Is There a Public Access Right to Academic Libraries in the United States and Canada?*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

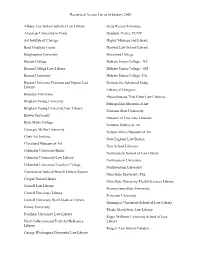

Reciprocal Access List As of January 2020 Albany Law School Schaffer

Reciprocal Access List as of January 2020 Albany Law School Schaffer Law Library Getty Research Institute American University in Cairo Graduate Center, CUNY Art Institute of Chicago Hagley Museum and Library Bard Graduate Center Harvard Law School Library Binghamton University Haverford College Boston College Hebrew Union College - NY Boston College Law Library Hebrew Union College - OH Boston University Hebrew Union College -CA Boston University Fineman and Pappas Law Institute for Advanced Study Library Library of Congress Brandeis University Massachusetts Trial Court Law Libraries Brigham Young University Metropolitan Museum of Art Brigham Young University Law Library Montana State University Brown University Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Bryn Mawr College National Gallery of Art Carnegie Mellon University Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Clark Art Institute New England Law Boston Cleveland Museum of Art New School Libraries Columbia University-Butler Northeastern School of Law Library Columbia University-Law Library Northeastern University Columbia University-Teachers College Northwestern University Connecticut Judicial Branch Library System Ohio State University, The Cooper Union Library Ohio State University-Health Sciences Library Cornell Law Library Pennsylvania State University Cornell University Library Princeton University Cornell University Weill Medical Library Quinnipiac University School of Law Library Emory University Rhode Island State Law Library Fordham University Law Library Roger Williams University School of Law Frick -

Annual Report of the Executive Committee of the Capital Project and Space Allocation Committee (Caps) Presentation to Planning and Budget Committee

Annual Report of the Executive Committee of the Capital Project and Space Allocation Committee (CaPS) Presentation to Planning and Budget Committee Thursday May 6, 2021 Introduction Governing Council Approval Track Summary of Project Approvals: January – December 2020 CaPS Committee Highlighted Projects CaPS Executive Committee Highlighted Projects 2 CaPS CaPS Planning & Budget Academic University Business Board Governing Exec Board Affairs Board Council Projects Approval* < $5M On Consent On Consent In Camera Agenda, Concur Agenda, Approve Consider and For Review and Consider and with Confirmation by Projects Subject to Approve for information Recommend to VP Recommend to Recommendation Executive $5M-$20M Confirmation by the Execution, only and VP/Provost Academic Board** of Academic Committee Executive Approve if Board Committee financing required *** In Camera Consider and Consider and Consider and For Review and Concur with Projects Recommend to Consider and Approve for Consider and information Recommend to VP Recommendation >$20M Academic Board Recommend to GC Execution, Approve only and VP/Provost of Academic ** Approve if Board*** financing required *Committees at UTSC and UTM are responsible for campus specific approvals under $5M **Campus Affairs and Campus Councils at UTSC and UTM are responsible for considering and recommending campus specific projects, $5M and over, to Academic Board ***Capital Projects within its area of responsibility Consider = On the main meeting agenda for full detailed discussion Consent = Agenda items -

