ED352549.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vs. SOUTH CAROLINA (13-12, 4-8 SEC) OVERALL RECORD: 18-6 FEB

GAME #25 10 SEC CHAMPIONSHIPS | 25 ALL-AMERICANS | 11 SEC PLAYERS OF THE YEAR | 46 NBA DRAFT PICKS #18/#17 TENNESSEE (18-6, 8-4 SEC) 2017-18 » SCHEDULE & RECORD vs. SOUTH CAROLINA (13-12, 4-8 SEC) OVERALL RECORD: 18-6 FEB. 13 » THOMPSON-BOLING ARENA » KNOXVILLE, TENN. » 9:05 PM ET SEC 8-4 NON-CONFERENCE 10-2 THE MATCHUP HOME 10-2 AWAY 6-3 TENNESSEE VOLUNTEERS SOUTH CAROLINA GAMECOCKS vs NEUTRAL 2-1 THE RECORD QUICK COMPARISON 75.9 ppg Points Per Game 69.0 ppg THE SCHEDULE 67.2 ppg Points Allowed Per Game 67.9 ppg DATE OPPONENT (TV) TIME/RESULT 36.4 rpg Rebounding Per Game 37.0 rpg N10 Presbyterian (SEC Network+) W, 88-53 34.4 rpg Rebounding Defense 33.0 rpg N14 High Point (SEC Network+) W, 84-53 N22 1-vs. #18 Purdue (ESPN2) W, 78-75 (OT) .445 Field Goal Pct. .395 N23 1-vs. #5 Villanova (ESPN) L, 85-76 .386 3-Point Pct. .320 UTSPORTS.COM GAMECOCKSONLINE.COM N24 1- vs. NC State (ESPN2) W, 67-58 N29 Mercer (SEC Network+) W, 84-60 TENNESSEE QUICK FACTS SOUTH CAROLINA QUICK FACTS Head Coach: Rick Barnes (Lenoir-Rhyne, 1977) Head Coach: Frank Martin (FIU, 1993) D3 at Georgia Tech (ESPNU) W, 77-70 Record at Tennessee: 49-41 / 3rd year Record at South Carolina: 109-86 / 6th year D9 Lispcomb (SEC Network) W, 81-71 D17 #7 North Carolina (ESPN) L 78-73 Career Record: 653-355 / 31st year Career Record: 226-140 / 11th year D20 Furman (SEC Network) W, 66-61 Scoring Leader: Grant Williams (15.9 ppg, 9th in SEC) Scoring Leader: Chris Silva (14.3 ppg, 15th in SEC) D23 at Wake Forest (ESPN2) W, 79-60 Rebounds Leader: Admiral Schofield (6.3 rpg, 12th in SEC) Rebounds Leader: Chris Silva (7.6 rpg, 4th in SEC) D30 at Arkansas* (SEC Network) L, 95-93 (OT) Assists Leaders: Jordan Bone and James Daniel III (3.5 apg) Assists Leader: Hassani Gravett (3.5 apg) J2 Auburn* (ESPNU) L, 94-84 J6 #17 Kentucky* (ESEC Network) W, 76-65 J9 at Vanderbilt* (SEC Network) W, 92-84 VOLS EAGER TO PUT POOR SHOWING AT BAMA IN REAR-VIEW J13 Texas A&M* (SEC Network) W, 75-62 J17 at Missouri* (SEC Network) L, 59-55 J20 at South Carolina* (ESPN2) W, 70-63 THE SERIES RIGHT NOW A WIN WOULD.. -

Utsports.Com » @Vol Hoops 9 Outl Ook Players S Taff

OUTLOOK PLAYERS STAFF REVIEW RESULTS RECORDS HONORS POSTSEASON VOLMANAC MEDIA INFO 9 Tennessee’s roster roster Tennessee’s this season blends scholarship seven with returners scholarship five newcomers. @VOL_HOOPS » UTSPORTS.COM KYLE ALEXANDER SENIOR 11 Forward • 6-11 • 215 Milton, Ontario, Canada Orangeville Prep Post-Graduate Studies KYLE al-ick-ZAN-duhr Total 3-pt Year GP-GS Min Avg FG-FGA Pct FG-FGA Pct FT-FTA Pct Rebs Avg PF-DQ Ast TO Blk Stl Pts Avg 15-16 32-11 391 12.2 16-37 .432 0-0 .000 21-32 .656 101 3.2 55-0 2 14 31 5 53 1.7 16-17 32-23 447 14.0 41-88 .466 1-6 .167 22-44 .500 129 4.0 53-0 6 15 33 6 105 3.3 17-18 34-34 690 20.3 77-113 .681 1-1 1.000 37-52 .712 189 5.6 83-3 11 25 57 19 192 5.6 TOTAL 98-68 1528 15.6 134-238 .563 2-7 .286 80-128 .625 419 4.3 191-3 19 54 121 30 350 3.6 2017-18 - JUNIOR • Completed the requirements for his bachelor’s degree in May (Bachelor of Arts in Communication with a major in Communication Studies). • Started all 34 games in which he appeared and posted career-highs in virtually every statistical category. • Etched his name in UT’s single-season records for blocks (4th) with 57 and ofensive rebounds (11th) with 85. • Among Division I players averaging at least two field-goal attempts per game, his shooting percentage of .679 ranked 18th in the nation. -

