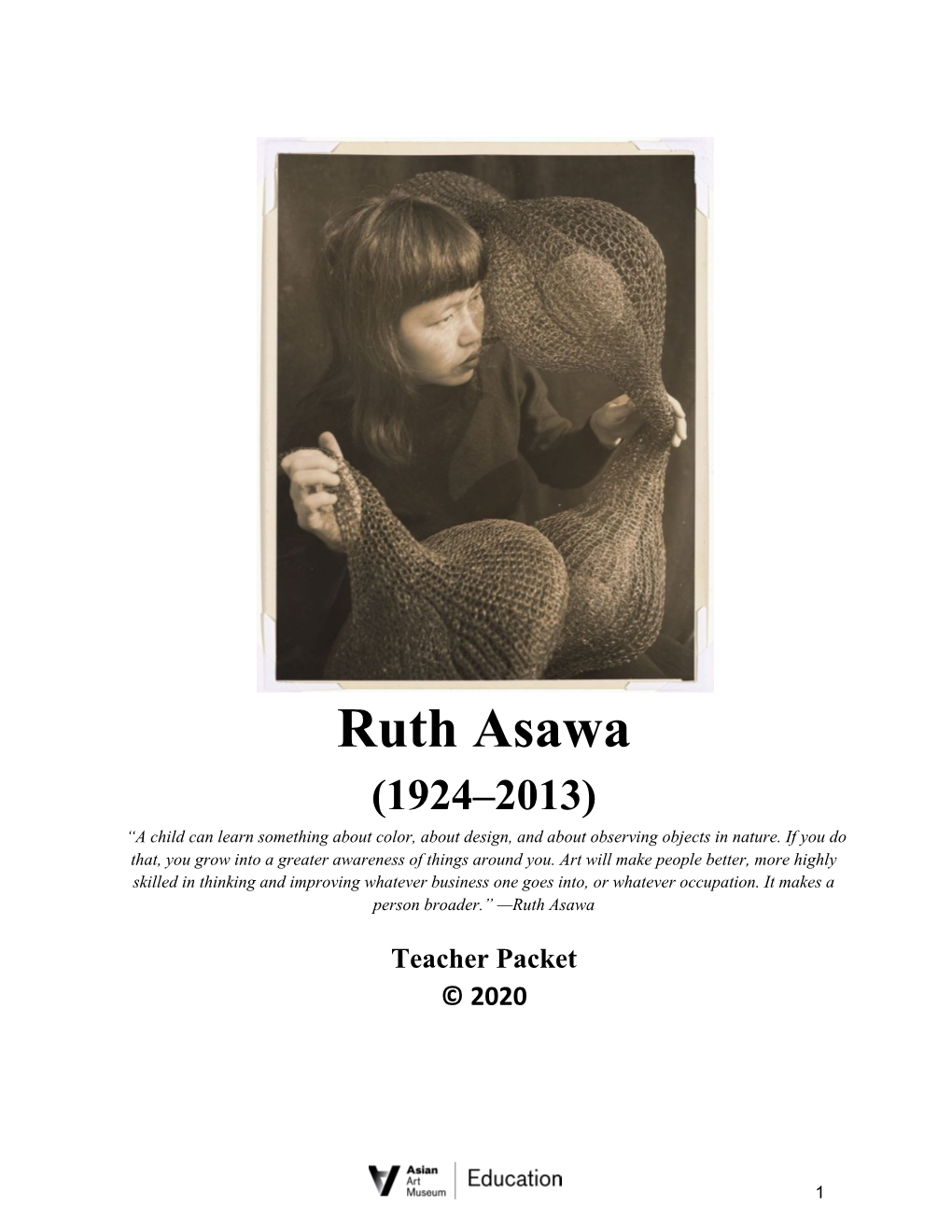

Ruth Asawa (1924–2013) “A Child Can Learn Something About Color, About Design, and About Observing Objects in Nature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rendering Rhythm and Motion in the Art of Black Mountain College

