Dream-Machines.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Джоð½ Зоñ€Ð½ ÐлÐ

Джон Зорн ÐÐ »Ð±ÑƒÐ¼ ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (Ð ´Ð¸ÑÐ ºÐ¾Ð³Ñ€Ð°Ñ„иÑÑ ‚а & график) The Big Gundown https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-big-gundown-849633/songs Spy vs Spy https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/spy-vs-spy-249882/songs Buck Jam Tonic https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/buck-jam-tonic-2927453/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/six-litanies-for-heliogabalus- Six Litanies for Heliogabalus 3485596/songs Late Works https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/late-works-3218450/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/templars%3A-in-sacred-blood- Templars: In Sacred Blood 3493947/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/moonchild%3A-songs-without-words- Moonchild: Songs Without Words 3323574/songs The Crucible https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-crucible-966286/songs Ipsissimus https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/ipsissimus-3154239/songs The Concealed https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-concealed-1825565/songs Spillane https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/spillane-847460/songs Mount Analogue https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/mount-analogue-3326006/songs Locus Solus https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/locus-solus-3257777/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/at-the-gates-of-paradise- At the Gates of Paradise 2868730/songs Ganryu Island https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/ganryu-island-3095196/songs The Mysteries https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-mysteries-15077054/songs A Vision in Blakelight -

Ted Nelson History of Computing

History of Computing Douglas R. Dechow Daniele C. Struppa Editors Intertwingled The Work and Influence of Ted Nelson History of Computing Founding Editor Martin Campbell-Kelly, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK Series Editor Gerard Alberts, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Advisory Board Jack Copeland, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand Ulf Hashagen, Deutsches Museum, Munich, Germany John V. Tucker, Swansea University, Swansea, UK Jeffrey R. Yost, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA The History of Computing series publishes high-quality books which address the history of computing, with an emphasis on the ‘externalist’ view of this history, more accessible to a wider audience. The series examines content and history from four main quadrants: the history of relevant technologies, the history of the core science, the history of relevant business and economic developments, and the history of computing as it pertains to social history and societal developments. Titles can span a variety of product types, including but not exclusively, themed volumes, biographies, ‘profi le’ books (with brief biographies of a number of key people), expansions of workshop proceedings, general readers, scholarly expositions, titles used as ancillary textbooks, revivals and new editions of previous worthy titles. These books will appeal, varyingly, to academics and students in computer science, history, mathematics, business and technology studies. Some titles will also directly appeal to professionals and practitioners -

The Book of Lies Falsely :So Called

LIBER CCCXXXIII THE BOOK OF LIES FALSELY :SO CALLED (c) Ordo Templi Orientis. First published London: E.J. Wieland, 1913. Second edition with commentary Ilfracombe: Haydn Press, 1952 This electronic edition created by Celephaïs Press somewhere beyond the Tanarian Hills Original key entry by Frater E.A.D.N. Formatting and some further proof reading by Frater T.S. THE BOOK OF LIES WHICH IS ALSO FALSELY CALLED BREAKS THE WANDERINGS OR FALSIFICATIONS OF THE ONE THOUGHT OF FRATER PERDURABO (Aleister Crowley) WHICH THOUGHT IS ITSELF UNTRUE A REPRINT with an additional commentary to each chapter. “Break, break, break At the foot of thy stones, O Sea ! And I would that I could utter The thoughts that arise in me! COMMENTARY (Title Page) The number of the book is 333, as implying dis-persion, so as to correspond with the title, “Breaks” and “Lies”. However, the “one thought is itself untrue”, and therefore its falsifications are relatively true. This book therefore consists of statements as nearly true as is possible to human language. The verse from Tennyson is inserted partly because of the pun on the word “break”; partly because of the reference to the meaning of this title page, as explained above; partly because it is intensely amusing for Crowley to quote Tennyson. There is no joke or subtle meaning in the publisher’s imprint. V A\A\ Publication in Class C and D Official for the Grade of Babe of the Abyss ? ! KEFALH H OUK ESTI KEFALH O!1 THE ANTE PRIMAL TRIAD WHICH IS NOT-GOD Nothing is. -

Ijiji '!!.=~:;~~~~"!:~~~!:T:I' LIFE Amer, Mosl Wanted Amel Mo.St Wanted Amel Most Wanled Amer