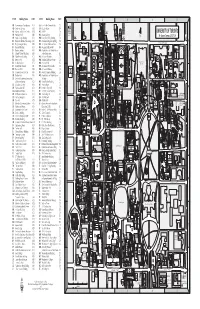

3D Map1103.Pdf

CODE Building Name GRID CODE Building Name GRID 1 2 3 4 5 AB Astronomy and Astrophysics (E5) LM Lash Miller Chemical Labs (D2) AD WR AD Enrolment Services (A2) LW Faculty of Law (B4) Institute of AH Alumni Hall, Muzzo Family (D5) M2 MARS 2 (F4) Child Study JH ST. GEORGE OI SK UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO 45 Walmer ROAD BEDFORD AN Annesley Hall (B4) MA Massey College (C2) Road BAY SPADINA ST. GEORGE N St. George Campus 2017-18 AP Anthropology Building (E2) MB Lassonde Mining Building (F3) ROAD SPADINA Tartu A A BA Bahen Ctr. for Info. Technology (E2) MC Mechanical Engineering Bldg (E3) BLOOR STREET WEST BC Birge-Carnegie Library (B4) ME 39 Queen's Park Cres. East (D4) BLOOR STREET WEST FE WO BF Bancroft Building (D1) MG Margaret Addison Hall (A4) CO MK BI Banting Institute (F4) MK Munk School of Global Affairs - Royal BL Claude T. Bissell Building (B2) at the Observatory (A2) VA Conservatory LI BN Clara Benson Building (C1) ML McLuhan Program (D5) WA of Music CS GO MG BR Brennan Hall (C5) MM Macdonald-Mowat House (D2) SULTAN STREET IR Royal Ontario BS St. Basil’s Church (C5) MO Morrison Hall (C2) SA Museum BT Isabel Bader Theatre (B4 MP McLennan Physical Labs (E2) VA K AN STREET S BW Burwash Hall (B4) MR McMurrich Building (E3) PAR FA IA MA K WW HO WASHINGTON AVENUE GE CA Campus Co-op Day Care (B1) MS Medical Sciences Building (E3) L . T . A T S CB Best Institute (F4) MU Munk School of Global Affairs - W EEN'S EEN'S GC CE Centre of Engineering Innovation at Trinity (C3) CHARLES STREET WEST QU & Entrepreneurship (E2) NB North Borden Building (E1) MUSEUM VP BC BT BW CG Canadiana Gallery (E3) NC New College (D1) S HURON STREET IS ’ B R B CH Convocation Hall (E3) NF Northrop Frye Hall (B4) IN E FH RJ H EJ SU P UB CM Student Commons (F2) NL C. -

Library Assoc Invite 2009 Broadbent.Indd

L Carole Moore, Chief Librarian, cordially invites you to a lunch & lecture by Alan Broadbent Tuesday, January 26, 2010 • 12:00 Robarts Library, nd Floor Group Study Area How Big Cities and Immigrants Make Canada Great A LAN BROADBENT is author of the book Urban Nation—Why We Need to Give Power to the Cities to Make Canada Strong, published by Harper Collins in 2008. Alan is Chairman and CEO of the Avana Capital Corporation, and Chairman of The Maytree Foundation. Avana initiates and funds civic engagement Space is limited; please reserve projects to strengthen the public discourse on civil society, including: the by calling 416-978-7644 or send Jane Jacobs Prize; the Institute for Municipal Finance and Governance at the email to [email protected]. Munk Centre, University of Toronto; and Ideas That Matter, an organization to convene discourse on progressive ideas concerning the public good. Alan is Please pay by credit card or by also Chairman of several related organizations, including the Caledon Institute mailing a cheque for $30, payable of Social Policy (co-founded by Maytree in 1992), Tamarack—An Institute for to University of Toronto, to: Community Engagement (co-founded in 2001), and Diaspora Dialogues, which supports the creation and presentation of new writing that refl ects the diversity Karen Turko, of Toronto. Director of Advancement Alan Broadbent is also Chairman of the Tides Canada Foundation; advisor to & Special Projects, the Literary Review of Canada; Co-Chair of Happy Planet Foods; Director of University of Toronto Libraries, Sustainalytics; Member of the Governors’ Council of the Toronto Public Library 130 St. -