A Lasting Imprint Rendering Rhythm and Motion in the Art of Black Mountain College Movement and music—both time-based activities—can be difficult to express in static media such as painting, drawing, and photography, yet many visual artists feel called to explore them. Some are driven to devise new techniques or new combinations of media in order to capture or suggest movement. Similarly, some visual artists utilize elements found in music—rhythms, patterns, repetitions, and variations—to endow their compositions with new expressive potency. In few places did movement, music, visual arts, and myriad other disciplines intermingle with such profound effect as they did at Black Mountain College (BMC), an experiment in higher education in the mountains of Western North Carolina that existed from 1933 to 1957. For many artists, their introduction to interdisciplinarity at the college resulted in a continued curiosity around those ideas throughout their careers. The works in the exhibition, selected from the Asheville Art Museum’s Black Mountain College Collection, highlight approaches to rendering a lasting imprint of the ephemeral. Artists such as Barbara Morgan and Clemens Kalischer seek to capture the motion of the human form, evoking a sense of elongated or contracted muscles, or of limbs moving through space. Others, like Lorna Blaine Halper or Sewell Sillman, approach the challenge through abstraction, foregoing representation yet communicating an atmosphere of dynamic change. Marianne Preger-Simon’s drawings of her fellow dancers at BMC from summer 1953 are not only portraits but also a dance of pencil on paper, created in the spirit of BMC professor Josef Albers’s line studies as she simultaneously worked with choreographer Merce Cunningham. -

Ruth Asawa Bibliography

STANFORD UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES, DEPARTMENT OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS Ruth Asawa Bibliography Articles, periodicals, and other printed works in chronological order, 1948-2014, followed by bibliographic citations in alphabetical order by author, 1966-2013. Listing is based on clipping files in the Ruth Asawa papers, M1585. 1948 “Tomorrow’s Artists.” Time Magazine August 16, 1948. p.43-44 [Addison Gallery review] [photocopy only] 1952 “How Money Talks This Spring: Shortest Jacket-Longest Run For Your Money.” Vogue February 15, 1952 p.54 [fashion spread with wire sculpture props] [unknown article] Interiors March 1952. p.112-115 [citation only] Lavern Originals showroom brochure. Reprinted from Interiors, March 1952. Whitney Publications, Inc. Photographs of wire sculptures by Alexandre Georges and Joy A. Ross [brochure and clipping with note: “this is the one Stanley Jordan preferred.”] “Home Furnishings Keyed to ‘Fashion.’” New York Times June 17, 1952 [mentions “Alphabet” fabric design] [photocopy only] “Bedding Making High-Fashion News at Englander Quarters.” Retailing Daily June 23, 1952 [mentions “Alphabet” fabric design] [photocopy only] “Predesigned to Fit A Trend.” Living For Young Homemakers Vol.5 No.10 October 1952. p.148-159. With photographs of Asawa’s “Alphabet” fabric design on couch, chair, lamp, drapes, etc., and Graduated Circles design by Albert Lanier. All credited to designer Everett Brown “Living Around The Clock with Englander.” Englander advertisement. Living For Young Homemakers Vol.5 No.10 October 1952. p.28-29 [“The ‘Foldaway Deluxe’ bed comes only in Alphabet pattern, black and white.”] “What’s Ticking?” Golding Bros. Company, Inc. advertisement. Living For Young Homemakers Vol.5 No.10 October 1952. -

Get Smart with Art Is Made Possible with Support from the William K

From the Headlines About the Artist From the Artist Based on the critics’ comments, what aspects of Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902) is Germany in 1830, Albert Bierstadt Bierstadt’s paintings defined his popularity? best known for capturing majestic moved to Massachusetts when he western landscapes with his was a year old. He demonstrated an paintings of awe-inspiring mountain early interest in art and at the age The striking merit of Bierstadt in his treatment of ranges, vast canyons, and tumbling of twenty-one had his first exhibit Yosemite, as of other western landscapes, lies in his waterfalls. The sheer physical at the New England Art Union in power of grasping distances, handling wide spaces, beauty of the newly explored West Boston. After spending several years truthfully massing huge objects, and realizing splendid is evident in his paintings. Born in studying in Germany at the German atmospheric effects. The success with which he does Art Academy in Düsseldorf, Bierstadt this, and so reproduces the noblest aspects of grand returned to the United States. ALBERT BIERSTADT scenery, filling the mind of the spectator with the very (1830–1902) sentiment of the original, is the proof of his genius. A great adventurer with a pioneering California Spring, 1875 Oil on canvas, 54¼ x 84¼ in. There are others who are more literal, who realize details spirit, Bierstadt joined Frederick W. Lander’s Military Expeditionary Presented to the City and County of more carefully, who paint figures and animals better, San Francisco by Gordon Blanding force, traveling west on the overland who finish more smoothly; but none except Church, and 1941.6 he in a different manner, is so happy as Bierstadt in the wagon route from Saint Joseph, Watkins Yosemite Art Gallery, San Francisco. -