SENATE JOINT RESOLUTIONS House Journal – 2019-2020 1

SENATE JOINT RESOLUTIONS House Journal – 2019-2020 Description Other Action Number Speaker Signed by by Signed Committee Referred to Referred Transmitted Concurred in Concurred 1 Constitutional Amendments - Proposes amendment to Article VI, Section 5 to provide for 598 599 1470 1707 883, 1068, 1070, 1205, 1255, 1470, the selection of the attorney general and reporter for the state with nomination by the 1707 supreme court and confirmation by the general assembly. 4 Memorials, Professional Achievement - Sheriff Jeff Bledsoe, Tennessee Sheriff of the 59 112 145 63, 140 Year 5 Memorials, Death - Charles E. McNeeley 59 112 145 63, 140 6 Memorials, Death - Willard Lacy Upchurch 59 112 145 63, 115, 140 7 Memorials, Death - Virginia "Ginny" Edwards 59 112 145 63, 140 8 Memorials, Death - Floyd Thomas Nelson 59 112 145 63, 140 9 Memorials, Recognition - Emeline Thrash Dunn, 2019 Nashville's Top 30 Under 30 59 113 145 63, 140 10 Memorials, Recognition - Rebecca Sheaffer Goodwin, 2019 Nashville's Top 30 Under 30 59 113 145 63, 140 11 Memorials, Recognition - Casey L. Miller, 2019 Nashville's Top 30 Under 30 59 113 145 63, 140 12 Memorials, Recognition - Alé Dalton, 2019 Nashville's Top 30 Under 30 59 113 145 63, 140 13 Memorials, Recognition - Adelee Traylor Seidel, 2019 Nashville's Top 30 Under 30 59 113 145 63, 140 14 Memorials, Recognition - Nora Snoddy, 2019 Nashville's Top 30 Under 30 59 113 145 64, 140 15 Memorials, Recognition - Susan E. Pogue, 2019 Nashville's Top 30 Under 30 59 113 145 64, 140 16 Memorials, Recognition - Pirjin Tayip Laser, -

15/#14 TENNESSEE (17-5, 7-3 SEC) 2017-18 » SCHEDULE & RECORD at #24/#24 KENTUCKY (17-6, 6-4 SEC) OVERALL RECORD: 17-5 FEB

GAME #23 10 SEC CHAMPIONSHIPS | 25 ALL-AMERICANS | 11 SEC PLAYERS OF THE YEAR | 46 NBA DRAFT PICKS #15/#14 TENNESSEE (17-5, 7-3 SEC) 2017-18 » SCHEDULE & RECORD at #24/#24 KENTUCKY (17-6, 6-4 SEC) OVERALL RECORD: 17-5 FEB. 6 » RUPP ARENA » LEXINGTON, KY. » 7:01 PM ET SEC 7-3 NON-CONFERENCE 10-2 THE MATCHUP HOME 10-2 AWAY 5-2 TENNESSEE VOLUNTEERS KENTUCKY WILDCATS vs NEUTRAL 2-1 THE RECORD QUICK COMPARISON 77.8 ppg Points Per Game 76.8 ppg THE SCHEDULE 67.0 ppg Points Allowed Per Game 73.0 ppg DATE OPPONENT (TV) TIME/RESULT 36.7 rpg Rebounding Per Game 39.1 rpg N10 Presbyterian (SEC Network+) W, 88-53 34.4 rpg Rebounding Defense 34.0 rpg N14 High Point (SEC Network+) W, 84-53 N22 1-vs. #18 Purdue (ESPN2) W, 78-75 (OT) .453 Field Goal Pct. .468 N23 1-vs. #5 Villanova (ESPN) L, 85-76 .398 3-Point Pct. .335 UTSPORTS.COM UKATHLETICS.COM N24 1- vs. NC State (ESPN2) W, 67-58 N29 Mercer (SEC Network+) W, 84-60 TENNESSEE QUICK FACTS KENTUCKY QUICK FACTS Head Coach: Rick Barnes (Lenoir-Rhyne, 1977) Head Coach: John Calipari (Clarion State, 1982) D3 at Georgia Tech (ESPNU) W, 77-70 Record at Tennessee: 48-40 / 3rd year Record at Kentucky: 266-59 / 9th year D9 Lispcomb (SEC Network) W, 81-71 D17 #7 North Carolina (ESPN) L 78-73 Career Record: 652-354 / 31st year Career Record: 669-197 / 26th year D20 Furman (SEC Network) W, 66-61 Scoring Leader: Grant Williams (16.2 ppg, 7th in SEC) Scoring Leader: Kevin Knox (15.1 ppg, 12th in SEC) D23 at Wake Forest (ESPN2) W, 79-60 Rebounds Leader: Admiral Schofield (6.3 rpg, T-12th in SEC) Rebounds Leaders: K. -