SA McCreary County Record, Tuessday, Apri124, 2012, Whitley City, Kentucky Saturday Evening April 28, 2012 .;11!1•• ;111•• 1'!'.... 113'!1. I I .111!1· ... ·f·I'II._t'..IICII- WATE/ABC The Blind Side Local TV GUIDE WVLTA:lSS NCIS The Mentalist 48 Hours Mystery Local WBIRINBC Escape Routes The Firm Law & Order: SVU Local Saturday Night Live WDKYIF0X... NASCAR Racing Aleafraz New Girl ILocal April 25 - May 1 AIl,E Storage IStorage Storage IStorage Flipped Oft Flipping Bosto.n Storage IStorage A~e Braveheart Braveheart CMT Road House Texas Women Southern Nights Texas Women Southern Nights CNN. CNN Presents Piers Mo.rgan To.night CNN Newsro.om CNN Presents 24/7 Mayweather e , , II ;; .. , , , , II II DISC Secret Service Killing bin Laden Seal Team 6 Auction Auction Seal Team 6 'MorJ F~m IApt. 23 Ravenga Loc;)I Nlgl:illl~a Jimmy Kimmel uve DISN Austin [Josslu Phineas IAustin Austin Austin Austin Jessie Jessie [Josslu IIfIIl'r1Oa5 Sul'liwr: One Wo~d CrimI 00I Min d~ :CSt C,lme 800110 Local: la10 Sh Ow Loll.IIl'IIm 'llalG WSIRINBC 8<lny Ie.FF E! Legally Blonde Kate·Will lce-Coc« The Soup Chelsea Fashio.n Po.lice WOK V/FOX Am eilc9.n idOl local ESPN NBA Basketball NBA BasKetball ESPN2 Ouarterback Year/Ouarterback Baseball Tonight SportsCenter SportsCenter SI..-a gil ISlora (/Cl lSI ora go IDug DuC!<D. Duel( D. DUel( D, IDuCKD, Siurage 'ISlorag1l FAM />JIIC Norm Counlry Pirates·Dea d Alice in Wonderland Finding Neverland CMf E> treme-Homs 'Ilea ventura At;(! Ventura FoX Dear John Dear John l.oule ILo.uie CNN Anderson Coiltler %0 Pllirs Morgan Tonlgl,t AndGf~O" Coiltler 360 E. -

SCMS 2019 Conference Program

CELEBRATING SIXTY YEARS SCMS 1959-2019 SCMSCONFERENCE 2019PROGRAM Sheraton Grand Seattle MARCH 13–17 Letter from the President Dear 2019 Conference Attendees, This year marks the 60th anniversary of the Society for Cinema and Media Studies. Formed in 1959, the first national meeting of what was then called the Society of Cinematologists was held at the New York University Faculty Club in April 1960. The two-day national meeting consisted of a business meeting where they discussed their hope to have a journal; a panel on sources, with a discussion of “off-beat films” and the problem of renters returning mutilated copies of Battleship Potemkin; and a luncheon, including Erwin Panofsky, Parker Tyler, Dwight MacDonald and Siegfried Kracauer among the 29 people present. What a start! The Society has grown tremendously since that first meeting. We changed our name to the Society for Cinema Studies in 1969, and then added Media to become SCMS in 2002. From 29 people at the first meeting, we now have approximately 3000 members in 38 nations. The conference has 423 panels, roundtables and workshops and 23 seminars across five-days. In 1960, total expenses for the society were listed as $71.32. Now, they are over $800,000 annually. And our journal, first established in 1961, then renamed Cinema Journal in 1966, was renamed again in October 2018 to become JCMS: The Journal of Cinema and Media Studies. This conference shows the range and breadth of what is now considered “cinematology,” with panels and awards on diverse topics that encompass game studies, podcasts, animation, reality TV, sports media, contemporary film, and early cinema; and approaches that include affect studies, eco-criticism, archival research, critical race studies, and queer theory, among others. -

Abraham's Uncircumcised Children

ABRAHAM’S UNCIRCUMCISED CHILDREN: THE ENOCHIC PRECEDENT FOR PAUL’S PARADOXICAL CLAIM IN GALATIANS 3:29 by Amy Genevive Dibley A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union in Near Easter Religions in the Graduate Division of the University of California at Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor LeAnn Snow Flesher, Chair Professor Daniel Boyarin Professor Eugene Eung-Chun Park Professor Yair Zakovitch Professor Erich S. Gruen Fall 2013 ABSTRACT Abraham’s Uncircumcised Children: The Enochic Precedent for Paul’s Paradoxical Claim in Galatians 3:29 by Amy Genevive Dibley Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union in Near Easter Religions in the Graduate Division University of California, Berkeley Professor LeAnn Snow Flesher, Chair This study proposes the Book of Dreams as the precedent for Paul’s program of gentile reclamation qua gentiles predating the composition of the Epistles by two centuries. 1 Dedication To my husband Peter, for whom the words loving and supportive and partnership hardly begin to encompass the richness of our journey together through this process. For our girls, Langsea and Lucia (5 and 4 years old as I submit this), who when playing “mommy” pause from dressing and feeding baby dolls to write their own dissertations. In thanks to the women of First Covenant Church in Rockford, Illinois and Kerry Staurseth (Langsea’s godmother) who watched those most precious to me so that this first child could at last be born, proving that it also takes a village to write a dissertation. -

