserved. Page 2 Draft prETS 300 750: May 1996 Whilst every care has been taken in the preparation and publication of this document, errors in content, typographical or otherwise, may occur. If you have comments concerning its accuracy, please write to "ETSI Editing and Committee Support Dept." at the address shown on the title page. Page 3 Draft prETS 300 750: May 1996 Contents Foreword .......................................................................................................................................................5 1 Scope -

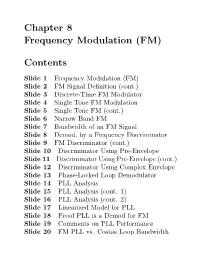

Chapter 8 Frequency Modulation (FM) Contents

Chapter 8 Frequency Modulation (FM) Contents Slide 1 Frequency Modulation (FM) Slide 2 FM Signal Definition (cont.) Slide 3 Discrete-Time FM Modulator Slide 4 Single Tone FM Modulation Slide 5 Single Tone FM (cont.) Slide 6 Narrow Band FM Slide 7 Bandwidth of an FM Signal Slide 8 Demod. by a Frequency Discriminator Slide 9 FM Discriminator (cont.) Slide 10 Discriminator Using Pre-Envelope Slide 11 Discriminator Using Pre-Envelope (cont.) Slide 12 Discriminator Using Complex Envelope Slide 13 Phase-Locked Loop Demodulator Slide 14 PLL Analysis Slide 15 PLL Analysis (cont. 1) Slide 16 PLL Analysis (cont. 2) Slide 17 Linearized Model for PLL Slide 18 Proof PLL is a Demod for FM Slide 19 Comments on PLL Performance Slide 20 FM PLL vs. Costas Loop Bandwidth Slide 21 Laboratory Experiments for FM Slide 21 Experiment 8.1 Making an FM Modulator Slide 22 Experiment 8.1 FM Modulator (cont. 1) Slide 23 Experiment 8.2 Spectrum of an FM Signal Slide 24 Experiment 8.2 FM Spectrum (cont. 1) Slide 25 Experiment 8.2 FM Spectrum (cont. 1) Slide 26 Experiment 8.2 FM Spectrum (cont. 3) Slide 26 Experiment 8.3 Demodulation by a Discriminator Slide 27 Experiment 8.3 Discriminator (cont. 1) Slide 28 Experiment 8.3 Discriminator (cont. 2) Slide 29 Experiment 8.4 Demodulation by a PLL Slide 30 Experiment 8.4 PLL (cont.) 8-ii ✬ Chapter 8 ✩ Frequency Modulation (FM) FM was invented and commercialized after AM. Its main advantage is that it is more resistant to additive noise than AM. Instantaneous Frequency The instantaneous frequency of cos θ(t) is d ω(t)= θ(t) (1) dt Motivational Example Let θ(t) = ωct. -

Recommendation Itu-R Bo.650-2*,**

Rec. ITU-R BO.650-2 1 RECOMMENDATION ITU-R BO.650-2*,** Standards for conventional television systems for satellite broadcasting in the channels defined by Appendix 30 of the Radio Regulations (1986-1990-1992) The ITU Radiocommunication Assembly, considering a) that the introduction of the broadcasting-satellite service offers the possibility of reducing the disparity between television standards throughout the world; b) that this introduction also provides an opportunity, through technological developments, for improving the quality and increasing the quantity and diversity of the services offered to the public; additionally, it is possible to take advantage of new technology to introduce time-division multiplex systems in which the high degree of commonality can lead to economic multi-standard receivers; c) that it will no doubt be necessary to retain 625-line and 525-line television systems; d) that broadcasting-satellite services are being introduced using analogue composite coding according to Annex 1 of Recommendation ITU-R BT.470 for the vision signal; e) that it is generally intended that broadcasting-satellite standards should facilitate the maximum utilization of existing terrestrial equipment, especially that which concerns individual and community reception media (receivers, cable, re-broadcasting methods of distribution etc.). For this purpose a unique baseband signal which is common to the satellite-broadcasting system and the terrestrial distribution network is desirable; f) that the requirements as regards sensitivity to interference of the systems that can be used were defined by Appendix 30 of the Radio Regulations (RR); g) that complete compatibility with existing receivers is in any event not possible for frequency-modulated satellite broadcasting transmissions; ____________________ * Note – The following Reports of the ITU-R were considered in relation with this Recommendation: ITU- R BT.624-4, ITU-R BO.632-4, ITU-R BS.795-3, ITU-R BT.802-3, ITU-R BO.953-2, ITU-R BO.954-2, ITU-R BO.1073-1, ITU-R BO.1074-1 and ITU-R BO.1228. -