Making Their Mark 6

Making Their Mark 6 A CELEBRATION OF GREAT WOMEN ARTISTS Innovative sculptor Ruth Asawa (1926-2013) helped redefine mid-century American sculpture. The technique she first developed in the 1950s became her signature style: suspended, amorphous forms made from thousands of interconnected wire pieces. Born in Norwalk, California, Asawa was the daughter of Japanese immigrants who ran a truck farm. During World War II she, along with her mother and siblings (and thousands of other citizens of Japanese descent), were placed in an internment camp, first in a makeshift facility in California, then at the Rohwer War Relocation Center in Arkansas (her father was sent to a similar camp in New Mexico). Despite the injustice of her internment, Asawa harbored no resentment afterwards, instead maintaining that the experience helped shape her Ruth Asawa, Untitled, c.1960-63. Oxidized copper and Ruth Asawa in 1952, holding one of her wire pieces. identity. She used the eighteen months she spent in the brass wire, 94 x 17 1/2 x 17 1/2 inches. Photograph by Imogen Cunningham. © The Imogen camps to make art, after befriending a number of Disney Cunningham Trust. animators who had also been interred. Allowed to leave Rohwer in 1943, she attended college in Michigan, intending to become a teacher. An art class taken during a summer trip to Mexico, however, changed her life and career aspirations, and she enrolled at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. During its twenty-four years of existence , Black Mountain College offered hands-on instruction from a faculty roster that included Buckminster Fuller, Josef and Anni Albers, Jacob Lawrence, Willem de Kooning and John Cage. -

Ruth Asawa Born 1926 in Norwalk, California

This document was updated January 19, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Ruth Asawa Born 1926 in Norwalk, California. Died 2013 in San Francisco. EDUCATION 1943-1946 Milwaukee State Teachers College 1946-1949 Black Mountain College, North Carolina 1974 Honorary Doctorate, California College of Arts and Crafts 1997 Honorary Doctorate, San Francisco Art Institute 1998 Honorary Doctorate, San Francisco State University B.F.A. University of Wisconsin (formerly Milwaukee State Teachers College) SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1953 Ruth Asawa & Jean Varda, Tin Angel Nightclub, San Francisco [two-person exhibition] Ruth Asawa, Sillman & McNair Associates, New Haven, Connecticut Design Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts 1954 Ruth Asawa, Peridot Gallery, New York 1956 Ruth Asawa, Peridot Gallery, New York 1958 Ruth Asawa, Peridot Gallery, New York 1960 Ruth Asawa: Paintings, Drawings and Sculptures, M.H. de Young Memorial Museum, San Francisco 1962 Ruth Asawa and Arthur Secunda, Ankrum Gallery, Los Angeles [two-person exhibition] 1964 Ruth Asawa: Drawings and Sculpture, Shop 1, Rochester Institute of Technology, New York 1965 Ruth Asawa, Pasadena Museum of Art, California 1969 Recent Drawings: Ruth Asawa, Capper Gallery, San Francisco 1970 Sculpture: Ruth Asawa, San Marco Gallery, Dominican College, San Rafael, California 1973 Ruth Asawa: A Retrospective View, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art [catalogue] Ruth Asawa, Baxter Gallery, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena Ruth Asawa, Van Doren Gallery, San Francisco 1978 Ruth Asawa, Fresno Art Center, California 1979 Ruth Asawa, Cabrillo College, Aptos, California Ruth Asawa, Cedar Street Gallery, Santa Cruz Ruth Asawa, Santa Cruz County Building, California 1987 Ruth Asawa and Imogen Cunningham, Charles Campbell Gallery, San Francisco [two-person exhibition] 2001 Ruth Asawa: Completing the Circle, Fresno Art Museum, California [itinerary: Oakland Museum of California] 2003 Ruth Asawa: Sculptures, Drawings, Lithographs, Tobey C. -