Kabbalah, Magic & the Great Work of Self Transformation

KABBALAH, MAGIC AHD THE GREAT WORK Of SELf-TRAHSfORMATIOH A COMPL€T€ COURS€ LYAM THOMAS CHRISTOPHER Llewellyn Publications Woodbury, Minnesota Contents Acknowledgments Vl1 one Though Only a Few Will Rise 1 two The First Steps 15 three The Secret Lineage 35 four Neophyte 57 five That Darkly Splendid World 89 SIX The Mind Born of Matter 129 seven The Liquid Intelligence 175 eight Fuel for the Fire 227 ntne The Portal 267 ten The Work of the Adept 315 Appendix A: The Consecration ofthe Adeptus Wand 331 Appendix B: Suggested Forms ofExercise 345 Endnotes 353 Works Cited 359 Index 363 Acknowledgments The first challenge to appear before the new student of magic is the overwhehning amount of published material from which he must prepare a road map of self-initiation. Without guidance, this is usually impossible. Therefore, lowe my biggest thanks to Peter and Laura Yorke of Ra Horakhty Temple, who provided my first exposure to self-initiation techniques in the Golden Dawn. Their years of expe rience with the Golden Dawn material yielded a structure of carefully selected ex ercises, which their students still use today to bring about a gradual transformation. WIthout such well-prescribed use of the Golden Dawn's techniques, it would have been difficult to make progress in its grade system. The basic structure of the course in this book is built on a foundation of the Golden Dawn's elemental grade system as my teachers passed it on. In particular, it develops further their choice to use the color correspondences of the Four Worlds, a piece of the original Golden Dawn system that very few occultists have recognized as an ini tiatory tool. -

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List # 20 Wild Westerns: Marshals & Gunman 2 Days in the Valley (2 Discs) 2 Family Movies: Family Time: Adventures 24 Season 1 (7 Discs) of Gallant Bess & The Pied Piper of 24 Season 2 (7 Discs) Hamelin 24 Season 3 (7 Discs) 3:10 to Yuma 24 Season 4 (7 Discs) 30 Minutes or Less 24 Season 5 (7 Discs) 300 24 Season 6 (7 Discs) 3-Way 24 Season 7 (6 Discs) 4 Cult Horror Movies (2 Discs) 24 Season 8 (6 Discs) 4 Film Favorites: The Matrix Collection- 24: Redemption 2 Discs (4 Discs) 27 Dresses 4 Movies With Soul 40 Year Old Virgin, The 400 Years of the Telescope 50 Icons of Comedy 5 Action Movies 150 Cartoon Classics (4 Discs) 5 Great Movies Rated G 1917 5th Wave, The 1961 U.S. Figure Skating Championships 6 Family Movies (2 Discs) 8 Family Movies (2 Discs) A 8 Mile A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2 Discs) 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family A.R.C.H.I.E. 10 Minute Solution: Pilates Abandon 10 Movie Adventure Pack (2 Discs) Abduction 10,000 BC About Schmidt 102 Minutes That Changed America Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter 10th Kingdom, The (3 Discs) Absolute Power 11:14 Accountant, The 12 Angry Men Act of Valor 12 Years a Slave Action Films (2 Discs) 13 Ghosts of Scooby-Doo, The: The Action Pack Volume 6 complete series (2 Discs) Addams Family, The 13 Hours Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter 13 Towns of Huron County, The: A 150 Year Brother, The Heritage Adventures in Babysitting 16 Blocks Adventures in Zambezia 17th Annual Lane Automotive Car Show Adventures of Dally & Spanky 2005 Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland, The 20 Movie Star Films Adventures of Huck Finn, The Hartford Public Library DVD Title List Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. -

Marching for Healthy Babies

WEEKEND EDITION FRIDAY, APRIL 13 & SATURDAY, APRIL 14, 2012 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | 75¢ Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM Hair- raising efforts Loveloud A Wellborn-based United Way’s alternative rock/group, local impact Loveloud is the final per- formance in this season’s totals $1,075,973. FGC Entertainment series. The group, most recently By TONY BRITT seen on the Warped Tour, [email protected] perform on April 14th at Florida Gateway College. For more information or Few, if any men, want to for tickets, call (386) 754- lose most of their hair at 4340 or visit www.fgcenter- one time. tainment.com. But if losing his hair, in a public meeting, with a Toxic roundup pair of pink hair clippers, in front of close to 100 people The Columbia County meant the United Way of Toxic Roundup will be Suwannee Valley met its Saturday, April 14 at challenge goal, then Mike the Columbia County McKee, United Way presi- Fairgrounds from 9 a.m. dent took the buzz cut as a to 3 p.m. Safely dispose of COURTESY PHOTO good sport. your household hazard- Kaylie Spradley at 8 and a half months old in a photo taken Jan. 12. United Way of Suwannee ous wastes, including old Valley held its 2012 Royal paint, used oil, pesticides Awards Banquet and annual and insecticides. The meeting Thursday night at process is quick, easy Florida Gateway College and free of charge to Howard Conference Center, residents. There is a small Marching for chronicling the organiza- fee for businesses. Help keep our environment HAIR continued on 7A safe! For information call Columbia County landfill Healthy Babies at (386)752-6050. -