Ludus Glawdiatorus

AUGUST 18TH – AUGUST 30TH O-WEEK GUIDE ludus gLAWdiatorus University of Toronto Faculty of Law 2014 Orientation Week 2 AUGUST 18TH – AUGUST 30TH O-WEEK GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS O-Week Contacts Page 3 Schedule Page 4 Map Page 8 Life at U of T Law Page 10 Sponsors Page 12 3 O-Week Contacts General Email: [email protected] 8 Website: www.glawdiators.com Twitter @gLAWdiators ( Co-Chairs: Jen Aziz: 647-529-9441 Grace Smith: 647-460-5903 Kellie Mildren: 416-949-3484 4 SCHEDULE – WEEK 1 5 SCHEDULE – WEEK 2 6 SCHEDULE DETAILS REGISTRATION MONDAY AUGUST 18: 8AM – 9AM BURWASH QUAD Come meet your fellow glawdiators, pick up your armour (t- shirts) and weapons (swag), and enjoy a light breakfast. FACULTY GREETING MONDAY AUGUST 18: 9AM – 10:30AM BURWASH QUAD Introduction by your faculty and the Students’ Law Society. GLAWDIATORIAL TRAINING MONDAY AUGUST 18: 10:30AM – 11:30AM BURWASH QUAD Team building challenges to get you acquainted with your table. E-ZONE THURSDAY AUGUST 21: 7:30PM – 11PM MEET YOUR CHARIOT (BUS) IN FRONT OF FALCONER A “corporate event venue”: i.e. laser tag, bumper cars, and the like. PUBLIC INTEREST LUNCH FRIDAY AUGUST 22: 12PM – 2PM BURWASH QUAD Meet the directors of the public interest programs at the faculty of law. There will also be a BBQ. INCLUSIVE LEARNING ENVIRONMENT FRIDAY AUGUST 22: 2PM – 4PM NORTHROP FRYE ROOM 003 A mandatory inclusivity training session hosted by the faculty and presented by Anita Balakrishna. GLAWDIATORIAL GAMES FRIDAY AUGUST 22: 4PM – 8PM MEET WITH YOUR TABLES IN BURWASH QUAD A series of challenges and activities (gladiator joust, tug of war and other games) for you to win points towards the Emperor’s Cup. -

2019.2020 Annual Report

annual report 2019/20 A MESSAGE FROM OUR UNIVERSITY CHIEF LIBRARIAN We had been preparing to release this report remote support, meeting the academic and Improving the student experience was also a in early spring when the COVID-19 pandemic research needs of our community from a safe key focus, with supports for mental health and emerged. Within a very short time frame, the distance during an unprecedented global health family life such as drop-in counselling during Province closed all but essential services and emergency. exams, meditation and prayer space, and child- we fully transitioned to online support for our care for student parents provided in library students and faculty. Although all of our library spaces in partnership with the University. As buildings were closed by March 24, our robust In Review part of our COVID-19 response, the Libraries online library never closed. The last year was characterized by a great deal hosted an online story time during which of collaboration across our extensive library U of T librarians read from their favourite Drawing upon a tremendous amount of system. Our entire community was deeply picture books. The Library also created a toolkit skill and dedication, staff immediately began engaged in projects with the potential to trans- of resources for families with children learning supporting remote courses and helping students form the way we work and provide service, from home to support educators, students and and faculty access electronic information from including the creation of a new Strategic Plan families adjusting to distance education. their homes. They partnered with faculty and and preparation for the launch of our new instructors to ensure our students’ academic Library Services Platform. -

Update KEEP@Downsview

Keep@Downsview Report for PAN ALA Annual Meeting, June 2019 Keep@Downsview is a partnership of the University of Toronto, the University of Ottawa, Western University, McMaster University, and Queen’s University. Our mandate is to preserve the scholarly record in Ontario in a shared high-density storage and preservation facility located at the University of Toronto’s Downsview Campus in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. This partnership is part of a larger movement, in Canadian higher education, to collaborate in developing shared print management strategies for long-term access to and preservation of scholarship and to share resources and costs. Recent Initiatives and Activities • The Partnership is represented on the newly-established Canadian Collective Print Preservation Strategy Working Group, which is jointly-sponsored by CARL (Canadian Association of Research Libraries) and LAC (Library & Archives Canada). The Working Group is following up on ideas identified at the 2017 @Risk North forum and will recommend avenues for potential national coordination of print collections. • Keep@Downsview members have been participating in the work of the Partnership for Shared Book Collections through membership on two of the Working Groups. • The members visited the ReCAP facility in October 2018 to learn more about metadata management and workflows in a large-scale operation and to explore ways we might collaborate. • To expand our capacity to improve access to our shared print collection, we are moving towards installing an Internet Archive scanning centre at the Downsview site, to complement the IA centre housed on the main campus of the University of Toronto. • The founding partner libraries are exploring the best strategy for expanding our membership in response to expressions of interest from other Canadian academic libraries. -

MUREX? Sesuak HE 009 235.- D 144 452 , 1, TITLE Perspectives Anaplans for Graduate Studies..19

