AUTHOR TITLE Students ABSTRACT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National FUTURE FARMER, Insurance Company 14 Columbus Cycle Company

The National Futuie Farmer Owned and Published by the Future Farmers of America Livestock Judging—Where skills are tested! October -November, 1960 In This issue: • Corner Your Fencing Problems • Mechanizing iVIanagement o A Farm Visit With Your Vice Presidents • How Would You Vote? ip X :>--f-"%.^<^' Doors are double-sealed against weather, cabs seat three passengers comfort- ably. Standard V-8 engines are true-truck designed . plenty of power for pulling, passing or any purpose. Specialized highway units transport any farm com- modity with dependable gas, diesel or LPG power. For family pleasure ...farm profit! International Trucks arc still ready to go, even when a full day's work is done. You'll find they're styled for easier, safer driving, across country and through town. Wide, fully-adjustable seat and more glass front and rear make this .so. These hard-working models range from INTERNATIONAE pickups with standard or Bonus-Load bodies to husky road haulers that handle big loads at least cost. So see your International Dealer TRUCKS or Internalional Harvester Co Branch now to learn how . ChicaRO International Motor Trucks • Crawler Tractors Construction • 5 Tnicks s i\ (' you money on every job. Equipment McCormick Farm Equipment ant] Farmall'i^ Tractors WORLD'S MOST COMPLETE LINE Raymond Hetherington. Ringtown, Pennsylvania Farmers you look to as leaders look to Firestone for farm tires Mountains and ridges in the heart of the Pennsylvania coal country are laced with level valleys. In Schuylkill County's Ringtown Valley, modern methods and irrigation help Raymond Hetherington wrest high yields of quality vegetables and other crops. -

The Book of Three Free Ebook

FREETHE BOOK OF THREE EBOOK Lloyd Alexander | 190 pages | 16 May 2006 | Henry Holt & Company | 9780805080483 | English | New York, NY, United States “The Book of Three” at Usborne Children’s Books Taran is desperate The Book of Three adventure. Being a lowly Assistant Pig-Keeper just isn't exciting. That is, until the magical pig, Hen Wen, disappears and Taran embarks on a death-defying quest to save her from the evil Horned King. His perilous adventures bring Taran many new friends: an irritable dwarf, an impulsive bard, a strange hairy beast and the hot-headed Princess Eilonwy. Together, they face many dangers, from the deathless Cauldron-Born warriors, dragons, witches and the terrifying Horned King himself. Taran learns much about his identity, but the mysterious Book of Three is yet to reveal his true destiny. He was reading by the time he was 3, and though he did poorly in school, at the age of fifteen, he announced that he wanted to become a writer. Alexander served in the Intelligence Department, stationed in Wales, and then went on to Counter-Intelligence in Paris, where he was promoted to Staff Sergeant. When the war ended in '45, Alexander applied to the Sorbonne, but returned to the States in '46, now married. Alexander worked as an unpublished The Book of Three for seven years, accepting positions such as cartoonist, advertising copywriter, layout artist, and The Book of Three editor for a small magazine. Directly after the war, he had translated works for such artists as Jean Paul Sartre. In"And Let the Credit Go" was published, The Book of Three first book which led to 10 years of writing for an adult audience. -

Not Another Trash Tournament Written by Eliza Grames, Melanie Keating, Virginia Ruiz, Joe Nutter, and Rhea Nelson