Radio Theory the Basics Radio Theory the Basics Radio Wave Propagation

Radio Theory The Basics Radio Theory The Basics Radio Wave Propagation Radio Theory The Basics Electromagnetic Spectrum Radio Theory The Basics Radio Theory The Basics • Differences between Very High Frequency (VHF) and Ultra High Frequency (UHF). • Difference between Amplitude Modulation (AM) and Frequency Modulation (FM). • Interference and the best methods to reduce it. • The purpose of a repeater and when it would be necessary. Radio Theory The Basics VHF - Very High Frequency • Range: 30 MHz - 300 MHz • Government and public service operate primarily at 150 MHz to 174 MHz for incidents • 150 MHz to 174 MHz used extensively in NIFC communications equipment • VHF has the advantage of being able to pass through bushes and trees • VHF has the disadvantage of not reliably passing through buildings • 2 watt VHF hand-held radio is capable of transmitting understandably up to 30 miles, line-of-sight Radio Theory The Basics VHF ABSOLUTE MAXIMUM RANGE OF LINE-OF-SITE PORTABLE RADIO COMMUNICATIONS 165 MHz CAN TRANSMIT ABOUT 200 MILES Radio Theory The Basics UHF - Ultra High Frequency • 300 MHz - 3,000 MHz • Government and public safety operate primarily at 400 MHz to 470 MHz for incidents Radio Theory The Basics UHF - Ultra High Frequency • 400 MHz to 420 MHz used in NIFC equipment primarily for logistical communications and linking • Advantage of being able to transmit great distances (2 watt UHF hand-held can transmit 50 miles maximum…line-of-sight in ideal conditions) • UHF signals tend to “bounce” off of buildings and objects, making them -

Lecture 28-29 FM- Frequency Modulation PM

FM and PM Lecture 28-29 for FM: FM- Frequency Modulation PM - Phase Modulation Relationship between mf(t) and mp(t): EE445-10 1 3 FM and PM Figure 5–8 Angle modulator circuits. RFC = radio-frequency choke. Dp is the phase sensitivity or phase modulation constant 2 4 Couch, Digital and Analog Communication Systems, Seventh Edition ©2007 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. 0-13-142492-0 FM and PM FM and PM 5 7 Figure 5–9 FM with a sinusoidal baseband modulating signal. FM and PM differences PM: phase is proportional to m(t) θ (t) = Dpm(t) ⇒ FM: t θ (t) = D f m(α)dα ∫−∞ instantaneous frequency deviation from the fi (t) − fc = D f m(t) ⇒ carrier is proportional to m(t) radians Dp = K p ⇒ Modulation volt Constants Hz D f = K f ⇒ 6 volt 8 Couch, Digital and Analog Communication Systems, Seventh Edition ©2007 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. 0-13-142492-0 FM from PM FM and PM Signals PM from FM Maximum phase deviation in PM: Maximum frequency deviation in FM: 9 11 FM from PM Example PM from FM Let For PM For FM Define the modulation indices: 10 12 Example Spectrum Characteristics of FM Define the modulation indices: • FM/PM is exponential modulation Let φ(t) = β sin(2πfmt) u(t) = Ac cos(2πfct + β sin(2πfmt)) j(2πfct+β sin(2πfmt)) = Re()Ace u(t) is periodic in fm we may therefore use the Fourier series 13 15 Sine Wave Example Spectrum Characteristics of FM Then • FM/PM is exponential modulation c(t) = Ac cos(2πfct + β sin(2πfmt)) j(2πfct+β sin(2πfmt)) = Re()Ace c(t) is periodic in fm we may therefore use the Fourier series 14 16 Spectrum Characteristics with J Bessel Function Sinusoidal Modulation n u(t) is periodic in fm we may therefore use the Fourier series 17 19 Figure 5–11 Magnitude spectra for FM or PM with sinusoidal modulation for various modulation indexes.