Ivan's Final Dissertation

Copyright by Ivan Angus Wolfe 2009 The Dissertation Committee for Ivan Angus Wolfe certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Arguing In Utopia: Edward Bellamy, Nineteenth Century Utopian Fiction, and American Rhetorical Culture Committee: Jeffrey Walker, Supervisor Mark Longaker Martin Kevorkian Trish Roberts-Miller Janet Davis Gregory Clark Arguing In Utopia: Edward Bellamy, Nineteenth Century Utopian Fiction, and American Rhetorical Culture by Ivan Angus Wolfe, A.A.S.; B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of English The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2009 Dedication To Alexandra Acknowledgements I would like to thank my entire dissertation committee for their invaluable feedback during every step of my writing process. Jeffrey Walker was an invaluable director, always making time for my questions and responding with feedback to my chapters in a timely manner. Martin Kevorkian, Mark Longaker, Janet Davis, and Trish Roberts-Miller all also gave excellent advice and made themselves available whenever I needed them. Gregory Clark not only provided the initial impetus for my interest in this area, but graciously joined the committee despite his numerous commitments. Most graduate students would feel blessed to have such a conscientious and careful committee. I would also like to thank my wife, Alexandra, for her help. She has likely read this dissertation more times than anyone but me. Elizabeth Cullingford also deserves special thanks for being an excellent English department chair and making me feel welcome my first semester at UT as her Teaching Assistant for E316K. -

Appendix a Software Environment for Plant Modeling

Appendix A Software environment for plant modeling This book is illustrated with images of plants which exist only as math- ematical models visualized by means of computer graphics. The soft- ware environment used to construct and experiment with these models includes dozens of programs and hundreds of data files. This creates the nontrivial problem of organizing all components for easy definition, saving, retrieval and modification of the models. In order to solve it, the idea of simulation was extended beyond the level of individual plants to an entire laboratory in botany [98]. Thus, a user can create and conduct experiments in a virtual laboratory by applying intuitive con- cepts and techniques from the “real” world. As an operating system defines the way a user perceives a computing environment, the virtual laboratory determines a user’s perception of the environment in which simulated experiments take place. In the future, a virtual laboratory may complement, extend, or even replace books as a means for gather- ing and presenting scientific information. Because of this potential, the laboratory in which the research reported in this book was produced is describedhereinmoredetail. A.1 A virtual laboratory in botany A virtual laboratory, like its “real” counterpart, is a playground for ex- User’s perimentation. It comes with a set of objects pertinent to its scientific perspective domain (in this case, plant models), tools which operate on these ob- jects, a reference book and a notebook. Once the concepts and tools are understood, the user can expand the laboratory by adding new objects, creating new experiments, and recording descriptions in the notebook. -

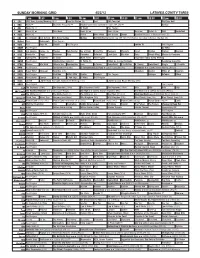

Sunday Morning Grid 4/22/12 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/22/12 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid PGA Tour Golf PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Hockey Conference Quarterfinal: Teams TBA. (N) Å Hockey 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Å News (N) Å News Å Vista L.A. NBA Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Prince Mike Webb Joel Osteen Shook Baseball Dodgers at Houston Astros. (N) 11 FOX D. Jeremiah Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup: STP 400. From Kansas Speedway in Kansas City, Kan. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Tomorrow’s Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Hope Hr. Church Paid Program Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program 22 Niños 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Paint This Dewberry Wyland’s Sara’s Kitchen Kitchen Mexican 28 KCET Hands On Raggs Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Land/Lost Hey Kids Taste Simply Ming Moyers & Company 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Paid Program Inspiration Today Camp Meeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Muchachitas Como Tú Al Punto (N) Fútbol de la Liga Mexicana República Deportiva 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley From Heart King Is J. Franklin 46 KFTR Paid Program Toonturama Presenta El Campamento de Papá › (2007, Comedia) (PG) Blankman ›› (1994) Damon Wayans.