MUREX? sEsuak HE 009 235.- D 144 452 , 1, TITLE Perspectives anaPlans for Graduate Studies..19, flu .ticai Sciences 1975. - ,,,, INSTITBTION : Ontario Co on Graduate Studies, Toronto. Academic Planning. Advisoty Comiitte 1)6 DATE 77,. 214p. OTE 1, AVAILABLE'FROM,', COuscil2of Ontario Universities, 30 St. e St., .. _ Suite 6039, Toronto, Ontario M5S 214 ($5.00, ch . payable to CeO.U. Holdings Ltd.). EDESPPIRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$11.3T Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Dootbral Pregramb:Employment Patterns;EmpfOyment 'Projectious; Enrollment Projections; *Foreign- CountrieS;'Graduate Students; *Graduate Study; Higher Education; Masters Degraes;'*Mathematics Curriculum; . *Mathematics Education; Needs4Assessment; 1 Persistence; *Statewide Planning; Universities IDENTIFItiS .*Ontario ABSTRACT 0: A planning study for graduate study inthe/ mathematical sciences in Ontario undertaken in1976-77.resUlted in some general and specific,- observationsakbut the Ontario universities. In eneral, graduate work in the mathematicalsciences is' of good-quality, and. most fields of mathematics arecompletely covered in One or anotheruniversity.; sole fields'are indentifie fot. ,further development. Enrollment projections are consideredto be in balance with the number ofgraduatis and job opportunities,although enrollment- to-graduati-gn ratios arelOw for doctoral students. It is recomirended thatthe;utiversities carefully watch enrollment /graduation data and the employment marketfor'changes..It, is alto 4elt,that part-time study be made available at thesister's vhdn feasible. -

News from the University of Toronto Libraries in THIS ISSUE Fall 2020

noteworthy Fall 2020 news from the university of toronto libraries IN THIS ISSUE Fall 2020 18 Windows on the world [ 3 ] Taking Note [ 11 ] Bringing Some Harmony to a Year of Discord [ 4 ] COVID-19 Collecting Community Experience Project [ 12 ] Information Literacy in an Era of Fake News [ 4 ] Once Upon a Time at the University of Toronto Libraries… [ 14 ] Jumping on the Bandwidth Wagon: Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library and University of Toronto Libraries Media Commons [ 5 ] Discrimination Not Allowed: Human Rights in Ontario, Archives Host Events Online 1962–2002 [ 17 ] Building on Your Support: The Lasting Power of Legacies, [ 6 ] Deepening Global Partnerships during the COVID-19 Pandemic Recognizing and Rewarding Undergraduate Student [ 8 ] The Other Pandemic of 2020 Researchers, and Robarts Common Construction [ 9 ] Demand and Supply: The Fisher Library in 2020 [ 19 ] Online Exhibitions [ 10 ] Open Access to Scientific Research: A Matter of Life and Death Cover image: Staying connected during times of separation — the University of Toronto Libraries online. Photo of person holding a tablet by Bjorn Antonissen via Unplash. Above: Keeping out the cold and letting in the light — the glass has been installed on the Robarts Common. Story on page 18. [ 2 ] TAKING NOTE noteworthy news from the university of toronto libraries EACH OF US HAS We know that the University Chief Librarian faced significant chal- novel coronavirus is not Larry P. Alford lenges over this past year. the only pandemic in our Editor Wherever this message midst; systemic racism, as Michael Cassabon finds you, I hope you and well as other forms of Designer your loved ones are as structural discrimination, Maureen Morin well and as whole as can are societal pandemics Contributing Writers be. -

Playtime at Robarts Library Opening a Family-Friendly Study Space at the University of Toronto

Jesse Carliner and Kyla Everall Playtime at Robarts Library Opening a family-friendly study space at the University of Toronto f academic libraries are sincere about their 24.4 hours for men.3 Given that the burden Icommitment to equity and inclusion, they of childcare primarily falls to women, lack must become more accessible for student of academic library support for parenting parents—a large and underserved population students disproportionately impacts women whose members may also have other margin- and has a negative effect on equitable access alized identities. Although accommodating to library resources and services, as well as children may seem to be outside the scope of overall learning and research opportunities. academic libraries’ mandate, if we are to fully At the University of Toronto, parenting stu- support research and learning on campus, we dents expressed that they have had to choose must try to reduce obstacles for parenting stu- their classes based on their childcare schedules dents however we can, including welcoming and the type of course work involved. Group their children into our libraries. To address this projects, for example, pose a challenge, be- need, the University of Toronto Libraries re- cause they may require students to arrange cently opened Canada’s first academic library additional childcare. Accessing services that family-friendly study space. are only available in person, such as consulta- tions with a librarian, can also be difficult to Parenting students in the United States arrange, due to the challenges and expense and Canada of finding childcare. In the United States, 4.8 million undergradu- ate students are raising children,1 and there What are libraries doing? is a trend among U.S. -