Not Another Trash Tournament Written by Eliza Grames, Melanie Keating, Virginia Ruiz, Joe Nutter, and Rhea Nelson PACKET ONE 1. This character’s coach says that although it “takes all kinds to build a freeway” he is not equipped for this character’s kind of weirdness close the playoffs. This character lost his virginity to the homecoming queen and the prom queen at the same time and says he’ll be(*) “scoring more than baskets” at an away game and ends up in a teacher’s room wearing a thong which inspires the entire basketball team to start wearing them at practice. When Carrie brags about dating this character, Heather, played by Ashanti, hits her in the back of the head with a volleyball before Brittany Snow’s character breaks up the fight. Four girls team up to get back at this high school basketball star for dating all of them at once. For 10 points, name this character who “must die.” ANSWER: John Tucker [accept either] 2. The hosts of this series that premiered in 2003 once crafted a combat robot named Blendo, and one of those men served as a guest judge on the 2016 season of BattleBots. After accidentally shooting a penny into a fluorescent light on one episode of this show, its cast had to be evacuated due to mercury vapor. On a “Viewers’ Special” episode of this show, its hosts(*) attempted to sneeze with their eyes open, before firing cigarette butts from a rifle. This show’s hosts produced the short-lived series Unchained Reaction, which also aired on the Discovery Channel. -

Embeddings for KB and Text Representation, Extraction and Question Answering

Embeddings for multi-relational data Pros and cons of embedding models Embeddings for KB and text representation, extraction and question answering. Jason Westony & Antoine Bordes & Sumit Chopra Facebook AI Research External Collaborators: Alberto Garcia-Duran & Nicolas Usunier & Oksana Yakhnenko y Some of this work was done while J. Weston worked at Google. 1 / 24 Embeddings for multi-relational data Pros and cons of embedding models Multi-relational data Data is structured as a graph Each node = an entity Each edge=a relation/fact A relation = (sub, rel, obj): sub =subject, rel = relation type, obj = object. Nodes w/o features. We want to also link this to text!! 2 / 24 Embeddings for multi-relational data Pros and cons of embedding models Embedding Models KBs are hard to manipulate Large dimensions: 105=108 entities, 104=106 rel. types Sparse: few valid links Noisy/incomplete: missing/wrong relations/entities Two main components: 1 Learn low-dimensional vectors for words and KB entities and relations. 2 Stochastic gradient based training, directly trained to define a similarity criterion of interest. 3 / 24 Embeddings for multi-relational data Pros and cons of embedding models Link Prediction Add new facts without requiring extra knowledge From known information, assess the validity of an unknown fact Goal: We want to model, from data, P[relk (subi ; objj ) = 1] ! collective classification ! towards reasoning in embedding spaces 4 / 24 Embeddings for multi-relational data Pros and cons of embedding models Previous Work Tensor factorization -

Blackcauldron-Manual

- Lloyd Alexander blends the rich elements of Welsh legend and universal mythology in his five-volume fantasy epic "The Chronicles of Prydain." . " ... considered to be the most significant fantasy cycle created for children today by an American author." -- from the citation to The High King for the Newbery Medal given annually by the American Library Association for " the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children. " The Chronicles of Prydain by Lloyd Alexander: The Book of Three The Black Cauldron The Castle of Llyr Taran Wanderer The High King Other Prydain books by Lloyd Alexander: The Foundling, and Other Tales of Prydain Coll and His White Pig The Truthful Harp Portions of this manual are condensed or exc~rpted from: The Book of Three, © 1964 by Lloyd Alexander The High King , © 1968 by Lloyd Alexander The Foundling, and Other Tales of Prydain, © 1973 by Lloyd Alexander The Black Cauldron, an all-animated feature, © Walt Disney Productions MCMLXXXV DALLBEN AND THE BOOK OF THREE hen he was just a baby, Dallben, greatest of enchanters in all Prydai n , was abandoned in a wicker basket at the edge of the Marshes of Morva. There he was found by three witches, Orddu, Orwen and Orgoch, and was taken to live with them in their home at the center of the marsh. As he grew, Dallben watched the witches in all they did, and learned their powers of enchantment. On the day he left them to make a life for himself, they made him a present of an ancient volume entitled The Book of Three. -