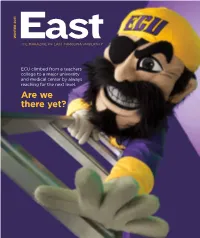

Are We There Yet? Viewfinder

winter 2011 EastThe Magazine of easT Carolina UniversiTy eCU climbed from a teachers college to a major university and medical center by always reaching for the next level. Are we there yet? viewfinder PirAtes HAve Hooks who needs a sword or an eye patch when you can show Pirate pride with the finger hook? the Boneyard student section in the new horseshoe at Dowdy-Ficklen stadium was full of hooks at Homecoming. winter 2011 EastThe Magazine of easT Carolina UniversiTy FeAtUres are we There yeT? 18 It’s been a long climb for East Carolina,By Mary Schulken the scrappy ’79 little teachers college that fought epic battles to become a major university and medical center. Have we arrived? And if so, how do we know? sToCKing The PanTRY 18 2 8 Just two years out of college, SamBy Steve Wornom Tuttle ’90 co-founded The Pantry chain of convenience stores and grew it into nearly 500 28 locations. In the second act of a stellar business career, he’s again proving he can spot business opportunities that satisfy consumer appetite. EASING The oUCh 3 2 Cecelia Valrie ’99 is identifying newBy Marion ways Blackburnto help sick children feel less pain and lead more normal lives. The UMPire of eligibiliTy 36 Tim Metcalf, who’s responsible for keepingBy J. Eric ECUEckard out of trouble with the NCAA, relies on a 484-page book of rules. And the rules change every year. DePArtMENTS 32 froM oUr readers ..................3 36 The eCU rePorT . 4 winTer arTs CALENDAR . 16 froM The CLASSROOM . 32 PiraTe naTion . -

Karns High School

KARNS HIGH SCHOOL FRESHMAN PARENT ORIENTATION MARCH 2, 2017 ADMINISTRATION KHS Administration- –Principal- Brad Corum –Assistant Principals- Laicee Hatfield and Spencer Long –Freshmen Dean- Dedra Hall Core Subject Number of Credits Diploma English 4 Math 4 Requirements Science 3 World History / 1 • Students will need a Geography minimum number US History 1 of 28 credits to graduate. US Government 0.5 Economics 0.5 • Every course attempted will Phys. Ed & Health 1.5 count towards GPA Personal Finance 0.5 Elective Focus 3 World Language 2 Fine Arts 1 Total 28 Elective Focus Clusters • Math/Science • Career And Technical • Humanities/World Education Language – Teaching as a Profession • Fine Arts – Diagnostic Services – Nursing Services • Intervention/Academic – Therapeutic Services • Advanced Placement – Engineering or Dual Enrollment – Banking & Finance • JROTC – Accounting – Office Management • Physical Education – Business Management • AVID – Marketing Management • Human Services – Culinary Arts Elective Focus Clusters Offered at Byington Solway • Welding • Structural Systems • Mechanical, Electrical, & Plumbing • Audio/Visual Production • Early Childhood Education • Cosmetology • Law Enforcement Services • Legal & Correction Services • Fire Management Services • Diesel Math/Science & Engineering • Any combination of three Math and/or Science electives in addition to the required math and science courses. Humanities (World Languages) Any combination of courses in ELA, World Languages (above Level 2), and Social Studies, above the core requirements. • Spanish • Latin • French • German “…the more years of language, the better-it shows that the student has gone beyond the minimum requirement.”-Lisa Brassord, Assistant Director of Admissions, Smith College JROTC Physical Fitness Advanced Placement / Dual Enrollment • Any combination of three of the same type course (i.e. -