Tools and Technical Skills Languages Experience

GUITA LAMSECHI [email protected] Mobile: 416 821-7220 EDUCATION • Master of Information (Library & Information Systems Design), iSchool, University of Toronto • PhD, History of Art and Architecture, University of Toronto • Master of Arts, History of Art, University of Toronto • Bachelor of Education, I/S Computer Science, Visual Art, Communication Technologies, OISE • Bachelor of Arts (honours), University of Toronto TOOLS AND TECHNICAL SKILLS • Research Data Management & Visualization: Tableau, Gephi, Nvivo, MySQL, SQLlite, OpenRefine, R-Studio, Dataverse • Metadata standards and formats: MARC, MODS, DC, PREMIS, OAI-PMH, RDA, DOI, ORCID • Content Management Tools: Drupal, Islandora, Fedora; Samvera Hyku; Omeka; ArcGIS; AtoM; iiif; Dspace and more • Accessibility WCAG 2.0-2.1 Standards & Tools: JAWS, NVDA, WebAIM Color Contrast Checker, Wave, Achecker, Pa11y • Wireframing tools for app design and user testing: Figma, Balsamiq, Visio • Google Analytics & interpretation of results • Expert user of Adobe PhotoShop, Illustrator, InDesign, Acrobat Pro LANGUAGES Strong reading knowledge of German and French. Intermediate level oral and writing skills. EXPERIENCE LIBRARY TECHNOLOGIES AND DIGITAL PROJECTS User Experience and Accessibility Consultant • UI/UX Design Improvement, Testing, Accessible Communications for print, online, audio-visual media Clients: First Nations House and NCCT (healthcare app); Brav.io (mobile app); Workyard Labs | 2015 – 2019; 2021| Web Services & Digital Repository Analyst, Ontario Colleges Library Service -

Noteworthy Fall 2018.Indd

noteworthy Fall 2018 news from the university of toronto libraries IN THIS ISSUE Fall 2018 6 Dedicated Volunteers + Library Book Room = A Winning Combination [ 3 ] Taking Note [ 11 ] Richard Charles Lee Canada-Hong Kong Library Events [ 4 ] Fifteen Million and Counting: the 1481 Caxton Cicero [ 12 ] Cheng Yu Tung East Asian Library’s Highlights [ 5 ] Dedication of the Phi Kappa Pi, Sigma Pi Reading Room [ 13 ] Keep@Downsview Receives Outstanding Contribution Award [ 6 ] Information-Savvy Students Win Undergraduate Research Prizes [ 13 ] Healthy Indoors & Outside: Green Spaces & Mental Wellness Talk & Workshop [ 6 ] Robarts Library Book Room Volunteers Receive an Arbor Award [ 14 ] Bringing Virtual Worlds to Life at Gerstein + MADLab [ 7 ] Launch of the Chancellors’ Circle of Benefactors [ 15 ] Exhibitions & Events [ 8 ] Cookery, Forgery, Theory and Artistry: All at the Fisher Cover image: Dust jacket from the yellowback edition of Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1797–1851). Published by G. Routledge and Sons, London. 1882. Part of the De Monstris exhibition. Details on page 15. Above: Library Book Room volunteers receive their Arbor Awards. Story on page 6. [ 2 ] TAKING NOTE noteworthy news from the university of toronto libraries WELCOME TO THE FALL 2018 a daunting task. Artificial intelligence, Chief Librarian issue of Noteworthy. Recently I travelled to guided by expert librarians and archivists, Larry P. Alford China to visit a university library and may be part of the solution. Editor deliver a speech. I have had occasion previ- Recently, Neil Romanosky, Associate Jimmy Vuong ously to tour the libraries of Chinese Chief Librarian for Science Research & academic institutions, and this time I was Information, convened a UTL AI Interest Designer Maureen Morin struck by the growth and change since my Group to explore what the AI era will mean last visit.