2018 Issued BL 11192018 by DATE

2018 Issued Tukwila Business Licenses Sorted by Date of Application DBA Name Full Name Full Primary Address UBC # NAICS Creation NAICS Description Code Date TROYS ELECTRIC EDWARDS TROY A 2308 S L ST 602712157 238210 11/13/2018 Electrical Contractors TACOMA WA 98405 and Oth OLD MACK LLC OLD MACK LLC 2063 RYAN RD 604216260 423320 11/13/2018 Brick, Stone, and BUCKLEY WA 98321 Related Cons DRAGONS BREATH CREAMERY NITRO SNACK LLC 1027 SOUTHCENTER MALL 604290130 445299 11/9/2018 All Other Specialty Food TUKWILA WA 98188 Store NASH ELECTRIC LLC NASH ELECTRIC LLC 8316 71ST ST NE 603493097 238210 11/8/2018 Electrical Contractors MARYSVILLE WA 98270 and Oth BUDGET WIRING BUDGET WIRING 12612 23RD AVE S 601322435 238210 11/7/2018 Electrical Contractors BURIEN WA 98168 and Oth MATRIX ELECTRIC LLC MATRIX ELECTRIC LLC 15419 24TH AVE E 603032786 238210 11/7/2018 Electrical Contractors TACOMA WA 98445-4711 and Oth SOUNDBUILT HOMES LLC SOUNDBUILT HOMES LLC 12815 CANYON RD E 602883361 236115 11/7/2018 General Contractor M PUYALLUP WA 98373 1ST FIRE SOLUTIONS LLC 1ST FIRE SOLUTIONS LLC 4210 AUBURN WAY N 603380886 238220 11/6/2018 Plumbing, Heating, and 7 Air-Con AUBURN WA 98002 BJ'S CONSTRUCTION & BJ'S CONSTRUCTION & 609 26TH ST SE 601930579 236115 11/6/2018 General Contractor LANDSCAPING LANDSCAPING AUBURN WA 98002 CONSTRUCTION BROKERS INC CONSTRUCTION BROKERS INC 3500 DR GREAVES RD 604200594 236115 11/6/2018 General Contractor GRANDVIEW MO 64030 OBEC CONSULTING ENGINEERS OBEC CONSULTING ENGINEERS 4041 B ST 604305691 541330 11/6/2018 Engineering Services -

Winning ""Chronicles of Prydain""1 Is Now a Thret'-Dimt-Nsioniil Qpwnated Adventure ^Aute

The Walt Disney^ inductions movie, based on novelist Mayd Alexander's Newbery A ward- winning ""Chronicles of Prydain""1 is now a thret'-dimt-nsioniil qpwnated adventure ^aute... Lloyd Alexander blends the rich elements of Welsh legend and universal mythology in his five-volume fantasy epic "The Chronicles of Prydain." "...considered to be the most significant fantasy cycle created for children today by an American author." — from the citation to The High King for the Newbery Medal given annually by the American Library Association for "the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children." The Chronicles of Prydain by Lloyd Alexander; The Book of Three The Black Cauldron The Castle of Llyr Taran Wanderer The High King Other Prydain books by Lloyd Alexander: The Foundling, and Other Tales of Prydain Coll and His White Pig The Truthful Harp Portions of ihis manual arc condensed or excerpted from: The Book of Three, © 1964 by Lloyd Alexander The High King. '£.• 1%8 by Lloyd Alexander The Foundling, and Other Talcs of Prydain. © 1973 by Lloyd Alexander The Black Cauldron, an all-animated feature, ict Wall Disney Productions MCMLXXXV DALLBEN AND THE BOOK OF THREE hen he was just a baby, Dallben, greatest of enchanters in all Prydain, was abandoned in a wicker basket at the edge of the Marshes of Morva. There he was found by three witches, Orddu, Orwen and Orgoch, and was taken to live with them in their home at the center of the marsh. m As he grew, Dallben watched the witches in all they did, and learned their powers of enchantment. -

Gettysburg National Military Park STUDENT PROGRAM

Gettysburg National Military Park STUDENT PROGRAM 1 Teachers’ Guide Table of Contents Purpose and Procedure ...................................3 FYI ...BackgroundInformationforTeachersandStudents CausesoftheAmericanCivilWar .........................5 TheBattleofGettysburg .................................8 CivilWarMedicalVocabulary ...........................12 MedicalTimeline ......................................14 Before Your Field Trip The Oath of Allegiance and the Hippocratic Oath ...........18 Squad #1 Activities — Camp Doctors .....................19 FieldTripIdentities .........................20 "SickCall"Play..............................21 CampDoctorsStudyMaterials ................23 PicturePages ...............................25 Camp Report — SickCallRegister .............26 Squad #2 Activities — BattlefieldDoctors .................27 FieldTripIdentities .........................28 "Triage"Play ...............................29 BattlefieldStudyMaterials ...................30 Battle Report — FieldHospitalRegister ........32 Squad #3 Activities — HospitalDoctors ...................33 FieldTripIdentities .........................34 "Hospital"Play..............................35 HospitalStudyMaterials(withPicturePages) ...37 Hospital Report — CertificateofDisability .....42 Your Field Trip Day FieldTripDayProcedures ..............................43 OverviewoftheFieldTrip ..............................44 Nametags .............................................45 After Your Field Trip SuggestedPost-VisitActivities ...........................46 -

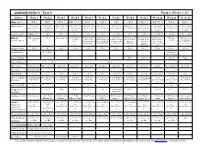

Year 8 Term 1 (Weeks 1-12) Subject Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 Week 5 Week 6 Week 7 Week 8 Week 9 Week 10 Week 11 Week 12

AmblesideOnline's - Year 8 Term 1 (Weeks 1-12) Subject Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 Week 5 Week 6 Week 7 Week 8 Week 9 Week 10 Week 11 Week 12 Bible New T Matt 1 Matt 2 Matt 3, 4 Matt 4:18-5:16 Matt 5:17-48 Matt 6 Matt 7 Matt 8 Matt 9:1-17 Matt 9:18-38 Matt 10 Matt 11 Old testament Jud 1-3; Ps Jud 4-6; Ps Jud 7-9:21; Ps Jud 9:22-11; Ps Jud 12-15; Ps Jud 16-18; Ps Jud 19-21; Ps Ruth; Ps 112, 1Sam 1-3; Ps 1Sam 4-8; Ps 1Sam 9-12; Ps 1Sam 13, 14; Ps 106:1-23; Pr 1:1- 106:24-48; Pr 107:1-22; Pr 2:1- 107:23-43; Pr 108; Pr 3:1-20 109; Pr 3:21-35 110, 111; Pr 4:1- 113; Pr 4:14-27 114, 115; Pr 5:1- 116, 117; Pr 118:1-18; Pr 6:1- 118:19-29; Pr 19 1:20-33 9 2:10-22 3 14 5:15-23 19 6:20-35 Case for Christ Intro, Ch 1 Ch 2 Ch 3 Ch 4 Ch 5 Ch 6 Ch 7&8 Ch 9 Ch 10 Ch 11&12 Ch 13 Ch 14 - end History Ch 1 Columbus, Ch 2 Ch 3 Henry VIII ch 4 to page 49, end of ch 4 and first second half of ch 5 from "In the first half of ch 7 to second half of ch 7 second half of ch 8 Ch 9 Drake, Ch 10 1588, Sir Luther "On October 9, half of ch 5 to and beginning of ch Autumn, when the page 97, "Catholic to middle of ch 8 from "meanwhile, Armada Walter Raleigh, The New World 1529. -

The Book of Three by Lloyd Alexander

Teacher Guide The Book of Three by Lloyd Alexander Questions for Socratic Discussion by Melanie Huff © 2012, The Center for Literary Education 3350 Beck Road Rice, WA 99167 (509) 738-2837 www.centerforlit.com Contents Introduction 2 Questions about Structure: Setting 4 Questions about Structure: Characters 6 Questions about Structure: Conflict and Plot 11 Questions about Structure: Theme 14 Questions about Style 16 Questions about Context 18 Suggested Essay Assignments 19 Story Charts 20 Introduction This teacher guide is intended to assist the teacher or parent in conducting meaningful discussions of literature in the classroom or home school. Questions and answers follow the pattern presented in Teaching the Classics, the Center for Literary Education’s two day literature seminar. Though the concepts underlying this approach to literary analysis are explained in detail in that seminar, the following brief summary presents the basic principles upon which this guide is based. The Teaching the Classics approach to literary analysis and interpretation is built around three unique ideas which, when combined, produce a powerful instrument for understanding and teaching literature: First: All works of fiction share the same basic elements — Context, Structure, and Style. A literature lesson that helps the student identify these elements in a story prepares him for meaningful discussion of the story’s themes. Context encompasses all of the details of time and place surrounding the writing of a story, including the personal life of the author as well as historical events that shaped the author’s world. Structure includes the essential building blocks that make up a story, and that all stories have in common: Conflict, Plot (which includes exposition, rising action, climax, denouement, and conclusion), Setting, Characters and Theme. -

Lloyd Alexander's the Book of Three

Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three: A Discussion Guide By David Bruce SMASHWORDS EDITION Copyright 2008 by Bruce D. Bruce Thank you for downloading this free ebook. You are welcome to share it with your friends. This book may be reproduced, copied and distributed for non-commercial purposes, provided the book remains in its complete original form. If you enjoyed this book, please return to Smashwords.com to discover other works by this author. Thank you for your support. Dedicated with Love to Caleb Bruce ••• Preface The purpose of this book is educational. I enjoy reading Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three, and I believe that it is an excellent book for children (and for adults such as myself) to read. This book contains many questions about Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three and their answers. I hope that teachers of children will find it useful as a guide for discussions. It can also be used for short writing assignments. Students can answer selected questions from this little guide orally or in one or more paragraphs. I hope to encourage teachers to teach Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three, and I hope to lessen the time needed for teachers to prepare to teach this book. This book uses many short quotations from Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three. This use is consistent with fair use: § 107. Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair use Release date: 2004-04-30 Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. -

Lloyd Alexander 30

Der phantastische Autorenbrief Lloyd Alexander 30. 01. 1924 - 17. 05. 2007 Mai 2007 unabhängig kostenlos Ausgabe 441 Lloyd Chudley Alexander starb am 17.05.2007 im Alter von 83 Jahren. Er wurde am 30. Januar 1924 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Vereinigte Staaten von Amerika geboren, wuchs dort auf und lebte dort bis zu seinem Tod. Bereits mit drei Jahren lernte er lesen und interessierte sich seither für Bücher. Später erweiterte er sein Interesse auf klassische Musik und Zeichnen. Besonders angetan hatten es ihm die keltische und griechische Mythologie, die auch in seinen eigenen Werken ihren Niederschlag fanden. Wie bei vielen seiner Altersklasse war ein Buch über den sagenhaften König Arthus und die dazu gehörigen Heldensagen für ihn Meinungs bildend. Neben diesen Sagen beschäftigte er sich mit den Mabinogin, jener Sammlung klassischer walisischer Sagen, die später so viel Einfluss auf ihn ausübten. Nach seinem Highschool-Abschluss und einer kurzen Episode als Laufbursche bei einer Bank besuchte er das örtliche College. Bereits nach dem ersten Trimester verließ er das College und trat in die US-Army ein. Er wurde zuerst nach Wales zum militärischen Geheimdienst (Army Combat Intelligenz) versetzt, wo er wieder auf keltische und walisische Mythen traf. Lloyd Alexander, der neben spanisch und französisch sich im Selbststudium walisisch beibrachte, konnte so die Schauplätze seiner Heldensagen selbst besuchen. Die Kenntnisse seines Dialektes öffnete ihm in Wales viele Tore, so dass er seine Studien über diese Sagenwelt weiter vorantreiben konnte. Viele dieser Eindrücke verarbeitete er in seinen Büchern. Anfang 1945 wurde er nach Paris versetzt, wo er in der Gegenspionage arbeitete. Nach dem Krieg besuchte er die Universität von Paris.