KAREN BALNICKI WETHERALL, MS, RDN, LDN, FAND 120 Graceland Rd

KAREN BALNICKI WETHERALL, MS, RDN, LDN, FAND 120 Graceland Rd. Oak Ridge, TN 37830 (h) 865-220-9002 (c) 865-466-7002 email: [email protected] EDUCATION BOSTON UNIVERSITY, MS, Nutrition Education Boston, MA Masters Thesis Proposal: "Nutrition Education in Medical Schools" BETH ISRAEL HOSPITAL, Dietetic Internship Boston, MA MARYMOUNT COLLEGE, BS, Human Nutrition and Foods (of Fordam University) Tarrytown & Bronx, NY EXPERIENCE The University of Tennessee (UT) Knoxville, TN Knoxville, TN 1995-Present Director, Dietetic Internship • Direct and coordinate dietetic internship experiences; contracting services with local hospitals and health care facilities to provide quality and comprehensive hands-on clinical/work experiences for dietetic interns. • Advise, direct, and evaluate dietetic interns’ needs and progress through weekly communications and evaluations. • Responsible for maintaining University’s accreditation of the internship with Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics (ACEND) of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND). • Market program to prospective students and coordinate annual intern selection. 1994-Present Senior Lecturer (promoted from Lecturer to Senior Lecturer 2013) • Nutrition 422: Nutrition Counseling. A skills-based course designed for students to become familiar with effective client-centered counseling for behavioral & lifestyle change (2019-present) • Nutrition 490: Clinical Internship. Clinical course associated with the Dietetic Internship; a problem-based, case studies course designed to bridge didactic with clinical experiences. (1995-present) • Nutrition 410: Professional Issues in Dietetics. An interactive class designed to create discussion on hot topics in the dietetics profession. (2005-present) • Nutrition 201: Careers in Nutrition. Provides students the opportunity to envision themselves in nutrition jobs through guest speakers who present on nutrition research, sports, wellness, community and clinical nutrition. -

Walk-To-School Prioritization Analysis for the Schools of Knox County, Tennessee

Walk-To-School Prioritization Analysis for the schools of Knox County, Tennessee Prepared for the Knox County Dept. of Engineering & Public Works by January 2014 The objective of this study is to identify the locations in Knox County having the greatest amount of potential and realized pedestrian activity associated with the walk-to-school trip type. With knowl- edge about where the greatest pedestrian demand exists, capital planners can focus efforts toward the determination of specific pedestrian infrastructure needs across the county. The Knox County school walking trip estimates were developed using RPM’s non-motorized trip modeling process. The process uses a combination of local and national data to produce walk-to- school trip estimates for all 86 public schools in Knox County. In the model, every student repre- sents one trip made to school, with the potential for this to be a walking trip increasing as the trip length decreases. The student’s home address is geo-coded as his/her origin and the student’s school is geo-coded as his/her destination. The student data was obtained from Knox County Schools for all 59,276 students in the school system using school year 2013-2014 enrollment data. With the origin and destination of all travel-to-school trips mapped, a unique trip assignment for all 59,276 trips to school was performed using current open-source mapping. This process results in the travel-to-school distance assuming that the existing street network is used to make the trip. Interstates and other ...have an average pedestrian-prohibited ...and a median Students who live within.. -

Seeking Recovery Under the Tennessee

PAGE APB The Knoxville Focus June 21, 2021 June 21, 2021 www.knoxfocus.com ONLINE AUCTIONPAGE A1 June 25, 2021 The Knoxville See photos at The Knoxville fountaincityauction.com Fountain City Auction (865)474-9931 OCUS FREETake One! www.knoxfocus.com F June 21, 2021 Phone: 865-686-9970 | PO Box 18377, Knoxville, TN 37928 | Located at 4109 Central Avenue Pike, Knoxville, Tennessee 37912 Tax break for Andrew Johnson Building OKed by city council By Mike Steely Senior Writer party consultant recommends pandemic but there’s no fund- [email protected] the deal. Welch said the city’s ing available to the developer The Knoxville City Council decision is based on the cost of for those. He said the short- approved of a tax break for similar projects. term micro-apartments being BNA Associates LLC for the Councilwoman Amelia Parker planned will be converted to purchase of the historic Andrew said that other financing has hotel rooms. Johnson Building Tuesday eve- not been pursued and asked Councilwoman Seema Singh ning but not without several why the city had to take part questioned the use of public questions. The 7-2 approval of in a county-owned property. funding and said the project the 12-year PILOT (Payment-In- Councilwoman Janet Tester- should look at private fund- Lieu-of-Taxes) saw much dis- man said the building would ing. Welch said “there is a risk” cussion. have 143 hotel rooms after and said BNA will be paying The Austin-East soccer team and coach Jonathan Netherland were honored Councilwoman Lynne Fugate five years. -