Rendering Rhythm and Motion in the Art Of

A Lasting Imprint Rendering Rhythm and Motion in the Art of Black Mountain College Movement and music—both time-based activities—can be difficult to express in static media such as painting, drawing, and photography, yet many visual artists feel called to explore them. Some are driven to devise new techniques or new combinations of media in order to capture or suggest movement. Similarly, some visual artists utilize elements found in music—rhythms, patterns, repetitions, and variations—to endow their compositions with new expressive potency. In few places did movement, music, visual arts, and myriad other disciplines intermingle with such profound effect as they did at Black Mountain College (BMC), an experiment in higher education in the mountains of Western North Carolina that existed from 1933 to 1957. For many artists, their introduction to interdisciplinarity at the college resulted in a continued curiosity around those ideas throughout their careers. The works in the exhibition, selected from the Asheville Art Museum’s Black Mountain College Collection, highlight approaches to rendering a lasting imprint of the ephemeral. Artists such as Barbara Morgan and Clemens Kalischer seek to capture the motion of the human form, evoking a sense of elongated or contracted muscles, or of limbs moving through space. Others, like Lorna Blaine Halper or Sewell Sillman, approach the challenge through abstraction, foregoing representation yet communicating an atmosphere of dynamic change. Marianne Preger-Simon’s drawings of her fellow dancers at BMC from summer 1953 are not only portraits but also a dance of pencil on paper, created in the spirit of BMC professor Josef Albers’s line studies as she simultaneously worked with choreographer Merce Cunningham. -

Proquest Dissertations

RICE UNIVERSITY The Internment of Memory: Forgetting and Remembering the Japanese American World War II Experience by Abbie Lynn Salyers A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE: Ira Gruber, Harris Masterson Jr. Professor Chair, History hOv^L Lora Wildenthal, Associate Professor History Richard Stolli Kiofessor Political Science! HOUSTON, TEXAS MAY 2009 UMI Number: 3362399 Copyright 2009 by Salyers, Abbie Lynn INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform 3362399 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Copyright Abbie Lynn Salyers 2009 ABSTRACT The Internment of Memory: Forgetting and Remembering the Japanese American Experience During World War II by Abbie Salyers During World War II, over 100,000 Japanese American were confined in relocation and internment camps across the country as a result of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066. While many of their families were behind barbed wire, thousands of other Japanese Americans served in the US Army's Military Intelligence Service and the all-Japanese American 100th Infantry and 442nd Regimental Combat Team. -

David Zwirner New York, NY 10021 Telephone 212 517 8677

34 East 69th Street Fax 212 517 8959 David Zwirner New York, NY 10021 Telephone 212 517 8677 For immediate release JOSEF AND ANNI AND RUTH AND RAY September 20 – October 28, 2017 Special event: Guided tour with Nicholas Fox Weber, Executive Director, The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation: Saturday, October 28, 11 AM David Zwirner is pleased to present Josef and Anni and Ruth and Ray as the inaugural exhibition at the gallery’s 34 East 69th Street location. Featuring work by Josef Albers, Anni Albers, Ruth Asawa, and Ray Johnson—all of whom were at Black Mountain College in North Carolina in the late 1940s—this exhibition will explore both the aesthetic and personal dialogue between these artists during their Black Mountain years and beyond; and will include a number of works exchanged amongst the group, in addition to a selection of key compositions influenced by their time there. Josef and Anni Albers arrived at Black Mountain College in 1933, both having studied and subsequently taught at the Bauhaus for nearly a decade. It was through the Alberses that the pedagogy of the famed German art school, which espoused ideals of radical experimentation and an open interchange of ideas, was imported and adapted in their new setting. As Asawa recalls, Josef Albers would open his Basic Design course by saying, “Open your eyes and see. My aim is to make you see more than you want to. I am here to destroy your prejudices. If you already have a style don’t bring it with you. It will only be in the way”¹ —in essence paraphrasing the aesthetic philosophy that came to define Black Mountain College as a progressive and avant-garde Josef Albers institution in those years. -

BROAD STROKES 15 WOMEN WHO MADE ART and MADE HISTORY (IN THAT ORDER)

BROAD STROKES 15 WOMEN WHO MADE ART and MADE HISTORY (IN THAT ORDER) BY BRIDGET QUINN WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY LISA CONGDON 11/16/16 2:25 PM BroadStrokes_INT_1stPrf.indd 18-19 Artemisia Gentileschi. Judith Severing the Head of Holofernes. c. 1620. 20 BroadStrokes_INT_1stPrf.indd 20-21 Florence after the birth of her children. She may have felt it suited Medici taste, with its high drama, opulence, and violence. Or maybe given her reputation, there was interest in a scene of implied revenge. I’d like to kill you with this knife because you have dishonoured me. Tassi had dark hair, and also a beard. * * * * * If it is difficult to look at Caravaggio’s full-lipped young men and not feel a sexual undercurrent (he may have been gay), then the case for reading a biographical urge into Artemisia’s work is even more tempting. A young woman experiences rape followed by public torture and humiliation. Shortly after- Artemisia Gentileschi. Susanna and the Elders. 1610. ward, she paints her first version of a scene John Ruskin thought Botticelli’s version by depicting a woman decapitating a bearded man. far the best of a terrible tradition. If you But Artemisia was hardly the first artist don’t know Ruskin, he was a voluminous to depict the story of Judith. It was long a Victorian critic whose influence was vast. popular theme. Caravaggio has a famous (I can’t resist this take on him from a New version, with a more typical Judith as a York Times review of the Mike Leigh film, lovely young thing (complete with erect Mr. -

Oral History Interview with Ruth Asawa and Albert Lanier

Oral history interview with Ruth Asawa and Albert Lanier Funding for the transcription of this interview provided by the San Francisco Foundation/Jacqueline Hoefer Fund. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 General............................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Oral history interview with Ruth Asawa and Albert Lanier -

Chapter 5 Love Letters

Excerpt from: Everything She Touched: The Life of Ruth Asawa by Marilyn Chase, published by Chronicle Books 2020 https://www.chroniclebooks.com/collections/art-design/products/everything-she-touched Chapter 5 Love Letters Albert Lanier’s Model A jalopy was holding up and getting good gas mileage. “It’s the strangest looking car ever,” he wrote to his parents in Georgia. “Children run out and wave and flock around us wherever we stop.” To avoid the heat, Albert and his friends slept during the day and drove at night on their way from Black Mountain College in North Carolina to San Francisco. When they ran low on funds near the end of the trip, Albert resorted to selling his blood in Las Vegas. Tired from the procedure, he slept and awoke to find his traveling companions fresh from a gambling spree and sporting new shirts bought with his “blood money.” They had barely enough for the bridge toll across San Francisco Bay. He’d laugh about it later. By September, Albert moved in with his Black Mountain friends “Rags” Watkins and Peggy Tolk- Watkins. Peggy had drawn Albert to the City by the Bay with tales of a bohemian good life, where young artists could dine on a four-course Italian dinner with red wine for seventy-five cents. Reality didn’t quite live up to the romance. Albert took work as a carpenter’s apprentice for union wages. Torn between staying at Black Mountain and helping her family resettle, Ruth Asawa took a short leave from art school in September and October of 1948 to lend a hand on their new farm near Los Angeles. -

Ruth Asawa: Citizen of the Universe Modern Art Oxford: 12 February - 9 May 2021

§- Ruth Asawa: Citizen of the Universe Modern Art Oxford: 12 February - 9 May 2021 Ruth Asawa, 1957. Photo by Imogen Cunningham. © 2020 Imogen Cunningham Trust. Artwork © Estate of Ruth Asawa, Courtesy David Zwirner Oxford, UK: Citizen of the Universe is the first public solo exhibition in Europe of the work of Ruth Asawa (b. 1926, Norwalk, CA – d. 2013, San Francisco, CA). Focusing on a dynamic formative period in her life from 1945 to 1980, the exhibition gives audiences a unique experience of the artist and her work, exploring her legacy as an abstract sculptor crucial to modernism in the United States. The exhibition features her signature hanging sculptures in looped and tied wire and celebrates her holistic integration of art, education and community engagement, through which she called for an inclusive and revolutionary vision for art’s role in society. Running parallel with the creation of her acclaimed sculptures Asawa was committed to arts education. This aspect of her practice will be explored in the exhibition through a selection of her drawing and printmaking, as well as archival materials displaying her work as an arts activist for professional artists working in state schools. Key projects include her Milk Carton Sculptures which encourage children to playfully interrogate found materials to deepen their understanding of abstract mathematical thinking. Asawa was ardently committed to art education’s role in transforming and empowering both adults and children, and was dedicated to giving children the opportunity to work directly with professional artists. Her lifelong philosophy of the “integration of creative labour within daily life” was nurtured during her studies in the progressive educational environment of Black Mountain College from 1946-49.