Knoxville-Knox County Park, Recreation and Greenways Plan

The Knoxville-Knox County Park, Recreation and Greenways Plan As Amended through November 2011 (See the List of Amendments of the back of this page.) Adopted by: The Knoxville-Knox County Metropolitan Planning Commission on December 10, 2009 The Knox County Commission on January 25, 2010 The Knoxville City Council on January 26, 2010, and amended on January 25, 2011 Prepared by the Metropolitan Planning Commission for the Knoxville Parks and Recreation Department and the Knox County Parks and Recreation Department Prepared for: The City of Knoxville, Tennessee, Bill Haslam, Mayor Knox County, Tennessee, Mike Ragsdale, Mayor List of Amendments: April 2011: This plan was amended by the adoption of the Inskip Small Area Plan. Additions were made to pages 39-40 and the map on page 22 was updated. November 2011: This plan was amended by the adoption of the South City Sector Plan. The text on page 42 was changed to match the sector plan text and the maps on pages 22 and 43 were updated. Table of Contents Mission Statements ....................................................................................... 5 Maps Concepts: A Framework for the Plan ........................................................... 21 I. Introduction .............................................................................................. 7 Countywide Existing and Proposed Greenways ........................................... 22 II. Park Types, Inventory and Assessment of Parks and Recreation Central City Sector..................................................................................... -

Farragut Teacher in Running for State Teacher of the Year

April 15, 2013 www.knoxfocus.com INSIDEPAGE A1 April 15, 2013 FREE- Take One! Farragut teacher in running FOCUS Weekly Poll* In your opinion, should for state Teacher of the Year individual personal The Tennessee Department of in-service trainings – most recently and/or technology. information regarding Education recently announced Knox on Numeracy for the Common Core. She is among 27 regional finalists County School teacher Wanda Lacy Her community involvement is also selected for the statewide competi- handgun carry permits has been selected as a Centers of significant. She integrates ways to tion. The pool of regional finalists will be public information Regional Excellence Finalist for the assist The Love Kitchen and Second be narrowed to nine, then one final- or kept private? 2013-2014 Tennessee Teacher of Harvest Food Bank into her class- ist will be chosen to represent each the Year competition. es. Her 2007 class holds the school of the three grand divisions of the PUBLIC Wanda Lacy, who was recently record by collecting 13,539 cans of state and The Tennessee Teacher of awarded as the Knox County Schools’ food for Second Harvest. the Year will be selected from those 41.25% High School Teacher of the Year, has She founded the Farragut High three finalists. been with Knox County Schools for Math Academy where she works The final winner will represent PRIVATE thirty years and currently teaches with students and their mentors Tennessee in the National Teacher at Farragut High School where she from community organizations such of the Year competition and is an teaches AP Calculus. -

Table of Contents • Usc Aiken Quick Facts Media

TABLE OF CONTENTS • USC AIKEN QUICK FACTS MEDIA INFORMATION SUPPORT STAFF Asst. Sports Information Director: Brendan Roberston Quick Facts .......................................1 Volleyball Support Staff ...................... 5 Alma Mater/Year: USCA, 2009 Email: [email protected] SPONSORS INDEX THE UNIVERSITY Office Phone: 803-641-3252 Fairfield Inn & Suites ........................... 5 Administration • Athletic Staff ...........2 Office Fax: 803-641-3759 Holiday Inn Express ............................ 5 Internet Site: www.PacerSports.com Dr. Tom Hallman, Chancellor .............3 Midland Valley Country Club .............. 9 Randy Warrick, AD ............................3 Quality Inn & Suites ............................ 9 Athletic Administration ......................4 Media Information .............................6 CREDITS History of USC Aiken .........................7 GENERAL INFORMATION Convocation Center ...................... 6-7 Written, Compiled, and Designed Location: 471 University Parkway Milledge Austin and Brian Hand Aiken, S.C. 29801 COACHING STAFF Editor Founded/Enrollment: 1961/3,250 Brian Hand Head Coach Glenn Cox ..................12 Nickname: Lady Pacers Assistant Editors Colors: Cardinal, Navy, and White Milledge Austin; Brendan Robert- THE OUTLOOK National Affiliation: NCAA Div. II son; Glenn Cox Conference: Peach Belt Cover Design Season Preview ...............................13 Arena: Convocation Center (3,600) Jeff Mastromonico Preseason PBC Poll ........................13 First Year of NCAA Volleyball: